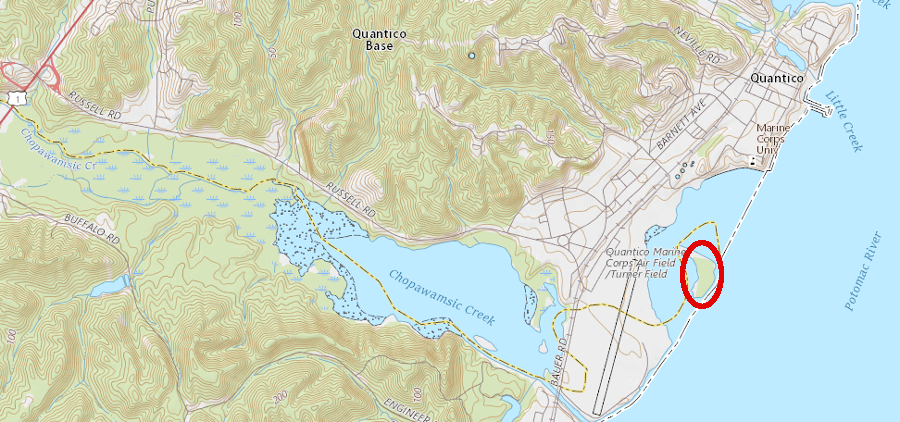

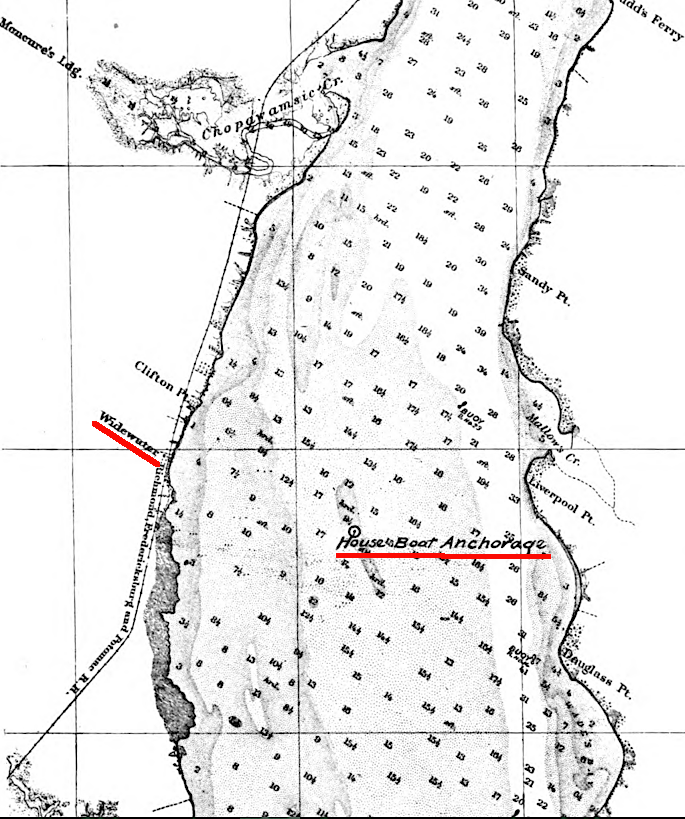

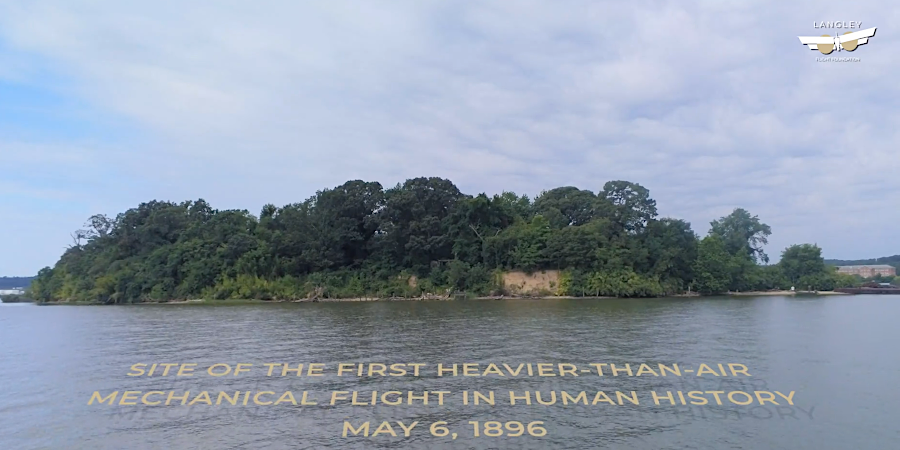

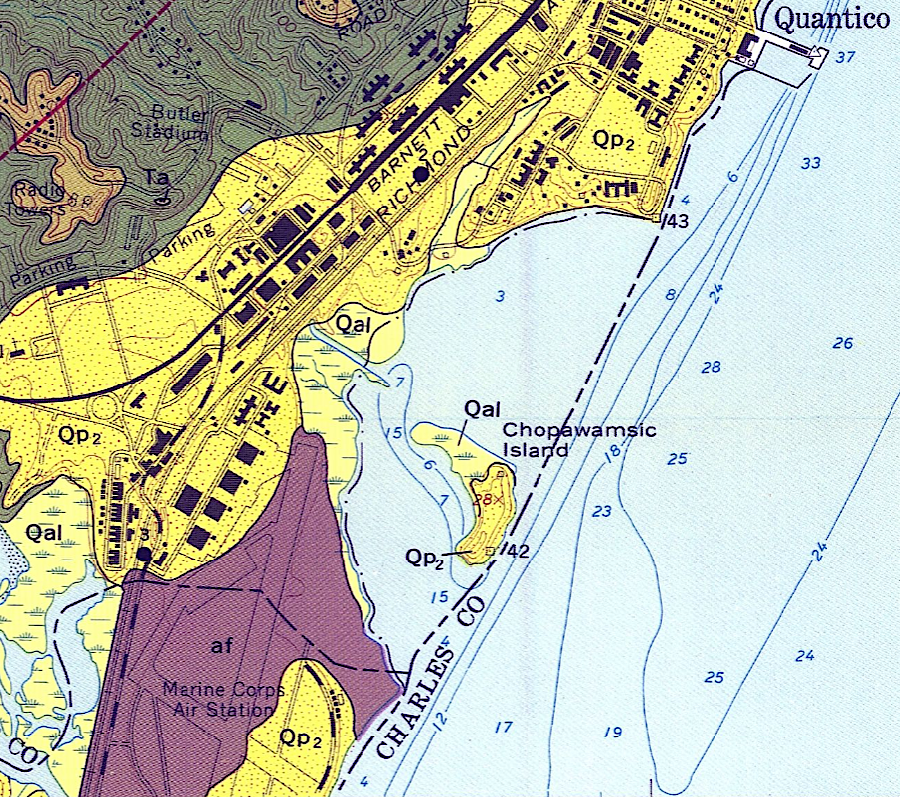

Samuel P. Langley, head of the Smithsonian, launched heavier-than-air aerodromes from a houseboat next to Chopawamsic Island until giving up in 1903

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Map Locator

Samuel P. Langley, head of the Smithsonian, launched heavier-than-air aerodromes from a houseboat next to Chopawamsic Island until giving up in 1903

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Map Locator

The first attempts at flying a heavier-than-air, engine-powered plane in Virginia were organized by Samuel P. Langley. He was Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, and obtained Federal government support for the project.

Langley constructed different versions of a plane, which he called an "aerodrome." He worked between 1893-1896 to launch an aerodrome powered by a steam engine. After succeeding, he returned to his duties at the Smithsonian.

Later, President McKinley expressed interest in advancing the capacity of airplanes to serve as war machines. Langley tried from 1898-1903 to create a plane with an internal combustion engine that could carry a pilot. That effort was funded by $50,000 from the War Department.

