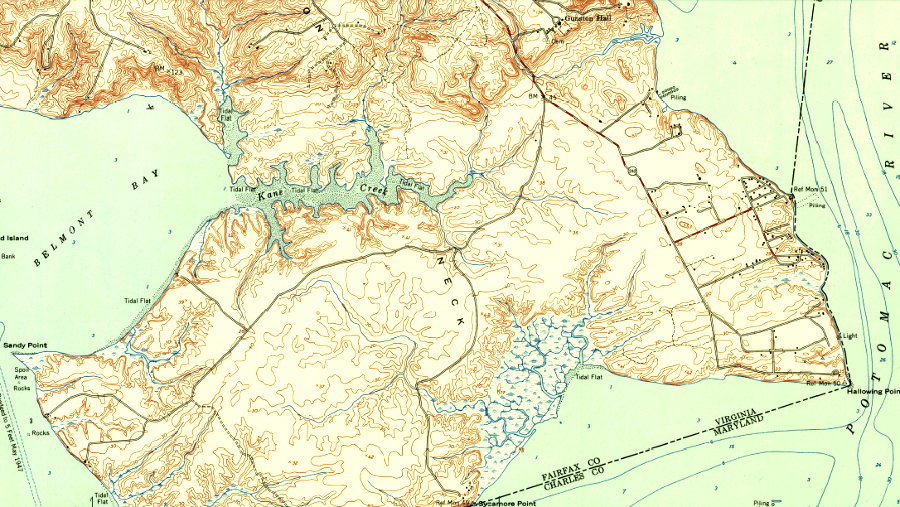

Mason Neck

Source: Terraserver

Mason Neck

Source: Terraserver

"It is no accident that Mason Neck is protected today, nor that its extensive network of public lands is managed by three different levels of government"

Elizabeth Rieben, Safe Landing: Elizabeth Hartwell's Role in Protecting Mason Neck, Virginia, and Its Eagles

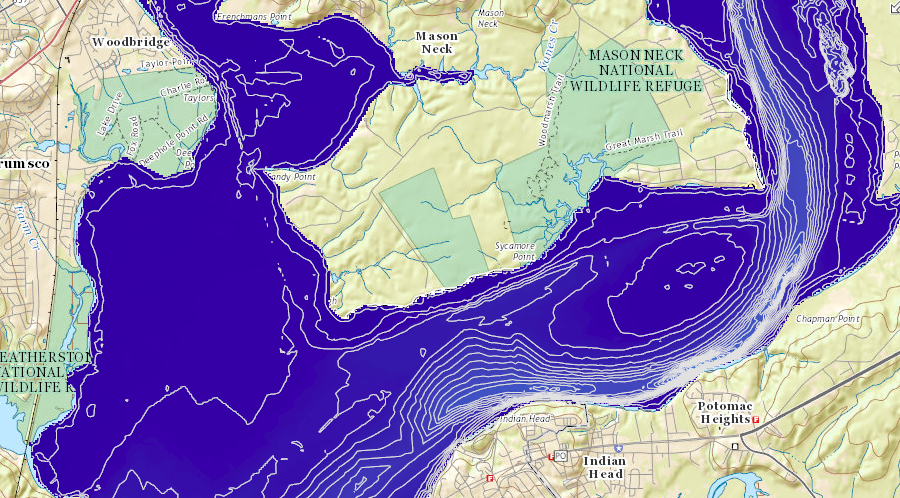

Mason Neck is on the edge of the Coastal Plain, near the Fall Line. Piedmont bedrock is not exposed; local creeks have not eroded below the blanket of soil deposited by marine transgressions in the last 35 million years and by the Potomac River more recently.

There is sufficient clay in the soil that when the District of Columbia built a prison at nearby Lorton, it established a brick-making operation to construct the prison walls, watchtowers, and other buildings.

The peninsula at Mason Neck was formed about 5,000 years ago, when sea levels rose after the end of the last Ice Age. The Potomac River widened and flooded the mouth of the Occoquan River to the south. To the north, the river channel drowned the tip of land separating Pohick and Accotink creeks, isolating the high ground of the peninsula.

