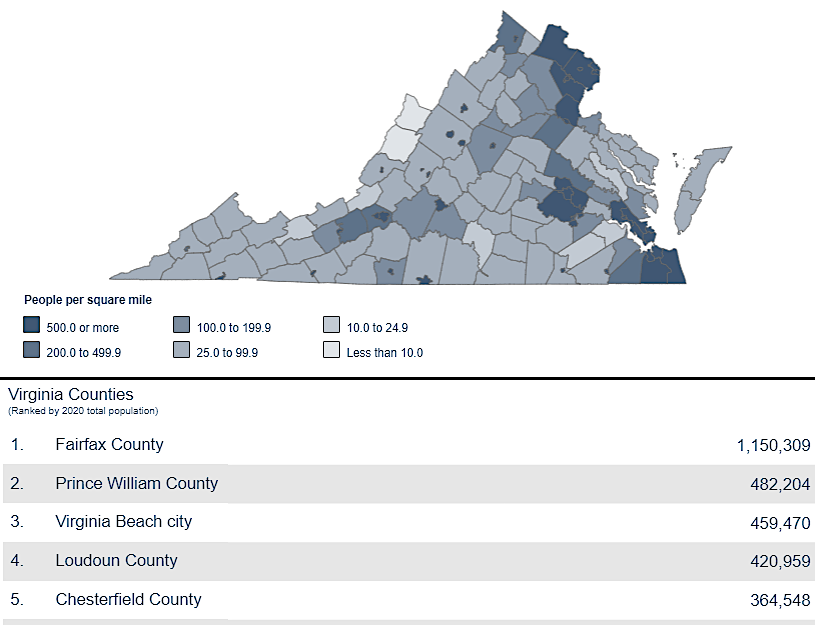

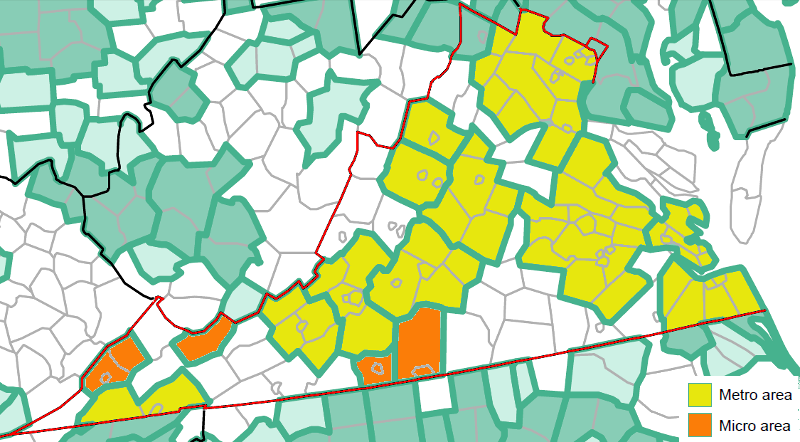

Virginia's population, in numbers and density, is concentrated in the "golden crescent" between Loudoun-Virginia Beach

Source: Bureau of Census, Virginia Adds More Than 600,000 People Since 2010

Virginia's population, in numbers and density, is concentrated in the "golden crescent" between Loudoun-Virginia Beach

Source: Bureau of Census, Virginia Adds More Than 600,000 People Since 2010

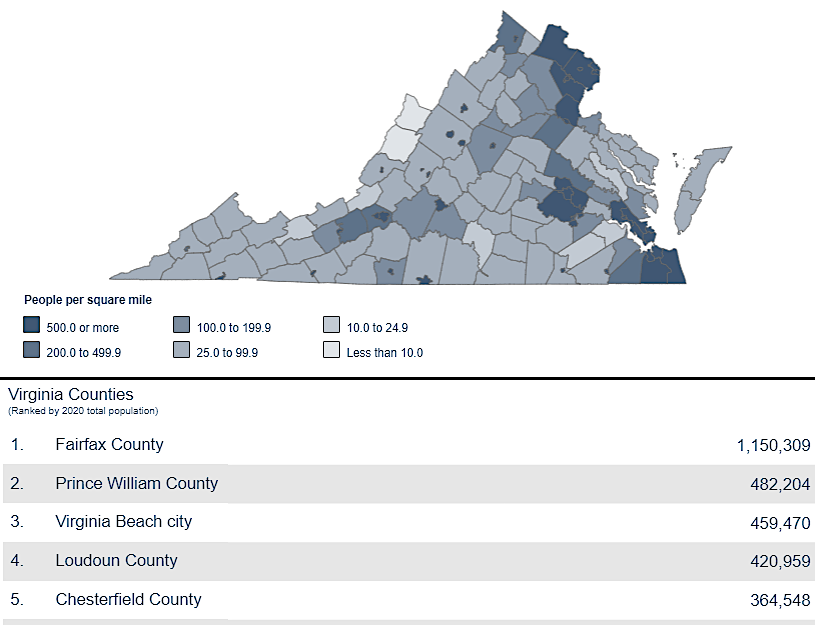

The City of Alexandria has more people per square mile than any other jurisdiction in Virginia, according to the Census in 2000 and 2010. There were over 128,000 people living within the 15 square miles of the city, for a population density of 8,452 people/square mile. In contrast, Highland County has the lowest density. Highland had only 6 people/square mile in 2000 - and lost population in the following decade.1

Virginia population density in 2010, by Census tracts

Source: Bureau of Census, 2010 Census: Virginia Profile

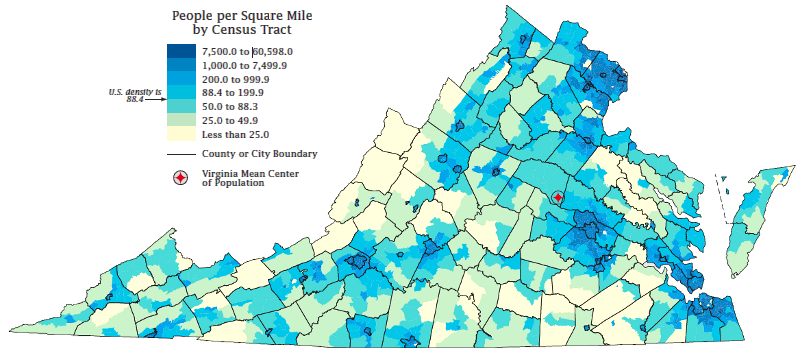

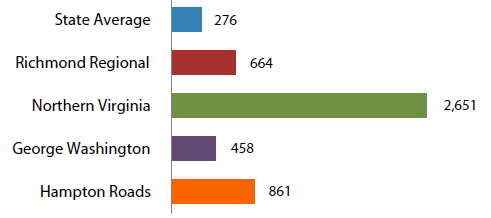

Virginia's population is concentrated in three urban areas that form a "golden crescent" from the Potomac River south to the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay.

