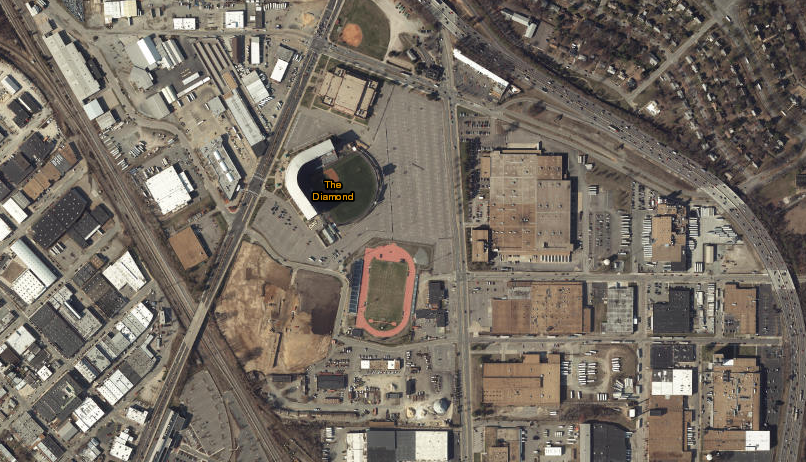

the AAA Richmond Braves baseball team moved to Gwinnett County, Georgia in 2009 when that community provided a newer ballpark than The Diamond, built in 1985

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the AAA Richmond Braves baseball team moved to Gwinnett County, Georgia in 2009 when that community provided a newer ballpark than The Diamond, built in 1985

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Schools and non-government organizations such as Little League offer nearly all Virginians a chance to play organized sports, such as football, soccer, even field hockey, lacrosse, and aquatics. Most ballfields are owned and operated by city/county park authorities or schools. In most areas, organized leagues pay fees and parents hold fundraisers to add amenities such as lights and concession stands. In urbanizing areas such as Northern Virginia, developers can occasionally be "induced" to proffer funding for facility upgrades, such as conversion of grass fields to all-season surfaces, in exchange for a rezoning approval.

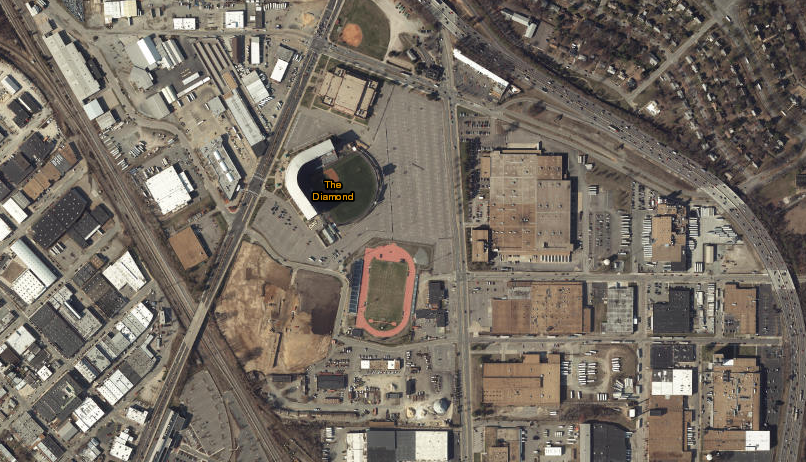

Rural areas also have sports facilities. The Virginia Horse Center in Rockbridge County, opened in 1988 near Lexington, has a 4,000-seat arena known as Anderson Coliseum. The center was originally funded as a partnership between the state and local organizations, and after the state pulled out in 1997 the Virginia Horse Center borrowed money from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA).1