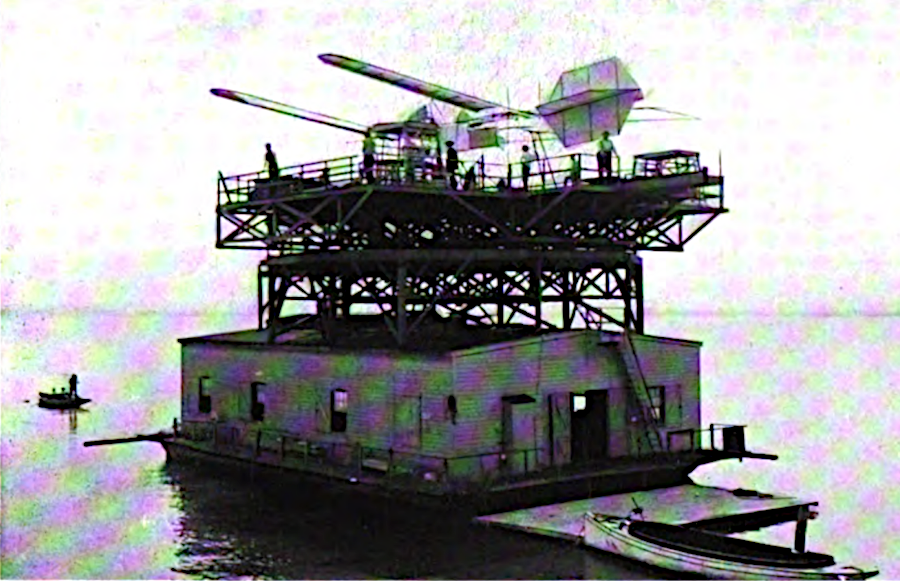

Langley recognized that his plane would need to land in water in order to minimize damage. He initially sought a launch site next to the Potomac River, but then developed an innovative solution:1

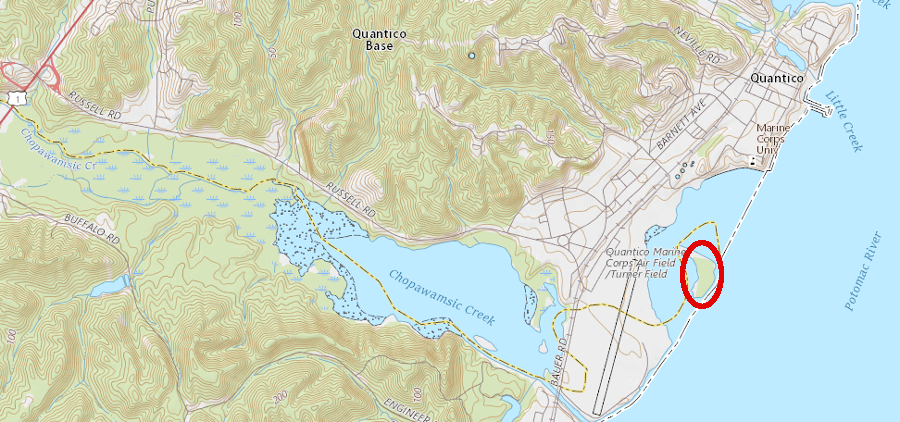

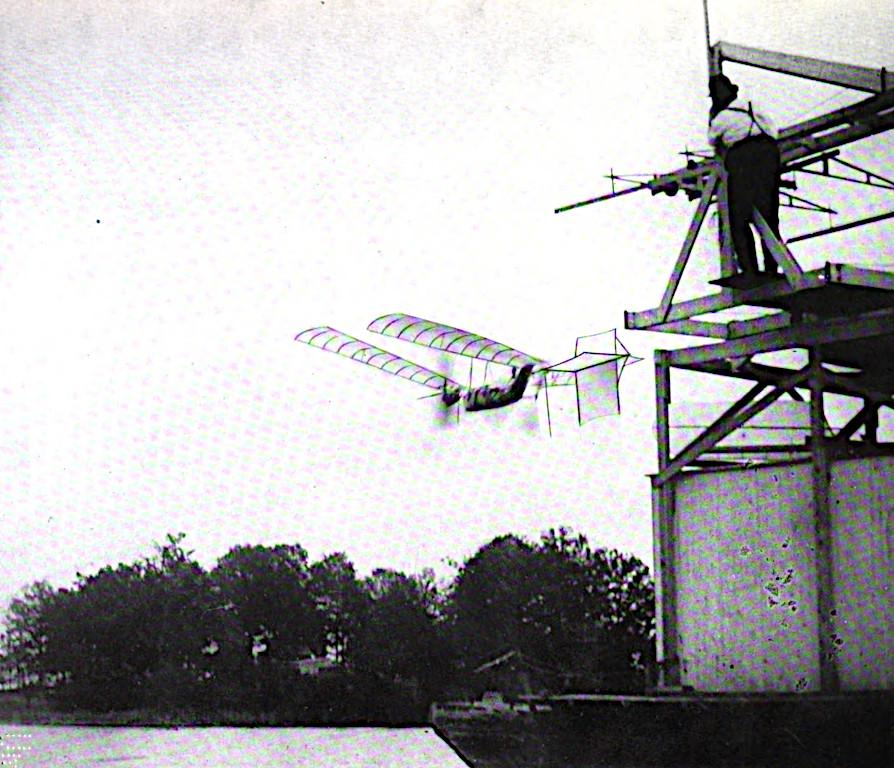

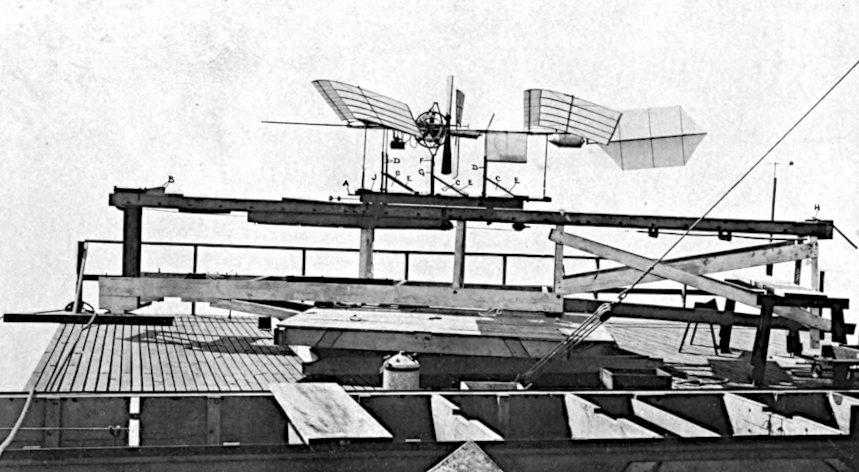

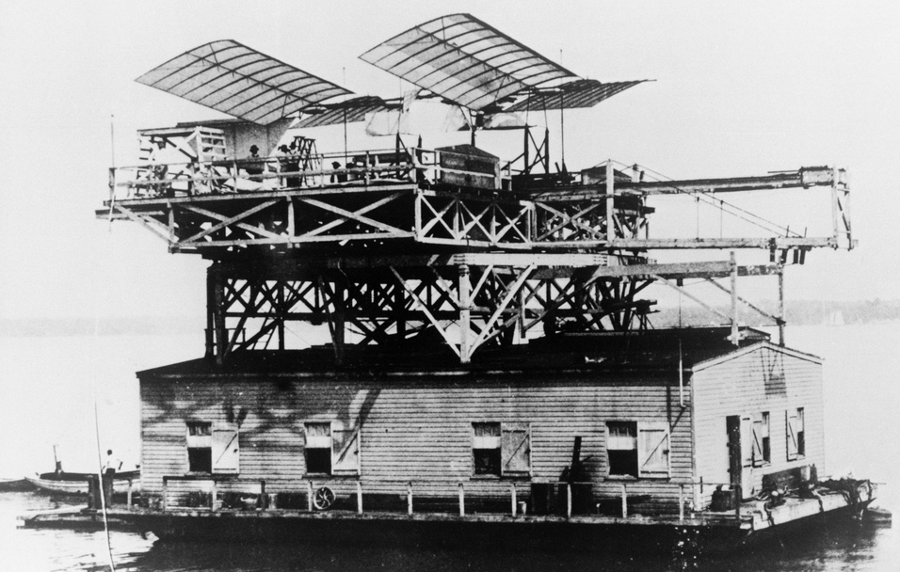

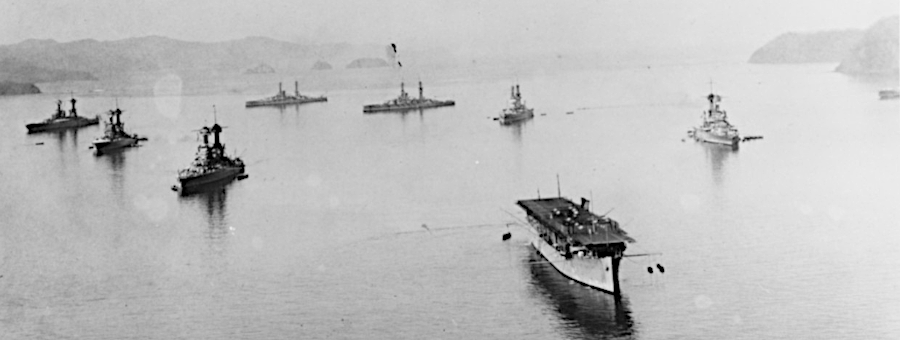

Langley modified a houseboat into the first aircraft carrier

Source: Samuel Pierpont Langley, Langley Memoir on Mechanical Flight, Part 1 (opposite p.106)

