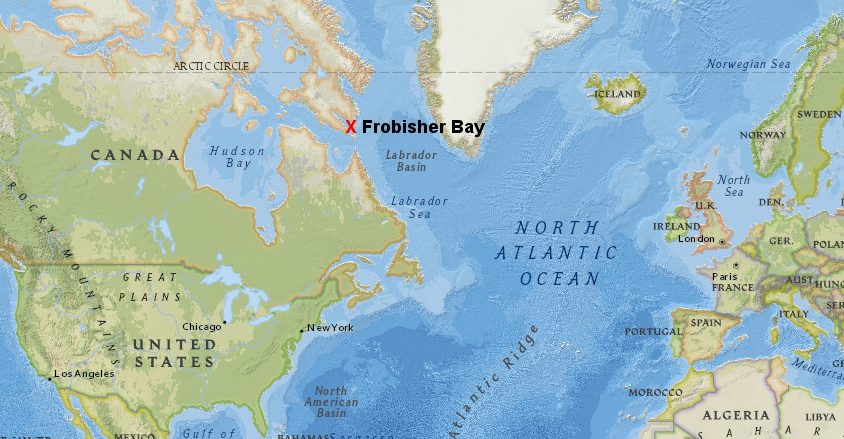

the first English colony was on Roanoke Island, sheltered from storms but difficult to access by ship

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the first English colony was on Roanoke Island, sheltered from storms but difficult to access by ship

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Sailors exploring the western edge of the Atlantic Ocean were the first English to see Virginia. Since England is an island separated from Virginia by an ocean, no one could walk from London to the Chesapeake Bay.

The first English expeditions to the New World were sponsored by merchants in Bristol. Ships from Bristol had been exploring in the North Atlantic, west of Ireland, for new markets since the 1480's.1

After Christopher Columbus "discovered" islands in the Caribbean in 1492, Bristol merchants funded an expedition to discover a route to China. Henry VII authorized an Italian sailor, Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot), to discover lands not already claimed by Spain. His first expedition in 1496 was a failure, but he probably saw Newfoundland on his second voyage in 1487. In 1498, Cabot sailed west for a third time with five ships, but all disappeared.

by 1541, European fishing camps were scattered across Labrador and Newfoundland

Source: Barry Lawrence Ruderman, Early Photographic Facsimile of the 1541 Nicolas Desliens Planisphere

Fishermen from Europe, particularly the Portuguese, French, Basques, and English, quickly took advantage of the rich resources of the Atlantic Ocean off the coastline of what today is Canada. Fishing camps were scattered along the coastline, as documented by maps dating back to 1541. St. Johns, the modern capital of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, claims to be "the oldest English-founded city in North America." However, permanent settlement became established only by 1610.2

St. Johns claims to be the oldest English-founded city in North America

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

It took nearly a century after Columbus reached the Caribbean before England seriously began to exploit the potential of the New World. Internal disputes during the era of King Henry VIII and his first two successors, Edward VI and Mary I, reduced the capacity of the wealthy elite to fund high-risk journeys of exploration and settlement.

In 1576, eighteen years after Queen Elizabeth I assumed the throne, Queen Elizabeth I authorized Martin Frobisher to find the fabled Northwest Passage, and he sailed far north near the Arctic Circle on three expeditions. Frobisher tried to establish a colony on Baffin Island in 1578.

in the 1490's, merchants in Bristol funded the first English efforts to discover the Northwest Passage through North America to China

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Everyone who initially settled on land returned to England at the end of the summer, when the ships sailed home with what was thought to be gold ore. When the ore was revealed to be just iron pyrites ("fools gold"), venture capitalists backing Frobisher's journeys withdrew their financial support.3

the first English settlement attempt in the New World was in the high latitudes, where Martin Frobisher hoped to discover the Northwest Passage

