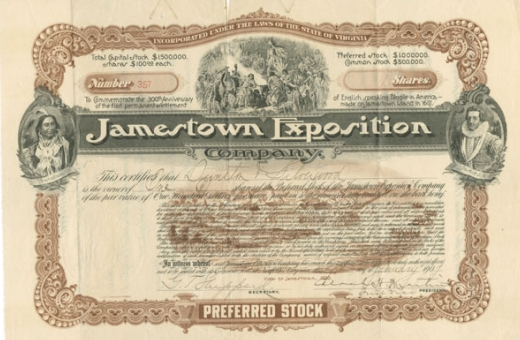

sale of stock to private investors helped to financed the Jamestown Exposition, along with government grants

Source: Library of Virginia, This Day In Virginia History: January 9, 1907

sale of stock to private investors helped to financed the Jamestown Exposition, along with government grants

Source: Library of Virginia, This Day In Virginia History: January 9, 1907

The commemoration of Jamestown's 300th anniversary was initiated by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, and organized and managed by the private sector.

No government agency determined the location of the 1907 Jamestown Exposition. The Federal government and the state of Virginia endorsed the effort and provided funding and exhibits, but the exposition occurred before the National Park Service was founded in 1916 or the Virginia State Parks system was founded 20 years later.

Business leaders in Hampton Roads organized the event. Private investors chose the location, and decided not to base the 1907 Jamestown Exposition at Jamestown. The seven-month exposition was presented at isolated, undeveloped Sewells Point, where expensive infrastructure had to be constructed.

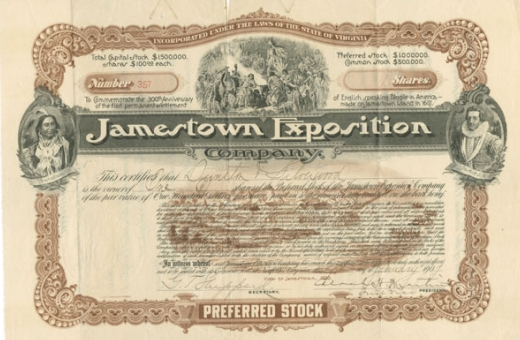

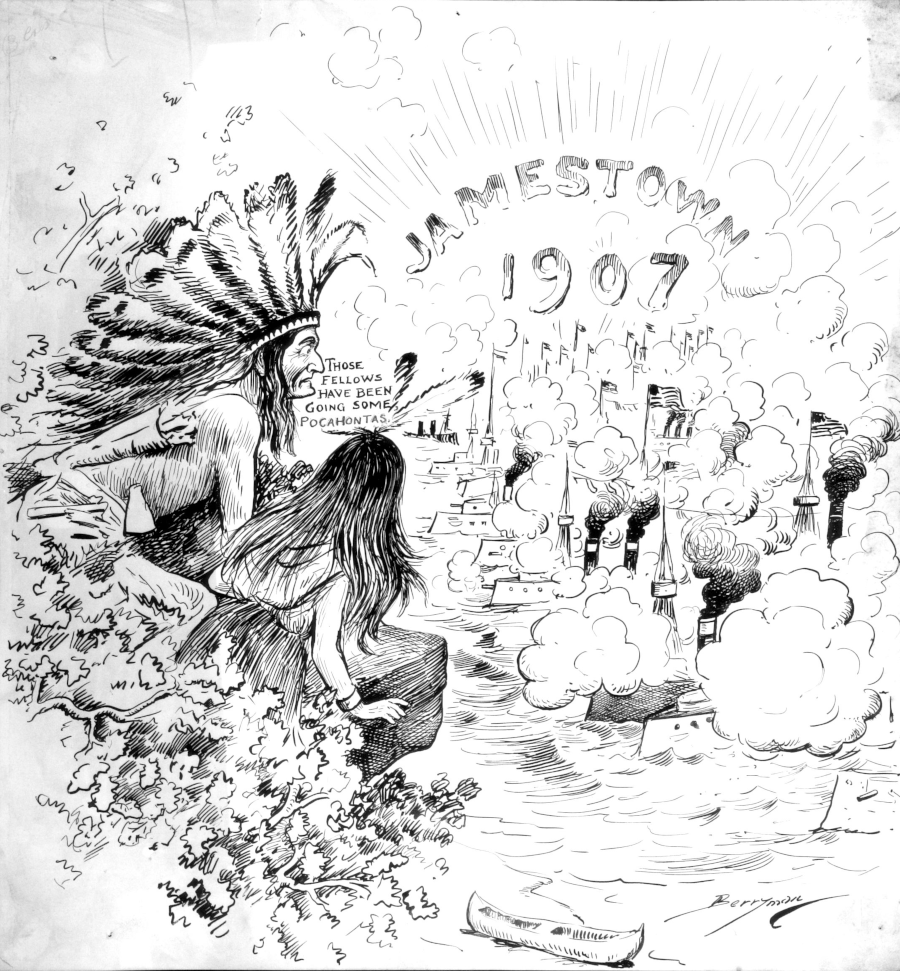

1907 cartoon in the Washington Evening Star suggesting Powhatan's reaction to cannon fire from U.S. Navy warships commemorating the 1607 arrival of English colonists

Source: National Archives, Jamestown 1907

A one-day event comparable to the 1857 and 1807 ceremonies could have been held on the historic grounds where English colonists had arrived in 1607, but there were no water/sewage facilities and no shelter for large numbers of visitors on the island.