The landform has continued to evolve. Sea level rise has drowned the shoreline and the Potomac River has eroded the cliffs on the eastern edge of Mason Neck. The high bluffs visible today may have moved 100 yards further west since the English colonists arrived.1

bricks at Gunston Hall were made from local clay, but the quoins were made of Aquia sandstone from the Government Island quarry in Stafford County

For perhaps the last 15-20,000 years, Native Americans have hunted on the ridge that is now Mason Neck. People have lived there for 13,000 years, though their earliest sites may be underwater now. When the Europeans arrived, the area had been occupied by the Moyumpse people for 350 years.2

where the first humans lived, prior to sea level rise at the end of the Ice Age, is now underneath the Potomac River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

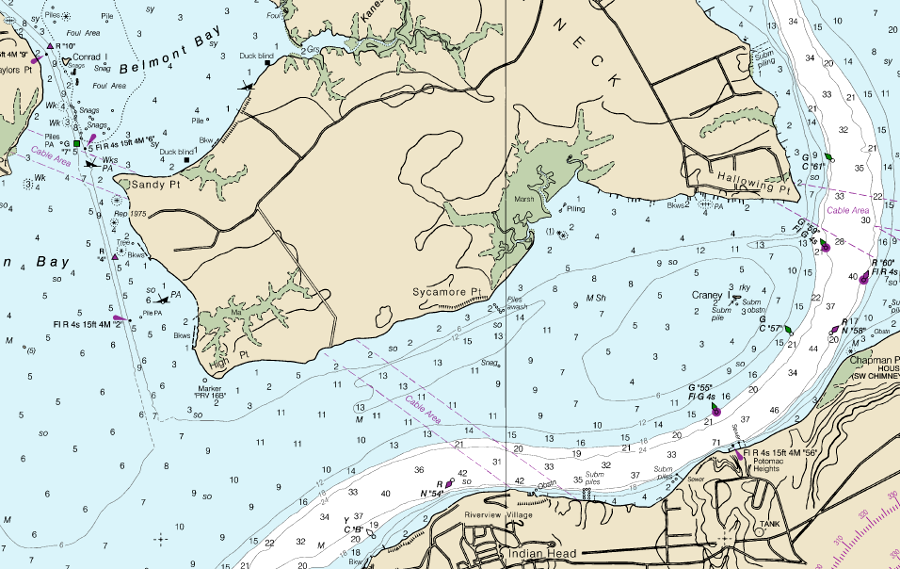

bathymetry of the Potomac River shows the deep channel is near the opposite shore, away from Mason Neck

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Coast Survey Chart 12289

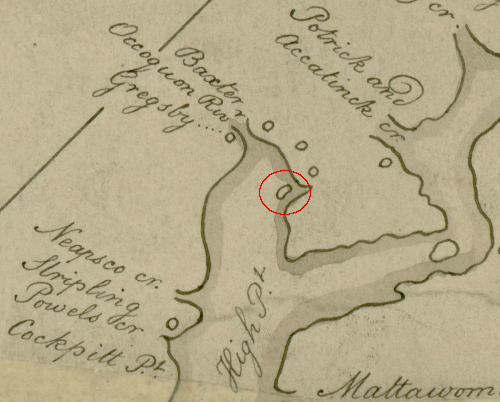

John Smith and his exploration party became the first Europeans to see Mason Neck, in 1608. He recorded that the village at the mouth of the Occoquan River was called Tauxenent, and occupied by the Moyumpse people. Smith relied upon translators from other tribes who described the Moyumpse as the "Doeg." That may have been an uncomplimentary term used by rivals.3