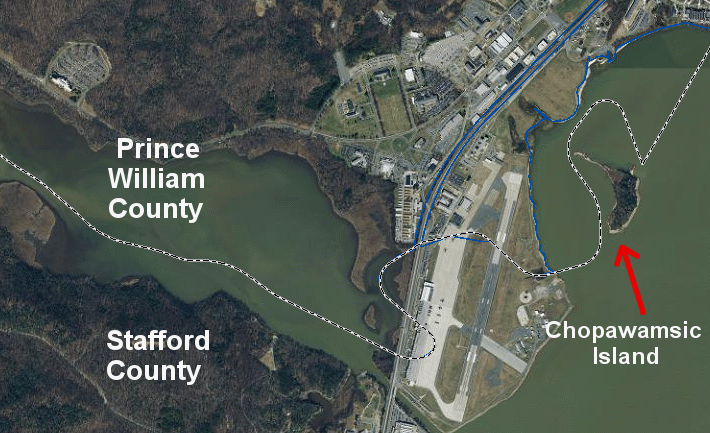

He located the houseboat next to Chopawamsic Island in the Potomac River, near the Quantico station of the railroad linking Washington and Richmond. The boat was 30 foot long and 12 foot wide. The "house" was built on the deck to store his aerodromes, and was not a shelter for people living on the boat:

According to Langley, his launches occurred from a portion of the Potomac River claimed by Virginia, since Chopawamsic Island was in Stafford County:2

Chopawamsic Island during the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, Map of n. eastern Virginia and vicinity of Washington ("McDowell Map," 1862)

The first attempt to launch Aerodrome Number 4 from the houseboat in 1893 was a complete failure. The plane was placed on one end of an inclined rod. The plan was to throw down the rod and provide a slight forward impulse to the plane as a spring pushed from the back. However, the slightest breeze made it impossible to keep the plane balanced on the end of the rod.

A second attempt was equally unsuccessful. While trying to balance the plane, fuel spilled from the engine and several times the plane caught on fire. On another attempt, the road broke and the plane fell directly into the boat. The aerodrome was never launched in 1893, despite eight attempts.

In 1894, the launch mechanism was redesigned. Langley later wrote that Aerodrome Number 5 was launched successfully, though his definition of success is questionable. The plane did separate successfully from the boat:3

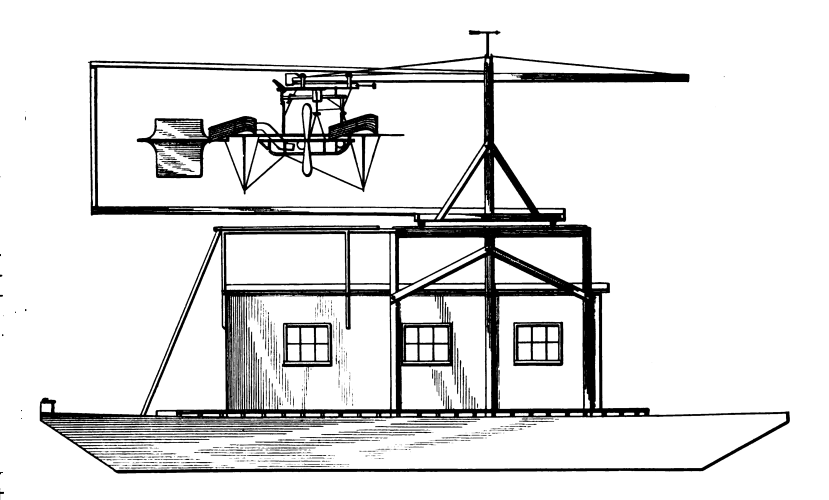

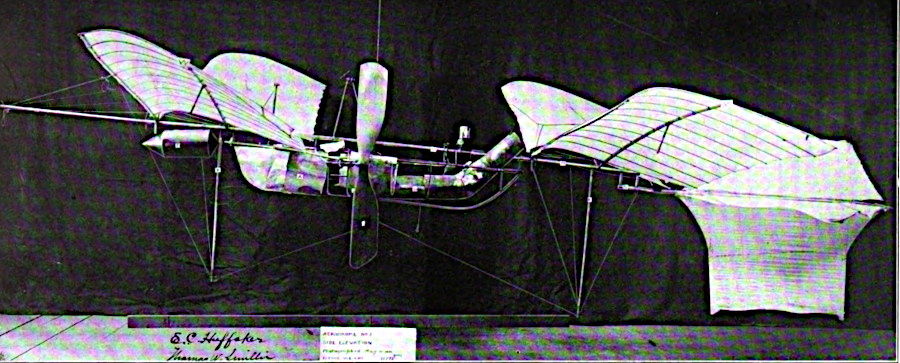

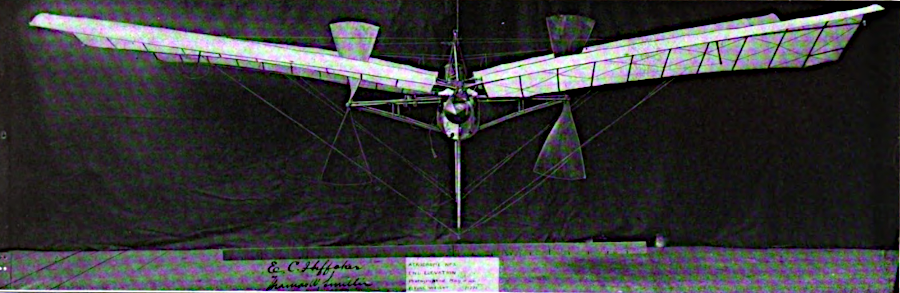

Langley's aerodromes were built around a frame of thin steel tubes

Source: Samuel Pierpont Langley, Langley Memoir on Mechanical Flight, Part 1 (opposite p.122)

On October 24, 1894, Aerodrome Number 4 traveled 130 feet in 4 seconds. Langley later described it as a "real, though brief, flight," and considered the launching device to have been perfected. Getting the 25-pound aircraft balanced as the plane moved through air became the focus of his attention; without a pilot on board the light aircraft, there was no way to restore equilibrium after launch.

He acknowledged that by the end of 1894:4

In 1895, Aerodrome Number 5 managed a flight lasting three seconds. After launch, it went forward 200 feet, descending smoothly the whole time until landing nose-down and damaging both propellers. Another flight lasting seven seconds ended because the engine ran out of fuel and water, after being held on the boat too long in order to build up steam pressure. Langley acknowledged that the flights were so short that "no actual flight had really been achieved."

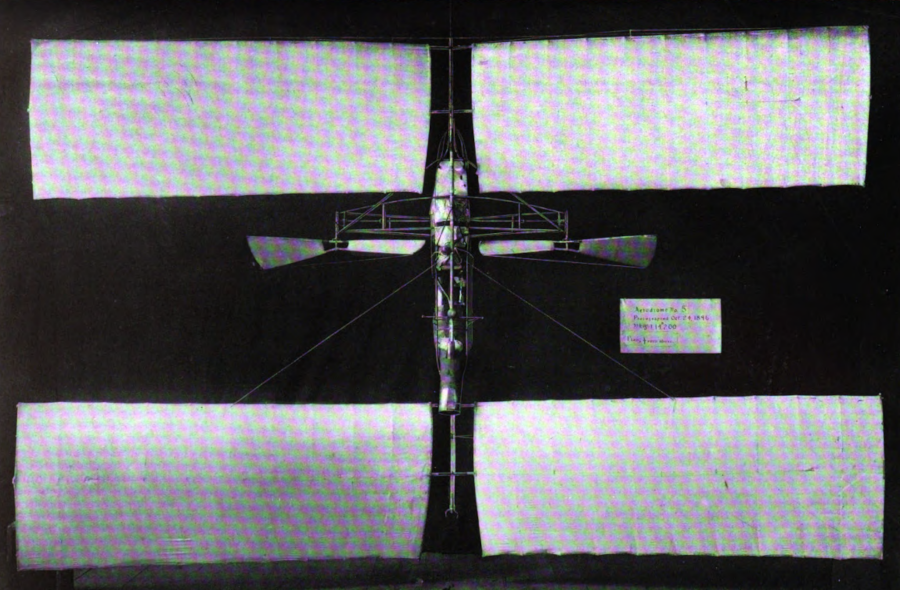

There were multiple challenges to identify and overcome. The steam engine did not provide sufficient power, and the wings flexed so much after launch that they did not provide the required lift. Af=t the end of 1895, Langley rebuilt his aerodromes to add a second pair of wings, to stiffen the wings, and to have the tail control just the direction of flight.