Though small in size compared to the urban facilities, the tourism benefits of the horse center were substantial. A 2001 economic study concluded that at least 25% of customers at Lexington motels near the center were attending events there, and an update three years later indicated a 10% increase. A 2% occupancy tax on Lexington and Rockbridge County hotel customers helped the Virginia Horse Center pay back its USDA loan, but costs exceeded revenues. In 2014, the Virginia Horse Center asked the local governments to add an additional 1% to the transient occupancy tax.2

the Virginia Horse Center was located where land was inexpensive, horses were common - and I-65 and I-81 provided easy access from Maryland, Tennessee, and the Piedmont of Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

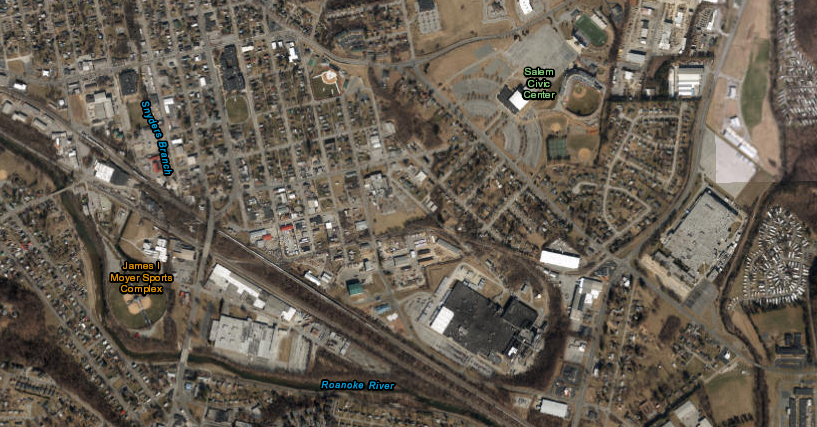

Professional sports require high-quality facilities for teams and spectators. Supporters of building new sports stadiums present them as economic development projects, justifying public funding to provide a tourism facility for a for-profit private business that will generate tax revenue offsetting the public costs. Public funds have been used to build arenas and coliseums in Hampton, Norfolk, Roanoke, and Richmond, and various universities have also built multiple use facilities that host concerts, college basketball tournaments, even tractor pulls.

The 2008-13 economic recession blocked Prince William's plans for subsidize a new ballpark for its AA baseball team, the Potomac Nationals. Art Silber, the owner of the team, then arranged for the Virginia Department of Transportation to build a commuter parking garage next to I-95 - and adjacent to the site of the new stadium built with private funding. A parking garage funded by the public can be used for evening and weekend ballgames, while the owner of the private baseball team did not have to purchase expensive land to provide parking at the stadium.

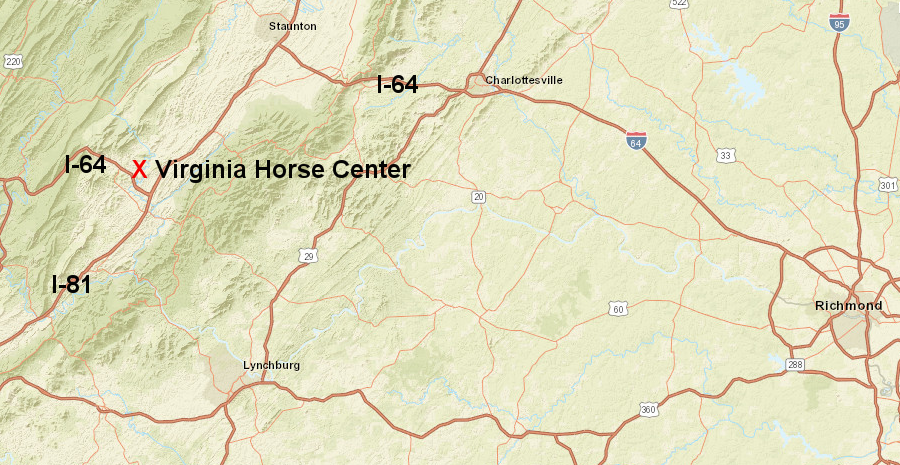

The City of Salem has been especially successful in building sports facilities that attract school and league tournaments, generating income in the local community as well as tax revenue to help fund the ballfields. The city invested in sports tourism, building infrastructure at city expense - the same way Norfolk invested in attracting cruise ship passengers.