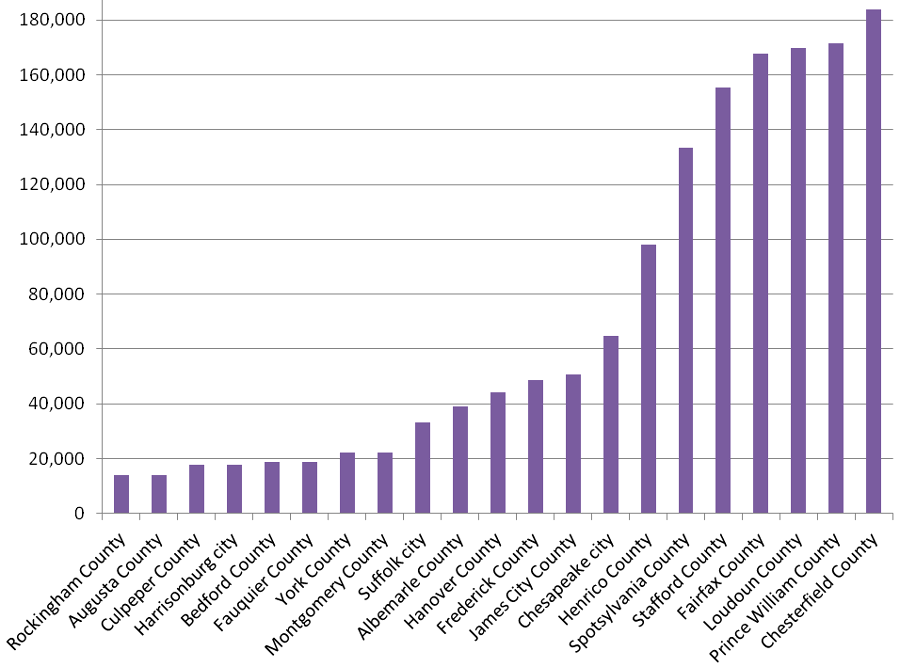

population growth in the 20 years between 2020-2040 will be greatest in the suburban fringe around the urban cores of Northern Virginia, Richmond, and Hampton Roads

Source: University of Virginia Weldon Cooper Center, Virginia Population Projections - Locality, Total Population

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) defines the boundaries of a Metropolitan Statistical Area (and the smaller equivalent, the Micropolitan Statistical Area) based on economic links. The 381 Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) in the US (plus 7 in Puerto Rico) are associated with at least one urbanized area that has a population of at least 50,000. A Micropolitan Statistical Area has an urbanized core with 10-50,000 people.

However, OMB includes rural/suburban jurisdictions that provide housing for commuters that work within the core urbanized area within a MSA. Metropolitan Statistical Area boundaries should not be considered urban vs. rural boundaries:2

In 2013, the Federal government adjusted the boundaries of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas. Virginia ended up with 11 Metropolitan Statistical Areas and 4 Micropolitan Statistical Areas:3

|

|

in 2013, the Federal Office of Management and Budget (OMB) defined boundaries for 11 Metropolitan Statistical Areas and 4 Micropolitan Statistical Areas in Virginia

Source: Bureau of Census, Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas (Feb. 2013)

While density is key to defining urbanized areas, there is no simple people/square mile statistical number that can be used to distinguish rural vs. urban areas. Boundaries of political jurisdictions can include some census tracts/blocks with a wide range of "census designated places" that might be rural or urban.

In the 2010 Census, 100% of housing units in Accomack County were located in "rural" areas/clusters and 99% of housing units in Fairfax County were in "urban" areas/clusters, but 49% of housing units in Pulaski County and 61% of housing units in Rockingham County were in "rural" areas.4

As suburbs expand around the periphery of urban areas in Fluvanna County (outside Charlottesville), Powhatan County (outside Richmond), and Stafford County (outside Washington), traffic congestion increases as new residents commute on 2-lane rural highways to get to jobs still clustered in the urban areas. Those highways were adequate for the traffic demands of a low-density population, but get overwhelmed when places known as Oak Hill Farm that raised cattle are converted into 400-house subdivisions (still called Oak Hill Farm, in many cases...).

Local political issues in such areas are dominated by demands to Fix The Traffic Problem, Reduce School Overcrowding, and Save The Rural Area, offering a dramatic contrast to the political issues debated in the US Congress that dominate cable news and talk radio. There is one overlap between local and national issues: real estate taxes often climb as property values climb, so groups that advocate for lower taxes (such as the Virginia Beach Taxpayer Alliance) often emerge in areas experiencing rapid growth.

Population density is more than just a statistical number, or the basis for distributing Federal grants. Density is also a key part of the decision process on where to locate new transportation infrastructure. In Virginia, state officials make key decisions on where to expand roads and transit capacity because the state controls most funding for such construction, but local officials also shape where new development is supposed to occur through land use planning decisions.

Virginia population density (measured in people/square mile) is projected to increase

primarily in Northern Virginia, Richmond, and Hampton Roads by 2035

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation VTRANS2035 Population Forecast (Figure 6)

Rural areas that experience rapid growth on the edge of urban centers become bedroom communities, exported workers to jurisdictions closer to the urban core. The local governments with new bedroom communities have to build schools, fire/police stations, ballfields, libraries, and other public infrastructure to meet expectations of the new residents.

In some cases, such as the gated communities of Heritage Hunt and Dominion Valley on Route 15 in western Prince William County, the values of the new houses may be high enough to generate enough property tax revenue offset the cost of the new services. In most areas, however, the low cost of housing is the primary attraction of new suburban developments located far from jobs. People are willing to commute from Culpeper to Arlington, or Stafford to Tysons, because they can buy a larger home in the suburbs.

Suburbanizing counties are rarely prepared to deal with the pressures to rezone farms/forests to become new suburbs. County officials have the legal authority through the local zoning ordinances to shape the pattern of growth, steering new housing to areas where new schools, roads, and other public facilities are being built. However, the decisions on where new housing will be located on the periphery of urban areas in Virginia are rarely shaped by county plans. Instead, county supervisors in Virginia typically rezone large swaths for development, rather than carefully release land for new housing with synchronized completion of adequate public facilities.

Individual landowners sell parcels to developers, and the developers determine which parcels will be converted into housing. Long-range plans and zoning ordinances are revised based on specific requests of landowners and developers. Parcels can be rezoned upon request, with or without support from neighbors who had anticipated future development based on existing county plans.

After 40 years of suburban growth, most rural properties are transformed into subdivisions. Arlington suburbanized between 1930-1960, Fairfax between 1950-1990, and now Loudoun, Prince William, and Stafford are going through similar cycles. During the decades of growth, new subdivisions are scattered across the landscape rather than concentrated.