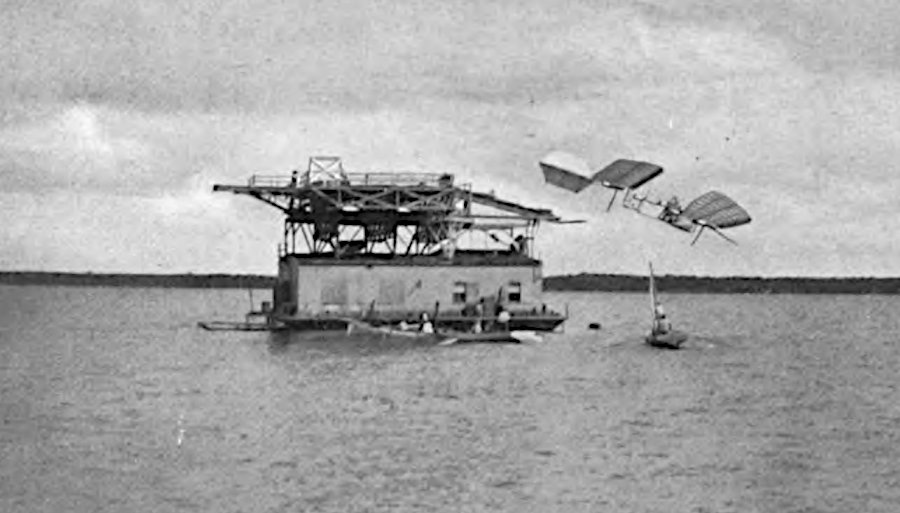

On May 6, 1896, Aerodrome Number 6 was launched from a spring-actuated catapult into a wind blowing 6-10 miles per hour. The left wing broke during the launch. The plane dropped off the houseboat and sank immediately in the river.

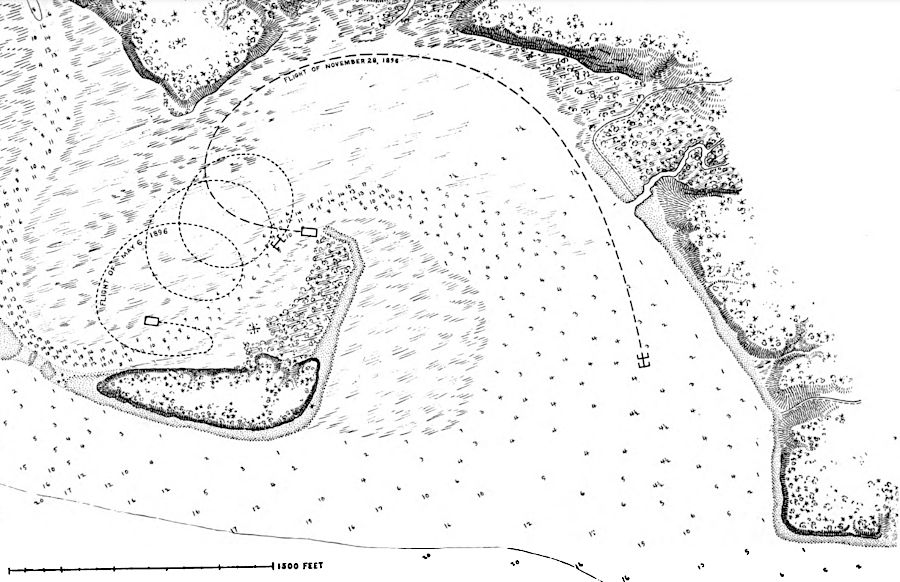

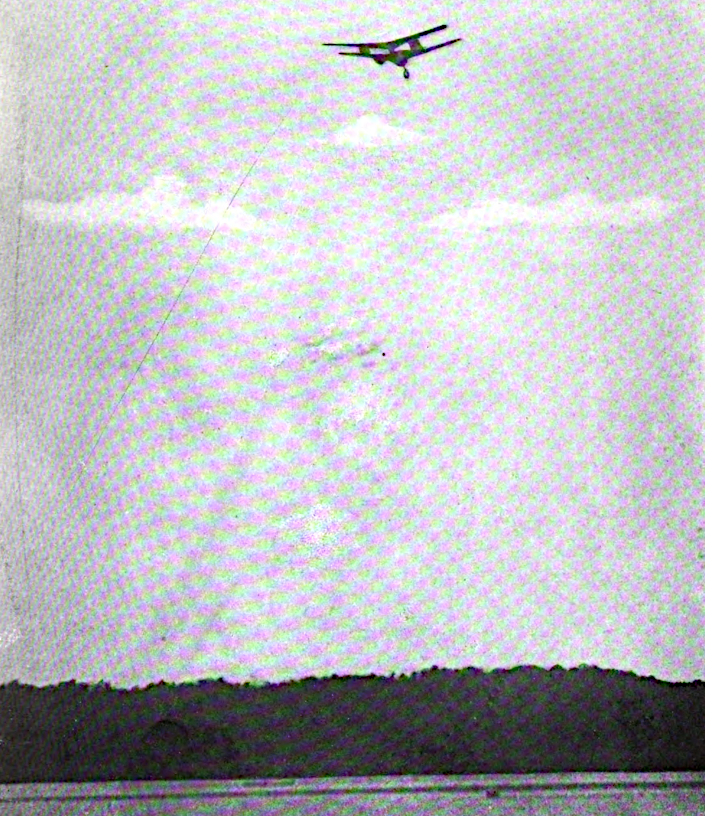

Aerodrome Number 5 was launched next from the modified houseboat. The heavier-than-air plane, with a framework of made of thin steel tubes, successfully flew twice, going 3,300 feet the first time and 2,300 feet the second time. Power was provided by a one-cylinder steam engine, and there was no pilot.

the first successful engine-powered airplane flight was on May 6, 1896, but did not have a pilot

Source: Samuel Pierpont Langley, Langley Memoir on Mechanical Flight, Part 1 (opposite p.108)

Langley described the first flight of an unpiloted, engine-driven, heavier-than-air plane:5

path of two aerodrome flights on May 6 and November 28, 1896 at Chopawamsic Island

Source: Samuel Pierpont Langley, Langley Memoir on Mechanical Flight, Part 1 (opposite p.108)

In the second successful flight on May 6, the plane reached a height of 60 feet. The plane flew in circles again:6

Aerodrome Number 5 flew up to 100 feet high on its first flight over the Potomac River on May 6, 1896

Source: Samuel Pierpont Langley, Langley Memoir on Mechanical Flight, Part 1 (opposite p.108)

On November 27, 1896, Aerodrome 6 flew again. It was in the air only six seconds and traveled just 100 yards that day. The next day, however, it flew a distance of 4,200 feet during one minute and forty-five seconds at a speed of 30 miles per hour.7

Aerodrome Number 6, looking from the side and tail, as repaired after the failed May 6, 1896 flight

Source: Samuel Pierpont Langley, Langley Memoir on Mechanical Flight, Part 1 (opposite p.116)

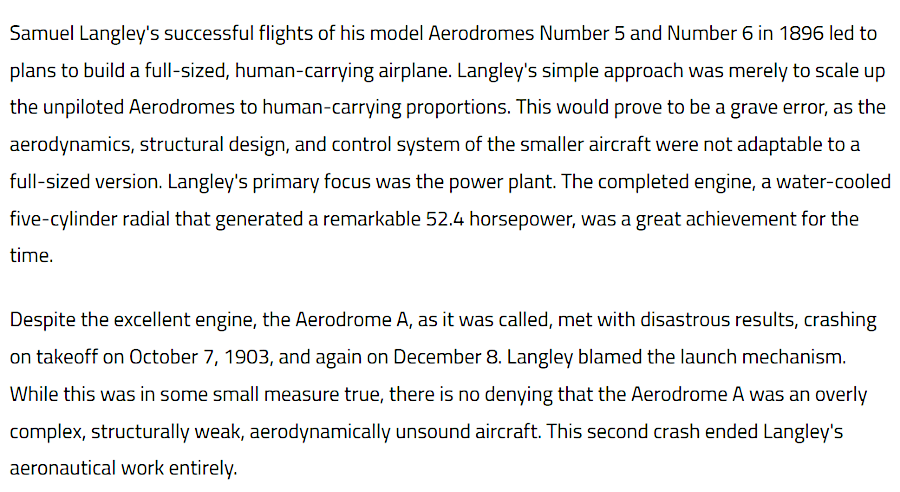

In 1898, Langley was recruited by President McKinley to create an airplane that could carry a human into the sky. McKinley was interested in the military advantages, and the regents of the Smithsonian Institution granted Langley the time to experiment.