Salem hosts national tournaments and championships for sports such as softball. The national audience may not be sufficient to generate television coverage, but Salem's hotels and restaurants get an economic boost when ball teams and their families/supporters stay overnight.

Salem constructed enough ballfields and sports-associated infrastructure to attract national tournaments

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In some cases, private investors have created sports complexes designed to generate a profit from league use and tournaments. The 250-acre SportsQuest complex in Chesterfield County was proposed in 2008 as a sports training and exhibition center, by a doctor who became wealthy dealing with sleep disorders and justified the complex as a way for people to "get healthy."

In some cases, private investors have created sports complexes designed to generate a profit from league use and tournaments. The 250-acre SportsQuest complex in Chesterfield County was proposed in 2008 as a sports training and exhibition center, by a doctor who became wealthy dealing with sleep disorders and justified the complex as a way for people to "get healthy."

The county viewed it as an economic development opportunity, with sports tournaments drawing overnight tourists and increasing local tax revenues. The facility was developed with a mix of public and private funds. Chesterfield County invested over $4 million to lease use of land at the site for a senior center, basketball court, and some public use of the lighted synthetic turf fields for the next 20 years.

The entire project was projected to cost up to $250 million:3

The finances involving "dues-paying members" ended up attracting oversight by the Virginia Attorney General after a promised fitness center was never constructed. By 2012, SportsQuest was bankrupt. The company that had loaned money for initial construction then took over the ballfields and managed rentals and tournaments. SportsQuest was renamed the River City Sportsplex and advertised as:

Chesterfield County bought the River City Sportsplex in 2016. The private facility was planning to raise fees for tournaments, but the county feared that fewer tournaments would attract fewer sports-oriented tourists. Chesterfield County also saw an opportunity to acquire recreational assets at a low cost, since the seller was willing to accept a price below the value assessed for property taxes.

The purchase was as much an investment in tourism as in expanding recreational opportunities for the growing suburban population. The Richmond Times-Dispatch noted in its story about the county's decision to buy the River City Sportsplex:4

the River City Sportsplex includes nine synthetic turf fields in one section and three in another, with parking between the two sections

Source: River City Sportsplex

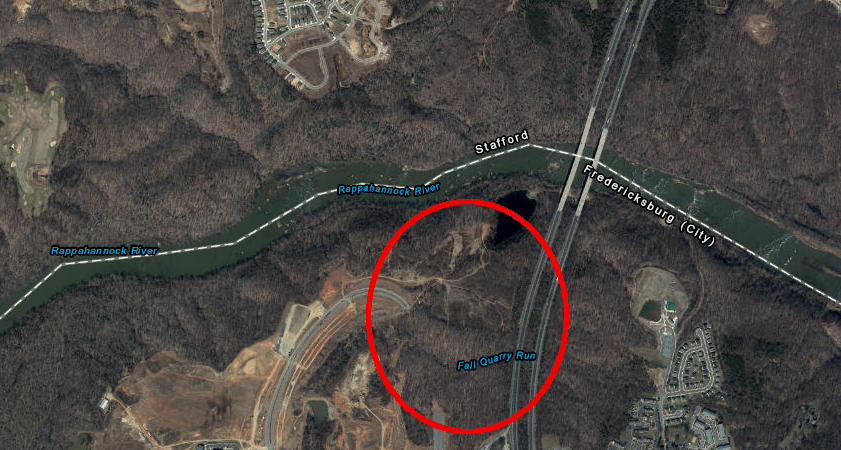

In the Fredericksburg area, the Silver Companies (the largest local developer) partnered with other companies in 2013 to build a new destination sports complex in Spotsylvania County. It was projected to attract one million visitors each year.

