Stone House at Manassas Battlefield

Source: Library of Congress, Battlefield of Bull Run. Stone house on Warrenton Pike (March, 1862)

Stone House at Manassas Battlefield

Source: Library of Congress, Battlefield of Bull Run. Stone house on Warrenton Pike (March, 1862)

Stone House at Manassas Battlefield, at intersection of Route 29 and Route 234

Source: Historic Prince William, Aerial Photo Survey 2019

Stone House at Manassas Battlefield

Source: Library of Congress, Battlefield of Bull Run, Lewis' house

Judith Henry's house was destroyed in the First Manassas battle (July, 1861)

Source: Library of Congress, Battlefield of Bull Run, ruins of Henry house

the Stone Bridge over Bull Run was destroyed when Confederate forces evacuated Northern Virginia in March, 1862

Source: Library of Congress, Battlefield of Bull Run, ruins of the stone bridge and second image

in 1961, horse-drawn artillery slowed cars coming to the centennial event at the park

hayfields at Manassas Battlefield, north of Route 29 and east of Featherbed Road

Source: Historic Prince William, Aerial Photo Survey 2019

hayfields at Manassas Battlefield, near Dogan House

Source: Historic Prince William, Aerial Photo Survey 2019

reconstructed, two-story Henry House at Manassas Battlefield

Source: Historic Prince William, Aerial Photo Survey 2019

National Park Service visitor center on Henry Hill at Manassas National Battlefield Park

Source: Historic Prince William, Aerial Photo Survey 2019

looking north past National Park Service visitor center on Henry Hill towards Stone House

Source: Historic Prince William, Aerial Photo Survey 2019

prescribed fire at Manassas Battlefield on March 29, 2019

Source: Historic Prince William, Aerial Photo Survey 2019

prescribed fire at Manassas Battlefield on March 29, 2019

Source: Historic Prince William, Aerial Photo Survey 2019

prescribed fire at Manassas Battlefield on March 29, 2019

Source: Historic Prince William, Aerial Photo Survey 2019

full moon rising at Manassas Battlefield, looking towards future site of I-66 ramps

Triassic sandstone wall around Ball family cemetery

Ball family cemetery

To keep the historic landscape pattern with open fields, the National Park Service leases hayfields to local farmers. All the fields have been converted to warm season grasses. No cattle graze in the pastures, so there is no need to have trample-resistant (but not native) Fescue 31.

East of Route 234 near Portici, the hay lessee uses low-end equipment in order to minimize expenses. The square hay bales he produced in 2019 sold for $3.00 each if the hay was soft enough for horses, and if the local customer with a horse farm came in the evening to collect the bales.

If the grass was older when cut, or if it rained on the bales, then the cellulose would be more dominant. There was no barn for hay storage, so one challenge was to sell fast. Cows would eat rough hay, and the really rough bales could be sold at $2.50 each to hydromulch companies. They used it for reseeding development sites and parts of road construction projects that needed to be revegetated for erosion and sediment control.

He could harvest up to 1,000 bales a day using basic equipment and with two men working, one driving the tractor and one shifting bales on the hay wagon. If a mother rabbit jumped in front of the tractor, then he would swerve to avoid a nest and leave some hay uncut. If his equipment hit a rock when raking the hay, repairs could cost $1,000. Harvesting hay at the battlefield for that operator was not a highly-profitable business.

West of Route 234, a different hay operator used more-expensive equipment. Tractors had cabs for comfort, and the cut hay was packed into huge round bales. Mushroom farmers in Pennsylvania purchased that hay.1

warm season grasses in hayfield near Portici, before first cutting in May 2019

hay lease operator near Portici uses simple equipment to make square bales

the hay lease operator near Portici loaded square bales on a wagon

with over 40' of rain annually, active management is required to keep the fields at Manassas Battlefield from re-growing naturally into forests

looking south towards the ridge where Portici once stood

The name of Brawner Farm is based on the tenant farmer family who lived there in 1862 in a one-story house, with perhaps half the footprint of the current structure. The farm was owned by the Douglas family, but George Douglas died in 1855. His widow rented the house and farm in 1857 to John C. and Jane Brawner. They had five children, and worked the farm without owning enslaved people.

There is no archeological or written evidence of the house being destroyed in the 1862 battle or at a later date, but today there is a two-story house at the site. The first floor of the northern part is a structure built around 1800 and moved to the site after the battle; there are no bullets or shell fragments in the wood of the house, but plenty within the yard around it. The southern wing was constructed around 1904, when William Davis owned it.2

the farmhouse occupied by the Brawners in 1862 was a one-story structure, with perhaps half the footprint of the current structure

diabase and sandstone blocks, remnants of chimney/foundation of slave quarters at farm occupied by Brawner family in 1862

warm season grasses grow quickly, once temperatures at night stay above 60°F

effective use of cannon near the Brawner farmhouse were key to the Confederate victory at Second Manassas

the National Park Service cut down a century-old forest to restore sightlines for visitors to understand how cannon shaped the Confederate victory at Second Manassas

near the Brawner farmhouse, the park manages some grasslands through burning (left) and through mowing (right)

the fully-accessible trail to the Brawner farmhouse includes a bridge over an intermittent stream

artificially-maintained meadows at the park provide natural beauty and food for pollinating insects

