How Can Local Officials Shape Growth in Northern Virginia?

One fundamental way to implement smart growth is to shape the pattern of new development, or redevelopment of existing sites, through zoning.

Local governments have the legal authority to control land use. Local governments can use their inherent police powers to shape development in different areas, without "taking" property as defined in the Fifth Amendment of the US Constitution. Zoning is "free," and requires no compensation to be paid to landowners even when development potential is restricted and land values go down.

The Code of Virginia (Title 15.2 Chapter 22, 15.2-2280) says:

- Any locality may, by ordinance classify the territory under its jurisdiction or any substantial portion thereof into districts of such number, shape and size as it may deem best suited to carry out the purposes of this article, and in each district it may regulate, restrict, permit, prohibit and determine the following:

- 1. The use of land, buildings, structures and other premises for agricultural, business, industrial, residential, flood plain and other specific uses;

- 2. The size, height, area, bulk, location, erection, construction, reconstruction, alteration, repair, maintenance, razing, or removal of structures;

- 3. The areas and dimensions of land, water, and air space to be occupied by buildings, structures and uses, and of courts, yards, and other open spaces to be left unoccupied by uses and structures, including variations in the sizes of lots based on whether a public or community water supply or sewer system is available and used; or

- 4. The excavation or mining of soil or other natural resources.

Stafford County zoning (just south of Prince William County line),

Stafford County zoning (just south of Prince William County line),

encouraging development of office buildings for contractors supporting Quantico Marine Corps Base

(so Stafford residents don't need to commute north any further, and so Stafford gets property taxes)

Source:

Stafford County GIS

In Northern Virginia, disputes over what development is "appropriate" are resolved by the elected officials of towns, cities, and counties. Remember, incorporated towns control land use decisions within their boundaries, but unincorporated areas such as Reston or subdivisions such as Braemar have no such controls, other than authorities of the Home Owner Associations.

If the local government reduces the density permitted on a parcel, then that parcel has been "downzoned." Landowners may object, and might rally political allies to change the decision. Landowners can also argue that the county made a procedural error in the downzoning process, and the decision is not valid. In some cases, the courts will get involved to referee legal fights.

However, state and Federal officials have minimal or no involvement - land use in NOVA is determined at the local level by elected members of Town Councils, City Councils, and Boards of County Supervisors. If you don't like a zoning decision, don't write your Congressman or state delegate in the General Assembly; they really can't help you. Local elected officials rely upon advice from professional staff and appointed planning commissioners, but the big decisions on local land use are made by elected officials (who become very familiar with local geography in the process).

Smart growth encourages defining areas of high density development to absorb the projected population growth in Northern Virginia, rather than allowing development at low density across many acres. Zoning decisions by local officials, at the town/city/county level, determine the maximum density of new housing on private property. Permitted maximum density can vary dramatically on different parcels of land, depending upon the zoning classification.

For example, the "RA14-26" Apartment Dwelling zoning classification in Arlington County alllows 14 dwelling units (meaning townhomes) per acre. The Transitional Residential (TR1UBF) zoning classification in Loudoun County, along Route 50 between Route 28 and Route 15, allows 1 house/acre - if the houses are clustered to protect open space.

The Agricultural Estate (AE) zoning classification in the Rural Area of Prince William County allows no more than 1 house/10 acres. The Residential-Conservation (R-C) District, in the area of Fairfax County next to the Occoquan Reservoir that was "downzoned" in 1982, allows no more than 1 house/5 acres.

Parcels affected by restrictive zoning may have less profit potential, of course. If 10-acre lots are selling for $400,000 each, and a 100-acre farm could be carved into 10 such lots, then the farm is worth $4 million or so. If downzoning reduces the development potential to one house per 20 acres, then only 5 lots could be carved from a 100-acre farm. Perhaps each larger lot might sell for a premium price, but that will not allow the landowner to reap the same profit. If you assume a 50% premium, so each lot sold for $600,000, then a farm with potential to build on only 5 lots would be worth only $3 million while a farm with 10 potential lots would be worth $4 million.