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

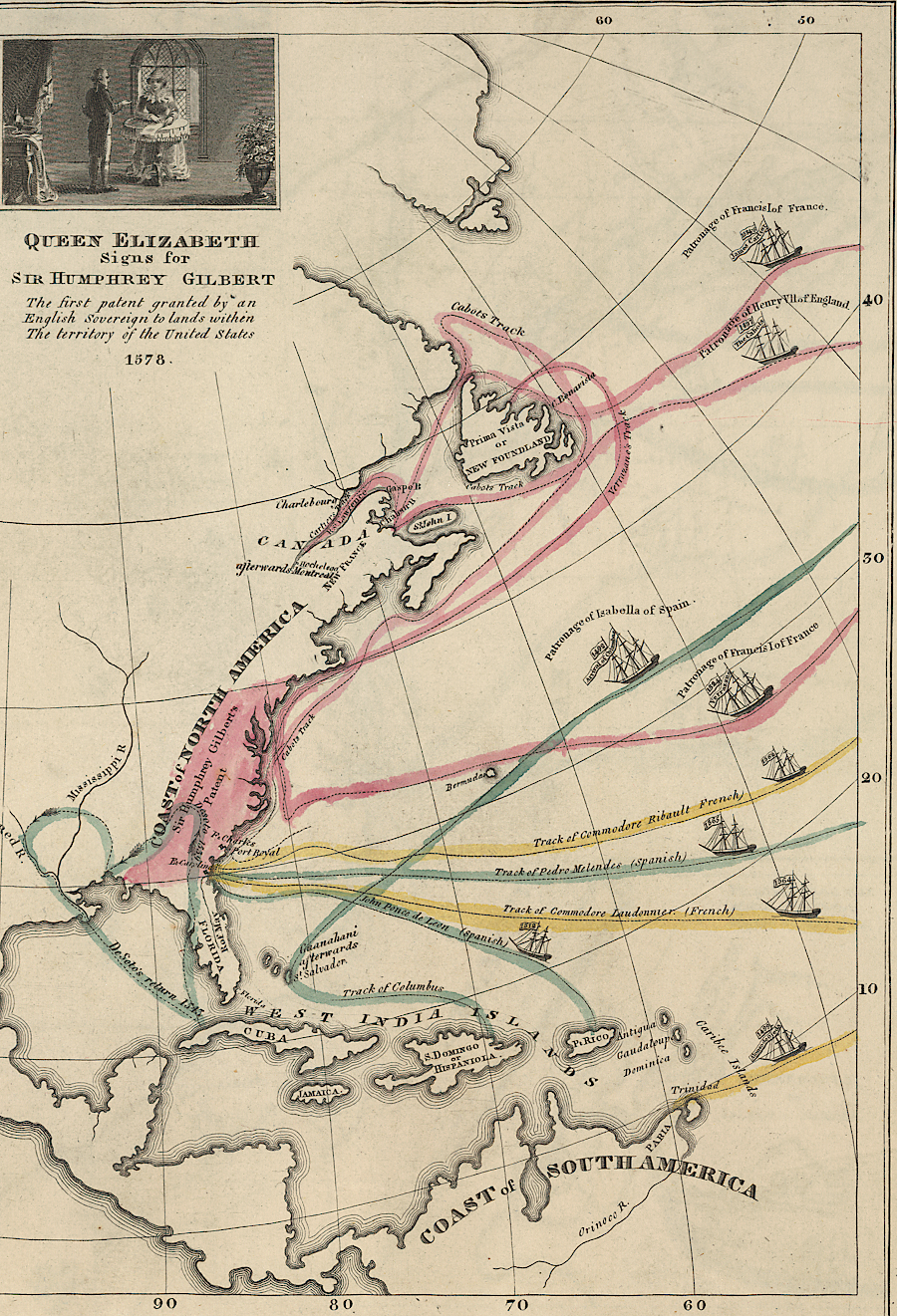

In 1578, Queen Elizabeth I granted a charter to Sir Humphrey Gilbert to create a permanent colony in North America. Gilbert had written A Discourse of a Discoverie for a New Pasage to Cataia, making a serious proposal for a settlement in North America in "Norumbega." To obtain permission for the expedition, he had some of the first English maps of North America prepared.

He too highlighted the economic benefits of discovering the Northwest Passage to Cathay (China, or "Cataia"). By 1578, however, his proposal was in conflict with the Muscovy Company's exclusive rights to trade between England and Russia.4

Gilbert had some of the first maps of North America prepared in England for his journey to Norumbega

Source: Free Library of Philadelphia, Gilbert, Sir Humphrey. Humfray Gylbert knight his charte. T.S.[i.e. John Dee] fecit. [ca.1582-1583]

The Muscovy Company had been established in 1555, after English sailors reached the northern coastline of the Duchy of Muscovy (now Arkhangelsk in Russia) and defined a Northeast Passage. The English sought to dominate the fur trade between Europe and Siberia, and to find a port with an overland route with China that was not contested by the Spanish, Portuguese, or Hanseatic League which dominated the Baltic Sea.

the Northeast Passage failed to develop into a major trade route that would bypass the barriers blocking the English from acquiring Chinese goods

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In the Sixteenth and Seventeenth centuries, kings and queens of England depended upon the private sector to finance the expansion of the country's economic and political power through discovery. The first English efforts to settle in North America were by private corporations and venture capitalists seeking profit through exploration, with minimal government support.