The businessmen responsible for organizing the event determined that the 300th anniversary should be a months-long national exposition rather than a simple ceremony. Something offered over seven months would attract millions of tourists and stimulate the regional economy. With common expectations, the business community in southeastern Virginia competed with Richmond to obtain the exclusive right to host the anniversary.

Quick action by the Hampton Roads communities blocked the possibility of holding major events in Richmond. Tidewater business leaders ensured most tourists would end up at Sewells Point, not upstream at the Fall Line.

The process started in 1900 when the Business Men's Association of Williamsburg (predecessor to the modern Chamber of Commerce) proposed an official celebration of the 300th anniversary. The male-dominated business community took responsibility for the event, though the "patriot ladies" of the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities remained involved and played a key role in obtaining Federal and state subsidies.

In 1901 business leaders in Newport News proposed creating a national exposition, the equivalent of a world's fair on the scale of the Philadelphia Centennial of 1876 and the Pan-American Exposition then underway at Buffalo. Norfolk and Portsmouth business leaders feared commemorative activities would be concentrated on the Peninsula rather than on the south side of the James River, but were able to get all Hampton Roads communities to unite in one effort to ensured the commemoration would not be based in the state capital at Richmond.

The separate cities of Norfolk, Portsmouth, Newport News, the town of Berkley, plus the counties of Norfolk, Princess Anne, Nansemond, Isle of Wight, Elizabeth City, and Warwick ultimately reconciled their competing interests:1

Richmond reacted to the Hampton Roads initiative and proposed splitting the exposition. A large naval event would be held in Hampton Roads, but the land-based activities would be centered in Richmond. The proposal to divide the events between two locations was rejected by the General Assembly, which chartered the Jamestown Exposition Company in 1901 and gave it exclusive authority to hold the commemorative "exposition or fair at some place adjacent to the waters of Hampton Roads" and to manage activities at Jamestown in partnership with the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities. Notably, Williamsburg and Richmond were not included in the management of the exposition.2

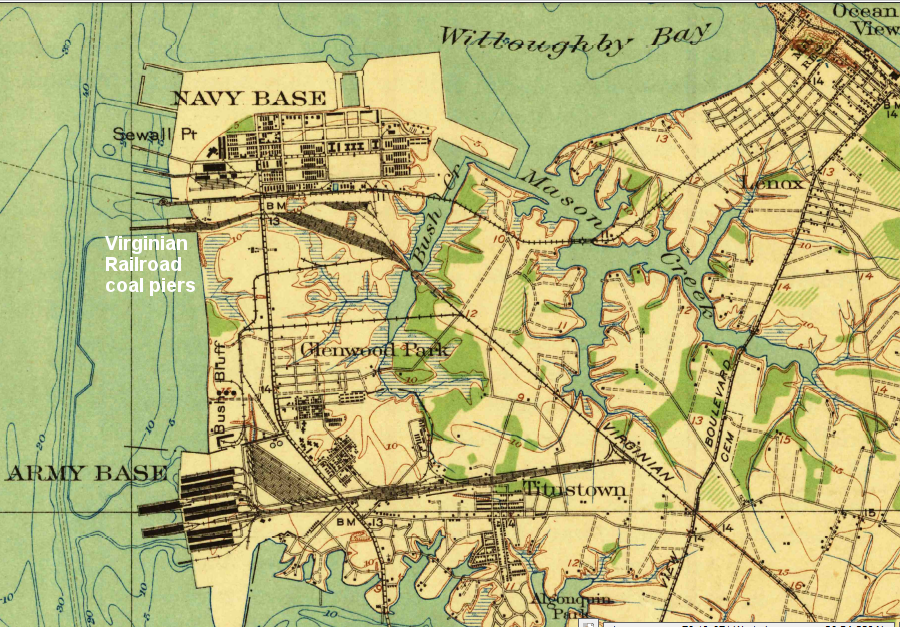

In 1902 the site committee chose 340 acres of undeveloped land on Sewells Point. It was in Norfolk County, "adjacent to the waters of Hampton Roads" but also equally far from the sponsoring cities. The company purchased rather than leased the land, and planned for permanent structures so the event would not just fade into memory after 1907.3

in 1907 Sewells Point was far enough away from Hampton, Newport News, Portsmouth, and Norfolk to be "neutral" territory, providing roughly equal economic benefits to each city

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Norfolk Special 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (1907)

In 1903 the Virginia General Assembly appropriated $200,000 for the exposition, but the new state constitution prohibited the cities/counties from issuing bonds to subsidize the private Jamestown Exposition Company. The company was slow to sell stock, and just barely met the deadline required by the state to raise private money before release of the state funds. The first attempt in 1904 to get the US Congress to designate the event as a national one, and to provide an appropriation to subsidize costs, failed. In 1905 Congress authorized President Roosevelt to issue a proclamation declaring national support for the exposition (which he did immediately) and to invite navies of other nations to Hampton Roads in 1907.4

