Edward Bland and Abraham Wood

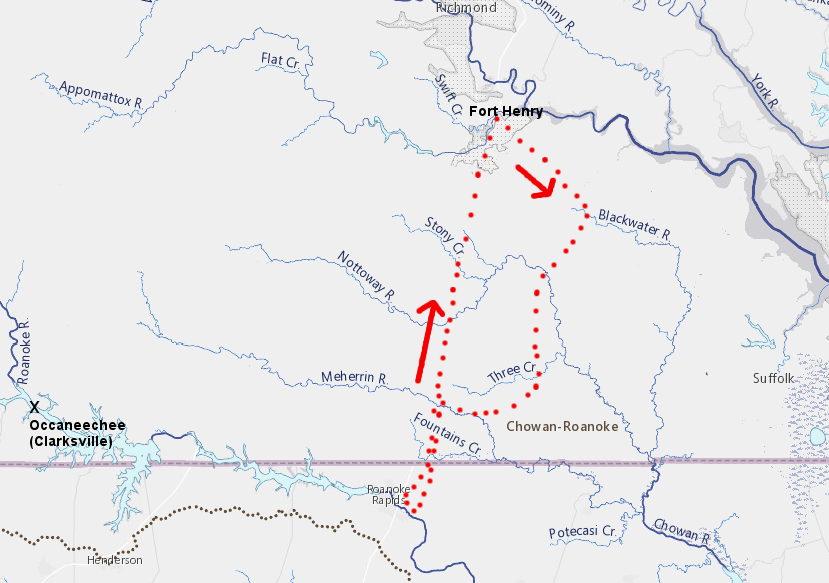

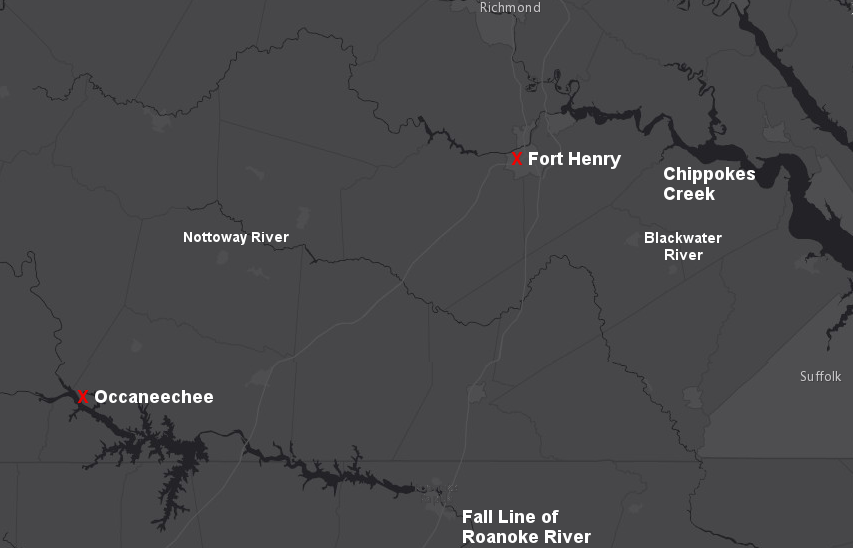

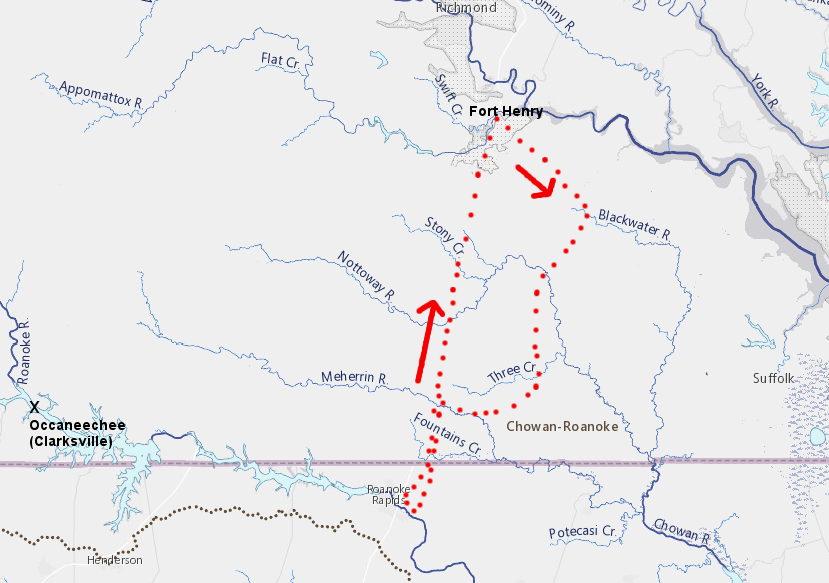

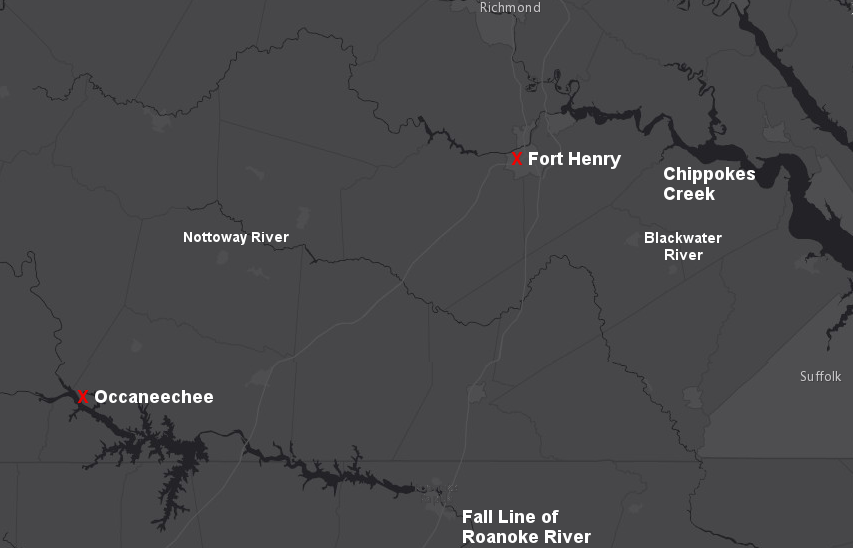

the most likely route taken by Edward Bland and Abraham Wood's 1750 expedition from Fort Henry to the Roanoke River was via the Blackwater River initially, and did not follow the Occaneechee Path to the existing trading center near modern-day Clarksville (as determined by Alan V. Briceland)

Source: The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, The Search for Edward Bland's New Britain (1979)

In 1646, two years after Opechancanough had organized a second major uprising, the General Assembly ordered construction of Fort Henry at the falls on the Appomattox River. Captain Abraham Wood was given responsibility for the site and the 45 soldiers to be stationed there. 1

The Third Anglo-Powhatan War ended the same year with a peace treaty signed by Necotowance, successor to Opechancanough after that leader of the Powhatan paramount chiefdom had been murdered while in custody. The expense of maintaining the fort became unnecessary, so the colony transferred responsibility for Fort Henry to Captain Abraham Wood.