The Muscovy Company was the first joint-stock company in Elizabethan England. At the time, no single family could finance high-risk explorations to exploit the Northeast Passage or discover the fabled Northwest Passages.

The joint-stock company pioneered by the Muscovy Company allowed enterprising individuals to pool a portion of their capital and "adventure" those funds in hopes of getting rich. That established an economic model for private capitalists to finance exploration 50 years before the Virginia Company funded settlement in Virginia. Today's venture capitalists follow the pattern established in the 1500's of pooling accumulated wealth and sharing risks.

In the modern era, space exploration offers the closest parallel to the opportunities provided by exploration of North America 400-500 years ago. However, governments funded the initial efforts in space. The United States, Russian, and European governments paid the costs for initial launches of satellites and humans for the first 50 years, in contrast to the model used by Queen Elizabeth I to rely upon private financing in the 1500's. Venture capitalists began funding near-earth spaceflights starting in the early 21st Century, but inter-planetary probes still rely exclusively upon government funding.

In the 1570's, all of England would benefit if Humphrey Gilbert used his authorization from the queen and discovered a Northwest Passage to China and Russia, but the stockholders of the Muscovy Company wanted to be sure that their investments would be protected, however, and it interfered with proposals by other English capitalists to settle the eastern coast of North America.5

Sir Humphrey Gilbert risked more than his money. He personally led the exploration to the New World in 1583, five years after a 1578 attempt was forced by bad weather to return almost immediately to England. Gilbert landed on Newfoundland, attempting England's first attempt at establishing a colony in the New World, but no permanent base was established. He died when his ship disappeared on the return journey.6

Sir Humphrey Gilbert "ventured" his life and purse - and his ship disappeared on the return trip from the 1583 expedition to Newfoundland

Source: Library of Congress, First Map or Map of 1578 (by Emma Willard, 1838)

Gilbert's half-brother, Walter Ralegh, quickly obtained a renewal of the charter or "Royal Patent" in 1584. Ralegh decided to move the location of the proposed colony further south. Though the climate would be warmer than Newfoundland, the colony would be closer to the Spanish in the Caribbean so the danger of attack would be much higher.

Ralegh sent a scouting party to North America in 1584, commanded by Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlow. They reconnoitered Roanoke Island and returned with two Native Americans, Manteo and Wanchese. Carrying those two men to England provided a rare attraction that was useful in marketing the venture to potential investors, plus an opportunity to create translators between Algonquian and English languages.

Learning to communicate started with confusion over the names of the place where the English landed. The English asked the Native Americans what was the name of their land, and they replied "Wingandacon." However, that response had nothing to do with the question asked in English; instead, the Native Americans had said in their Algonquian language "you wear fancy clothes." The actual name of their land apparently was "Ossomocomuck."

Ralegh honored Queen Elizabeth I and helped cement his authorization for exploration by naming the place "Virginia." Queen Elizabeth I declined to marry any of the available European princes, since such a marriage would establish an alliance, so in theory she was always a virgin queen. Spain was the strongest nation, so marrying a non-Spaniard could trigger a war which England might lose.

Marrying a Spaniard like her half-sister Mary would trigger a reaction by France and others who feared Spanish hegemony, threatening war from a different direction. Marrying a Spanish prince would also create an uproar within England, which was dominated by Protestants who considered Catholic Spain to be a threat rather than a potential ally.

The first recorded use of the term "Virginia" is on a seal that identified Raleigh as governor of Virginia. That document was issued in late 1584 or early 1585. Ralegh had declined to use "Ossomocomuck."

As part of his efforts to attract the queen's support, Ralegh arranged for the younger Richard Hakluyt to write a Discourse on the Western Planting articulating reasons for supporting colonial expansion.

Ralegh's hopes that Queen Elizabeth would respond to flattery or to reason by funding future expedition were not rewarded. She knighted him, but only loaned a small navy vessel to his efforts. At the time, she feared a Spanish reaction to open government support of colonization in La Florida. The Spanish had slaughtered French colonists in 1565 after they attempted to create a colony at La Caroline (now Jacksonville, Florida).