In 1906 the Virginia General Assembly appropriated an additional $100,000 for an exhibit building and military display at the exposition, and other states made similar commitments with the expectation that the US Congress would provide funding for the event.5

electric lights illuminated buildings at the Jamestown Exposition in 1907

Source: Jamestown, Virginia: The Townsite and Its Story (p.35)

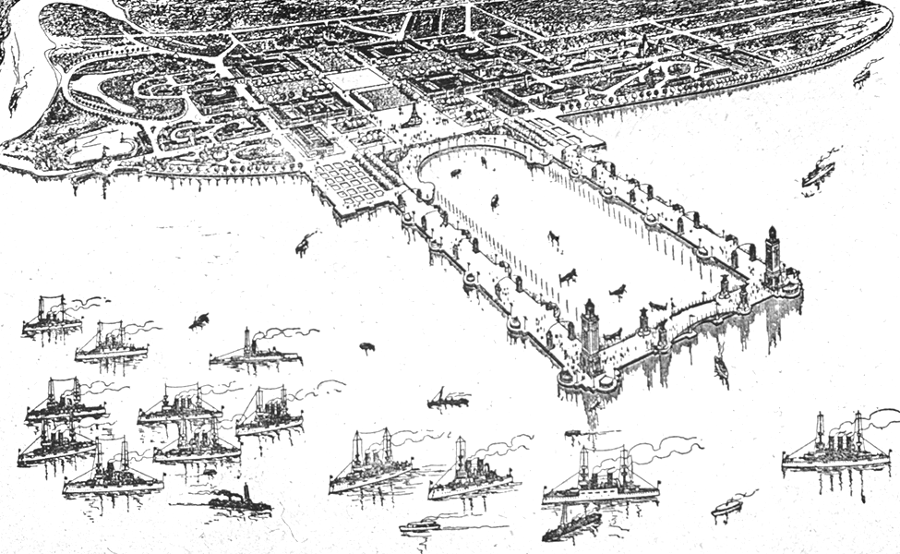

Congress loaned $1 million to the exposition, but Speaker Cannon delayed any financial commitment from the Federal government until February, 1907. Funding shortages affected the initial development of the site, and many buildings were not completed with exhibits installed until more than a month after the April 26 opening day. The grand waterfront piers designed to welcome passengers arriving by steamboat were not completed until September, 1907, and the exhibition was complete only for its last six weeks until closing on November 30, 1907.6