Competing developers buy low-cost land, calculate the demand for housing, then make a profit from building as many houses on a parcel as zoning will allow. At times, pressure to increase zoning density and allowing more houses results in corruption. In 1966, three elected officials and eight developers in Fairfax County were convicted of bribery and conspiracy related to rezoning approvals.5

In areas of Virginia first experiencing rapid population growth, county land use plans can be "trailing" rather than "leading" indicators of where growth will occur. In Prince William County, for example, the Long Range Comprehensive Plan is supposed to identify the pattern of new development over the next 20 years. However, developers propose Comprehensive Plan Amendments every year. The county

Local government officials learn how to shape growth from experience, but at a cost. When the first set of commercial strip development and low-cost subdivisions begin to show their age, counties go through a phase of redevelopment. Typically, government agencies must incentivize redevelopment that will accommodate more people and increase tax revenue by funding transportation improvements.

That process is now underway in Fairfax County along the route of the Silver Line, and along the Orange Line near the Dunn Loring and Vienna Metro stations. Outlying counties such as Prince William and Stafford are anticipating that Virginia Railway Express (VRE) commuter rail stations can become nodes that attract transit-oriented redevelopment.

"Spotty" development creates disconnects between the location of new residents and the increased capacity of schools, roads, even sewage treatment plants. Inefficient, unsynchronized development of public infrastructure increases the cost, requiring higher taxes. "Smart growth" advocates propose minimizing the cost of new infrastructure, especially roads and schools (as well as fire stations, libraries, etc.) by coordinating growth of housing, co-locating jobs near housing, and providing bus/rail transit for commuters rather than expanding highways to support more numbers of cars with just the driver ("single occupancy vehicles").

"Smart growth" involves co-locating housing, retail, and jobs to minimize the need to expand highways, and to provide green spaces and recreational sites within walking distance of housing. While smart growth advocates call for developing a mix of housing types to offer choices to customers, concentrated high-density housing next to a transit facility (such as a Metrorail station) is often the centerpiece of smart growth developments.

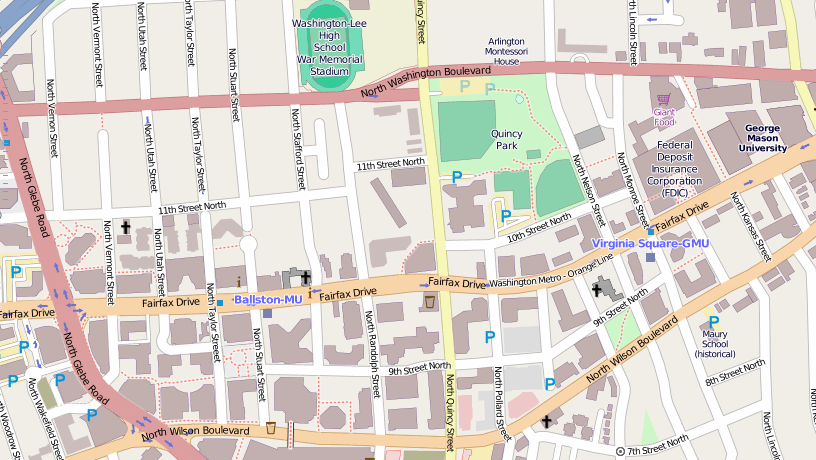

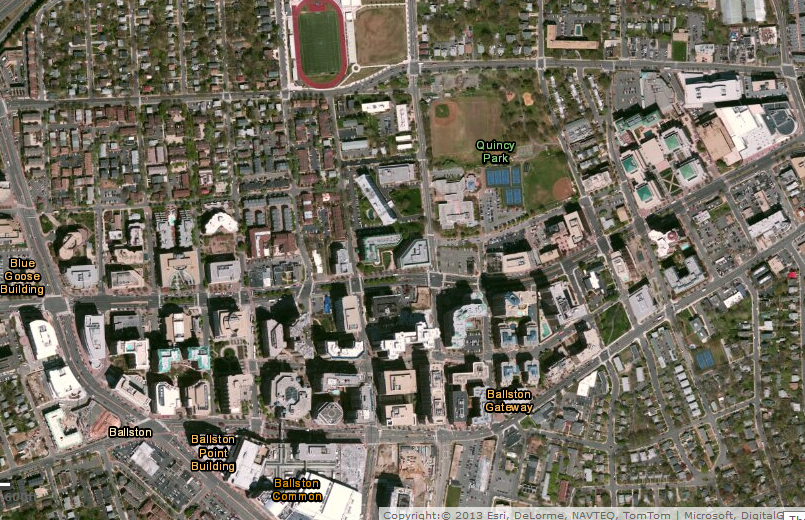

In Virginia, the showcase for smart growth is the Rosslyn-Ballston corridor in Arlington. That community emerged over 30 years, after county officials committed to redevelopment based on the extension of the Orange Line underneath Wilson/Fairfax boulevards rather than in the median strip of I-66.

VRE stations could become nodes for redevelopment in suburban counties

Ballston has been transformed over 30 years by high-density development, in a rare example where county plans determined in advance where new growth would occur

Source: ESRI ArcGIS Online (OpenStreetMap)

Arlington zoning concentrated development on commercially-zoned property within 1/4 mile of the Orange Line, so density of residential neighborhoods further away was not increased

Source: ESRI ArcGIS Online (ImageryWithLabels)

Cornell University has a definition for the alternative to smart growth:6

Key local and state decisions regarding growth patterns (where should we develop? at what density should we develop? what sort of uses - commercial, residential, office - should be authorized at various locations? what new roads should be sketched onto the map?) are made 5-15 years in advance of actual changes on the ground. When dirt is turned and local residents discover a field/forest is being converted to another use, they are usually too late to force any changes in the decisions.

In addition, the ability of average citizens to shape the decision process is limited by technical land use/transportation planning concepts and language. For example, a lane-mile is one lane of highway, for one mile of distance. If an existing 2-lane road is expanded to a 4-lane road for 5 miles, then 10 new lane-miles (2 lanes of additional road x 5 miles of distance) will be built. Constructing a lane-mile today costs roughly $3-4 million, so adding 10 lane-miles could cost $30-$40 million.

The buzzwords for measuring congestion are Level of Service (LOS, pronounced el-oh-ess) standards. Traffic-free, clear road conditions equate to LOS A, while bumper-to-bumper traffic would be LOS F.