The 1646 act required Abraham Wood to keep 10 men at the old fort. It was, at the time, on the southwestern edge of colonial settlement in Virginia. Wood had few local customers, and ships sailing up the James River could load cargoes and sell their imported goods long before reaching the Fall Line on the Appomattox River. Wood himself had a plantation on Upper Chippokes Creek,

Wood did have a valuable advantage in operating the fort as a trading post. The 1646 treaty had required Native Americans doing business with the colony to go to only four locations. Two were located north of the James River. South of the James River, Fort Henry and the home of John Floyd across the Appomattox River were the two authorized locations:2

- that upon any occasion of message to the Gov'r. or trade, The said Necotowance and his people the Indians doe repair to fforte Henery alias Appamattucke fforte, or to the house of Capt. John ffloud, and to no other place or places of the south side of the river

Fort Henry (and John Floyd's house across the Appomattox River) were designated in 1646 as the two authorized locations for Native American-colonial trade south of the James River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Abraham Wood ran a fur trading business at Fort Henry, and was proactive in seeking additional customers from Native Americans in the region who would sell furs and buy supplies. He linked up with a merchant named Edward Bland, and the two of them led four others on August 27, 1650 from Fort Henry on an expedition to the Roanoke River. They called the Roanoke River the "Blandina River" to honor Bland, and named the territory there "New Brittaine."

They sought to obtain intelligence about the local tribes and the territories in which they hunted, and to build relationships with potential suppliers of deerskins and various furs. Wood and Bland may also have sought to identify the location of valuable minerals and other natural resources, which could be acquired through future land grants. In the report of their stay on the "Blandina River," Edward Bland wrote:3

- we saw among them Copper, and were informed that they tip their pipes with silver, of which some have been brought into this Country, and 'tis very probable that there may be Gold, and other Mettals amongst the hils.

The group also thought they might encounter Englishmen or an English woman living with the Tuscarora, perhaps survivors or descendants of the "lost" Roanoke colony:4

- we had information that at that time there were other English amongst the Indians

-

Searching to survivors of the "Lost Colony" had started over 40 years earlier. John Smith, when president of the Council in 1608, pressured the werrowance of the Warreskoyack to provide guides for Michael Sicklemore to explore south towards the town of Choanoac on the Chowan River.