To provide entertainment, the former Hagerstown Suns, a Class A minor league baseball team, agreed to move from the suburbs of Maryland to the suburbs of Virginia. The possibility of using the stadium to recruit professional lacrosse and soccer teams, as well as hosting concerts and community events, was also noted.

The City of Fredericksburg supported building the ballpark, expecting it to spur completion of Silver's Celebrate Virginia South development north of the Central Park shopping center. Previous proposals to construct the Kalahari Resorts water park and the National Slavery Museum in Celebrate Virginia South had failed, and Fredericksburg was prepared to force the sale of some parcels to recover $1 million in overdue real estate taxes.

Building a 5,000-seat minor league baseball stadium shifted economic development hopes from a waterpark or historical museum to sports. The land originally intended for the National Slavery Museum was sold for the stadium, which finally allowed the bankrupt museum to pay its overdue real estate taxes to Fredericksburg.

Despite the economic development possibilities, the City of Fredericksburg was unwilling to finance a $30 million ballpark and lease it to the team as originally proposed. Under that proposal, the public would own the facility, but would also absorb the speculative risk. Fredericksburg officials douted that revenue from ballpark rentals, plus tax revenue generated from spinoff development at Celebrate Virginia South and a new Community Development Authority tax district around the ballpark, would be sufficient through the year 2045 to pay the debt.5

after plans for the proposed National Slavery Museum collapsed, the site was proposed for a 5,000-seat minor league baseball stadium

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The opportunity to play organized sports is readily available across Virginia. Various schools (including colleges/universities) have strong fan bases, but the chance to watch a professional sports event in Virginia is limited. The most common professional sports event in Virginia is a minor league baseball game.

One way to determine the state's population centers is to note where minor league baseball teams attract enough paying customers to be economically viable. Stadiums for professional baseball have been built in the cities of Bristol, Danville, Lynchburg, Norfolk, Salem, Richmond, and the counties of Prince William and Pulaski. Loudoun County, and the cities of Fredericksburg and Virginia Beach, were the most recent communities to approve minor league baseball stadiums.

Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads are the only two regions of Virginia with sufficient population to support multiple minor league baseball teams. Both Hampton Roads teams are south of the James River, so the market in Hampton-Williamsburg is underserved.

Supporters of building new sports stadiums present them as economic development projects, justifying public funding to provide a facility for a for-profit private business. Public funds have been used to build coliseums in Hampton, Roanoke, and Richmond, which are multiple use facilities that host concerts, college basketball tournaments, even tractor pulls.

The 2008-13 economic recession blocked Prince William's plans for subsidize a new ballpark for its AA baseball team, the Potomac Nationals. Art Silber, the owner of the team, then arranged for the Virginia Department of Transportation to build a commuter parking garage next to I-95 adjacent to the site of a new 6,000-7,000 seat stadium that would be built with $25 million of private funding.

the AA Potomac Nationals have played in Pfitzner Stadium, in Prince William County, since 1984

The plan was for a parking garage funded by the public to be used for commuters at Potomac Town Center during the day, and to be used by ballpark customers attending evening and weekend ballgames. The state would be getting more use of its investment in the garage, and the owner of the baseball team would not have to purchase expensive land and provide parking at the stadium.

The deal was structured so the state would be subsidizing the private for-profit ball club with free parking. At the end of the 2016 season, the garage was still not built and the Potomac Nationals were still playing on the Pfitzner Stadium behind the McCoart Administrative Center, as they had since 1984.6

the new 6-000-7,000 seat ballpark planned for the Potomac Nationals was expected to require $25 million in private funding, separate from a parking garage funded by the state

Source: Washington Business Journal, New Potomac Nationals ballpark is a dream deferred. Is it at risk?