Loudoun County Zoning

AR1 = Agricultural Rural zoning

1 dwelling unit/20 acres (1 du/20 acres)

or 1du/10 acres if clustered together to protect open space

Source: Loudoun County Mapping

|

TR3UBF = Transitional Residential without central utilities,

1 dwelling unit/acre

if clustered so 50% remains open space

Source: Loudoun County Mapping

|

After a multi-year fight, Loudoun County has now downzoned much property west of Route 15 into the AR1 district (20 acre minimum lot sizes) or AR2 district (40 acre minimum lot sizes), in the area that includes Middleburg. The impact on land values was enormous, but the impact on the quality of life was also clear to voters. The intensity of development to be permitted by the county was the key factor in local elections in 1999, 2003, and 2007... and there's still more to come, once this downturn in the housing market is over.

The split regarding development is clearly geographical in Loudoun. Many large-acreage property owners in the western part of the county, especially near Middleburg, do not desire for their land to end up looking like the crowded subdivisions in eastern Loudoun. Those landowners support zoning that limits their ability to subdivide and sell land for a profit. Because zoning could be changed by future politicians, some landowners are permanently limiting the development potential by placing conservation easements on their land.

For more, read:

The economics of development explain why lawyers and developers are so tightly engaged in all the land use planning processes. Landowners get involved to ensure particular pieces of Northern Virginia can be developed to a "highest and best use" that will maximize the economic value of the land. Sometimes, neighbors and even non-government organizations may get involved to prevent what they consider to be inappropriate development of parcels.

One reason the Loudoun rezoning issue was not settled more quickly was that wealthy landowners, working at times through the Piedmont Environmental Council, were able to hire lawyers just as skilled and just as committed as the lawyers working for the pro-development advocates. Normally, the slow-growth advocates are not going to benefit financially from the decision while landowners have an economic incentive to keep pushing, so the pro-development advocates usually outlast the slow-growthers until getting a positive decision.

Local governments can discourage development in some areas by tools other than zoning. Governments can limit access to certain services, for example. In the Rural Area of Prince William County, the Comprehensive Plan states that "Development in the Rural Area shall occur without public sewer facilities, except where provided for in this chapteróto address specific public health concerns or to serve a specific public facility."

Officials can also incentivize development in some places by enhancing transportation services. The classic example is the use of Metrorail services to spur redevelopment of the Rosslyn-Ballson corridor in Arlington County, or the proposed $5 billion plan to extend Metrorail to Dulles through Tysons Corner.

One other tool is in the toolbox of local governments. If they want to shape the evolution of a place... they can buy it.

Acquisition would allow a county/city to exert much more granular controls on growth compared to zoning, by converting a jurisdiction into a powerful public-sector developer in competition with private-sector developers. Many rural communities across the country already develop industrial parks with empty shell buildings,. and then try to find businesses in order to generate local jobs.

Even in wealthy Northern Virginia, no county or city would ever be rich enough or philosophically inclined to purchase all the undeveloped private property within their boundaries. The best examples of local governments acquiring large tracts and then serving as public-sector developers are the attempts by Prince William County to create a high-tech office park at Innovation (site of the GMU campus in the county) and by Fauquier County to convert the Vint Hill Farms Station (a former Army intelligence-gathering site, closed under a Base Realignment and Closure initiative) into a job center.

Prince William County purchased 1,500 acres, built roads and stormwater drainage systems, and tried to attract various companies to build there. By subsidizing the development costs, the county expects to attract high-wage jobs that will stimulate spin-off developments that generate new tax revenues, beyond the costs of developing Innovation.

After abandoning efforts to recruit dot.com technology companies, the county has sought to attract a critical mass of biotechnology and bioinformatics companies. Most of those companies in the DC region are located in Maryland on the Interstate 270 corridor, near the National Institutes of Health. However, the state of Virginia contributed millions in incentives to help Prince William recruit the American Type Culture Collection from Rockville, when that business needed to expand. Virginia has incentivized biotech firms in other regions of the state as well, under the assumption that if enough businesses in the same field locate in the state, a self-sustaining community will develop. GMU and other universities will graduate students who get biotech jobs in the state, and more jobs will generate more taxes to help repay the state's investment.