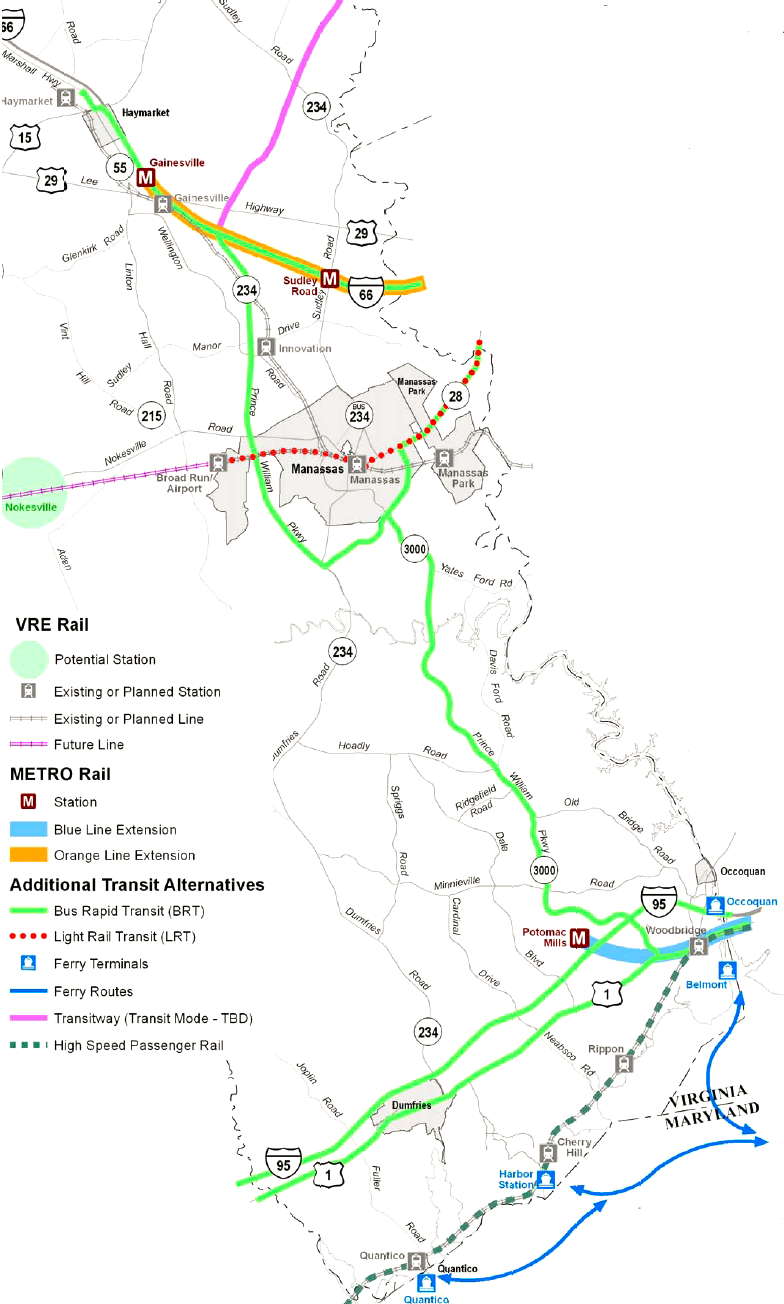

In Prince William County, the Comprehensive Plan seeks to maintain traffic congestion at LOS D. Aiming higher to LOS C to reduce congestion further would require building more lane-miles or interchanges. That can be extremely expensive. Just to maintain LOS D, Prince William County assumes construction of 700 new lane-miles by the year 2030, plus new extension of Metrorail Orange Line to Gainesville and Blue Line to Potomac Mills - and a new commuter ferry on the Potomac River to the District of Columbia.7

new transit infrastructure planned (but not funded...) in Prince William County by the year 2030

Source: Prince William County 2030 Comprehensive Plan, Map 3 - 2030 Transit Improvement Map

Costs to build new transportation capacity in just Prince William County to accommodate projected population growth, while maintaining the traditional suburban pattern where new residents move to the periphery of development and commute towards DC for jobs, exceed $4 billion. In addition, the community of Southbridge in southern Prince William County was not given that name by chance - an Eastern Potomac Crossing is proposed to connect rural Charles County, Maryland to the commuter routes in Virginia, extending suburbanization in that portion of Maryland. The replacement for the Woodrow Wilson Bridge, connecting Alexandria to Prince Georges County, cost $2.5 billion.8

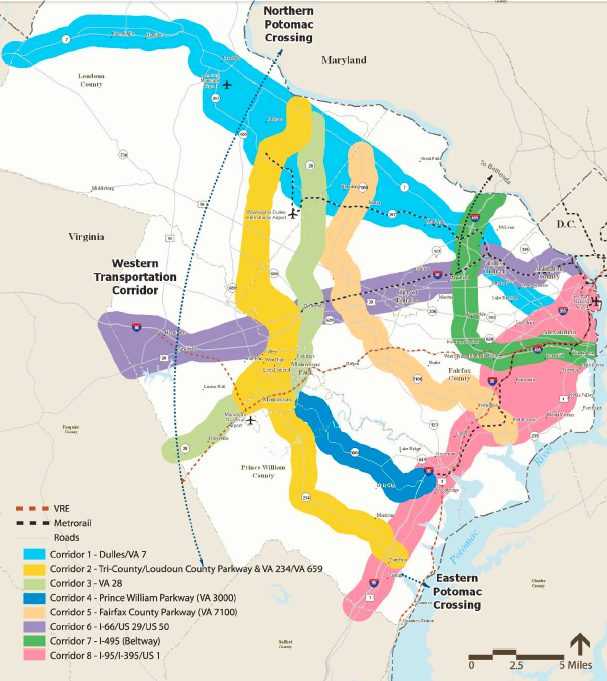

in the TransAction 2030 plan/wish-list of the Northern Virginia Transportation Authority,

new bridges would cross the Potomac River from Loudoun-Montgomery County and Prince William-Charles County

Source: TransAction 2030 Plan Projects

Low-density subdivisions in the suburbs transform the natural environment. Those concerned about environmental protection affect some decisions as an area suburbanizes, but environmental advocates have been unable to stop suburban sprawl in Virginia. However, low-tax advocates are potential allies of the environmental community regarding planning/zoning changes for new development. Building new lane-miles or transit systems to service low density subdivisions through 2030, as planned in suburban areas, will require new taxes as well as new tolls. Smart growth advocates anticipate that the cost of new infrastructure could trigger a shift in traditional transportation and land use planning, and open the possibility for more-effective alliances.

The face of opposition to the Bi-County Parkway in Loudoun and Prince William counties in 2013 were the three "Ladies of Pageland Lane." The political clout for the opposition to the project came from conservative Republican members of the General Assembly - who espoused the same talking points as the smart growth advocates in the region.9

The alternative to sprawl is not "no growth." Virginia's population continues to increase in Northern Virginia, Richmond area, and Hampton Roads. American society offers the freedom for people to move within the country, and private property owners have legal rights to develop their land as zoned. There is no way to lock the door and block people from moving to an area. Unlike some other states, Virginia does not have an "adequate public facilities" law permitting localities to delay new development by withholding building permits until sufficient schools, roads, and other public services have been constructed,.

In Virginia, the real opportunity is to shape where growth occurs, rather than to stop growth altogether. Increasing density in areas where new growth would impose less cost on taxpayers and the environment, and creating transit-oriented communities, is the key to the smart growth strategy.