The Native Americans on Mason Neck were probably Algonquian-speaking. They were not part of the paramount chiefdom controlled by Powhatan, with his capital further south at Werowocomoco. The people living on the peninsula in 1608 were associated with the Piscataway who lived across the Potomac River in what now is Maryland. They were subjects of the tayac, the paramount chief in the region, who resided at Moyaone near Piscataway Creek.4

the Moyumpse (Doeg) tribe occupied an island at the mouth of the Occoquan River

Source: University of Pittsburgh, A Map of the northern neck in Virginia by Peter Jefferson and Robert Brooke (1747)

In 1608, an island in Belmont Bay was occupied by the Moyumpse. When Native Americans first arrived, sea levels were far lower and that island have been a peninsula attached to Mason Neck. In the last 400 years the island has disappeared, eroded away by natural forces, but shallow water in Belmont Bay indicates its former location.5

the island at the mouth of the Occoquan River has disappeared due to erosion

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Bathymetry and Digital Elevation Models

John Smith documented the town of the Moyumpse as "Tauxenent," at the mouth of the Occoquan River south of Mason Neck (red X)

(on map, north is to the right)

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia by John Smith (1624)

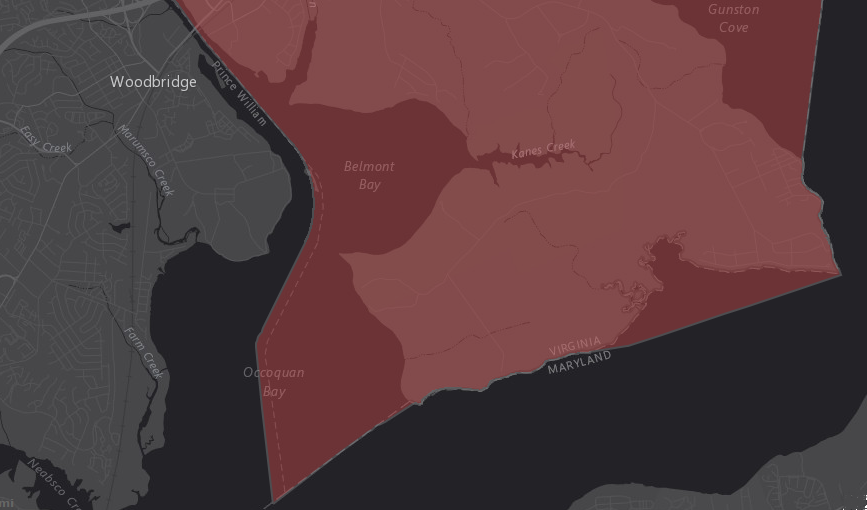

When the colony of Maryland was created in 1632, the charter granted all of the Potomac River to the Calvert family. Virginia and Maryland disputes over rights to the Potomac River have reached the US Supreme Court several times, but the Black-Jenkins arbitration decision of 1877 resolved that the boundary between the states would be the low-water mark on the southern shore of the Potomac River.

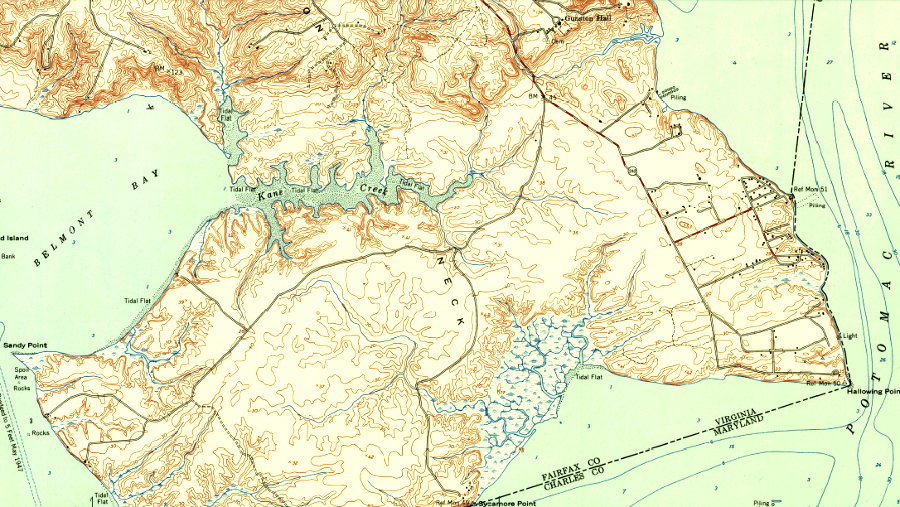

The Matthews-Nelson Survey of 1927 defined a fixed boundary. The line separating the two states was drawn between different headlands extending into the river (such as Hallowing Point), while Gunston Cove and other shallow-water embayments were granted to Virginia.