It's a long-timeframe approach, just like investing in Metrorail in the Rosslyn-Ballston corridor required a long-term perspective. By owning land at Innovation, rather than just providing transportation improvements to incentivize redevelopment, Prince William has geater control over what will be constructed on those 1,500 acres. The county can guarantee that site development will not be delayed, if a company agrees to move to Innovation - and that assurance has helped get the state of Virginia to provide major grants to attract jobs.

However, even the best laid plans can go astray. Economic development is not a business for the faint-hearted; there are major wins and major losses. Eli Lilly made international news when it decided to build a major insulin production facility at Innovation. Then a change in corporate strategy caused the company to halt construction in January, 2007, leaving a half-finished steel skeleton to rust at the intersection of Route 28 and Prince William Parkway. Now a different company (Covance) plans to move from offices in Vienna/Chantilly to use part of the Eli Lilly site, opening a drug development facility there by 2011.

The Vint Hills Farms station was once the largest employer in Fauquier County. The Army has moved out, however. The showcase tenant there now is the Federal Aviation Administration, which is consolidating the radar control centers for the Baltimore-Washington, Dulles, Reagan National and Richmond airports and Andrews Air Force Base. Development at Vint Hill, like Innovation, is less than completely "smart" because the site is far from existing develoment, and far from mass transit services. The only way for people to get to either site is to drive.

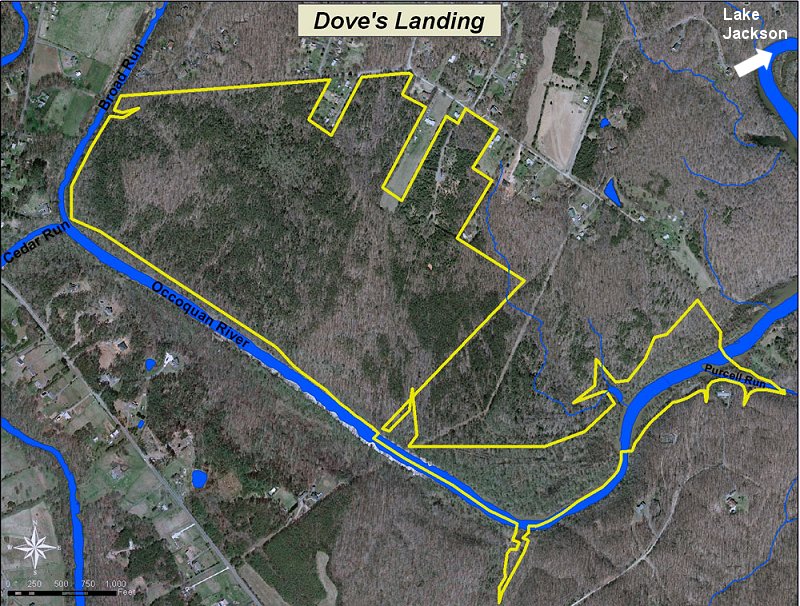

Acquisition of property can also be used to block inappropriate development. The Prince William County Board of Supervisors acquired a 235-acre undeveloped property located along the Occoquan River, upstream from Lake Jackson, in 1996, after a developer tried to force the county to purchase increased public access rights. The county was unwilling to finance the road costs for the benefit of the private developer, and resolved the legal dispute by buying the land. The county has never resold the already-subdivided lots, or made use of the property as a park or school site. Since it was purchased, the "Dove's Landing" property has remained vacant (with a "Keep Out" sign posted at the boundary).

More background:

1) Explore the location of the GMU campus ( (10900 George Mason Circle, acccording to the County Mapper) and the Innovation site on the County Mapper

2) Read:

and, for Vint Hill,

Smart Growth/Sustainable Development in NOVA: More Real Than the Easter Bunny?

Northern Virginia

Virginia Places