In 1585 Raleigh sent seven ships with 600 soldiers on an expedition across the Atlantic Ocean under Ralph Lane and Richard Grenville. They planned to create a military base with 300-400 people settling on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. The base would support efforts of English privateers to loot Spanish settlements in the Caribbean, and to seize Spanish ships sailing from Europe with valuable supplies or back to Europe with treasure:7

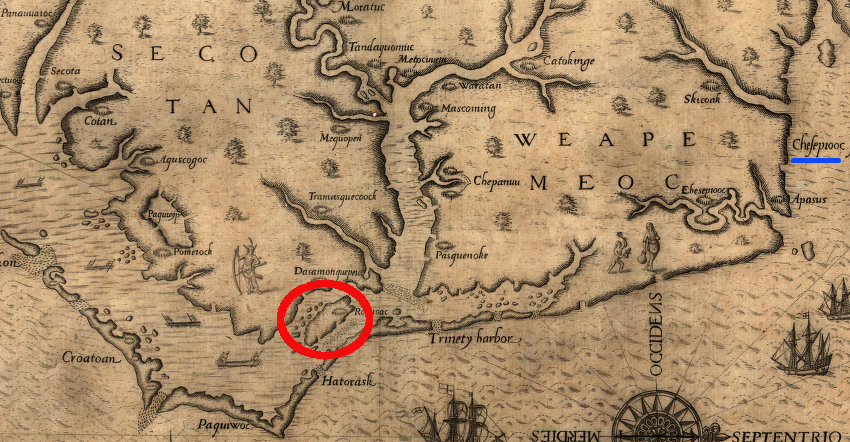

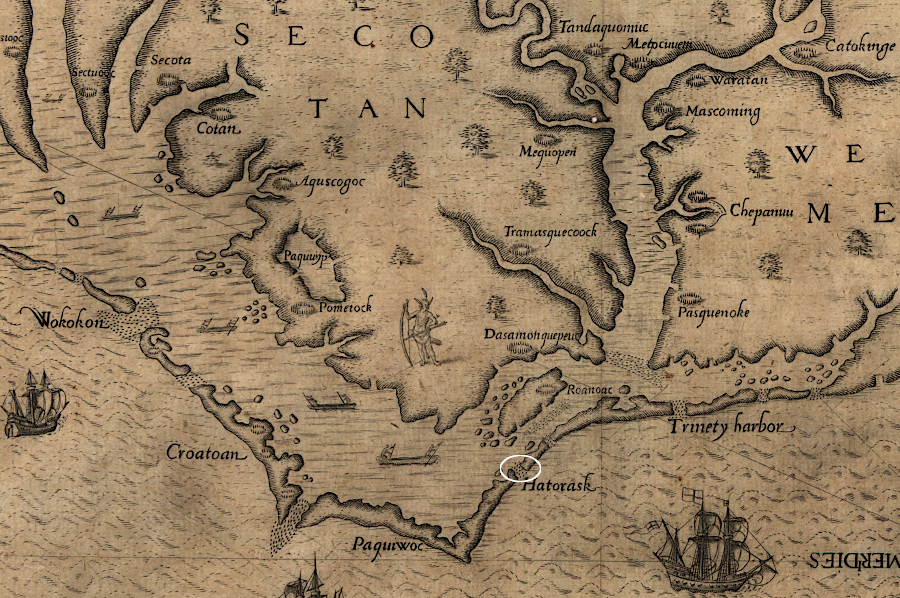

Location of Roanoke Island and Chesapeake Bay, White-De Bry Map of Virginia (1590)

Source: Library of Congress

The seven ships under Ralph Lane and Richard Grenville arrived at the Outer Banks in June, 1585. A second fleet was supposed to sail from England in June 1585 to support the new settlement. Starting the colony was an expensive venture. Unless there was gold or silver to seize, as the Spanish had done in Mexico and Peru, colonization could require years before benefits exceeded expenses.