the Maryland-Virginia border at Mason Neck cuts in a straight line across the mouth of Pohick Creek, then follows the shoreline before cutting in another straight line across an embayment in the peninsula

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Fort Belvoir 7.5x7.5 topographic map (Revision 1, 2013)

some mapping services do not account for the boundary defined by the Matthews-Nelson Survey of 1927

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online (Dark Grey Canvas basemap)

Fairfax County defines its administrative border based on the straight lines created by the Matthews-Nelson Survey of 1927

Source: Fairfax County Open Data, Fairfax County Border

Map: ArcGIS Online

What is known today as the Mason Neck peninsula was patented by land speculators during the 1650's. It was occupied by the Mason family before the end of that century.6

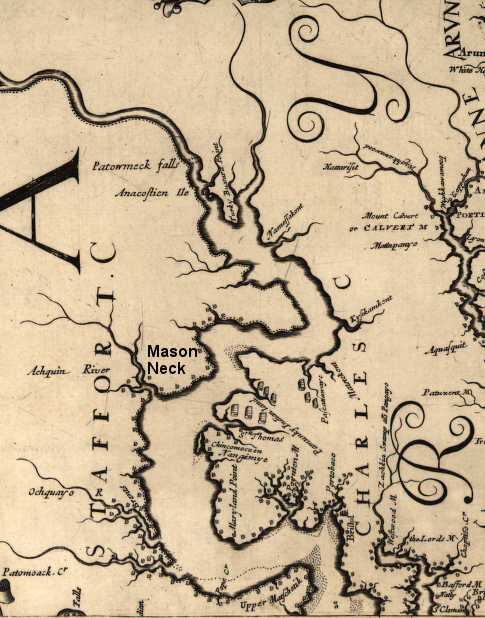

by 1670, colonial settlement was expanding up the Potomac River from the Brents at Aquia Creek (Ochquay), but only Native Americans maintained settlements at what would be named Mason Neck

(map rotated so north is at top)

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 by Augustine Herrman

There were multiple men named George Mason in the family. George Mason IV became famous enough for his role in the American Revolution to get a university in Northern Virginia named after him, and to have his plantation home (Gunston Hall) preserved.

The father of George Mason IV ran a ferry across the river from Hallowing Point to Maryland. He fell into the river and drowned, leaving George Mason IV without a father at the age of 11. George Washington also lost his father when he was 11 years old, while Washington was living at Ferry Farm near Fredericksburg.

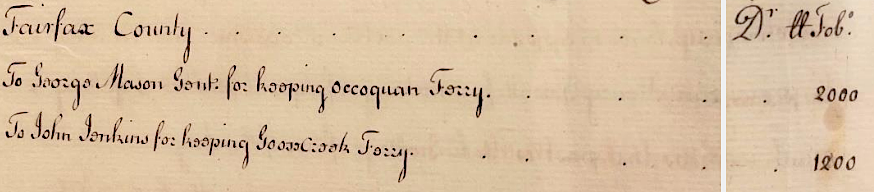

in 1756, Fairfax County paid George Mason IV to maintain the ferry from Mason Neck to Prince William County

Source: Fairfax County Circuit Court, Found in the Archives (October 2022)

Fairfax County regulated the rates which George Mason IV could charge for his ferry crossing the Occoquan River between Colchester-Woodbridge. Fairfax County subsidized that operation in 1756, paying 2000 pounds of tobacco.