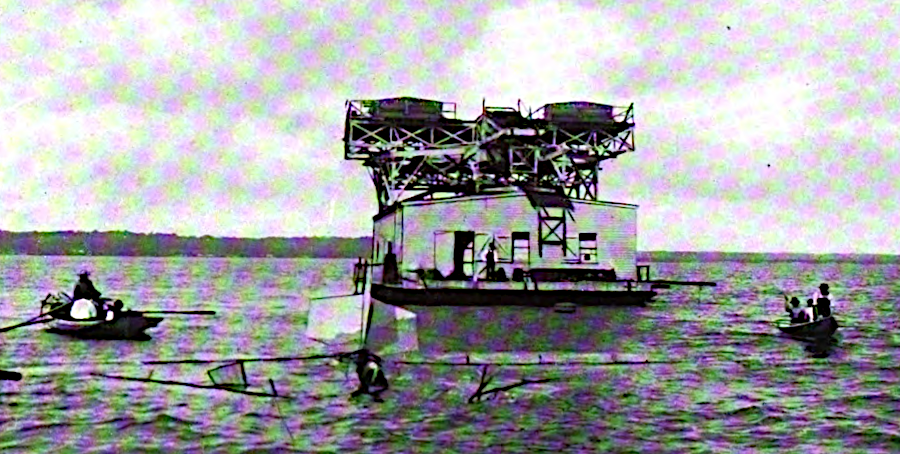

Langley planned to obtain an internal combustion engine weighing just 100 pounds that would provide 12 horse-power for turning propellers of his new design, Aerodrome A. The new plane had two 48-foot long wings, one wing in front of the pilot and one wing in the rear, and was 54 feet long. Langley also ordered construction of a new houseboat, this time 60 feet by 40 feet, with a special launching track on top.

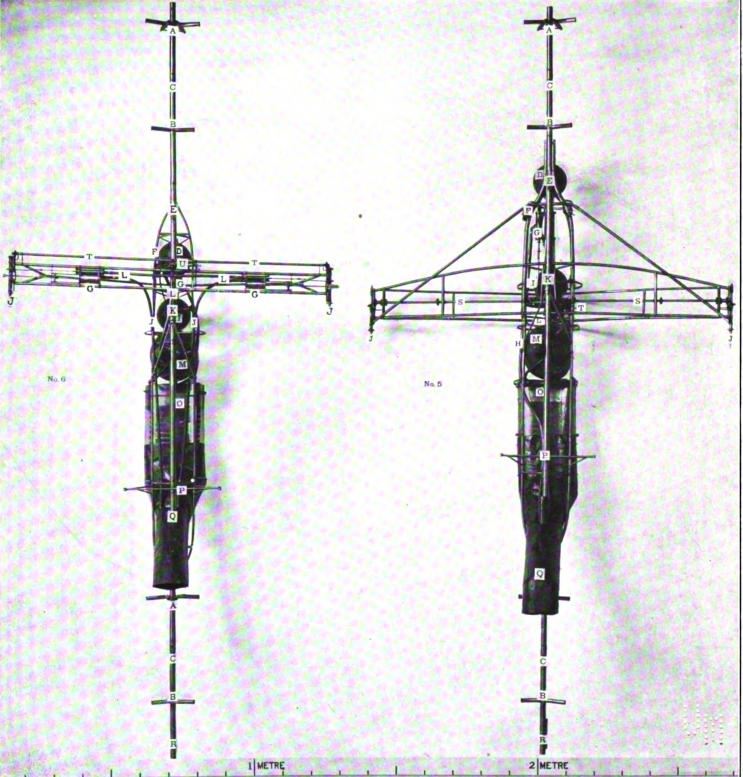

Langley's 1903 attempt to build a plane carrying a human pilot required a larger houseboat than his 1896 tests

Source: Charles M. Manley, Langley Memoir on Mechanical Flight, Part 2 (Plate 38)

The houseboat was towed down the Potomac River and moored off Stafford County's Widewater Peninsula in July, 1903. The eight workmen and a soldier detailed as a special guard traveled back and forth to Chopawamsic Island via a tugboat for meals.

in July 1903, when first testing a plane designed to carry a pilot, Langley located the new housboat opposite Widewater (downstream from Chopawamsic Island)

Source: Charles M. Manley, Langley Memoir on Mechanical Flight, Part 2 (Plate 85)

The initial experiments for a piloted plane involved steam-powered engines. Different models of aerodromes were launched from the houseboat off Chopawamsic Island until 1901. In 1903, Langley planned to test a quarter-sized model of the new Aerodrome A, using an internal combustion engine providing 50 horsepower and weighing just 120 pounds. However, the old houseboat had decayed, so the old launching superstructure was removed and placed on the new houseboat for the test.

a quarter-sized model was tested in 1903

Source: Charles M. Manley, Langley Memoir on Mechanical Flight, Part 2 (Plates 86, 92, 93)

After evaluating the tests of the quarter-sized model designed to carry a pilot, the next step was to test the full-sized plane known as Aerodrome A. Langley planned to place a dummy in the full-scale plane for its first test on October 7, 1903. However his assistant, Charles M. Manley, volunteered to be the pilot so a human could adjust the equilibrium of the plane after launch.

The first test was a failure. The plane's nose quickly turned down and the plane crashed 100 yards from the houseboat, so the value of a human pilot remained untested. Photography arranged for the test was helpful in identifying that mechanical parts for the launch apparatus had failed, rather than the wings or components on the frame.

As described by a Washington Star newspaper at the time, the experience:8

in the October 7, 1903 test, the full-sized plane with a pilot crashed right after launch

Source: Charles M. Manley, Langley Memoir on Mechanical Flight, Part 2 (Plate 95, Plate 99)

The houseboat with Aerodrome A was towed back to Washington DC. The $50,000 from the War Department had been spent by 1901; the Smithsonian Institution and private individuals had provided 100% of the funding for the experiments afterwards. To minimize costs, Langley decided to do the next test at the confluence of the Anacostia and Potomac rivers, close to where the houseboat was moored. He did not have the funding or the time to return to Chopawamsic Island or Widewater.

The last attempt at manned flight by Samuel Langley was on December 8, 1903. Weather was poor and chunks of ice were floating in the Potomac River, but the potential for a loss of further funding justified trying again despite the conditions.

The launch was finally conducted at 4:45pm, when it was so dark that almost all photography was useless. For unknown reasons, Aerodrome A's tail dragged onto the launching apparatus just before the plane flew into the air.

Samuel P. Langley last launched his aerodrome, once more unsuccessfully, from a modified houseboat at the confluence of the Anacostia and Potomac rivers on December 8, 1903

Source: NASA on The Commons, The Langley Aerodrome

The 60' long plane with 48' long wings, also known as "The Buzzard," hung briefly in a vertical position as the engine provided power. The plane then flipped backwards, with its top side closest to the Potomac River, and crashed into the water.

The Washington Star newspaper was not a cheerleader of Langley's efforts, and called the plane "Langley's Folly," The newspaper reported that at launch, the plane did an immediate half double somersault before falling into the Potomac River, ending up:9

on December 8, 1903, the launch mechanism failed again and Aerodrome A immediately crashed into the Potomac River

Source: Charles M. Manley, Langley Memoir on Mechanical Flight, Part 2 (Plate 101)

Charles M. Manley, Langley's assistant, was the pilot. He was lucky to escape being trapped underneath the plane as it sank, upside down. At the end of his difficult struggle to reach the surface, his head bumped into a block of ice that required maneuvering before getting his first breath.

Manley wrote later how Aerodrome A was totally wrecked not by the crash, but by the recovery:10

Nine days later on December 17, the Wright brothers successfully flew a heavier-than-air craft. Their plane, controlled by a human pilot, flew four times at Kill Devil Hills in North Carolina.