Confederates moving from Manassas to the Peninsula destroyed the Stone Bridge in March, 1862

Source: Alexander Gardner, Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War

Indian Grass (Sorghastrum nutans) in August, 2019, after prescribed burn the previous March

Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) in August, 2019, after prescribed burn the previous March

buring two soldiers at Arlington National Cemetery, after discovery during 2018 archeological dig of Civil War surgeon's burial pit

Source: National Park Service, Interment at Arlington National Cemetery

restoring the Manassas Battlefield to historical accuracy required removing two gas stations

Source: National Park Service, NPS History Collection - Manassas National Battlefield Park

modern gas stations were not consistent with efforts to restore the park's landscape to its 1861-62 appearance

Source: National Archives, Gasoline Station, Bull Run, Virginia, on U.S. 211

30 years after the 1988 Federal acquisition of the Second Manassas battlefield, the parcels platted for a housing subdivision were still evident in county records

Source: Prince William County, County Mapper

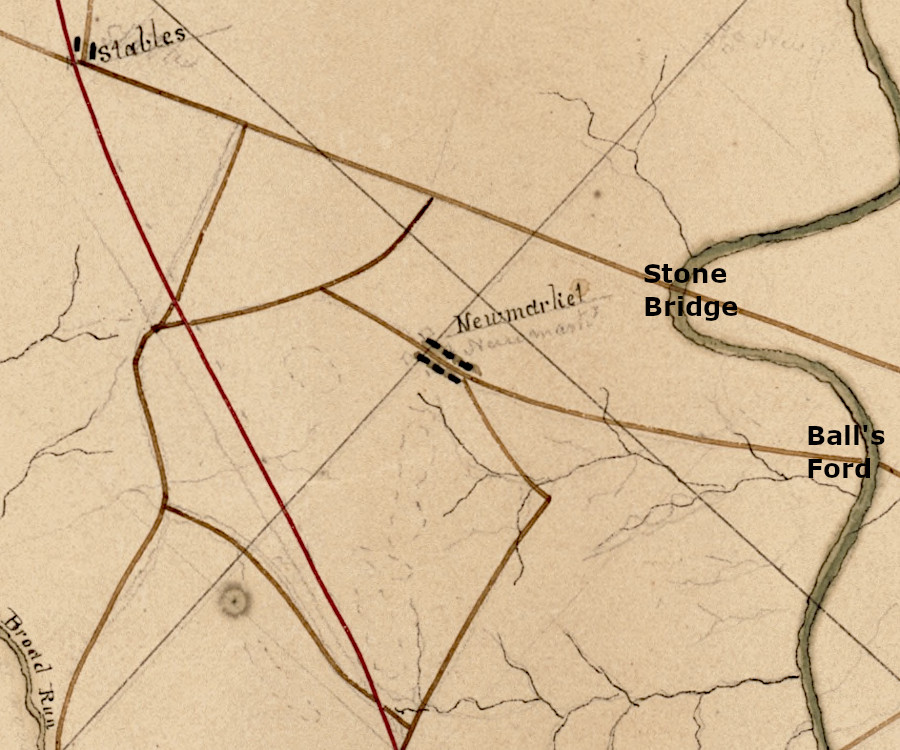

site of the future Manassas Battlefield, just before the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Alexandria, Fairfax, Prince William, Stafford, and portions of the adjacent county's (by Washington Blythe, 1860?)