Mason Neck in 1864

Source: Library of Congress, Central Virginia (1864)

Mason Neck in 1951

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Fort Belvoir 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle

Like the Washington family, the Mason family used slave labor to grow crops, including tobacco. Though George Mason and George Washington had much in common, they ended up leading separate political factions. Mason feared centralization of power and opposed ratification of the Constitution in 1787, while Washington supported a stronger Federal union and ended up as the first US president. The difference of opinion ended the friendship between the two colonial leaders.7

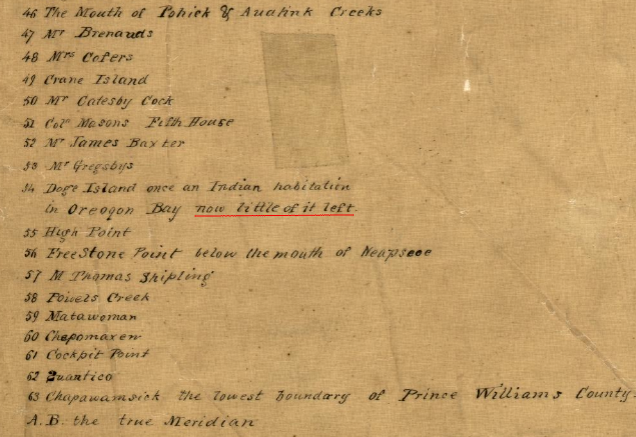

when George Mason IV was born, little of Dogue Island was left according to a map completed in 1737

Source: Library of Congress, A plan of Patomack River, from the mouth of Sherrendo, down to Chapawamsick (by Robert Brooke, 1737)

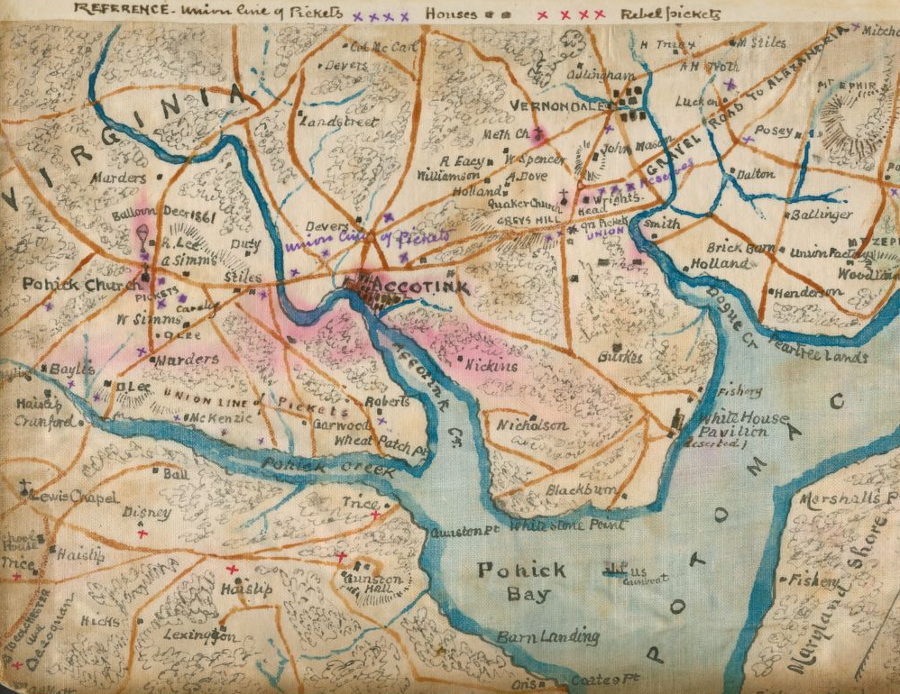

In early 1862 during the winter after First Manassas, Mason Neck was briefly on the front lines of the Civil War. Before the Confederates abandoned their northern defense line in March, 1862 to respond to McClellan's Peninsula Campaign:8

in 1862, the future site of Quantico was undeveloped

Mason Neck in Civil War, when pickets were stationed on opposite sides of Pohick Creek