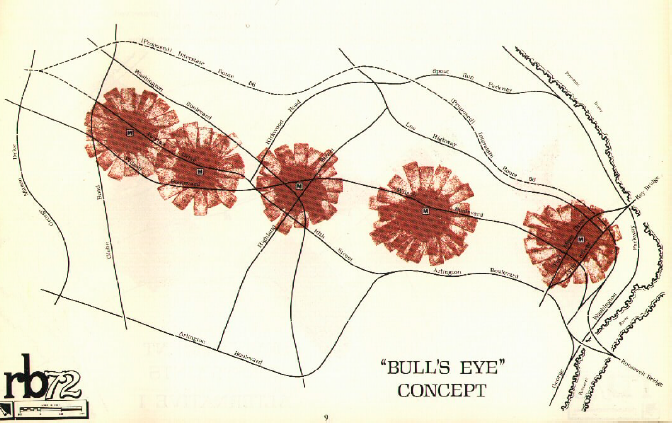

Rather than convert farms and fields to subdivisions, areas with low-density commercial buildings or outdated housing units could be redeveloped at higher densities to accommodate more people. Arlington County demonstrated how new transit can support high-density development in a bulls-eye within 1/4 mile of new Metro stations, while minimizing traffic congestion in the Rosslyn-Ballston corridor.

in Arlington County's revitalization of the Rosslyn-Ballston Corridor, new growth

was concentrated in high-density development within 1/4 mile of new Metro stations

Source: Arlington County - RB'72: Rosslyn-Ballston Corridor Alternative Land Use Patterns

Population growth can be accommodated by building up within the urban core, rather than out in suburbs spreading further and further from job centers. Fairfax County has made its greatest investment in revitalization at Tyson's Corner, creating a special tax district to help fund the Silver Line of Metro. The county is dramatically increasing planned density in Tysons, to incentivize developers to make Tysons a residential hub as well as a job center.

Transit can provide additional transportation services at less cost than constructing new roads, but population density must be great enough to provide a supply of customers that use public transit. Fairfax County hopes to mimic the Rosslyn-Ballston corridor success along Route 1 by changing zoning restrictions in the Richmond Highway Commercial Revitalization District, but new transit services may be limited to buses.

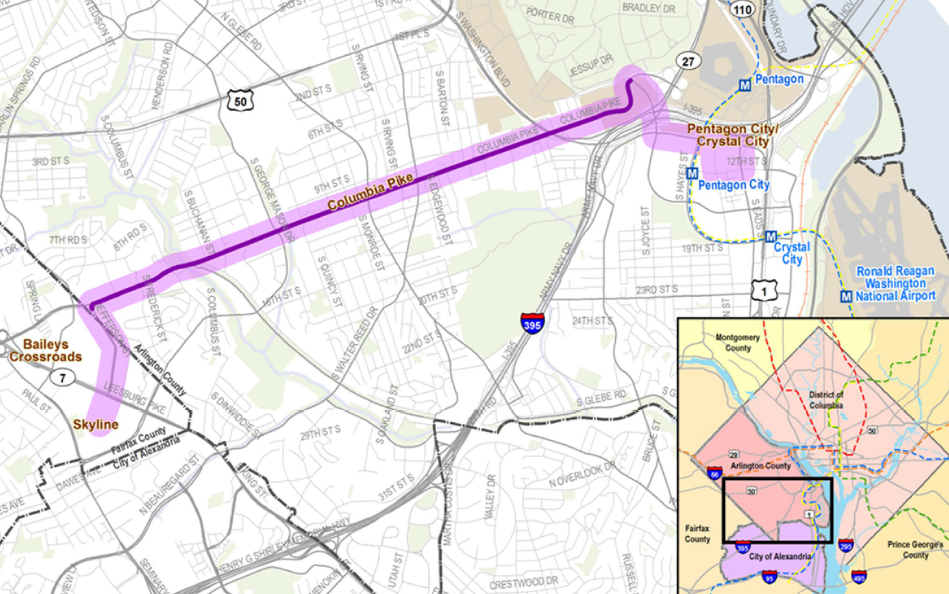

Along Columbia Pike, Fairfax and Arlington counties have committed to funding a new streetcar line, and simultaneously increasing density on that strip. Over the next 20 years (revitalization is a slow process...), multi-story mixed use buildings will replace 1-2 story buildings now lining Columbia Pike. Commercial offices and retail stores will be located on lower levels, with residential units on upper stories

Public investment in a streetcar line on Columbia Pike would not be cost-effective at current population levels - but those will change, according to the demographic estimates of the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments (MWCOG):10

Columbia Pike streetcar line will connect Skyline Towers and new development along Columbia Pike to Pentagon City Metro Station

Source: Columbia Pike Transit Initiative -

Return on Investment Study (July 2012)

In Virginia, Planning Commissions and elected officials have the power to steer population growth towards some areas and away from others. Long-Range Comprehensive Plans identify preferred land use changes over the next 20 years, while zoning ordinances control immediate development. Communities can implement Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) and Purchase of Development Rights (PDR) programs to shift growth away from rural areas, where new public infrastructure is relatively expensive.

By increasing population density in specific areas and limiting growth in others, fewer lane-miles of new roads would be required to move new commuters - or density might be increased to a level that justifies building new public transit, reducing traffic congestion on roads.

Some places in Virginia already have adequate public facilities for commuting. New housing being constructed in downtown Richmond, from Rockett's Landing upstream to the Fan District, will be within walking distance of many jobs. Extra buses on existing roads, or bike lanes, could eliminate the need for new roads. However, development east of Richmond in Henrico County will overload Route 5. Plans to convert a 2-lane rural road into a 4-lane commuter highway east to Pocahontas Parkway (Route 895) triggered Preservation Virginia to add the New Market Road Corridor to its list of "Most Endangered Historic Sites in Virginia" in 2012.11

New roads would not be required if new development was all concentrated within the boundaries of Richmond, or impacts of new roads could be minimized if new growth was located right at the city's edge. However, the elected officials in the County of Henrico have approved new residential subdivisions growth far from existing jobs.

Richmond and Henrico are separate jurisdictions, with separate elected officials and separate land use plans. Regional planning for transportation is based upon an assumption that the state of Virginia will fund new roads to accommodate new growth - Henrico taxes will not have to be increased to finance the expansion of roads to serve new residents located far from current job centers. As one Richmond columnist noted:12

Real estate agents in sprawling suburbs often note that retail follows rooftops - grocery stores, dry cleaners, and fast food restaurants are built once a community reaches a critical mass of population to shop at new stores. A Wegmans grocery store opened in Woodbridge in 2012, but only after enough new residents moved into the area along Route 1 in eastern Prince William County to create a new supply of customers.