The resupply fleet was diverted after relations with Spain deteriorated. The second fleet was directed to sail to the fishing grounds off Newfoundland, where it captured 17 vessels. The attack on the Spanish fishing fleet was facilitated by some of the ships returning from the Outer Banks under Richard Grenville. Privateering on the trip back to England provided a quick return on investment, and showed how Virginia could serve as an effective base for capturing Spanish ships.8

the planned 1585 supply mission to the Outer Banks (red X) was diverted to seize Spanish ships on the Newfoundland fishing grounds

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Ralph Lane had stayed in what Ralegh called "Virginia" when Richard Grenville sailed home in 158 (with his stop in Newfoundland to attack the Spanish fishing fleet). Lane soon moved the settlers north from Wococon (near Ocracoke) to Roanoke Island. Since the English had arrived so late in the summer of 1585, there were no crops in the ground that required the colony to stay on Wococon.

During the winter of 1785-86, Ralph Lane sent a party of settlers further north to meet with additional Native American groups and to explore the potential of establishing a settlement at a site with a better harbor. The expedition met the Chesapeakes, whose controlled the territory east of what is now called the Elizabeth River and the Atlantic Ocean. The colonists may have stayed in the town of Chesepiuc near modern Lynnhaven Bay between October 1585-February 1586. They met other Algonquians from the Coastal Plain, and perhaps Iroquoian-speaking Native Americans who lived on the Meherrin and Nottoway rivers.9

John White sketched the locations of the islands of Wococon and Roanoke, plus the towns of Skicoak and Chesepiuc (near where some English colonists may have spent a portion of the winter of 1585-86)

Source: British Museum, Map of the E coast of N America from Chesapeake bay to Cape lookout

The English may have been peaceful when visiting briefly near Lynnhaven Bay, but on Roanoke Island their aggressive violence alienated the local chief Pemisapan (who was known as Wingina when the English first arrived). Pemisapan sought to mobilize other tribes to exterminate the English, but Ralph Lane struck first. His colonists killed Pemisapan and decapitated him on June 10, 1586.10

Ralph Lane expected to move north from Roanoke Island after the corn was harvested in July, re-establishing the colony on the south shore of what would later be called Hampton Roads.

However, Francis Drake arrived on June 11, 1586. He had raided Spanish outposts further south at Santo Domingo and Cartagena with great success, but then abandoned plans to cross the Isthmus of Panama or to capture/garrison Havana until another fleet from England would bring reinforcements. After sailing through the Florida Channel, he had destroyed the wooden fort and town at St. Augustine in Florida.

Drake offered to supply Lane and the colony with new supplies, including clothing, furniture, and hardware for constructing houses (which the English had stripped from St. Augustine before burning it). Lane was most interested in the pinnaces and small boats that Drake would provide, because they would facilitate exploration of the shallow waters of the "Virginia" coast from the Outer Banks north to the planned new settlement location on the Chesapeake Bay.

Drake had extra men, including 300 South American Indians and 100-200 black slaves captured in the Caribbean. They were part of the wealth captured from the Spanish. Removing them from Cartegena weakened the Spanish, but Drake's objective might have been to gift them to the new English colony getting established on Roanoke Island. That would give it a major boost in manpower.

The new English colony was not thriving, however. The major challenge was acquiring enough food for the English who had migrated to North America. The corn crop on the island would not be ripe for another month, so feeding even more mouths brought by Drake was not feasible. Richard Grenville was supposed to bring food from England, but he was overdue. It was possible that the planned resupply from England might not ever arrive.

While Lane and Drake were discussing options, a hurricane struck and destroyed several ships. That storm shaped the decision. On June 18, 1586, Lane and the other colonists hurriedly abandoned the Virginia colony at Roanoke Island and returned to England with Drake. Three English men were left behind, becoming the first "lost colonists."

It is likely that Drake also offloaded the Africans and Native Americans that he had seized at Cartagena. Feeding them plus the 150 colonists during a trip across the Atlantic Ocean would have been difficult. Assuming the captives from Cartagena were left behind, they either died or were incorporated into the Native American communities on the mainland. The English who returned in 1587 to re-start their colony never reported finding evidence of them.

Drake's delivery of captive Africans and South American/Caribbean Native Americans that he stole from the Spanish is rarely acknowledged in the standard histories of English colonial settlement of North America. Andrew Lawler suggests in The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession, and the Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke that the traditional description of the Roanoke Island colony should be revised:11

About two weeks after Lane and Drake abandoned the colony and left for England, Richard Grenville finally arrived with the resupply and 300-400 new colonists. Greenville chose to return back to England with all but 15-18 men, who were left with enough supplies to survive for one or two years.12

John White's paintings of the first English settlement in Virginia in 1585-86 included "La Virginea Pars," a map of the southeastern seacoast from Florida to the Chesapeake Bay

Source: British Museum, La Virgenia Pars; map of the E coast of N America from Chesapeake bay to the Florida Keys

In 1587 Ralegh partnered with others to send another group back to New World. That group (including women and children) was led by John White, who had been with the colonists that arrived in 1585 and returned with Drake in 1586. The intent was to build a long-term settlement with over 100 colonists somewhere north of Roanoke Island, possibly in the territory of the Chesapeakes.