Samuel Langley had run out of money and lacked support to get new funding. On his own initiative, Manley obtained enough funding from private sources to repair the airframe. Langley never sought to pursue powered flight again.

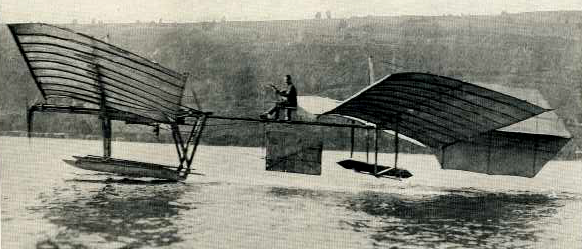

Langley died in 1906, but Aerodrome A did fly again. Charles Walcott replaced Langley as the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He funded a rival to the Wrights, Glenn Curtiss, who wanted to break the patents of the Wright brothers.

If Langley's plane had been capable of flight, and if the catapult had caused the failures during the 1903 attempts, then Walcott could argue that Aerodrome A demonstrated that the third Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution - rather than the Wright brothers - had developed the technology for shaping wings to achieve flight.

Actually getting Aerodrome A into the air would restore Langley's reputation, and a successful flight might trigger a court to rule that Langley's plane invalidated the Wright patents. With the support of Charles Walcott and the Smithsonian Institution, Curtiss borrowed Aerodrome A and altered Langley's plane. He added floats for taking off from water, rather than using Langley's spring-powered catapult, and made other modifications that improved flightworthiness. Curtiss flew the modified version successfully in 1914, taking off and landing at Lake Keuka in New York.11

Langley's aerodrome got into the air successfully only after Glenn Curtiss modified the engine and airframe, then added pontoons for taking off from Lake Keuka in 1914

Source: Smithsonian Institution, The First Man-Carrying Aeroplane Capable of Sustained Free Flight (plate 4)

Glenn Curtiss flew a modified version of Aerodrome A ("The Buzzard") in 1914

Source: New York Times (May 31, 2022)

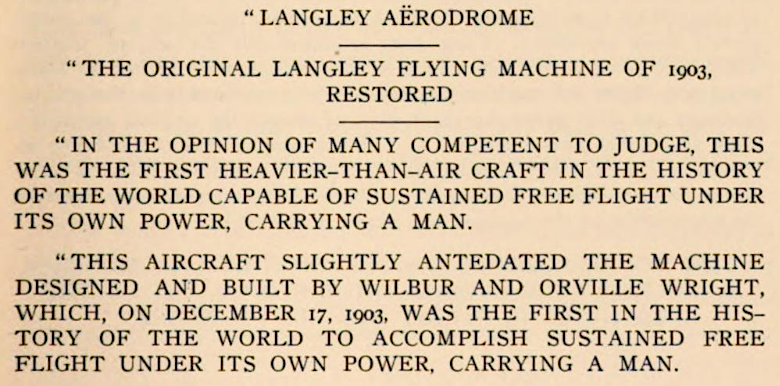

In the Smithsonian Institution buildings, Walcott ensured that Langley was portrayed as the inventor of the airplane. The Smithsonian restored and displayed Langley's aircraft starting in 1918. The museum's label boldly claimed Langley had accomplished a successful powered flight prior to the Wright brothers.12

the Smithsonian Institution claimed its former Secretary had created the first man-carrying aeroplane in the history of the world capable of sustained free flight

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society (Volume LXV, 1926, page 81)

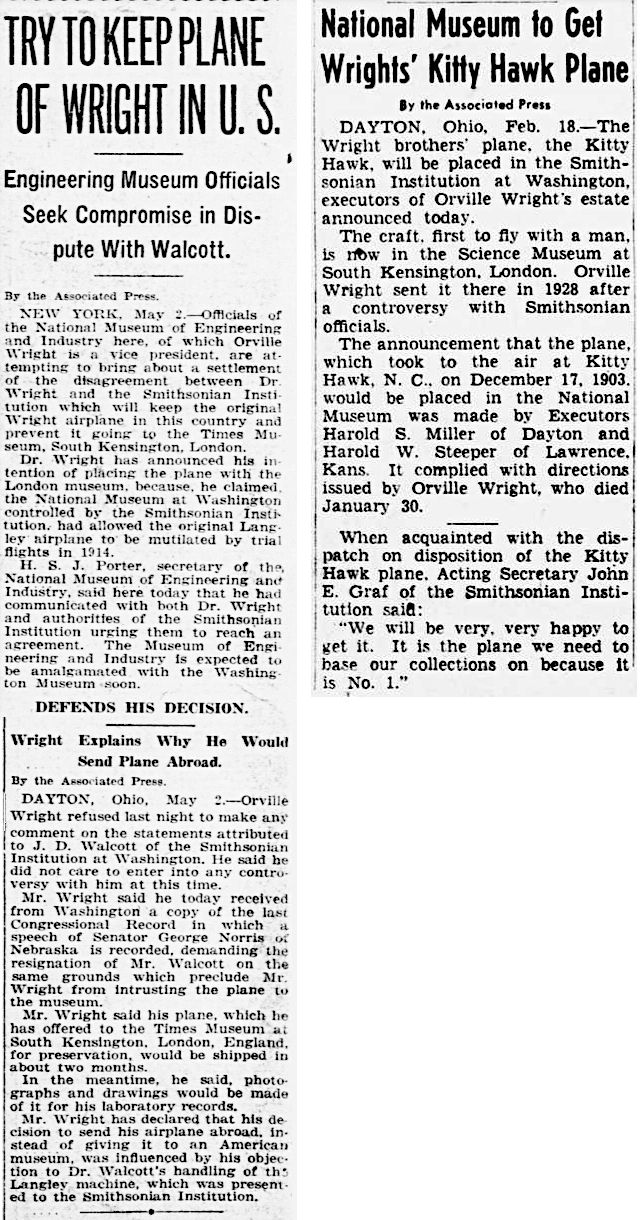

Orville Wright challenged that description in 1925, but the Smithsonian refused to retract its claim. In response to the misrepresentation of history, Orville Wright sent his 1903 Kitty Hawk Flyer to England for display and refused to donate it to the Smithsonian.

In 1942, the Smithsonian Institution finally acknowledged that Curtiss had modified Aerodrome A to make it flightworthy and dropped the claim that Samuel Langley was "first." That helped to smooth over the conflict with Orville Wright. He sold the plane to the Smithsonian and arranged to bring it back to the United States.

Included in the sale was this condition:13

The 1903 Kitty Hawk Flyer was put on display at the Smithsonian in 1948, with a card reading:14

the Smithsonian Institution website now emphasizes that Aerodrome A, which crashed on December 8, 1903, was an "aerodynamically unsound aircraft"

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Langley Aerodrome A

Aerodrome A is on exhibit now at the Udvar-Hazy Center of the Smithsonian Institution, near Dulles International Airport

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Langley Aerodrome A

If the 1914 claim that Samuel P. Langley built the "first man-carrying aeroplane in the history of the world capable of sustained free flight" had been true, then Chopawamsic Island (rather than Kill Devil Hills in North Carolina) might have become the home of a First in Flight Visitor Center managed by the National Park Service.

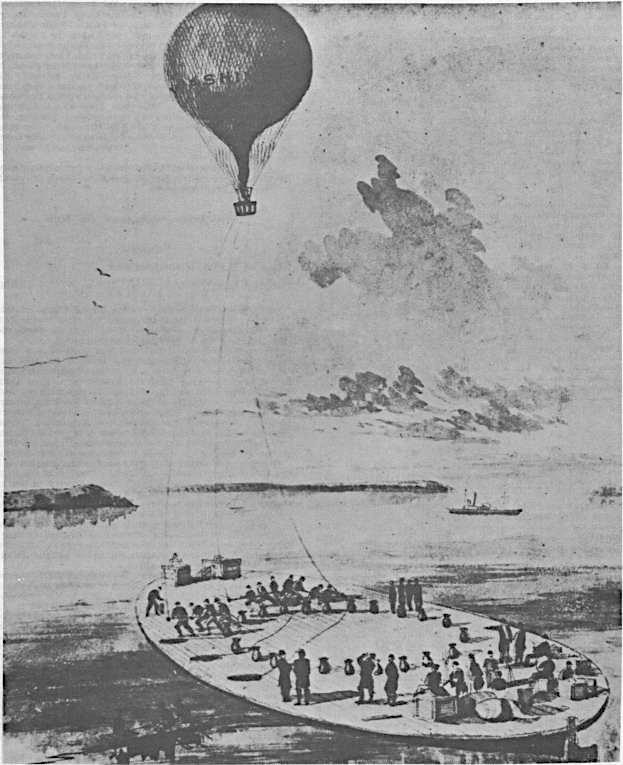

The exhibit might also have described Langley's houseboat in 1896 as the first aircraft carrier supporting planes with an engine. However, the houseboat was not the first aircraft carrier. That honor belongs to a modified coal barge, the George Washington Parke Custis. In 1861, the US Navy purchased it and added a gas-generating apparatus while based at the Washington Navy Yard. The barge was towed down the Potomac River to Mattawomen Creek.