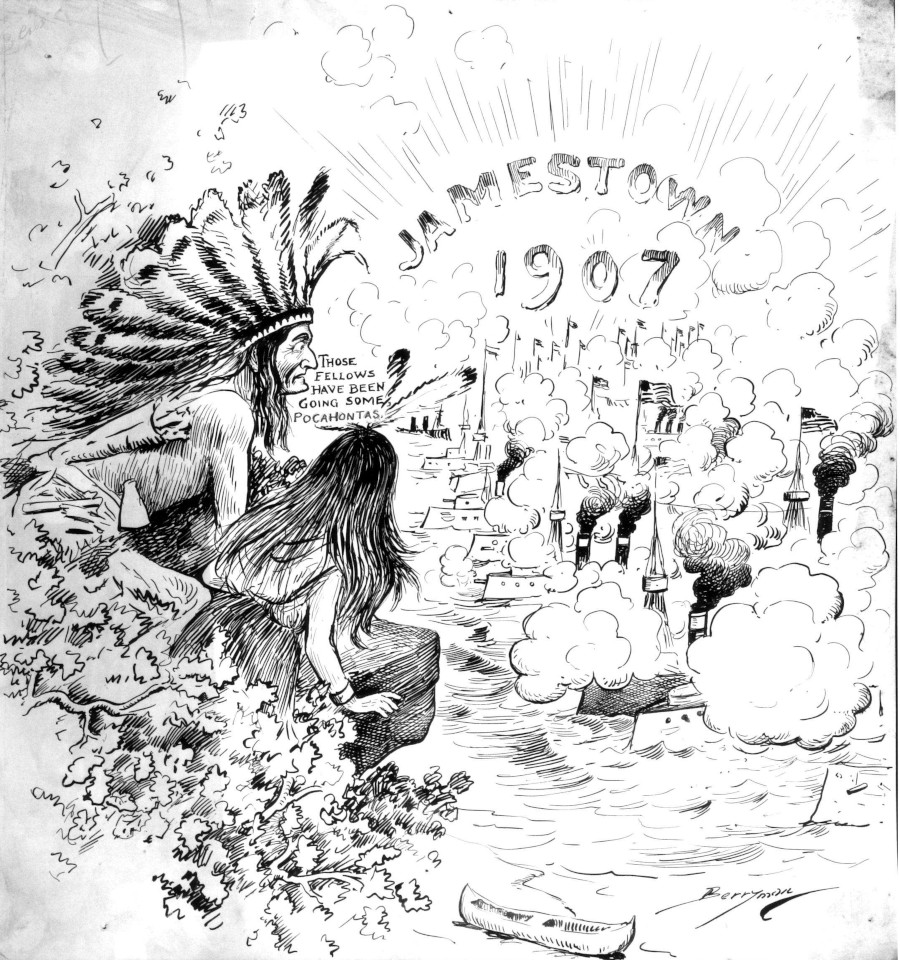

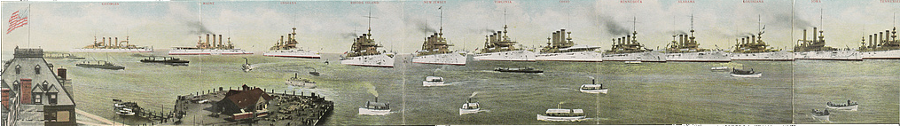

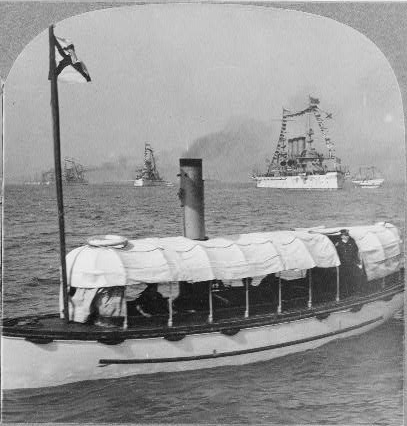

President Theodore Roosevelt endorsed the exposition, attended on opening day, and had the Great White Fleet anchor in Hampton Roads before later sailing around the world to demonstrate America's new military power after the Spanish-American War.7

in 1907, the US Navy displayed its power at Hampton Roads during the celebration of the 300th anniversary of English settlement at Jamestown

Source: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command, Jamestown Exposition Naval Review, June 1907 (Photo #NH 105806)

the Great White Fleet sailed around the world after the Jamestown Exposition, making clear the US was now an international seapower

Source: Library of Congress, U. S. Naval display, Hampton Roads, Jamestown, Virginia

Most of the 1907 events were held on Sewells Point, a part of Norfolk County that was annexed into the City of Norfolk in 1923. The first English colonial settlement in Virginia had been located upstream in James City County, but Jamestown lacked facilities to handle tourists. The Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities protected a portion of the island by 1907, but there were no water/sewage facilities or shelters for large numbers of visitors at the site.

The Norfolk/Portsmouth business community campaigned hard to host the Jamestown Exposition in 1907. The authenticity of Jamestown Island was damaged by the presumed loss of the fort through erosion, and (perhaps most importantly) Hampton Roads businesses would not benefit if visitors were concentrated at the original site. After the General Assembly chartered the Jamestown Exhibition Company to manage the Jamestown Tercentenary exposition, it was clear that the celebration would not be located at the alternative site of Richmond or in James City County.

state-sponsored buildings at the Jamestown Exposition lined the waterfront at Sewells Point

Source: Jamestown, Virginia: the townsite and its story (p.24)

The 340 acres purchased at Sewells Point were agricultural land. The site was desirable because it was undeveloped and accessible by water, and because it offered a "neutral" location for the Hampton Roads jurisdictions sponsoring the event. The only historical significance of Sewells Point was related to the Civil War.

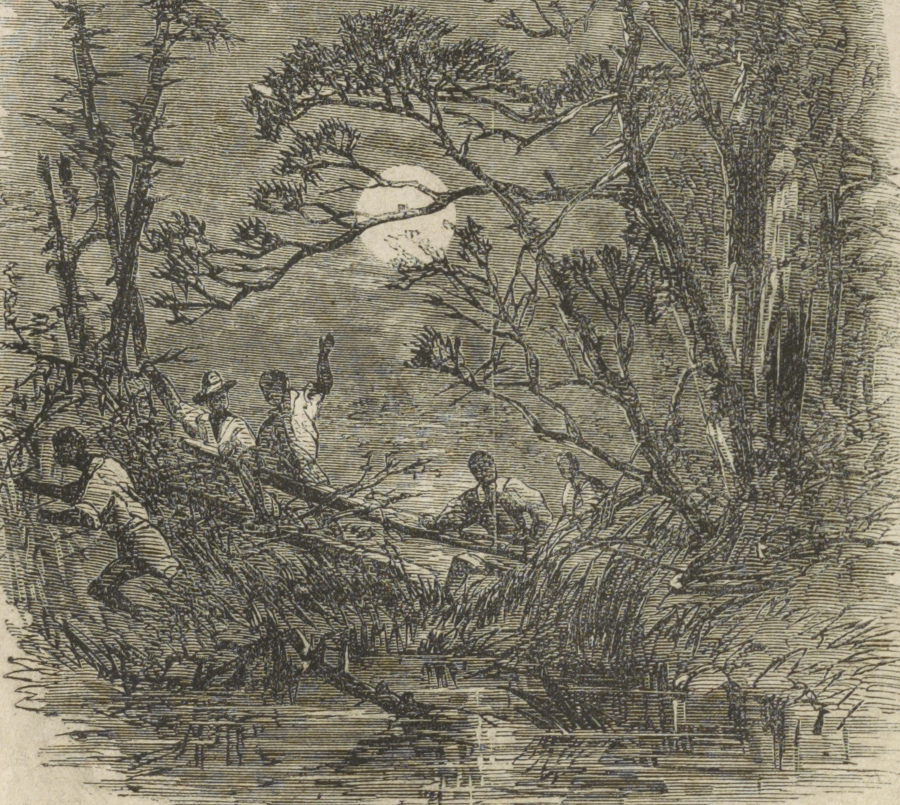

In 1861, Confederate forces had built a fort there, and three enslaved men forced to work on that fort had fled across Hampton Roads. Sheppard Mallory, Frank Baker, and James Townsend made it to Fort Monroe. When their slaveowner's agent demanded their return, Union General Benjamin Butler refused to comply with the Fugitive Slave Act, retained them as "contraband of war," and started the process that ultimately led to the Emancipation Proclamation and the end of slavery.8