Loudoun County officials approved a new stadium for professional soccer and minor league baseball teams in 2009. The stadium was part of the controversial rezoning for the $2 billion Kincora Village Center at the intersection of routes 7 and 28, which changed the land use authorization on 314 acres from commercial office development to residential and mixed-use.

County officials highlighted the strategic value of sports entertainment attracting young professionals to Loudoun (vs. Bethesda or Alexandria), and the developer argued during the process:7

The ballpark was supposed to open in 2011, but construction was integrated with the development of Kincora Village and the 2009-2012 recession slowed that project. In 2012 the investors in the proposed Loudoun Hounds baseball team moved the planned stadium to a different development a mile away at the interchange of Route 7 and Loudoun County Parkway.

The ball park at the new site, One Loudoun, was planned with 5,500 fixed seats and with a total capacity of 10,000 people for some events. The plan was to complete the stadium by 2014, but by the end of 2016 no ballpark had been constructed.8

The only AAA baseball team in the state, the Richmond Braves, left in 2009 after the city was unable to build a new stadium as promised. The Atlanta Braves moved their AAA team to a suburb of Atlanta which offered a new facility with skyboxes. The iconic sculpture of a Native American was removed from the ballpark, and installed on top of an old cigarette factory that had been converted into a housing complex on Church Hill.

the sculpture designed for the home stadium of the Richmond Braves (titled "Connecticut") moved to Church Hill after the team moved to Georgia

Richmond recruited a AA team as a replacement, and promised to build a new stadium for the "Squirrels." After the city was unable to get support from Henrico County and Chesterfield County to fund a new regional facility at the current site on the Boulevard, Richmond's mayor endorsed building a baseball stadium in Shockoe Valley.

An entertainment facility drawing crowds would help revitalize the Shockoe Valley area, especially the restaurant businesses. However, the city - not the counties - would benefit from increased meal tax revenues. If the surrounding counties were not going to benefit from the new stadium, there is little reason for county officials to invest tax dollars for transportation improvements near the site.

the East Coast Surfing Championships bring a crowd to Virginia Beach

Source: Virginia Tourism Corporation, East Coast Surfing Championships

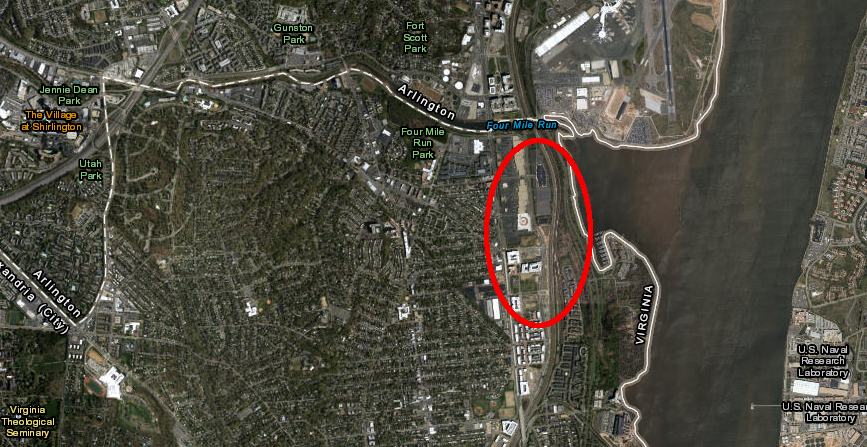

A proposal to build a new football stadium at Potomac Yard in Alexandria, to replace RFK Stadium in DC, failed to attract the Washington Redskins to play on Sundays in Virginia.

Governor Wilder supported the plan, but local officials objected to the traffic impacts. Alexandria and Arlington were concerned that congestion would not be mitigated adequately by the proposal to add a new Potomac Yard Metro station near the stadium. FedEx Field was ultimately built at Largo in the Maryland suburbs at a location without a nearby Metrorail station, and traffic jams on the I-495 Beltway near Largo became routine on game days.