Developers in eastern Henrico County are still making the assumption that roads will also follow rooftops. If enough voters move into an area, and if congestion on old roads becomes a clear disaster, then the Commonwealth Transportation Board will provide the funding to expand the road network - just as it has done since the 1932 Byrd Road Law.

However, the recent decline in gas tax revenues together with the increasing cost of maintenance of old roads/bridges threatens to bring an end to the traditional pattern. The Transportation Trust Fund, used to finance new construction, was at risk of drying up - with all revenues being directed towards maintenance and operations - until the General Assembly increased taxes in 2013.

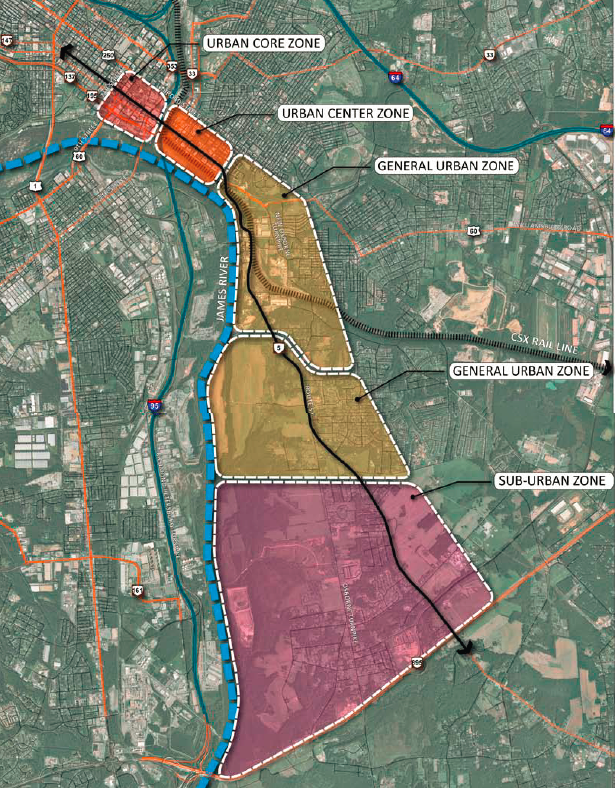

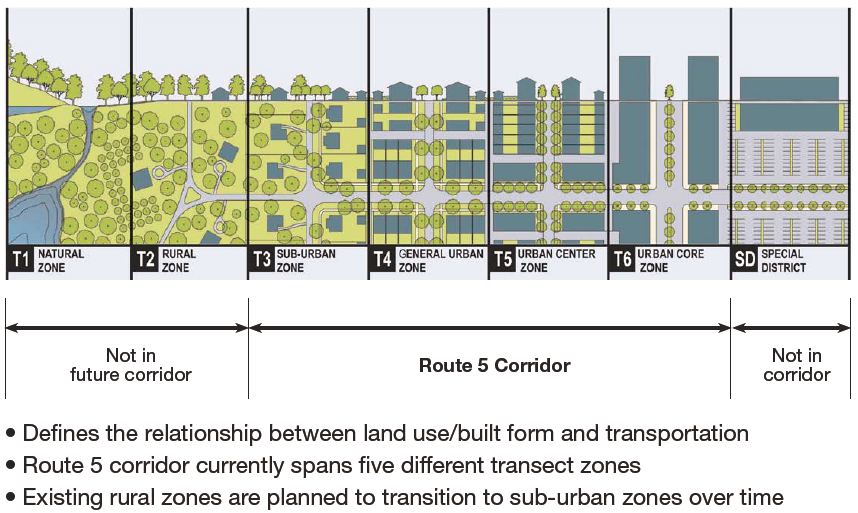

proposed transect zones between rural and urban areas southeast of Richmond, for planning the expansion of Route 5

Source: Route 5 Corridor Study - Map of Route 5 by Study Zones (Public Workshop #2 - Held May 31, 2011)

County/city officials can steer growth to high-density development zones that can be serviced by transit. New "bull's eyes" for rezoning to permit higher Floor-Area Ratios (FAR's) have been proposed around Silver Line stations. Fairfax County finally rezoned the land around the Vienna Metro Station to permit the MetroWest development, thirty years after Arlington County demonstrated that encouraging growth within walking distance (1/4 mile-1/2 mile) of a transit facility can minimize the impact of new residents on traffic congestion.

The Town of Herndon has committed to Transit Oriented Development (TOD) near the Herndon-Monroe Metro station. It has replanned the area in the town to stimulated developers to build large buildings next to the Metro station, anticipating that smart growth plans tied to the Silver Line transportation capacity can spur economic growth/increased population in Herndon without generating LOS F traffic congestion:13

plans for high-density, multi-story dwellings north of Herndon-Monroe Metro station, in Metrorail Station Urban Development Area

Source: Herndon Metro Station Area Study, Herndon Transit-Oriented Core Plan - Conceptual Massing (Figure ES.9)

Transit Oriented Development (TOD) focuses on high-density development, with tall buildings within walking distance of a rail/bus line. Funding for roads can be prioritized for improvements in areas where costs to provide adequate public facilities will be lower. In some cases, including Tysons Corner in Fairfax County and Town Center in Virginia Beach, new high-rise development can be planned to acquire sufficient population that justify building a mass transit rail system. Fairfax County business leaders are so optimistic about the impact of the Silver Line that they claim "Fairfax County is now the downtown. D.C. just became our suburb."

The flip side to planning for bulls eyes of dense development is that large rural areas can be planned/zoned for low-density development. Public investment in new infrastructure can be limited in rural, low-density areas.

However, defining a "urban growth boundary" with low-density development is politically challenging. Landowners often object that the economic potential of their property is being limited by government action. (The US Supreme Court ruled in 1926, in Village of Euclid, Ohio v. Ambler Realty Co., that zoning is a legitimate exercise of the "police power" of governments. Landowners are not entitled to compensation when some properties are zoned for low density, even though government action may reduce the value of the private property.)

Growth boundaries can be established when development pressure is low, but as population increases the difference in land values on either side of the line can spur a demand for replanning/rezoning.