In 1907, however, Virginia's political elite had no intent to honor the courage of the first contrabands or to commemorate the heritage of slavery. It would take another century until the Sesquicentennial (150th anniversary) of the Civil War before the story of contrabands at Fort Monroe would be highlighted.

the 1907 Tercentennary of Jamestown ignored the slavery-related significance of the Sewells Point location

Source: Library of Congress, Stampede among the Negroes in Virginia - their arrival at Fortress Monroe (from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, June 8, 1861)

In 1907, Sewells Point had no utilities. A private corporation, the Norfolk County Water Company, provided water within Norfolk County and extended its lines to Sewell's Point, but lacked a drinking water plant capable of meeting the demand of the anticipated number of visitors. The city of Norfolk ended up providing the water, and the exposition built a 2-million gallon reservoir at Sewells Point that was filled at night and emptied by visitors during the day (and also provided a supply of water in case the wooden structures had caught fire).9

The Virginian Railroad constructed a spur line to provide access for passengers arriving on trains. Norfolk County and the city of Norfolk cooperated to build a new road from the Norfolk city limits to Sewells Point. The Jamestown Boulevard (now Hampton Boulevard) was named Maryland Avenue within the boundaries of the exposition, and even today on the Norfolk Navy Base the road still retains that name.

The rail and road entrances were not co-located, and the Board of Design plans for a main entrance with an impressive welcoming vista were not implemented. The long walk from the entrance to the exhibit buildings may have limited revenue by discouraging repeat visits from local residents.

The long delay in completing the piers made access by water inconvenient, but was matched by equally poor access for those who had to walk long distances from the and entrance. The difficulty in getting to the exhibitions caused some to refer to the event as the "Jamestown Imposition."10

cartoonist Clifford Berryman highlighted how the US Navy in 1907 had advanced from the Godspeed, Discovery, and Susan Constant 300 years earlier

Source: National Archives, Jamestown 1907 (by Clifford Berryman, April 26, 1907)

By 1907, 21 states had funded construction of exhibition buildings in two rows, trolley lines were extended from Norfolk, and the Federal government built two piers that allowed visitors to access the site by steamboat. A contemporaneous magazine reported:11

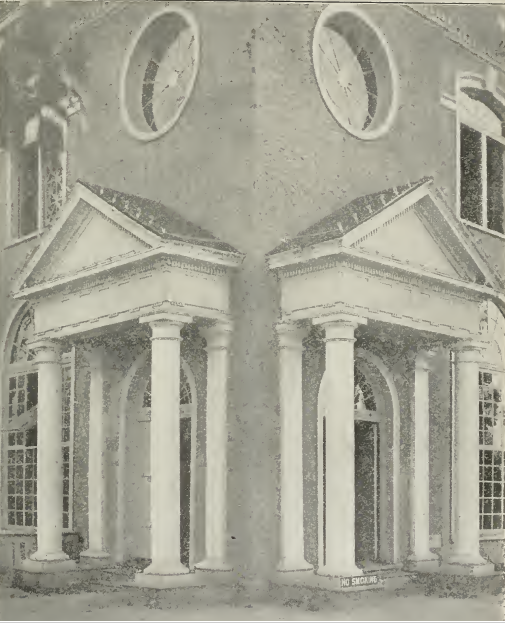

the Virginia Building at the Jamestown Exposition reflected the Georgian architecture of colonial times

Source: Edward H. Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture, Virginia Building (1907 postcard)

this replica of Independence Hall, built for the 1907 Jamestown Exposition, clearly would have been out-of-place if the event had been held on Jamestown Island

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, National Register Nomination: Jamestown Exposition Site Buildings, Norfolk

African-Americans were represented at previous exhibitions, such as the 1876 Centennial Exposition at Philadelphia and the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition South at Atlanta. The exhibits consciously reflected the concepts of white supremacy; blacks were depicted as ignorant slaves on southern plantations or as simplistic banjo players.

