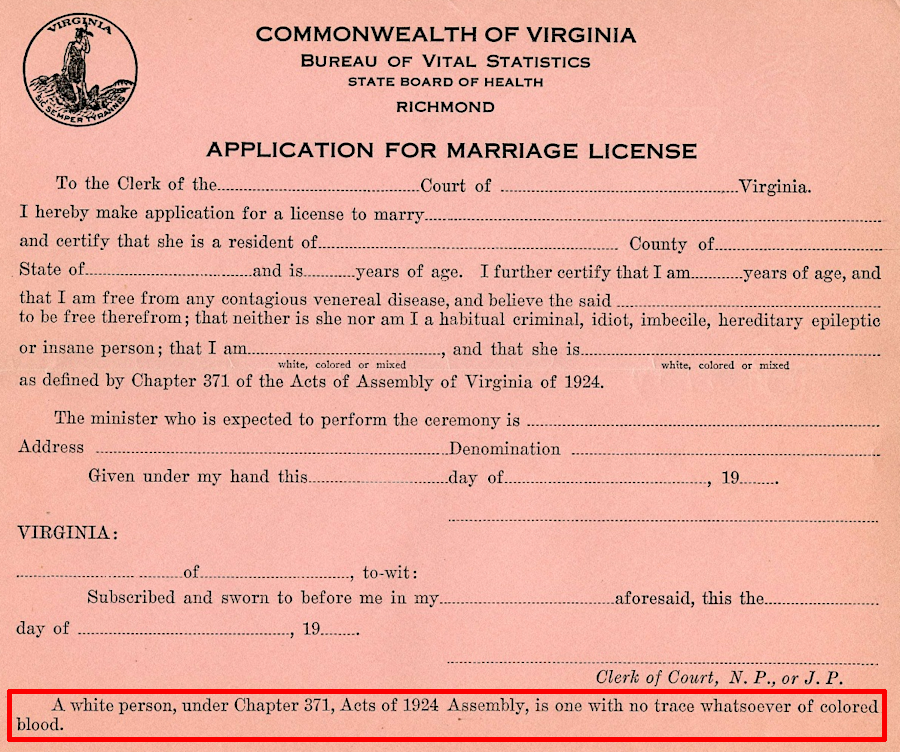

Virginia marriage licenses once required that white people have no trace of "colored blood"

Source: Library of Virginia, Who Do You Love?: Race And Marriage In Virginia Before The Loving Decision

Virginia marriage licenses once required that white people have no trace of "colored blood"

Source: Library of Virginia, Who Do You Love?: Race And Marriage In Virginia Before The Loving Decision

Colonial Virginia officials decided in the 1600's that black men and women imported from Africa and the Caribbean were to be treated as slaves and denied basic human rights. That included banning marriages with white people. The anti-miscegenation barriers did not ban white males from having children with enslaved women, and it was common for the white men to treat those children as property with just occasional slight privileges.

Before the Civil War, the state legislature did even consider marriages of free blacks to be worth documenting. The 1851 state constitution included (emphasis added):1