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the lower Potomac River showing picket lines, January 1862 (by Robert Knox Sneden); Library of Congress, Map of n. eastern Virginia and vicinity of Washington ("McDowell Map," 1862)

After the soil was exhausted on the peninsula, farming was limited and the forests re-grew. After the Civil War, Mason Neck was the home of various sawmills, and primary land use was timber management.

the rail line was built on the northern edge of Mason Neck after the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of fifteen miles around Washington (by G. M. Hopkins) (1878)

In 1912, Louis Hertle purchased Gunston Hall, the plantation house built by George Mason IV in the 1750's and sold by the family in the 1830's. On 1914, he married a woman who was a member of the National Society of Colonial Dames of America. They restored the mansion house to its earlier grandeur, and Louis Hertle donated it to the state of Virginia as a memorial to George Mason (the "Forgotten Founder") when he died in 1949.9

The Board of Regents of Gunston Hall, appointed by the National Society of Colonial Dames of America, manages the site together with a three-person Board of Visitors appointed by the governor. The authority of the state to direct operations became an issue in 2012, when the Regents ultimately fired the museum director after a year of controversy regarding his willingness to work with volunteers and staff. That same year, the Board of Regents adopted a new mission statement for Gunston Hall:10

Gunston Hall, built by George Mason IV between 1755-1759, was donated to the state of Virginia in 1949

George Mason's plantation depended upon slave labor. Like Washington, Mason divided his plantation into a "manor house" farm where he lived and four other farms where crops were raised by slaves directed by overseers. When he wrote the Virginia Declaration of Rights in 1776, the only person in Fairfax County that owned more slaves was George Washington.11

Archeologists have not found the sites where slaves lived on Mason Neck. Unlike Mason's brick mansion house, the slave quarters were wooden structures. Finding them will be a challenge. The only remains today would be stains in the soil, trash pits, nails, and beads or other small personal artifacts.12

Some of the slaves who cooked, cleaned, and provided other services at Gunston Hall lived in the buildings where they worked. George Mason's son John wrote that there were two additional areas where slaves lived near the mansion house. One was east of the mansion, "masqued by rows of large cherry and mulberry trees." The other was also located where the slave housing would not be visible to the Masons:13

the house and gardens (circled in red) have been restored at Gunston Hall, but not the slave quarters

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

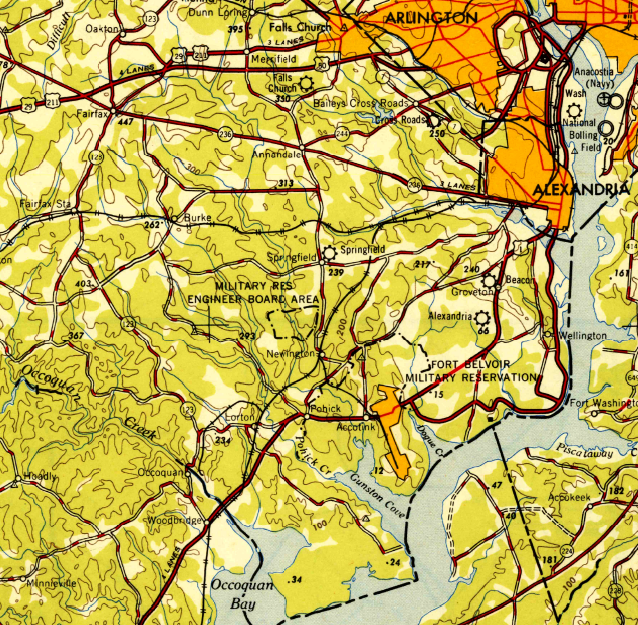

In 1949, VDOT completed the first two lanes of the Henry G. Shirley Memorial Highway (now I-95) to the Occoquan River. It was designed before the start of World War Two as the first major limited access highway in the state, intended to move cars without delays at intersections or driveways. In 1952, the southern end of the Shirley Highway was expanded to become a 4-lane freeway, four years before President Eisenhower initiated the interstate highway system.14