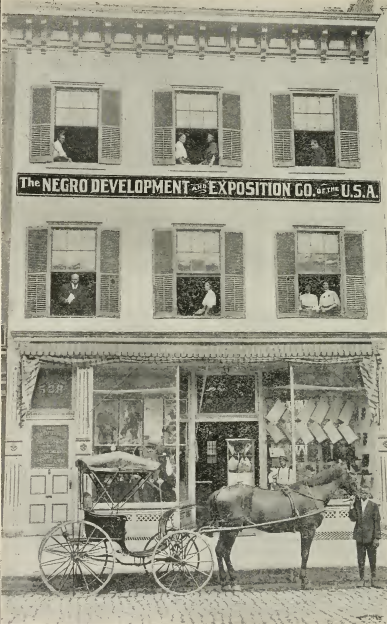

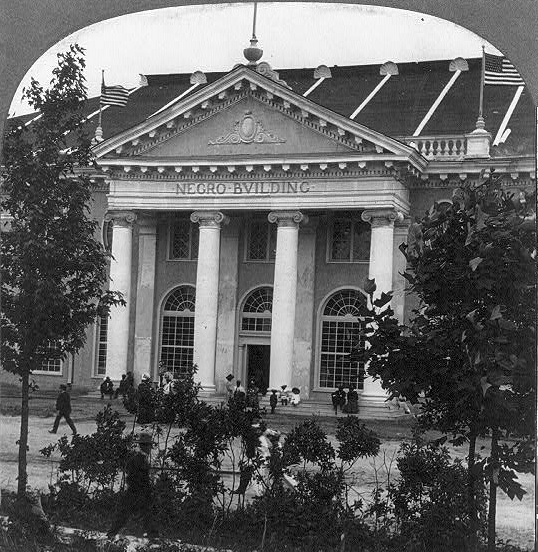

The 1895 Atlanta fair started the tradition of creating "Negro halls" dedicated to African-American culture, and by 1907 segregation was the law in Virginia. The white elite who organized the Jamestown Exposition assigned six acres away from the center of the Jamestown Exposition for a "Negro Building," and the Federal government contributed $100,000. Black leaders got a Virginia state charter for the Negro Development and Exposition Company, and hired black contractors (even black electricians installed the 4,000 electric lights) to construct a building with exhibits to highlight:12

Giles B. Jackson and other black leaders ensured the Jamestown Exposition included a Negro Building with positive stories about social and economic progress in the 40

Source: The Industrial History of the Negro Race of the United States (p.176, p.189)

the Negro Building at the Jamestown Exposition was designed by a black architect (Sidney Pittman), and built by black contractors and workers

Source: The Industrial History of the Negro Race of the United States (p.187)

the Negro Building at the Jamestown Exposition was built by black contractors and workers

Source: The Industrial History of the Negro Race of the United States (p.167)

Black achievements over time were illustrated in 14 dioramas with over 130 painted figures, created by the African-American sculptor Meta Warrick. One of her sculptures depicted the arrival of the first slaves at Point Comfort in 1620, while other showed a fugitive slave escaping white domination. She:13

sculptor Meta Warrick used plaster figures in a diorama to show the first blacks arriving in Virginia in 1619, then depicted through other dioramas how blacks had succeeded and improved their conditions up to 1907

Source: The Industrial History of the Negro Race of the United States (1908)

Creating a segregated building at the event was controversial within the black community, because opponents feared it would reinforce white perceptions of racial superiority. The exhibits were carefully designed not to offend whites while still demonstrating the capacity of blacks to manage businesses, perform industrial operations, write books, publish newspapers, succeed as farmers, and invent new products. The Fisk University singers provided traditional "plantation melodies" twice daily, and one of Meta Warrick's sculptures represented a slave defending his master's home during the Civil War. The Negro Development and Exposition Company was led by the accommodation wing of black leadership associated with Booker T. Washington (who spoke at the exposition), not the confrontational wing led by W.E.B. DuBois.

White exposition leaders did not interfere with the development of the Negro Building exhibits or presentation of the programs, and even designated August 3 as "Negro Day" to encourage more visitors to pay to enter the fair. Gov. Stuart of Virginia never choose to visit the Negro Building, but President Roosevelt stopped by on his second visit on June 10 and publicly shook hands with Giles B. Jackson, who used the title Director-General of the Negro exhibit.14

After the exposition closed, the black leaders who had advocated in favor claimed that the "great Jamestown Negro Exhibit" had succeeded in demonstrating industrial progress and positive characteristics:15

the 1907 exposition included one building dedicated to "Negro" culture

Source: Library of Congress, Exhibits Building testifying to the progress of the African American race -- Jamestown Exposition

Other than the opening day when President Theodore Roosevelt attended, the number of visitors did not match expectations of up to 6 million. Though 2.8 million people visited the site, only half were paid customers.16

The Jamestown Exhibition Company declared bankruptcy less than a month after the exposition closed on November 30, 1907. Some states sold their exhibit buildings to private individuals to serve as private residences (Joseph Deal, who served as the member of the US House of Representatives from the Second District, purchased the Virginia House) while the Fidelity Land and Investment Corporation purchased others. The new owners of the land at Sewells Point spent a decade trying to convince the US Navy to purchase it and build a new naval base, expanding beyond the limits of the Norfolk Navy Yard on the South Branch of the Elizabeth River in Portmouth.17