The Washington Redskins did move their football training camp from Loudoun County to Richmond in 2013, after getting a contract with financial guarantees for pre-game revenues.

when the Washington Redskins were planning to move from RFK Stadium in Washington DC, Governor Wilder tried to get them to build a new football stadium at Potomac Yards

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Events involving the best professionals in a sport do occur in Virginia. NASCAR has used racetracks at Martinsville and Richmond since that sport started, professional golf tournaments have been played at the Robert Trent Jones golf course in Gainesville, and the East Coast Surfing Championships have been at Virginia Beach for 50 years.

The only major league ball team to play in Virginia was the Virginia Squires basketball team.

The Squires played in the early 1970's in the upstart American Basketball Association (ABA) before its merger into the National Basketball Association (NBA). In 1973 the team included two future All-Stars, George "The Iceman" Gervin and Julius "Dr. J" Erving. The 1974 ABA All-Star Game was played at the Scope coliseum in Norfolk. However, the Virginia Squires ABA franchise folded in 1976, just before the ABA-NBA merger.

The team's owner was unable to generate sufficient revenue despite playing games in two of Virginia's most populated areas, Richmond and Hampton Roads. The Virginia Squires played one year in Roanoke before abandoning that market, but the inability to generate revenue from the large population in Northern Virginia was fatal to the economics of the ABA team. Before the ABA moved the Oakland, California franchise to Virginia in 1969, the NBA had already located the Bullets (later renamed the Wizards) in Washington DC. As a result, the market for the Virginia Squires was restricted to the southern half of Virginia.

Survival of the ABA teams until the merger with the NBA in 1976 depended upon television revenue. The owner of the Virginia Squires noted:9

the Virginia Squires played at the coliseum in Hampton (as well as the Old Dominion University fieldhouse and the Arena in Richmond)

Source: Structurae, Hampton Coliseum

Hampton Roads does not have the population required to support a major league team. The Triple-A affiliate of the Baltimore Orioles in the International League, the Norfolk Tides, play in a new ballpark at Harbor Park, but the area lacks the critical mass of people. Virginia Beach and Norfolk are in a cul-de-sac isolated from other population centers by the James River on the north, and there are no people to the east due to the Atlantic Ocean.

Several times, professional sports teams have threatened to move to Norfolk or Virginia Beach. Norfolk came close to getting a National Hockey League (NHL) expansion team in 1997 and attracting the National Basketball Association (NBA) Charlotte Hornets in 2001.

In the end, proposals to place a major league basketball team in the region have always ended up being a negotiating ploy for the teams to get a better deal elsewhere. Instead of authorizing a new Hampton Roads Rhinos hockey team, the NHL moved the Hartford team to Raleigh, North Carolina. The Charlotte Hornets moved to New Orleans.

Fans of a major league team noted that the absence of competition would be an advantage. Large urban areas have multiple major league teams, but the fan base in Hampton Roads would focus on only one. The cuktural impact of being the obly major league franchise in Hampton Roads could benefit both the region and the team:10

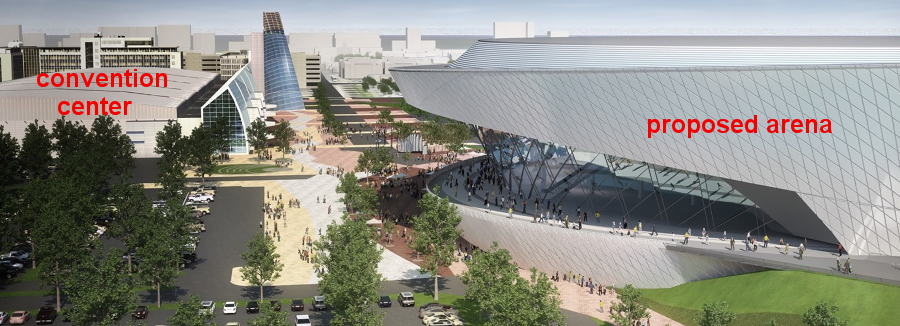

In 2013, the Sacramento Kings hinted that they were willing to move to Virginia Beach. The deal was based on the assumption that the city would construct a new $350 million arena near the Virginia Beach Convention Center, large enough for 18,000 people. The state of Virginia would fund a $150 million relocation package for the privately-owned team, and Virginia Beach would provide $241 million for arena construction. When the arena was not needed for basketball, LiveNation and Comcast would schedule entertainment events.11