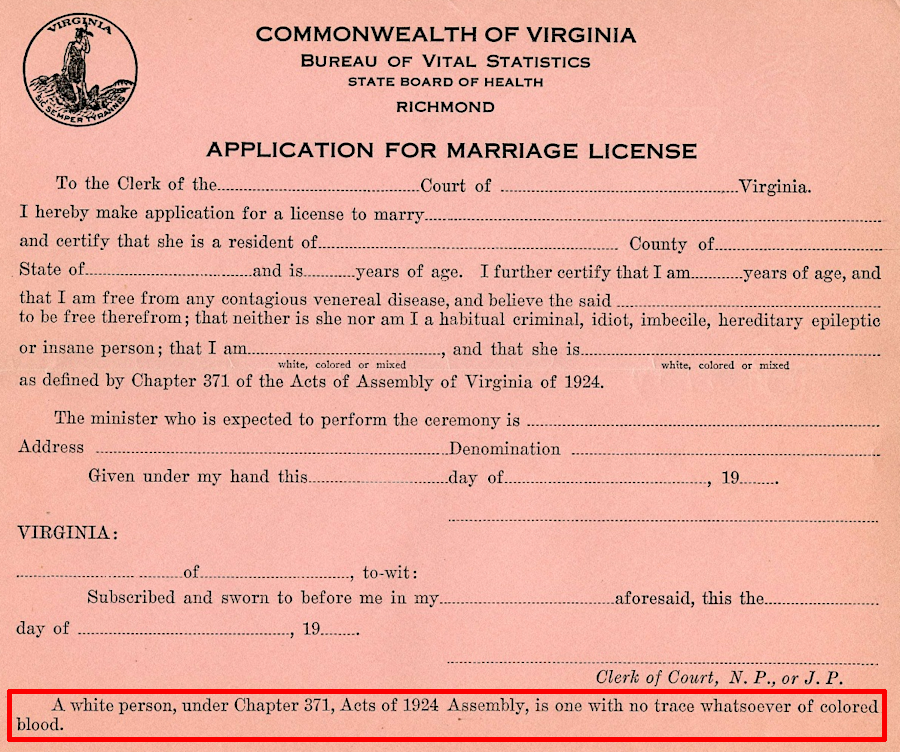

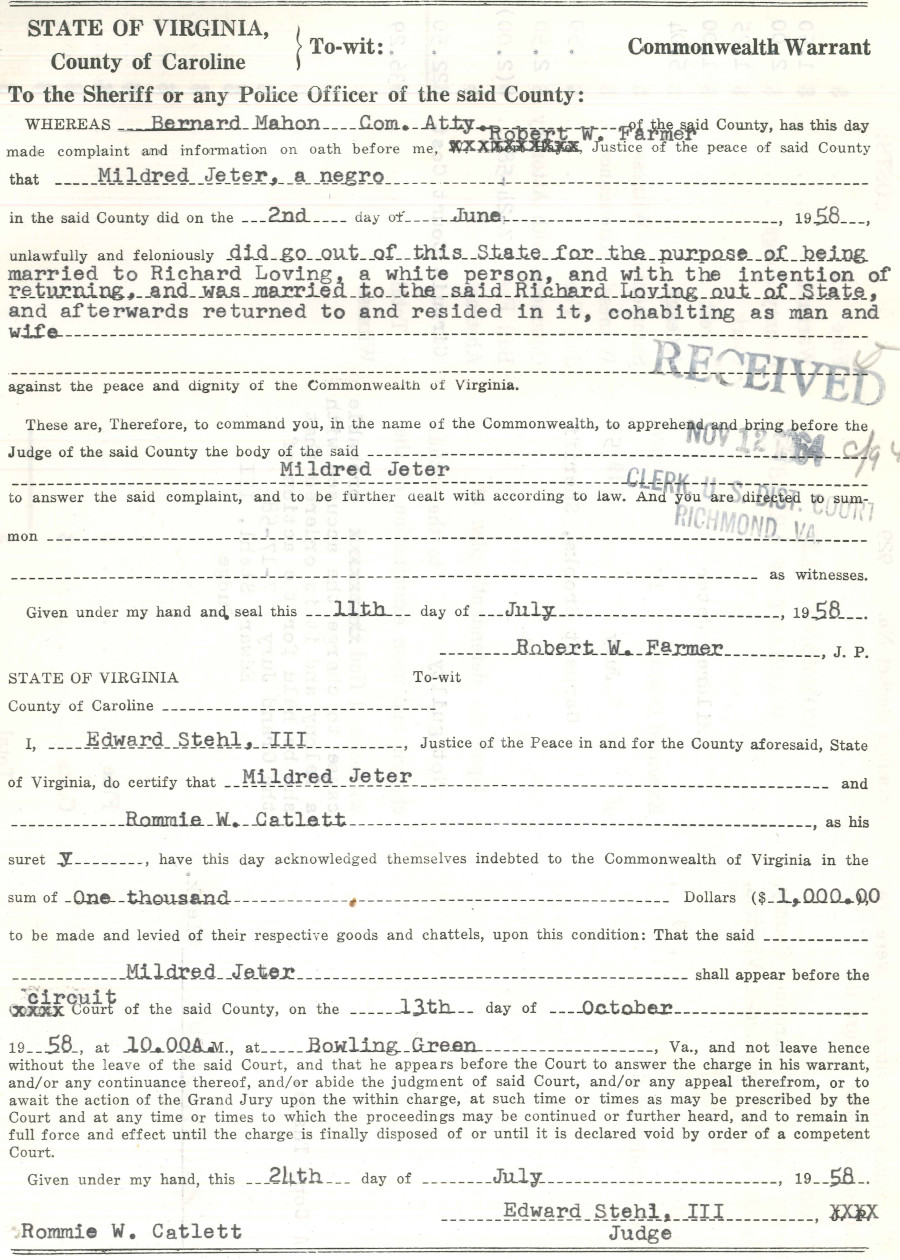

That ban on interracial marriage lasted until 1967. Richard Loving and Mildred Loving had been forced by a Caroline County judge to move out of the state, because he was white and she was "part Negro and part Indian." The county sheriff raided their home five weeks after the marriage. In a plea deal that avoided jail time, they pled guilty to violating the Racial Integrity Act and agreed to leave the state.

Virginia did not recognize the marriage of the Lovings in 1958, leading to a 1967 Supreme Court decision that legalized interracial marriage in all states

Source: National Archives, Marriage License for Richard Perry Loving and Mildred Delores Jeter

After five years in Washington, DC, they slipped back into Caroline County to be with each other and with their family. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) provided lawyers that requested the judge reconsider his earlier decision, but he responded:2