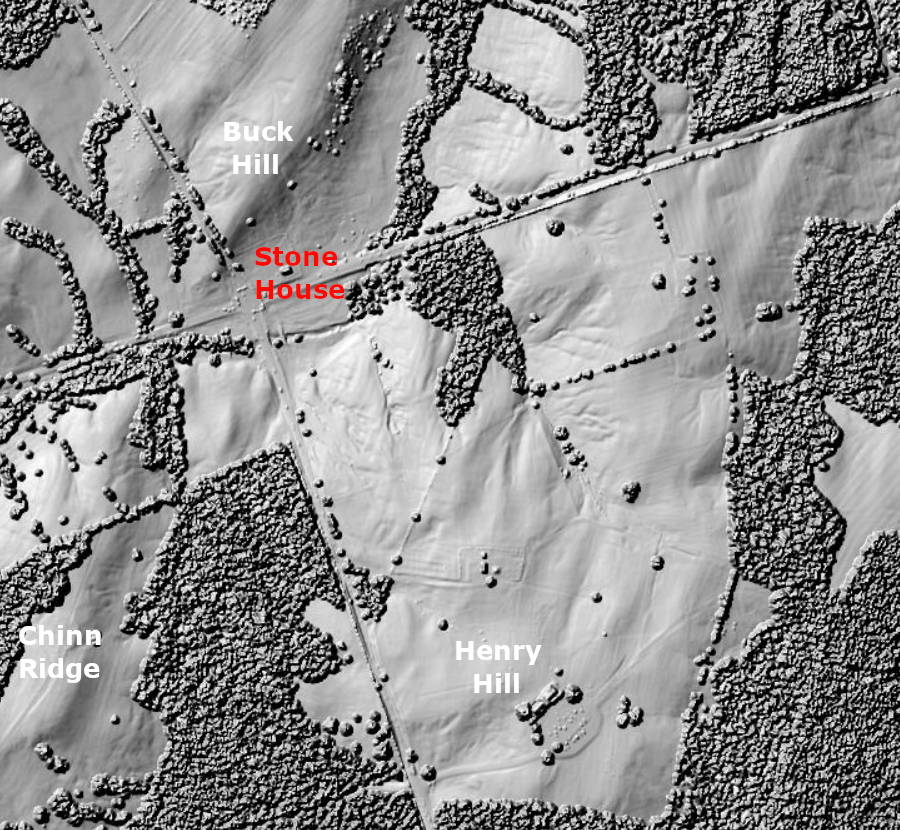

LIDAR reveals the topography of the First Manassas battlefield

Source: Fairfax County, LiDAR Digital Surface Model -2018

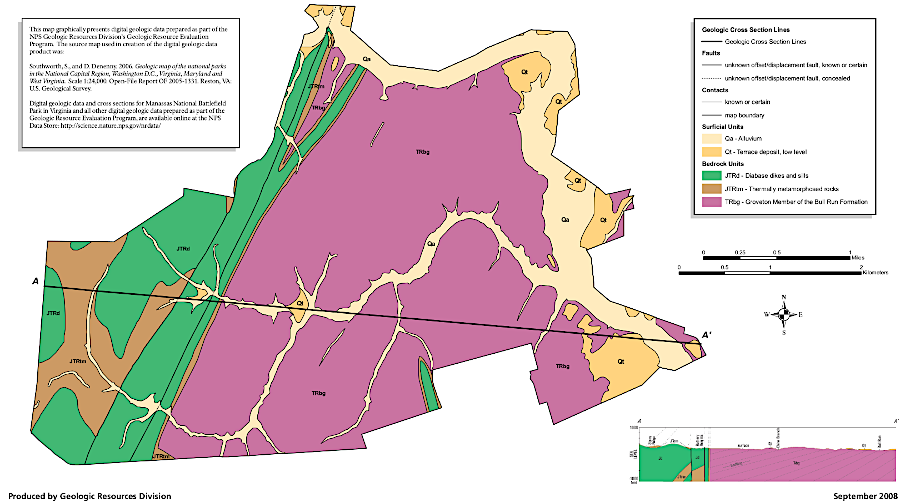

the bedrock at Manassas Battlefield National Park consists of Triassic Period sandstone and younger Jurassic Period volcanic intrusions

Source: National Park Service, Geologic Map of Manassas National Battlefield Park

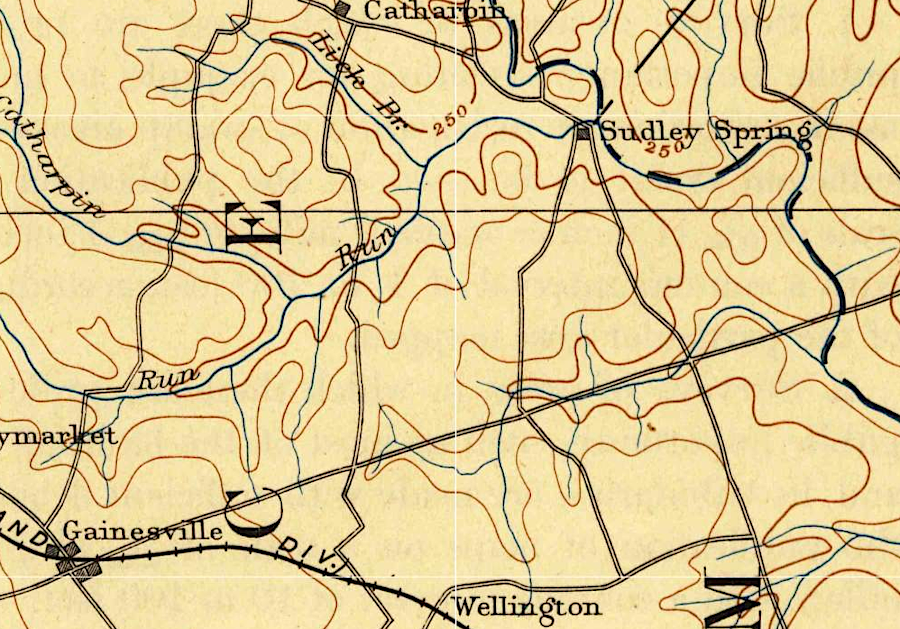

after the fighting in 1861-62, the battlefield land returned to farm use

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Thorofare Gap 1:250,000 topographic quadrangle (1894)