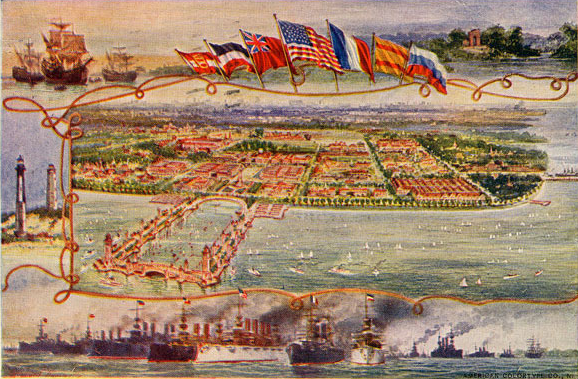

Sewells Point was developed into a temporary town in 1907, then abandoned for a decade

Source: Smithsonian Institution, birds-eye view of the 1907 Jamestown Exposition

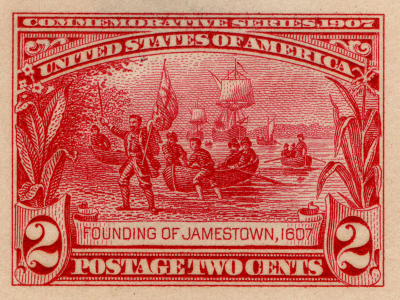

the US Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp in 1907

Source: Smithsonian Institution, The Founding of Jamestown

Jamestown Exposition visitors arrived by boat, and could see the Great White Fleet in Hampton Roads

Source: Library of Congress, Some of the great war ships in Hampton Roads for the Jamestown Exposition--opening day April 26, 1907

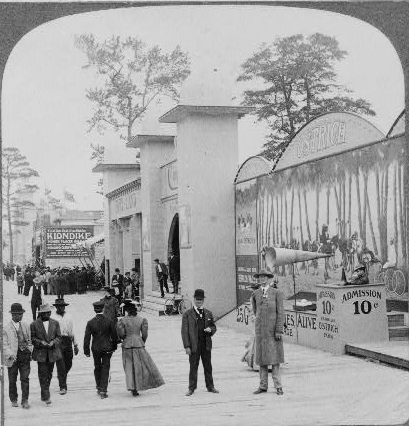

only half of the visitors had to pay admission fees to enter the exposition

Source: Library of Congress, "Shows" from all round the world on "the warpath", Jamestown Exposition, Va.

In 1917, a decade after the exposition closed and after World War I had started, the US Navy finally acquired the land and began constructing the Norfolk Navy Base. The battleships in a modern navy required destroyers, submarines, and other ancillary vessels, and the old facilities on the Elizabeth River in Portsmouth (dating back prior to the Revolutionary War) were too small.18

by 1921 Sewells Point was a Navy base, north of the Virginian Railroad coal piers (which would be incorporated into the base in the 1960's)

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Newport News 15x15 topographic quadrangle (1921)

The Navy has retained 17 remaining buildings from the Jamestown Exposition. Each building has a distinctive architecture (Pennsylvania built a replica of Independence Hall), and those structures were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975.19

the US Navy "repurposed" many buildings from the Jamestown Exposition

Source: Library of Congress, View of Naval Operating Base, Hampton Roads, Va. (1919)

remaining state-sponsored buildings constructed for the 1907 Jamestown Exposition are now south of the golf course at the Norfolk Naval Base

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Norfolk North 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (2013)

Only eight of those buildings are still on their original locations. Others have been modified and/or relocated at various times to accommodate Navy expansion; for example, the North Carolina and Rhode Island houses were combined to create the Senior Bachelor Officers' Quarters. A dozen state exposition buildings are now located on Dillingham Boulevard, named after Captain A. C. Dillingham who was responsible for initial construction of the naval base in 1917. The state exhibit buildings have been converted to serve as executive housing on the naval base and Dillingham Boulevard is known informally as Admirals' Row.20

Source: Library of Congress, Jamestown Exposition, 1907

President Teddy Roosevelt spoke on opening day at the 1907 Jamestown Exposition

Source: Library of Congress, President Roosevelt's arrival at the Jamestown Exposition, Va.

1. Charles E. Hatch, Jr., Jamestown, Virginia: the townsite and its story, National Park Service, 1957, pp.28-30, http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/003800088 (last checked January 1, 2015)

2. Charles E. Hatch, Jr., Jamestown, Virginia: the townsite and its story, National Park Service, 1957, p.33, http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/003800088 (last checked January 1, 2015)

3. Charles E. Hatch, Jr., Jamestown, Virginia: the townsite and its story, National Park Service, 1957, p.101, http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/003800088 (last checked January 1, 2015)

4. Charles E. Hatch, Jr., Jamestown, Virginia: the townsite and its story, National Park Service, 1957, p.39, p.44, p.75 http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/003800088 (last checked January 1, 2015)

5. Charles E. Hatch, Jr., Jamestown, Virginia: the townsite and its story, National Park Service, 1957, p.80 http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/003800088 (last checked January 1, 2015)

6. Charles E. Hatch, Jr., Jamestown, Virginia: the townsite and its story, National Park Service, 1957, p.121, p.130, p.139, p.150, http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/003800088 (last checked January 1, 2015)

7. "The Jamestown Exposition of 1907 and the U.S. Navy Social Studies Lesson Plan," Hampton Roads Naval Museum, p.5, http://www.history.navy.mil/museums/hrnm/files/education_resources/pdfs/expolessonplan.pdf (last checked December 28, 2014)