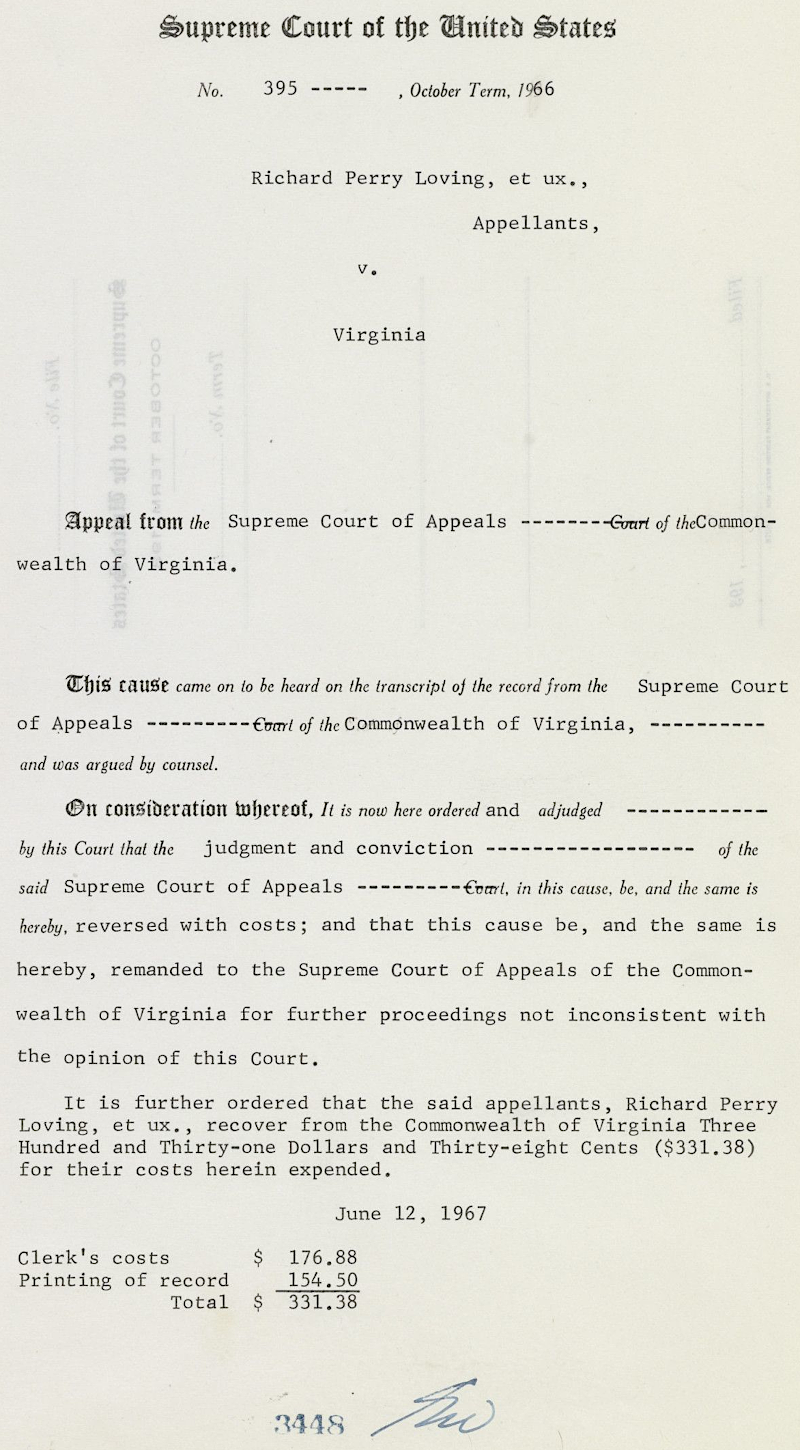

The case was appealed to the US Supreme Court. In 1967, it ruled in Loving vs. Virginia that states could no longer bar marriage between members of different races. At the time, 17 states had some form of anti-miscegenation barriers.3

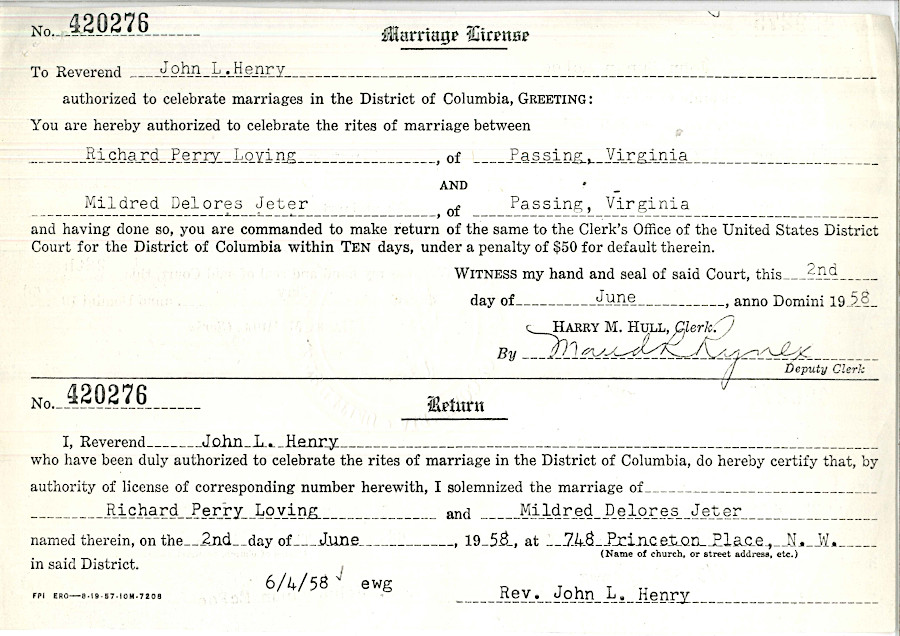

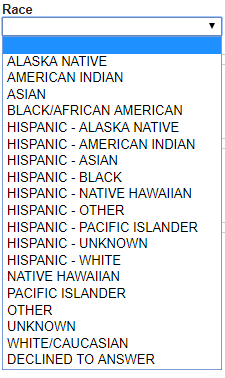

In 2019, three couples filed a Federal lawsuit claiming that the collection of racial data on Virginia marriage licenses, as mandated by state law, was unconstitutional. One applicant in Arlington County was of Asian Indian and Guyanese descent, and she rejected the option of selecting the "Other" box because none of the six pre-defined categories was appropriate for her heritage.

the choice of "Other" was offered in Arlington County for racial identify, for those not happy with the six predefined options

Source: Arlington County Clerk of Circuit Court, Marriage Application

Each county has its own marriage license form, and in Rockbridge County there were 200 choices. They included Aryan, Mulatto, Quadroon, Octoroon, Nubian, Gypsy, Cosmopolitan, Phoenician, and Moor. After the lawsuit was filed, the form was quickly revised to offer 19 choices.