The original location of Roanoke Island in the Outer Banks would be maintained as a military base, with additions to the men left by Grenville in 1586. All of the colonists going to the new site near the Chesapeake Bay were to receive 500 acres of land.13

After reaching Roanoke Island, White discovered that Grenville's men had disappeared (the second set of "lost colonists"). The expedition's pilot, Simon Fernandez, was unwilling to continue north. Fernandez's priority may have been to capture prize ships, and delivering the colonists to a new location would delay his opportunity to get rich through privateering.

small English ships passed though a now-closed inlet into Pamlico Sound, to reach Roanoke Island

Source: Library of Congress, Americæ pars, nunc Virginia dicta

The colonists who arrived in 1587 were dropped off at Roanoke Island, not at the planned location further north on the Chesapeake Bay. Before the ships returned, White's daughter had a baby (Virginia Dare) and a child was born to the Harvie family as well. Virginia Dare is often described as "the first English-born child in the Americas."14

Key to that claim is that her mother was English. English sailors on previous expeditions, as well as their Spanish counterparts, may well have fathered children with Native American mothers.

White did not remain with his new granddaughter or the colony. He returned back to England to notify the financial backers about the failure to find Grenville's men on Roanoke Island (the second batch of "lost colonists") and the failure to establish a settlement on the Chesapeake Bay as planned.15

Ralegh was unable to send another expedition immediately. His large 1588 expedition was blocked by an order from the privy council; all ships were required to defend England from Spanish attack. Ralegh was able to send two small vessels with John White, but they ended up privateering and fighting French ships and never crossed the Atlantic Ocean.

The Spanish sent a ship from the Caribbean into the Chesapeake Bay in 1588, and in 1606 still believed the colony existed, but there is no documentation in the Spanish archives that they visited or attacked the Roanoke Island settlement. In Europe, the Spanish Armada was defeated in 1588 but the threat of invasion continued for several more years. No resupply mission to Roanoke Island was launched in 1589.

Queen Elizabeth's interest in expanding English power into North America was well known. In what is now called the Armada portrait of her, painted after the defeat of the Spanish in 1588, her hand rests on a globe where Virginia is located.16

in the "Armada portrait" of Queen Elizabeth, rich in symbolism, her hand rests not on England but on Virginia to suggest her interest in colonization

Source: Royal Museums Greenwich, Symbolism in portraits of Elizabeth I

The English ships that finally reached Roanoke Island in 1590 were a privateering expedition. They agreed to stop at Roanoke Island only in order to get authority from royal officials to sail across the Atlantic Ocean, at a time when the Spanish threat was still high and ships were being kept close to port in case of another attack. Three privateers were supposed to carry supplies and passengers to Roanoke Island, and two others agreed to stop there.

It appears some of the promised supplies were loaded in England, but no passengers other than John White. Travel across the ocean was slow, as the privateers laid in wait along sea lanes and sought to intercept Spanish ships to capture as prizes. The main plan was to lurk around the West Indies to determine when the Spanish treasure ships sailed east, then send a fast ship to an English fleet waiting at the Azores. The English ships in the Caribbean would also sail east to help intercept the Spanish fleet near the Azores.

English ships sailing to North America resupplied at the Azores - and at times tried to capture Spanish ships there

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Sailing north to check on the colonists left on Roanoke Island in 1587 was not consistent with this strategy. Only two of the privateers went to the Outer Banks, and they did not arrive until hurricane season had started in August, 1590.17