On November 11, 1861, the balloon was inflated while the barge was near Mattawomen Creek. Thaddeus Lowe, General Daniel E. Sickles, and others climbed into the basket and were lifted up into the sky. Their aerial reconnaissance revealed the Confederate fortifications on the Virginia shoreline, three miles away. Lowe reported the next day:15

the first aircraft carrier was a converted coal barge used to launch a reconnaissance balloon on November 11, 1861

Source: Naval History and Heritage Command, George Washington Parke Custis

Lowe later had a tug pull the George Washington Parke Custis for 13 miles while he mapped Confederate fortifications from a height of 1,000 feet.

An even earlier flight had used a boat as the platform for launching an aerial reconnaissance balloon. A rival of Thaddeus Lowe, John LaMountain, had been recruited by Major General Benjamin F. Butler at Fort Monroe to help gather intelligence from a balloon. On August 3, 1861, LaMountain used the deck of the Fanny to fly a balloon 2,000 feet high over the James River. Later he used the Union tugboat Adriatic to tether his balloon.

The US Navy describes the George Washington Parke Custis as the first aircraft carrier.

The US Navy identifies the first launch of an airplane from a stationary ship as a flight on November 14, 1910 from the armored cruiser USS Birmingham, which occurred in Hampton Roads. It was followed on January 18, 1911 by the first aircraft landing on a ship, the USS Pennsylvania in San Francisco Bay. Those ships were stationary. The first landing by an aircraft on a moving ship was by a British pilot on HMS Furious.

in 1911, a plane landed on the USS Pennsylvania in San Francisco Bay and demonstrated the potential of creating a US Navy aviation program

Source: Smithsonian Institution, First Airplane Landing on a Ship

The United States was not the only nation developing a naval aviation program in advance of World War I, and seaplanes were utilized as well as aircraft launched from ships. The French invented seaplanes in 1910, and commissioned the first seaplane tender to lift seaplanes out of the water onto a ship in 1911. The first US naval aviation mission in direct support of ground troops was by a seaplane in Vera Cruz, Mexico, in 1914.

The first plane to be shot down in air-to-air combat was a Japanese floatplane downed by a German land-based airplane at Tsingtao (now Qingdao), China in 1914. The German pilot used a pistol; the aircraft itself carried no guns.

The first launch of an aircraft from a moving ship was by a British pilot in 1912. The first aerial torpedo attack was in 1915 by a British seaplane against a Turkish ship. The first air attack by planes from an aircraft carrier, rather than seaplanes taking off from the water, occurred in 1918. The British launched six planes from a battlecruiser that had been modified to serve as an aircraft carrier in order to damage a German Zeppelin base in Denmark.

The British started to construct the first ship intended from the beginning to be an aircraft carrier, the HMS Hermes, in 1918. The first ship designed o be an aircraft carrier and actually commissioned was the Japanese ship Hosho in 1922.

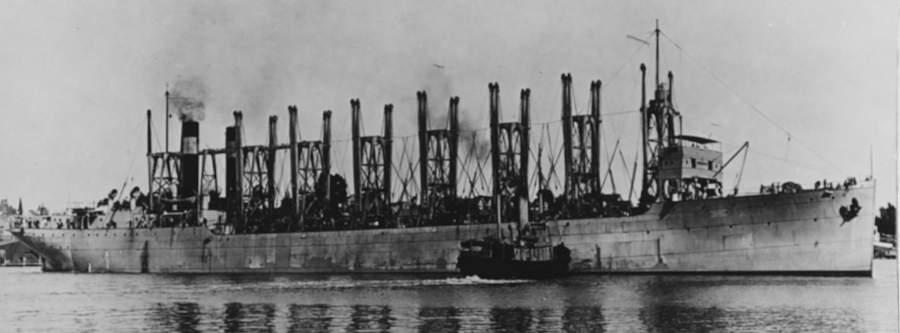

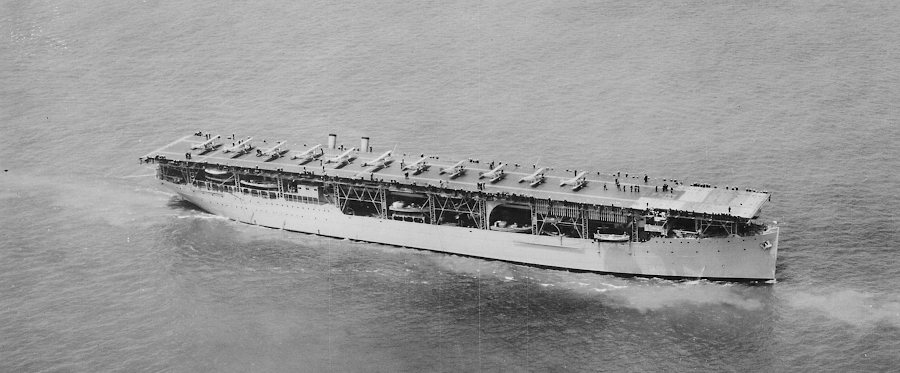

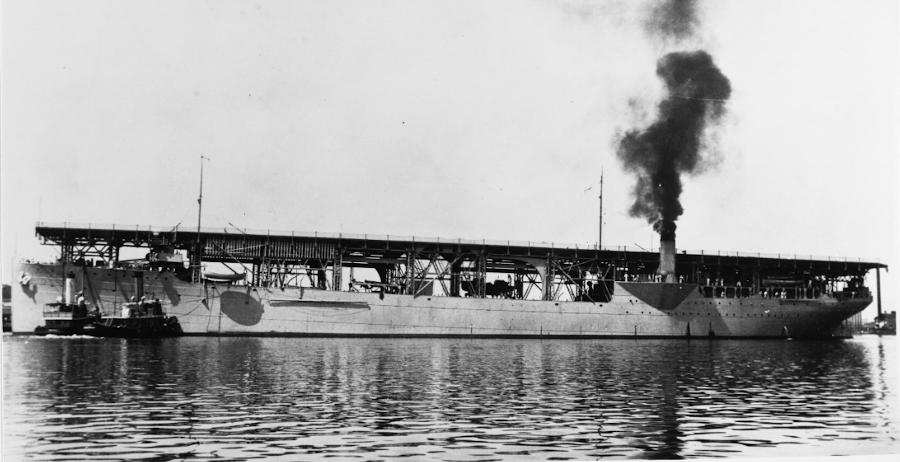

The first US Navy aircraft carrier for launching planes was the USS Langley, named after Samuel Langley. The US Congress authorized conversion of the USS Jupiter, built to carry coal, to an aircraft carrier in 1919. The ship was renamed the USS Langley in 1920 to honor Samuel Pierpont Langley. A full-length flight deck was constructed three feet above the main deck, creating the appearance of a covered wagon floating on the water.

a flight deck was constructed on top of USS Jupiter

Source: National Archives, Langley (CV1), formerly the Jupiter. Aerial, bow on, plane on deck, 08/03/1923

The catapult was located at the bow, and arresting wires at either end to enable recapture of aircraft no matter which direction the ship was sailing. On October 17, 1922 the first takeoff of an aircraft occurred while the ship was at anchor in the York River. A day later, the first catapult launch was also successful. That was soon followed by the first landing on the ship while it was steaming near Cape Henry.

Carrier pigeons were kept in a loft on the stern. US Navy aircraft used pigeons in World War I to transmit sightings of enemy vessels back to the ships. However, at one point when the USS Langley was at Tangier Island the entire flock chose to fly back to the Norfolk Naval Shipyard.

The first U.S. aircraft carrier that was designed from the beginning was the USS Ranger, completed in 1934. Unlike battleships, construction of aircraft carriers was not constrained by the post-World War I limit on capital ships.