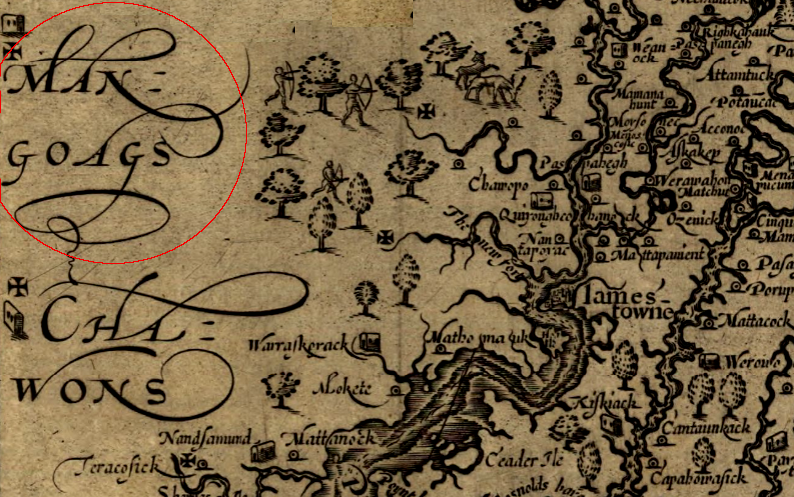

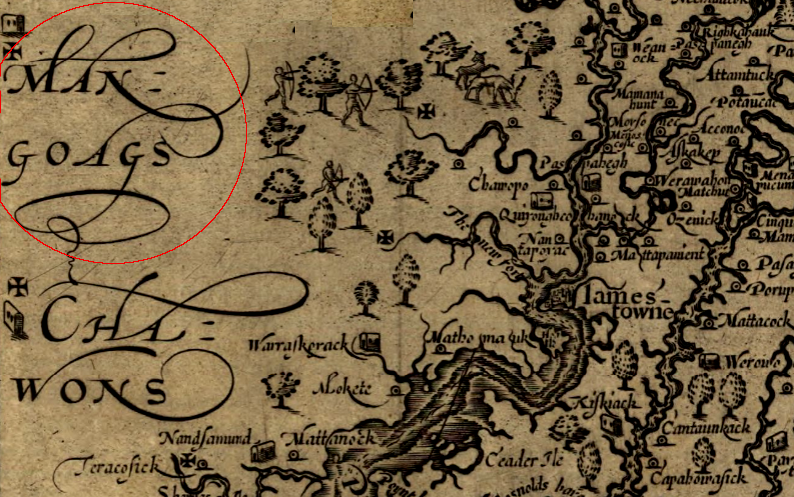

In 1609 Smith had the Quiyoughquohanock provide guides for Nathaniel Powell and Anas Todkill to explore through the territory of the "Mangoags," perhaps the Iroquoian-speaking Nottoway, Meherrin, and Tuscarora. John Pory's exploration to the Chowan River in 1622 was equally unsuccessful.5"

John Smith sent two explorations south from the James River through the land of the Mangoags towards the Chowan River, seeking information about the colonists lost on Roanoke Island

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

The 1650 Wood-Bland expedition initially relied upon a man named Pyancha from the local Appamattuck tribe to be initial guide and translator. His native language would have been an Algonquian dialect, and the travelers crossed lands of similar-speaking Weyanoke. After crossing the Blackwater River, however, the expedition entered territory controlled by Iroquoian-speaking Nottoway, Meherrin, and ultimately Tuscarora ("Tuskarood") groups.