efforts to bring NBA basketball to Hampton Roads have always failed, including the attempt to attract the Sacramento Kings in 2013

The proposed cost of the new NBA arena in Virginia Beach was relatively high. At the time, the average cost of NBA stadiums was $285 million and the average public subsidy for building them was $102 million.

Proposals for public funding cite the public benefits of a community hosting a major league team. Intangible benefits include building a sense of regional community across economic/racial lines, and attracting the "creative class" of young professionals who are likely to start a new business and expanding economic growth in an area.

Near the specific site of a new arena/stadium, claimed benefits include urban development and neighborhood revitalization, as demonstrated by the $720 million Washington Nationals baseball stadium in Washington DC. The public funded $635 million of that cost, and the subsequent transformation of the neighborhood has been dramatic.

Public officials in other areas have rejected requests to subsidize new stadiums, doubting that increased tax revenue over time would equal the initial investment of public funding. In 2013, Atlanta let its major league baseball team (the "Atlanta" Braves) move to Cobb County. City officials declined to provide a $200 million subsidy to replace Turner Stadium built less than 20 years earlier, based on a judgment that Atlanta had higher priorities for infrastructure improvements.12

In 2014, Virginia Beach committed to provide city-owned land and $7.5 million in road improvements in order to facilitate a private group's plan to build a 5,000-seat baseball stadium and 17 new ball fields in the city. The estimated total cost was $40-$50 million.13

In 2014, a private developer also got city funding for a proposed 18,000 seat arena next to the Virginia Beach Convention Center, leasing nearly six acres of city-owned land. Virginia Beach agreed to a 1% increase in the city's hotel tax, using that revenue to reimburse the developer up to $476 million over 33 years. The developer agreed to invest $40 million in equity and to obtain a $170 million loan to finance construction costs.

the proposed 18,000 seat arena in Virginia Beach would be next to the Convention Center

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

That deal collapsed when the developer could not obtain the loan as planned. A revised proposal involved borrowing from the bond market, then cut the developers equity investment by half and dropped the requirement that the bond be rated as investment grade. The rating would define the interest rates, enabling the city to be confident about its plan to use tax revenues to ultimately pay off those bonds.

The revision required approval from at least 9 of the 11 members on City Council, because the city-owned land would be leased for 60 years. Only 8 supported the proposal in October, 2016. Once again, plans were not converted into reality.14

Today, the Hampton Roads region remains the largest metropolitan area in the United States without a professional major league team. A year after the Sacramento Kings NBA basketball team chose to remain in California, a Sacramento TV station suggested the absence of a team-ready professional sports arena, rather than the low total population, was the key problem:15

Not everyone agreed with the mayor's dream of attracting a major league sports franchise. After the threat of the Sacramento Kings to move resulted in a decision by Sacramento to subsidize half the cost of a new arena, a Hampton Roads columist wrote in 2013:

in 2016,the Virginia Beach City Council rejected a proposed refinancing that would have led to construction of a speculative arena to attract a major league hockey or basketball team

Source: The ESG Companies, World-Class Entertainment in Virginia - Coming Soon!

Virginia Beach hosts the East Coast Surfing Championships in August

Source: East Coast Surfing Championships

the Prince William Golf Course struggled to generate enough revenue to pay for both capital and operations costs

Source: Historic Prince William, Prince William Golf Course - #257