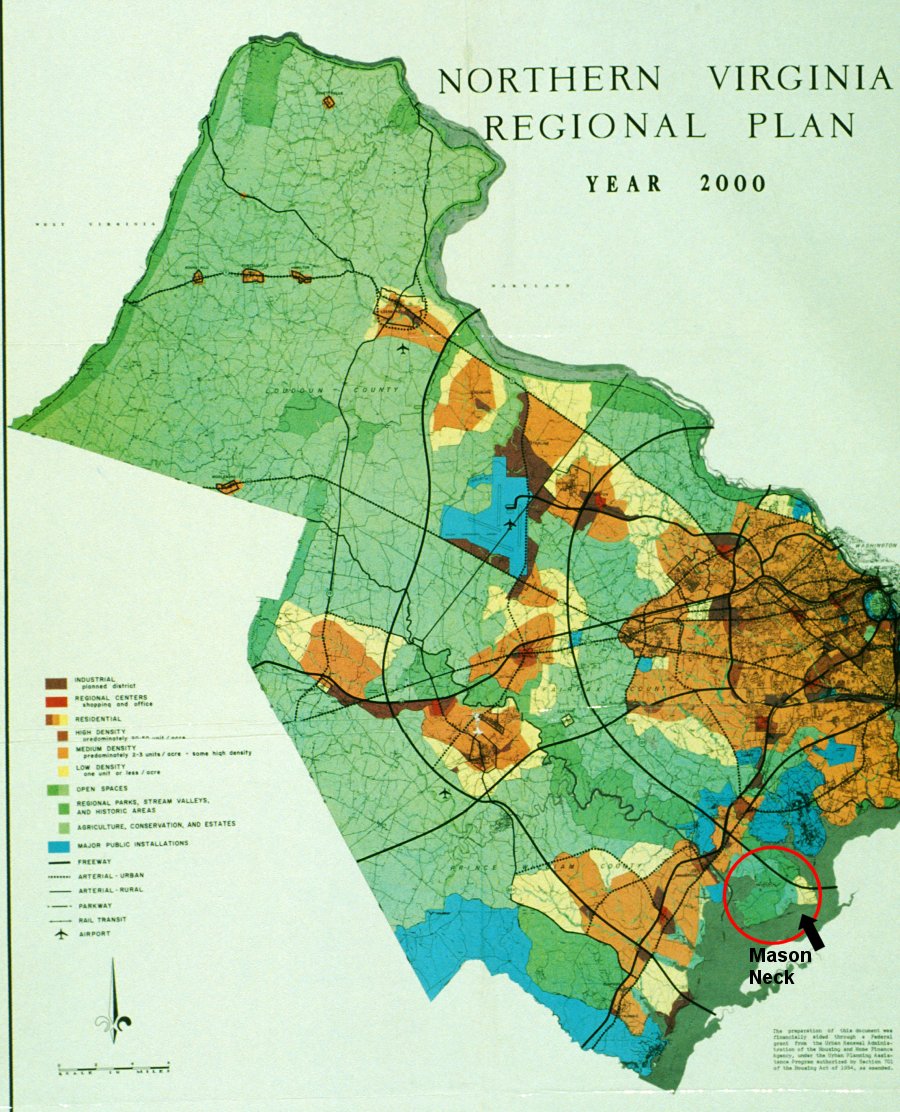

The new highway eliminated the slow commute up Route 1 through Alexandria. Other plans in the 1960's included building two Outer Beltways with a Woodrow Wilson-like bridge over the Potomac River to Maryland, one crossing a Mason Neck and the other bridge crossing the Potomac River at Cherry Hill in Prince William County.