The USS Langley was sunk by Japanese fighters on February 22, 1942 on its way to deliver fighter aircraft to Tjilatjap in the Dutch East Indies (now Cilacap, Indonesia).16

the coal-transporting collier USS Jupiter was converted into the first US aircraft carrier, the USS Langley

Source: National Archives, Langley Aerial, starboard bow, underway, aircraft on deck and US Naval Heritage Command, H-069-1: "The Covered Wagon" - USS Langley (CV-1)

The 13-acre Chopawamsic Island could have become a major tourist attraction. Kill Devil Hills would be just a pile of sand on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, known only to local residents and vacationers.

The Langley Flight Foundation, based in Stafford County, continues to highlight the role of Samuel Langley in pioneering heavier-than-air flight technology. Starting in 2019, it planned a $300,000 exhibit to display a replica of Aerodrome No. 5 at the Stafford Regional Airport, but the COVID-19 pandemic delayed the effort. A newspaper story in 2022 correctly noted that the May 6, 1896 flight of of Aerodrome No. 5 was:17

The replica of Aerodrome No. 5, in its May 1896 configuration, was installed in the Stafford Regional Airport in May, 2024.18

the argument that Samuel Langley was "first" is continued today by the Langley Flight Foundation

Source: Langley Flight Foundation, Chopawamsic Island Tour (August 1, 2022)

Source: Langley Flight Foundation, Langley and Aerodrome No. 5 - the First Heavier-Than-Air Mechanical Flight in Human History

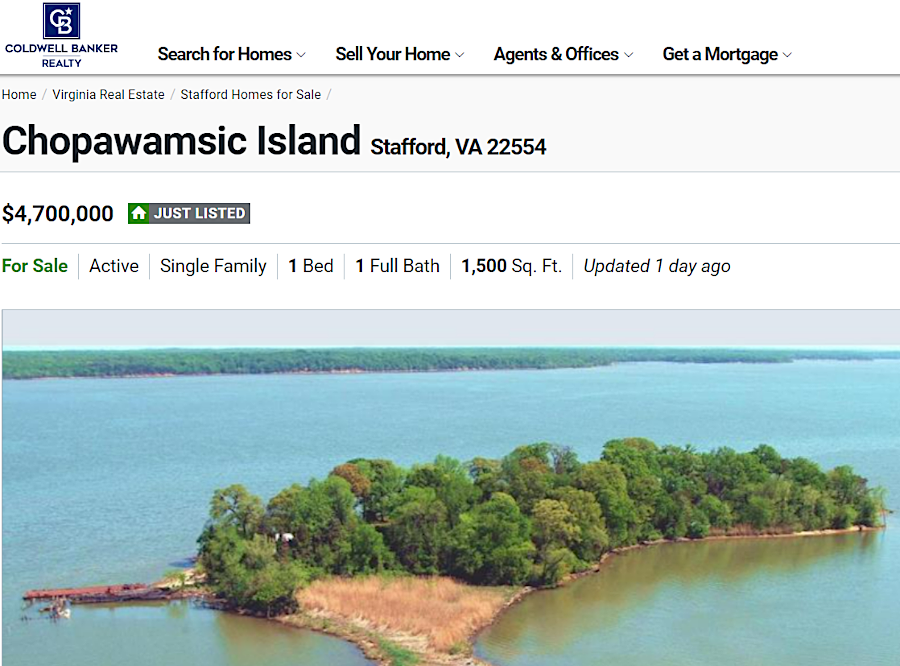

That island, also known as Chop Island and Scott's Island, is privately owned. The earliest records still surviving after the Civil War indicate that Rev. Alexander Scott owned it in 1724.

Though the US Marine Corps once published a story titled "Chopawamsic Island history dates back to 1649," people had been there for perhaps 20,000 years. When Paleo-Indians first arrived, sea levels were lower and the modern island was simply a high spot on the mainland near the edge of the Potomac River. Roughly 3,000 years ago, sea level rise following the melting on continental ice sheets finally flooded the area and made the site an island isolated from the mainland.

When John Smith and his fellow colonists explored the upper Potomac River in 1608, the site was on the edge of territory occupied by the Moyumpse (Dogue) to the north, the Patawomeck to the south, and the Piscataway on the eastern side of the Potomac River. By 1664, there were enough English colonists in the area to justify the creation of Stafford County. When the 1877 Mathews-Nelson survey defined the Maryland-Virginia boundary along the Potomac River downstream from Washington, DC, the line was drawn so the island stayed within Stafford County.

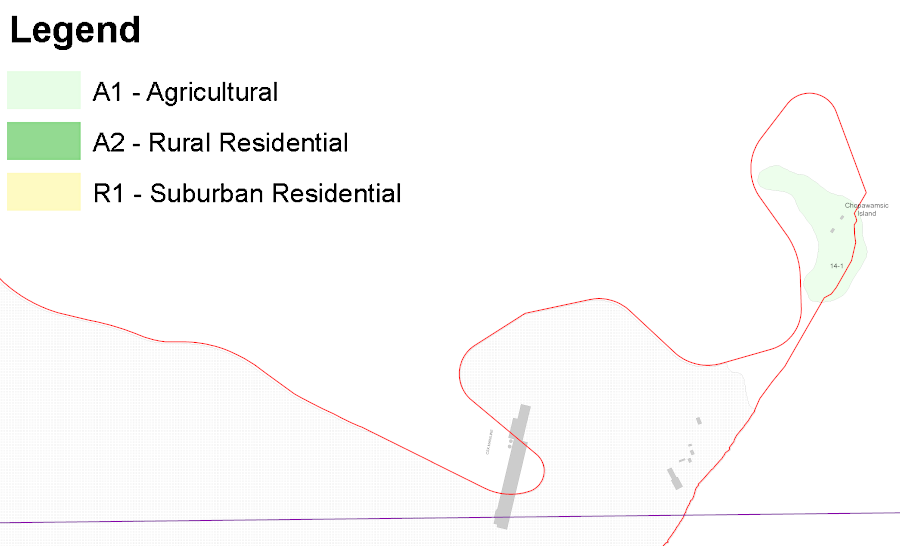

the 13 acres of Chopawamsic Island are in Stafford County, Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 1887, the Mount Vernon Ducking Association purchased the island and built a clubhouse for its wealthy duck hunting members. Reportedly Theodore Roosevelt was a member, as well as Samuel Langley.

Dr. Wesley and Emma Fry owned Chopawamsic Island between 1958-1979. Dr. Fry, a Navy captain and surgeon at the Marine Corps Base Quantico hospital, arranged with the Marine Corps to extend an underwater cable to the island to supply electricity. A 280' deep well provided drinking water.19

Real estate agents trying to sell the island in 1989 claimed that rezoning the island would enhance the tax base of Quantico, but that town is located within Prince William County. The Marine Corps had security concerns about private ownership of the island, noting:20

some Federal maps incorrectly place Chopawamsic Island in Prince William County

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Bathymetric & Fishing Maps

The Frys purchased the island in 1958 for $14,000. They were the last to live there. After selling it to Columbia Tours International in 1983, the island has been abandoned and the structures on it have decayed. A Stafford County real estate agent bought the island in 1991, then quickly resold it to Steve, Ray, and Abe Sami of Falls Church for $375,000.

They tried to sell it in 2018. They advertised a $15 million price, primarily to get attention, but found no buyer.21

The owners advertised Chopawamsic Island again for sale in 2022, with a $4.7 million price tag. The real estate agent suggested Langley Flight Foundation or Stafford County might purchase it to protect a historical site, but neither party indicated they were planning to buy the island.

The Stafford County tax assessment for the 13 acres of land in 2018 was $306,000, plus just $300 for "improvements" consisting of three dilapidated houses on the island.22

Chopawamsic Island was listed for sale in 2022 at a price of $4.7 million

Source: Coldwell Banker Realty, Chopawamsic Island Stafford, VA 22554 (August 31, 2022)

Chopawamsic Island consists of terrace deposits (sand/clay sediments) of the Potomac River, formed as the channel moved over the last 2.6 million years

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Geologic map of the Quantico quadrangle, Prince William and Stafford Counties, Virginia, and Charles County, Maryland (1972)

Orville Wright required the Smiothsonian to modify its interpretation of Langley's flights before donating his airplane to the museum

Source: Library of Congress - Chronicling America, Historic American Newspapers, Evening Star (May 2, 1925) and Evening Star (February 18, 1948)

Stafford County zoned the 13 acres of Chopawamsic Island as "Rural Agricultural"

Source: Stafford County, ArcGIS Online