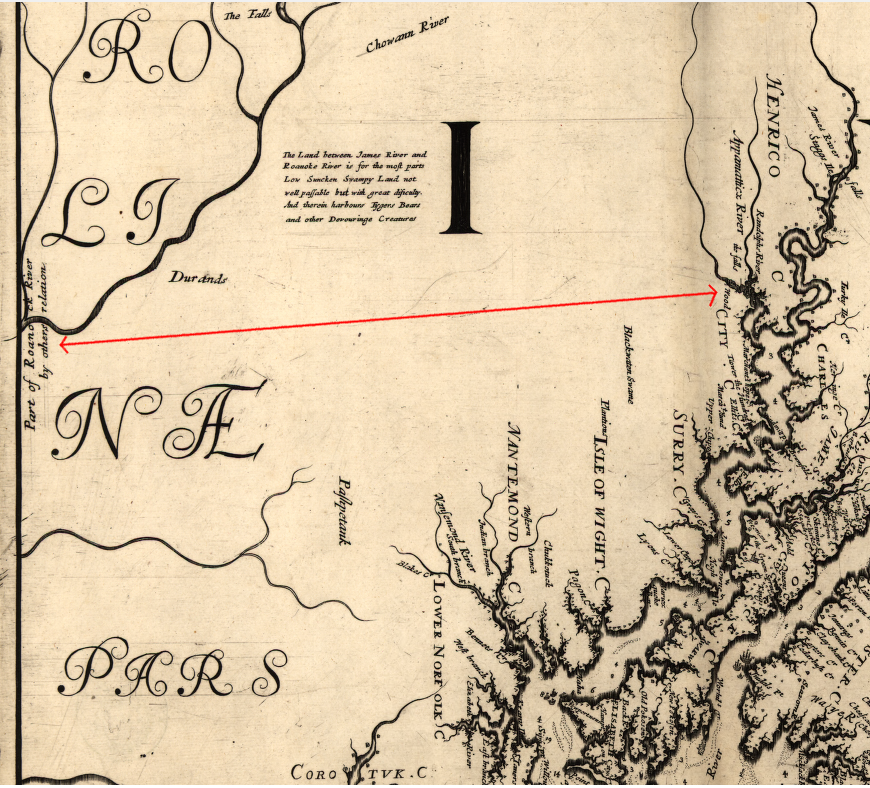

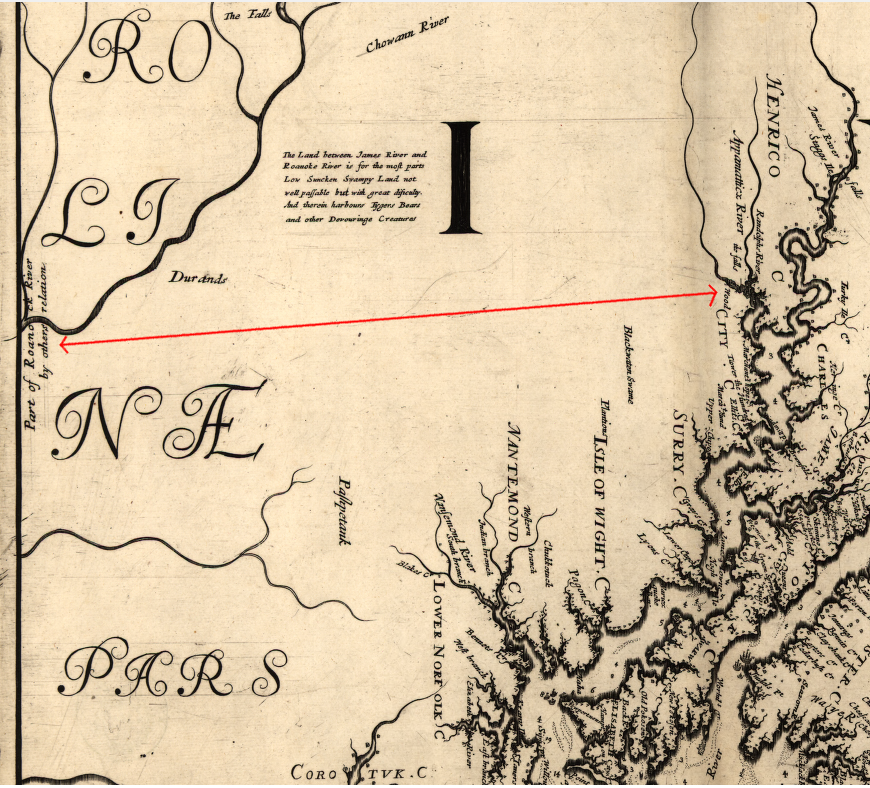

Augustine Herrrman's 1670 map (oriented with north to the right, and the Carolina/Virginia border on the left) shows almost no information for the territory between Abraham Wood's fort at the falls of the Appamattox River and the Roanoke River to the south

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 (by Augustine Herrman, 1670)

When Wood, Bland, and the others reached their first Nottoway town, the residents were caught by surprise. One of Edward Bland's servants shouted and the Nottoway ran away, causing Bland to name the site "Farmer's Chase." After the occupants returned, the expedition obtained the services of Oyeocker (an Iroquoian-speaking Nottoway) as a guide.6

At the Roanoke River they observed the falls where Native Americans caught migrating sturgeon, noting the surrounding area was "exceeding rich Land." They met various Native Americans on the trip, but were not clear who was authentic vs. misrepresenting themselves.7

The journal written by Edward Bland provides directions and distances from Fort Henry to the Roanoke River and back, but does not identify a defintive route. Because he described a "South westerne Discovery" and reached a river running to the west, some have suggested the group traveled all the way across the Blue Ridge to the New River.

A more common assumption of historians is that the traders took the Occaneechee Path to the trading town on an island, now underwater in the John H. Kerr Reservoir/Buggs Island Lake near modern Clarksville. There, Piedmont hunters and Cherokees from west of the Blue Ridge exchanged goods with traders from the Coastal Plain.

the Occaneechee Path was developed by traders before the colonies of Virginia and Carolina were created by kings in far-away London

Source: North Carolina State Archives, A New Description of Carolina (1676 - map oriented with north to the right)

When the English colonists arrived, they used the same location to do business. Previous traders from the Coastal Plain had brought marine shells to exchange at Occaneechee. Risk-taking colonial explorers (and various Native Americans who partnered with them) purchased deerskins and furs with prestige goods such as shiny glass beads, guns, metal tools, cloth, and other items that were not manufactured by Native Americans.