the revised form for Rockbridge County marriage licenses

Source: Rockbridge County, Marriage Application

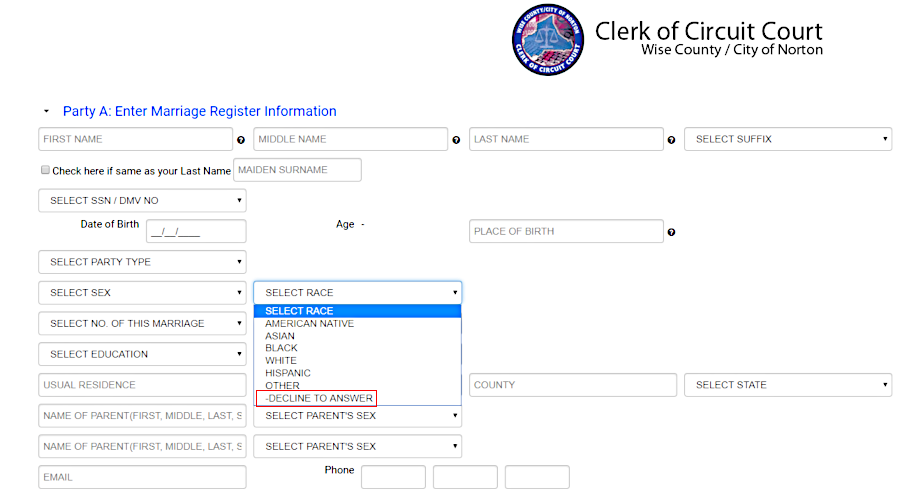

The Virginia Attorney General issued an opinion that the space on marriage license to identify an applicant's race could be left blank, and court clerks could issue a license without collecting racial data. The Attorney General could not change the state law which required completing the application, but chose to interpret the law to define which marriage licenses would be considered legally sufficient. He noted:4

the option to "Decline to Answer" regarding racial identity was authorized by an Attorney's General opinion in 2019

Source: Wise County/Norton Clerk of Circuit Court, Marriage Application

The lawsuit continued after the Attorney General issued his interpretation of the law. The Attorney General defended the legality of the requirement to identify one's race on a marriage license, while saying that it would have no effect so long as he was in office.

The Federal judge declined to accept that assurance as sufficient. He ruled that the state law was an unconstitutional violation of the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution. In his opinion, he highlighted how the requirement was based on the 1924 Racial Integrity Act and the efforts of the registrar of Virginia's Bureau of Vital Statistics, Dr. William Plecker, to classify those with "one drop" of African-American blood as "colored."

The judge wrote:5

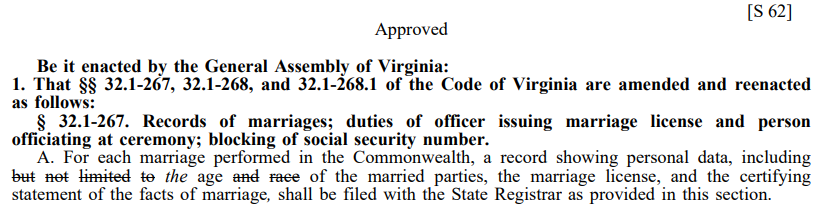

The 2020 General Assembly changed the law to eliminate the requirement that the race of married parties be included in marriage records, divorce reports, and annulment reports. That same year, Governor Ralph Northam ordered flags to be flown at half-mast after the death of one of the two main lawyers who had won the Loving v. Virginia case in 1967. Bernard Cohen had also represented Alexandria in the House of Delegates between 1980-1995. As a delegate, he succeeded in getting a right-to-die law passed but failed to get homosexuality decriminalized.6

In 2022, the US Congress passed the Respect for Marriage Act. The bill was triggered by the US Supreme Court reversing the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, which had prevented states from banning abortions for nearly 50 years. The Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization decision in 2022 included a suggestion that the 2015 ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, legalizing same-sex marriage, also could be reversed by the court. In response, a bipartisan majority inth US Coogress approved the Respect for Marriage Act, and that Federal law included a provision to ensure interracial marriages also would remain legal.7

in 2020, the General Assembly eliminated the requirement to identify the race of people on marriage certificates

Source: Virginia General Assembly, SB 62 (2020)

the sheriff of Caroline County arrested Mildred Jeter and Richard Loving in 1958

Source: National Archives, State of Virginia, County of Caroline Commonwealth Warrant of Arrest vs. Mildred Jeter

the US Supreme Court ruled in 1967 that Richard and Mildred Loving could be married and live in Virginia, overturning one more Jim Crow law

Source: National Archives, Decision in Loving v. Virginia