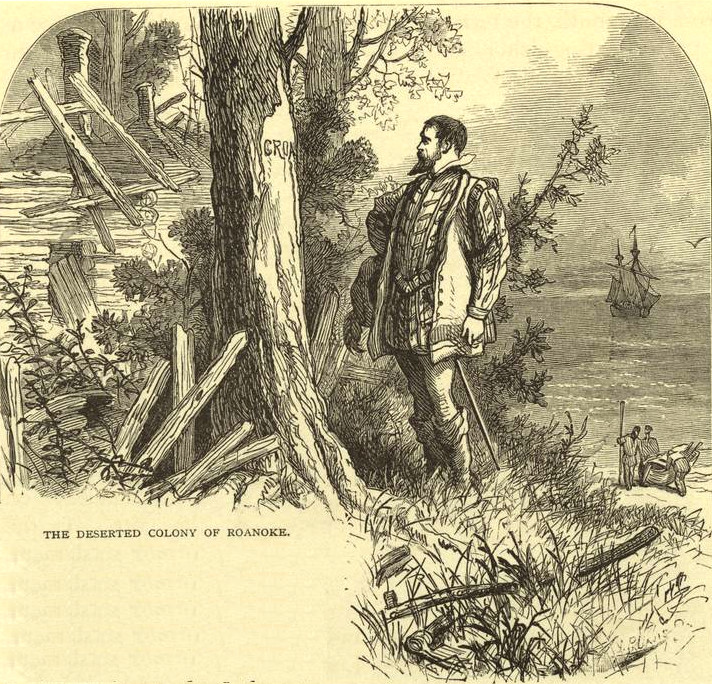

When White returned he found only "CRO" carved on a tree and "CROATOAN" on a post. The ships sailed away without examining Croatoan (Hatteras) Island in detail due to approaching storms.

in 1590, John White found only CRO and CROATOAN carved into trees

Source: New York Public Library, The deserted colony of Roanoke (1876)

John White never saw his granddaughter Virginia Dare again, and the settlers at the "Lost Colony" were never found. For the next 15 years, English capitalists focused on quick profits from privateering, and dropped their interest in creating either a military base or a colony on the North American coastline.

Ralegh's patent giving him exclusive rights to settle near Roanoke Island expired in 1590. He might have obtained a renewal, but in 1592 Queen Elizabeth discovered he had secretly married one of her maids of honor without the queen's permission. She jailed him in the Tower of London, and upon his release he shifted his focus to finding the rumored city of gold (El Dorado) in South America. In 1602 Ralegh funded a trip to Cape Fear, but that expedition only collected sassafras (used as a drug in Europe) and did not search for the "Lost Colony" 175 miles to the northeast.

later English colonists chose to settle on the Chesapeake Bay because shifting sands and inlets made it had for ships to get to Roanoke Island

Source: Library of Congress, A new map of the country of Carolina

The colonists left behind in 1587 may have moved north and lived with the Chesapeake tribe on the Elizabeth River (near modern Norfolk/Virginia Beach). The original plan for that 1587 expedition was to settle on the Chesapeake Bay where there was a good harbor, and leave just a military/privateering base at Roanoke Island.

Powhatan, the paramount chief of the Algonquians on the Coastal Plain of Virginia, destroyed the Chesapeake tribe just before the 1607 arrival of the English colonists who established Jamestown. If any of the 1587 colonists on Roanoke Island (such as Virginia Dare and the Harvie child) had survived until then, they would have been fully integrated into the Algonquian culture. They may not have welcomed any "rescue" by the Jamestown colonists and transport to an alien society in Jamestown.18

key locations in English attempts to create a military/privateering base and colony on the Atlantic Coast between 1584-1590:

1) Roanoke Island 2) Croatoan (Hatteras) Island 3) planned location for 1587 settlement 4) possible fort 50 miles inland

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Some researchers claim the evidence proves the 1587 colonists moved to Hatteras Island to live with the Croatoans, rather than migrated north to join the Chesapeakes. Alternatively, the colonists could have moved inland to live with friendlier Native Americans where the Chowan and Roanoke rivers reach Albemarle Sound.

Source:

WHRO Public Media, Lost Not Lost, After All?

The English men were not known for their sensitivity towards other cultures. If the local residents objected to the colonists' assertive/arrogant behavior, then the men might have been killed. The women and children had a greater chance of being incorporated into the Native American towns, and their genes may still survive in the area. If so, they are also blended with the genes of enslaved men and women who fled into the wetlands in the 1700's to join what were then called the Machapunga.

National Geographic theorized in 2018:19

Scholar James Horn believes that most colonists that survived until 1607 were killed by a raiding party sent under orders from Chief Powhatan (Wahunsonacock):20

In 2012, British Museum officials examined a patch covering a spot on one of John White's maps, "La Virginea Pars." They discovered underneath the patch a four-pointed star, indicating the site of a previously unknown fort that could have been a re-settlement site on the Chowan River.