After examining the landscape of southeastern Virginia, Alan V. Briceland concluded that the expedition did not go west towards the New River or to Occaneechee. Initially, the expedition traveled southeast from Fort Henry along the Blackwater River. They turned south, crossing the Nottoway and Meherrin rivers to reach the Fall Line on the Roanoke River at modern day Weldon or Roanoke Rapids, over 50 miles east of Occaneechee:8

- His line of exploration was southwest not of Fort Henry, but of Virginia - that is, southwest of the center of settlement, of the center of government, and

incidently, southwest of Bland's home on Upper Chippokes Creek.

traveling from Fort Henry first towards the Blackwater River, before turning south to meet the Tuscarora at the Fall Line of the Roanoke River, would have allowed Edward Bland to explore the territory near his land on Upper Chippokes Creek

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Edward Bland died just two years after the 1650 expedition, and the name "Blandina River" did not replace "Roanoke River" in common use. After Edward Bland died, his younger brother Theodoric Bland came to Virginia to mange the family's property and business interests. Theodoric Bland and his descendants became key leaders of the gentry, and the Blands became one of the "First Families of Virginia" (FFV's).

Abraham Wood sent other expeditions into the backcountry from Fort Henry. In 1671, he sponsored the trip of Thomas Batts and William Fallam across the Blue Ridge. Batts and Fallam discovered a river flowing to the west and named it Wood River, though today it is known as the New River. Fort Henry was also known at times as Fort Wood, but today the community there is known as Petersburg. It is named not after Abraham Wood but after his son-in-law, Peter Jones.9

the Blandina River is known today as the Roanoke River, and the Wood River is known as the New River

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the British and French dominions in North America by John Mitchell (1755)

Links

- Archive.org

- Carolana.org

- Native Heritage Project blog

- NCPedia

References

1. William Waller Hening, "Acts of Assembly, March 1645-6 thru October 1646," Hening's Statutes at Large, p.315 http://vagenweb.org/hening/vol01-13.htm (last checked December 1, 2015)

2. William Waller Hening, "Acts of Assembly, March 1645-6 thru October 1646," Hening's Statutes at Large, p.326 http://vagenweb.org/hening/vol01-13.htm (last checked December 2, 2015)

3. Edward Bland, The Discovery of New Brittaine, reprint of the London edition by J. Sabin and sons, 1873, p.21, https://archive.org/details/discoveryofnewbr00blan (last checked December 5, 2015)

4. Edward Bland, The Discovery of New Brittaine, reprint of the London edition by J. Sabin and sons, 1873, p.15, https://archive.org/details/discoveryofnewbr00blan (last checked December 6, 2015)

5. Martha W. McCartney, "Narrative History," in Danielle Moretti-Langholtz, A Study of Virginia Indians and Jamestown: The First Century, National Park Service, 2005, http://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/jame1/moretti-langholtz/chap4.htm (last checked December 6, 2015)

6. Edward Bland, The Discovery of New Brittaine, reprint of the London edition by J. Sabin and sons, 1873, pp.1-2, https://archive.org/details/discoveryofnewbr00blan (last checked December 2, 2015)

7. Edward Bland, The Discovery of New Brittaine, reprint of the London edition by J. Sabin and sons, 1873, p.10, p.12, p.14, https://archive.org/details/discoveryofnewbr00blan (last checked December 6, 2015)

8. Alan V. Briceland, "The Search for Edward Bland's New Britain," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 87 Number 2 (April, 1979), pp.136, p.157, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4248294; "Bland Expedition," NCPedia, http://ncpedia.org/bland-expedition (last checked December 6, 2015)

9. "Jones of Petersburg," The William and Mary Quarterly, Volume 19 Number 4 (April, 1911), p.287, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1919429 (last checked December 6, 2015)

Exploring Land, Settling Frontiers

Virginia Places