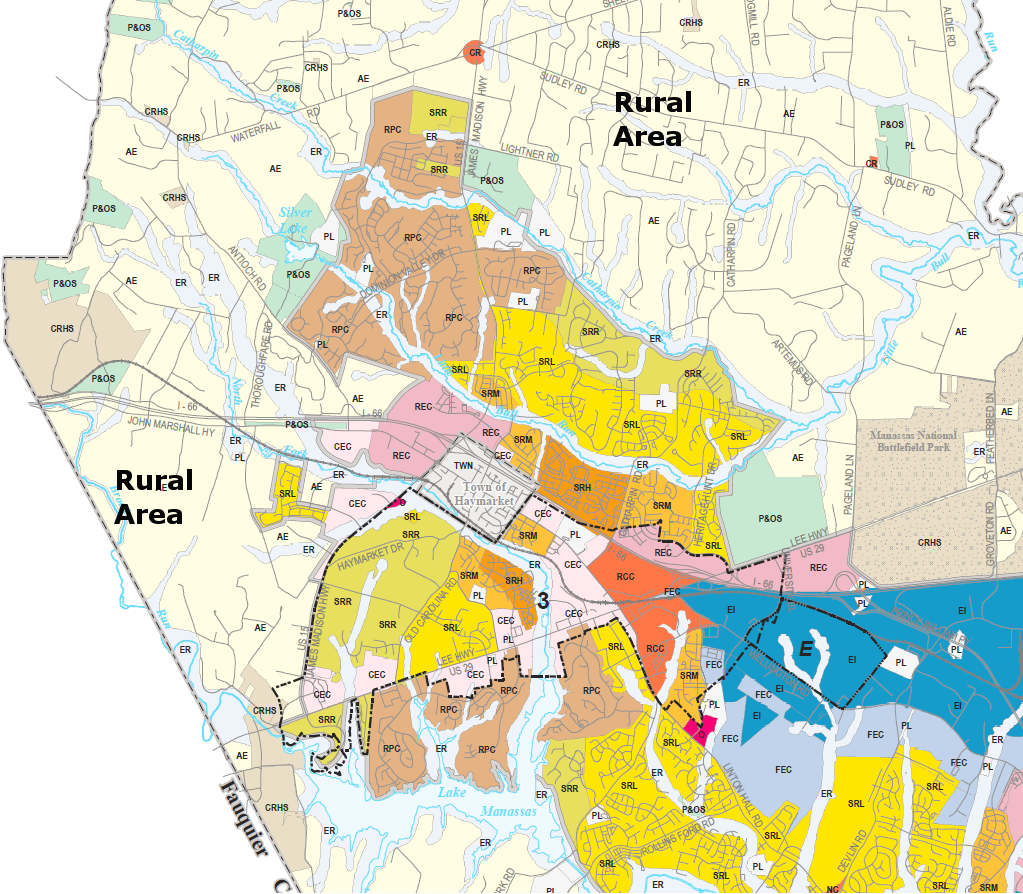

In Prince William County, a Rural Area has been steadily diminished in size whenever the Board of County Supervisors has revised the Comprehensive Plan. New plans to build a "road to Dulles," connecting Route 234 near Gainesville with Route 606 in Loudoun County, will trigger new pressure to rezone the land between Manassas National Battlefield Park and Route 15.

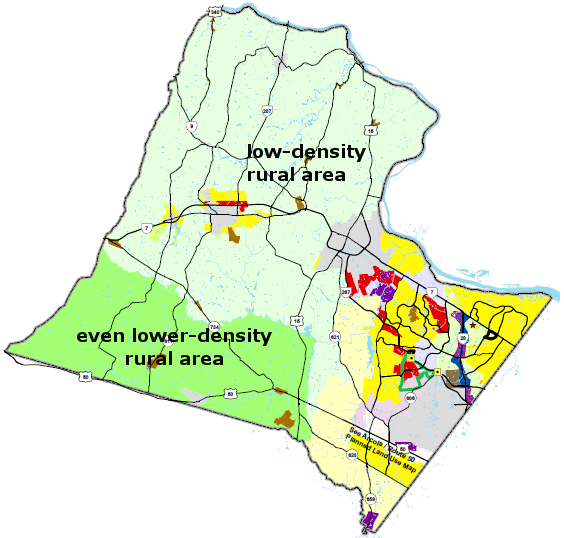

growth is supposed to be limited in the Rural Area of western Prince William County and encouraged in the Development Area,

Source: Prince William County ?Long Range Land Use Map

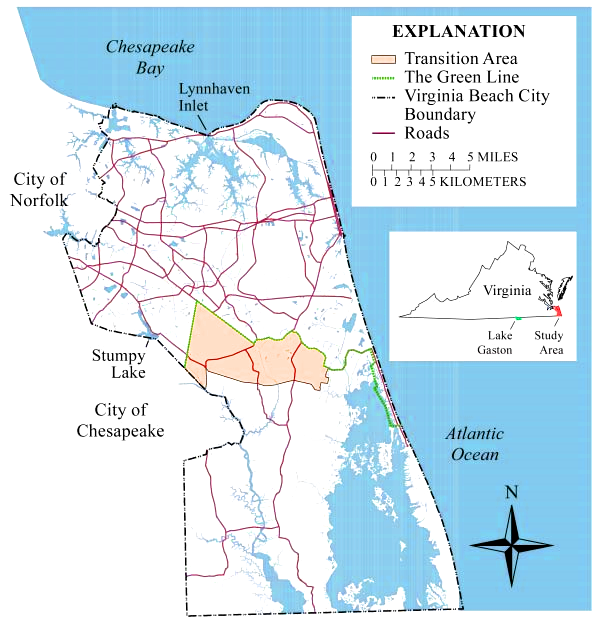

In 1963, Princess Anne County merged with the small City of Virginia Beach to create the modern City of Virginia Beach. It was a uniquely rural "city" at the time; it even issued hunting licenses. To preserve the existing commercial agriculture in the new city, a "Green Line" was drawn to limit development in the southern part of the city. Today, growth is directed towards the center of Virginia Beach, where east-west roads connect the oceanfront resort area with Norfolk and a freight rail line may be converted into an extension of Norfolk's light rail transit system (known as the Tide).

Transit Oriented Development (TOD) next to light rail in Norfolk, the "Tide"

Green Line and Transitional Area, as defined in Virginia Beach land use planning

Source: US Geological Survey, The Virginia Beach Shallow Ground-Water Study (USGS Fact Sheet 173-99)

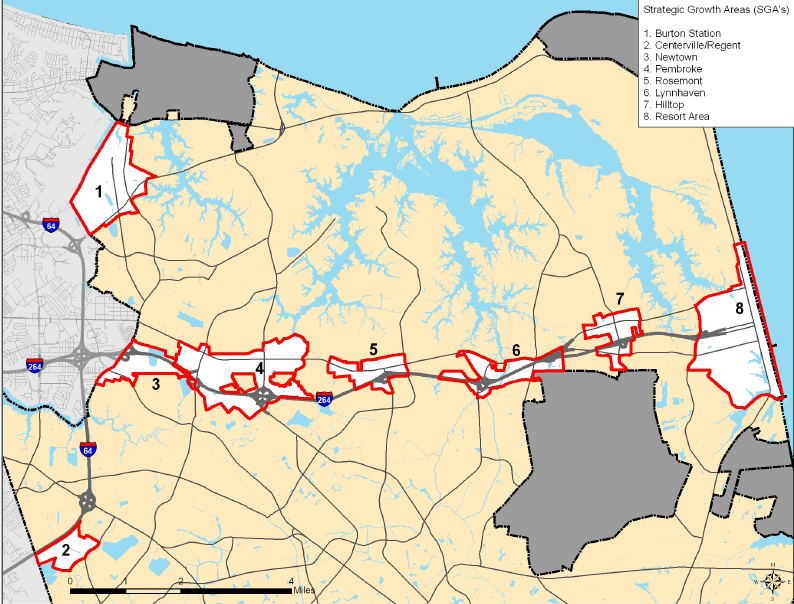

Strategic Growth Areas, where development is encouraged

Source: Virginia Beach 2009 Comprehensive Plan, Introduction

In Loudoun County, two-thirds of the land is planned as a Rural Area - though zoning in the rural farmland areas originally allowed one house to be built on three-acre lots. Now, funding for road improvements will be steered away from the Rural Area to the Suburban Area, and Loudoun will not seek to upgrade old dirt roads so they meet modern highway safety standards. The Loudoun County Comprehensive Plan makes clear how local officials can use land use planning to coordinate housing density and transportation funding, and how new roads spur new housing/new traffic congestion when zoning and road construction plans are not coordinated:

Loudoun County zoned for high-density development on eastern side of county near job centers

in Northern Virginia/DC, directing resources towards public infrastructure there rather than in rural area on western side

Source: Loudoun County Comprehensive Plan, Planned Land Use Map

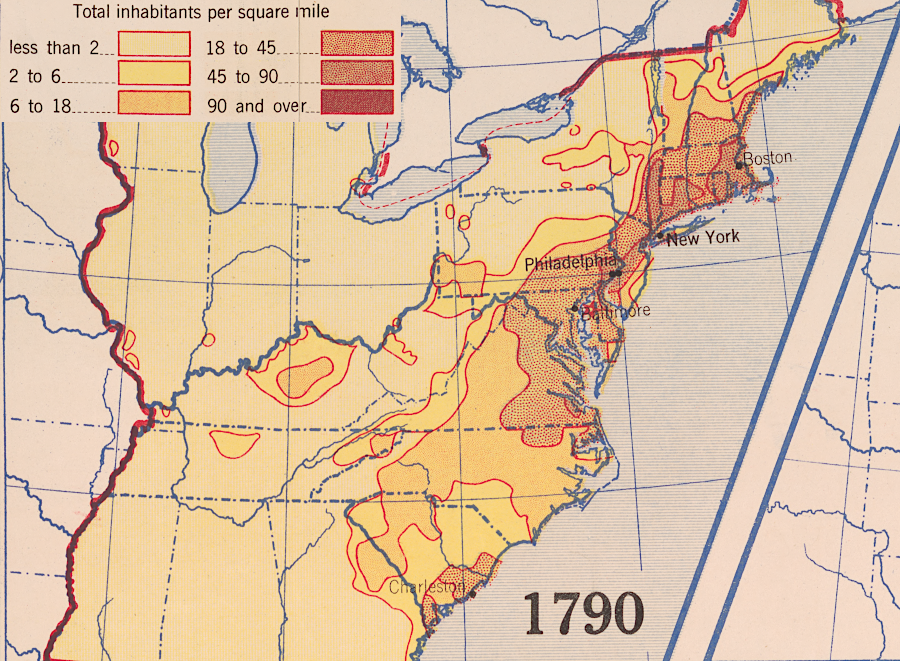

population density in 1790

Source: Library of Congress, Population density, 1790-1870 (Hart-Bolton American history maps, 1919)

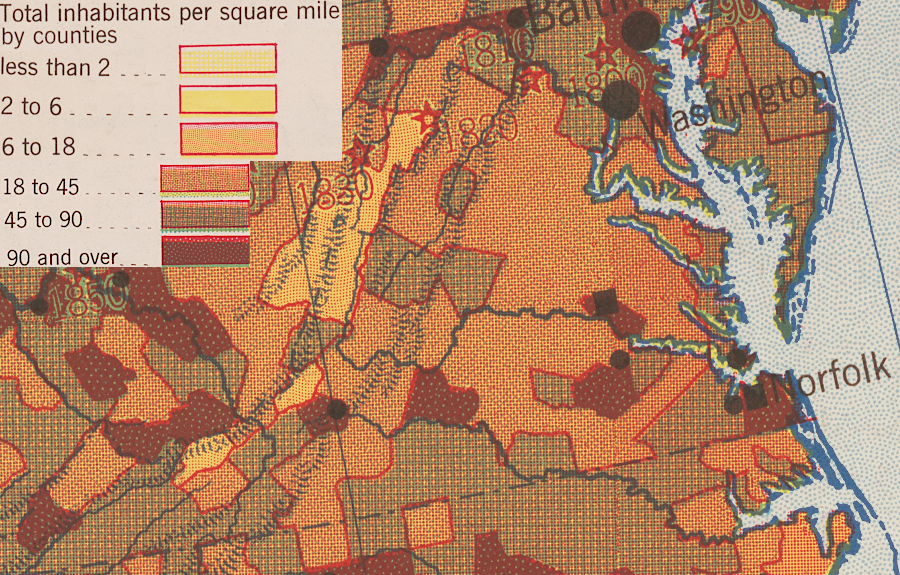

population density in 1920 (note Northern Virginia)

Source: Library of Congress, Population density, 1920 (Hart-Bolton American history maps, 1919)

population density in 2000

Source: Bureau of Census - 2000 Population Distribution in the United States map

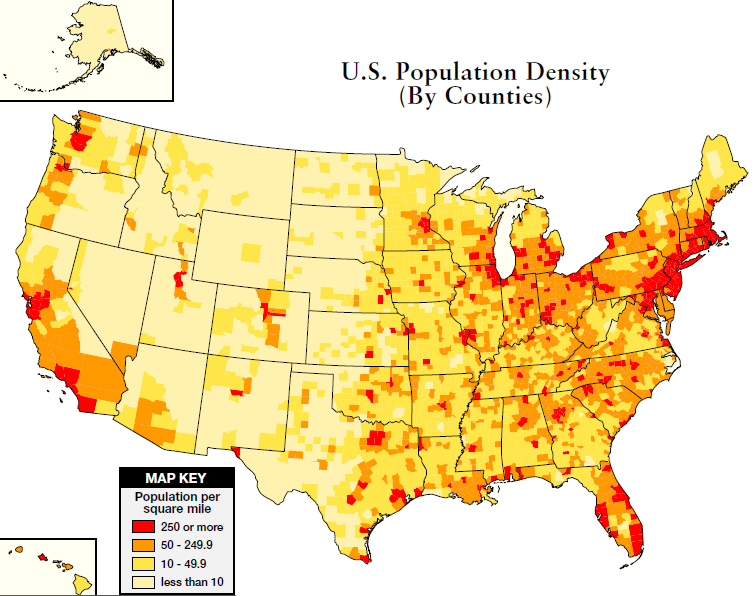

population density by counties in the United States

Source: Bureau of Census