White may have purposely omitted references to that location in his writings, other than making a vague reference to a site 50 miles inland, because the Spanish had spies with access to documents circulated within the English court.

Another possibility is that other reports (now lost) detailed how the colonists might move inland from Roanoke Island, since ships had such difficulty getting through the shallow shoals of the Outer Banks. One speculation is the location was kept as a competitive secret, since an inland fort could become a base for collecting high-value sassafras used to treat venereal disease.21

the "La Virginea Pars" map by John White has a patch that obscures the outline of a fort at the mouth of the Chowan River

Source: British Museum, La Virgenia Pars; map of the E coast of N America from Chesapeake bay to the Florida Keys

After 1590, English and other European ships continued to sail past the North American coastline north of St. Augustine. An English ship brought Native Americans from the Rappahannock River back to London in 1603, after a violent incident in which the Native American ruler was killed.22

By the time Jamestown was settled in 1607, the Europeans had a familiarity with the coastline of North America equivalent to what we know today of the moon. Some areas they knew well from multiple visits, while other locations were largely unexamined. Inland, however, the geography was poorly understood for a century after the 1587 Roanoke Island settlement became the Lost Colony.

The dream of a Northwest Passage around the continents of Asia and North America never disappeared. As the climate warmed and Artic ice retreated, a northern shortcut became realistic in the 21st Century.

In 2019 the US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, suggested that ships could reduce the time required to travel between Asian and western ports by 20 days, and:23

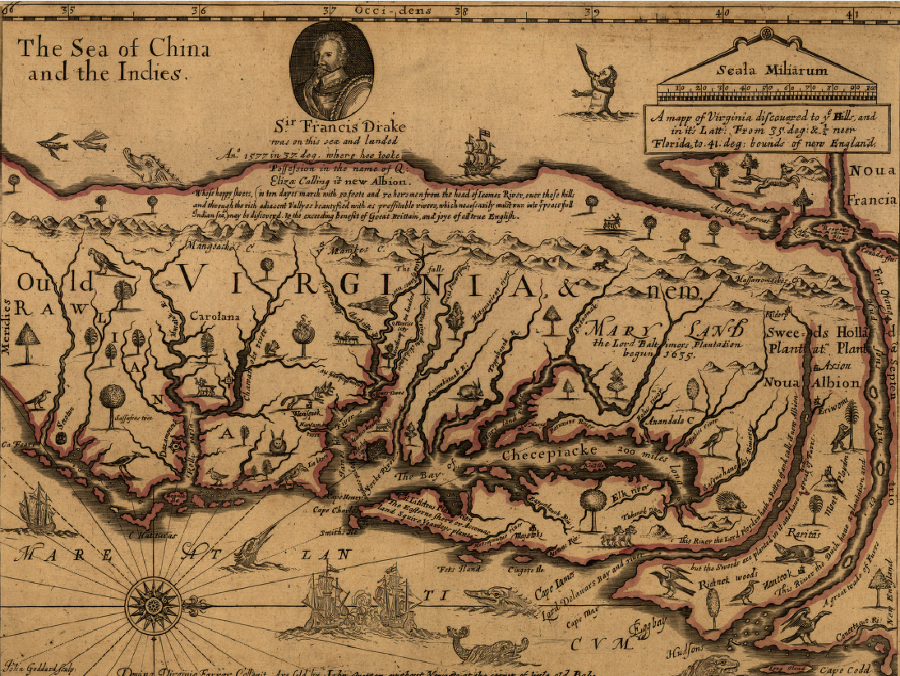

in 1651, John Farrer still identified the lands south of the James River as Rawliana

Source: Library of Congress, A mapp of Virginia discovered to ye hills, and in it's latt. from 35 deg. & 1/2 neer Florida to 41 deg. bounds of New England (1657 revision by Virginia Farrer of 1651 map by her father John Farrer)

in 1588, Theodore de Bry's engraving of John White map was published in Thomas Hariot's book A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia

Source: Learn NC, The Carte of all the Coast of Virginia

80 years after the attempt to settle at Roanoke Island, the English had a poor understanding of inland geography - John Ferrar's 1667 map indicated the Pacific Ocean was only a 10-day march from the headwaters of the James River

Source: Library of Congress, A mapp of Virginia discovered to ye hills, and in it's latt. from 35 deg. & 1/2 neer Florida to 41 deg. bounds of New England (1657 revision by Virginia Farrer of 1651 map by her father John Farrer)