8. "How Slavery Really Ended in America," The New York Times, April 1, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/03/magazine/mag-03CivilWar-t.html (last checked January 11, 2015)

9. Charles E. Hatch, Jr., Jamestown, Virginia: the townsite and its story, National Park Service, 1957, p.95, http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/003800088 (last checked January 1, 2015)

10. Charles E. Hatch, Jr., Jamestown, Virginia: the townsite and its story, National Park Service, 1957, pp.91-92, pp.96-97, http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/003800088; Harry Kollatz Jr, True Richmond Stories: Historic Tales from Virginia's Capital, The History Press, 2007, p.90, https://books.google.com/books?id=UHMVBAAAQBAJ (last checked January 10, 2015)

11. "Jamestown Exposition Site, Norfolk City, Virginia," National Park Service, http://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/jamestown/; "The Jamestown Exposition," The World's Work, Volume XIV Number 2 (June 1907), p.8935, http://books.google.com/books?id=sojNAAAAMAAJ (last checked December 28, 2014)

12. Giles B. Jackson, D. Webster Davis, The Industrial History of the Negro Race of the United States, The Virginia Press, Richmond (Virginia), 1908, p.138, https://archive.org/details/industrialhistor00jack (last checked December 31, 2014)

13. W. Fitzhugh Brundage, "Meta Warrick's 1907 'Negro Tableaux' and (Re)Presenting African American Historical Memory," The Journal of American History, Volume 89, No. 4 (March 2003), http://www.journalofamericanhistory.org/teaching/2003_03/article.html; Giles B. Jackson, D. Webster Davis, The Industrial History of the Negro Race of the United States, The Virginia Press, Richmond (Virginia), 1908, pp.169-177, p.191, https://archive.org/details/industrialhistor00jack (last checked December 30, 2014)

14. Giles B. Jackson, D. Webster Davis, The Industrial History of the Negro Race of the United States, The Virginia Press, Richmond (Virginia), 1908, p.196, p.200, p.205, p.227, p.264, p.269, https://archive.org/details/industrialhistor00jack (last checked December 30, 2014)

15. Giles B. Jackson, D. Webster Davis, The Industrial History of the Negro Race of the United States, The Virginia Press, Richmond (Virginia), 1908, pp.5-6, https://archive.org/details/industrialhistor00jack (last checked December 30, 2014)

16. Harry Kollatz Jr, True Richmond Stories: Historic Tales from Virginia's Capital, The History Press, 2007, p.90, https://books.google.com/books?id=UHMVBAAAQBAJ (last checked January 10, 2015)

17. "The Jamestown Exposition of 1907 and the U.S. Navy Social Studies Lesson Plan," Hampton Roads Naval Museum, p.8, http://www.history.navy.mil/museums/hrnm/files/education_resources/pdfs/expolessonplan.pdf; Charles E. Hatch, Jr., Jamestown, Virginia: the townsite and its story, National Park Service, 1957, p.151, http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/003800088' "Historic homes still stand on Naval Station Norfolk," The Flagship, May 3, 2007, http://www.norfolknavyflagship.com/news/navy_history/historic-homes-still-stand-on-naval-station-norfolk/article_5625b095-b51e-5ee8-b9c7-2495ac0675d1.html; "Historic homes commemorate beginnings," The Flagship, May 10, 2007, http://www.norfolknavyflagship.com/news/navy_history/historic-homes-commemorate-beginnings/article_8c1cb14b-0bd5-52f6-bde0-2fcb707d34e9.html (last checked January 10, 2015)

18. Bruce Linder, Tidewater's Navy: An Illustrated History, Naval Institute Press, 2005, pp.124-130, https://books.google.com/books?id=awYJ7aSWNWsC; "The Jamestown Exposition of 1907 and the U.S. Navy Social Studies Lesson Plan," Hampton Roads Naval Museum, p.10, http://www.history.navy.mil/museums/hrnm/files/education_resources/pdfs/expolessonplan.pdf (last checked December 28, 2014)

19. Calder Loth, The Virginia Landmarks Register, University of Virginia Press, 1999, p.345, https://books.google.com/books?id=NJa_64aH1iMC (last checked January 10, 2015)

20. "The Jamestown Exposition of 1907 and the U.S. Navy Social Studies Lesson Plan," Hampton Roads Naval Museum, p.8, http://www.history.navy.mil/museums/hrnm/files/education_resources/pdfs/expolessonplan.pdf; "Access to Admirals' Row not a given for flag officers," The Virginian-Pilot, July 30, 2013, http://hamptonroads.com/2013/07/access-admirals-row-not-given-flag-officers; "Historic homes commemorate beginnings," The Flagship, May 10, 2007, http://www.norfolknavyflagship.com/news/navy_history/historic-homes-commemorate-beginnings/article_8c1cb14b-0bd5-52f6-bde0-2fcb707d34e9.html (last checked January 10, 2015)

Sewells Point in Norfolk was chosen to be the site of the 300th anniversary, and was easily accessible by water

Source: Library of Congress, Ter-Centennial Exposition, drawing: bird's eye view, Jamestown, VA (1907)

Source: Library of Congress, International naval review, Hampton Roads, Virginia, 1907