There are no longer any plans for a Potomac River bridge at Mason Neck; that threat to the peninsula has passed, and proposals for a new bridge have moved downstream. The Northern Virginia Transportation Authority continues to propose an East Potomac River Crossing, a bridge from the "Southbridge" development in Prince William County to Charles County in Maryland, in its long-range planning.15

1965 Northern Virginia Regional Plan - projected road network in the year 2000

Not surprisingly, the opening of the Shirley Highway in 1949-52 stimulated rapid population growth in southern Fairfax and eastern Prince William County, just 18-20 miles from the center of Washington. In the 1950's, private property owners near the Shirley Highway got a financial windfall from the new transportation infrastructure. Low-quality farmland become high-value property for building new subdivisions, thanks to the taxpayers who financed the new road. In contrast, the Dulles Greenway extension of the Dulles Toll Road was funded largely by landowners in Loudoun County who would see property values rise, once traffic congestion was reduced.

roads from DC to Occoquan, prior to construction of Shirley Highway (I-95)

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Washington 1x2 topographic quadrangle (1948)

In 1964, two landowners on Mason Neck proposed to sell 1,800 acres they had inherited to a developer that would construct "Kings Landing," a new town like Reston with homes for 20,000 people. In 1966 the Virginia Water Control Board approved a new sewage treatment plant in the Great Marsh, since septic systems could not handle all the expected human waste.16

The peninsula had little residential development in 1964 because local soils had too much clay, and fluids from septic tanks would not percolate or "perc." Large-scale sewage treatment facilities were a recent feature in Northern Virginia. Arlington did not build a sewage plant to treat its waste until 1937, and Alexandria did not open its wastewater treatment plant until 1956.17

Kings Landing, a planned town for 20,000 people

Source: Kings Landing Master Plan, L-K-H, Inc.,1965

reproduced on page 9 in Safe Landing: Elizabeth Hartwell's Role in Protecting Mason Neck, Virginia, and Its Eagles

The planned development included elements supported by "smart growth" advocates. Waterfront property was to be developed at low density, minimizing the impact of construction and the visibility of development along the water's edge. Dense housing would be clustered in the interior of the Mason Neck peninsula. It resembles modern proposals for mixed use projects, where retail development should be surrounded by housing to create a "walkable community" and to facilitate transit by limiting the number of bus stops needed to provide services.

Despite the attractive advertising for Kings Landing, adding 20,000 people to the peninsula would have totally transformed it.

Kings Landing development plan

Source: Kings Landing Master Plan, L-K-H, Inc.,1965,

reproduced in Safe Landing: Elizabeth Hartwell's Role in Protecting Mason Neck, Virginia, and Its Eagles (page 10)

Mason Neck is still largely undeveloped today. A complex of parks, wildlife refuges, and recreation areas protect 6,600 of the 8,000 acres. Residents live without modern amenities such as chlorinated water and sewers, but they also live in a low-density rural setting with horses, eagles, and trails.

That lack-of-development in prime territory for suburban growth did not occur naturally. It required bold action and, at times, unpleasant confrontations between conservationists and developers.

Conservation of land is a contact sport. Developers used to mock the conservation leader who highlighted the value of eagle habitat on Mason Neck at public meetings, by squawking and waggling their arms like chickens. In the middle of the process, eight developers and Fairfax County officials were convicted of bribery related to local zoning decisions.18

What made it possible to conserve Mason Neck was a partnership between Federal, state, county officials and local residents. The Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority was late to the partnership, perhaps in part because one of its board members owned 50 acres he wanted to develop on Mason Neck. At one point, it even abandoned plans to purchase land on Mason Neck and voted instead to accept scenic easements along the Potomac shoreline.19

The Virginia Water Control Board approved the permit for the wastewater treatment plant in 1966. However, the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority became a key player in the modern conservation effort, after the Federal government took the key steps to limit development on the peninsula.

most of Mason Neck peninsula remained undeveloped in 2011

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Fort Belvoir 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2011)

When Kings Landing was proposed on Mason Neck, the Federal government was just ramping up its involvement in conservation. Fifty years ago, in 1958, Congress recognized that the baby boom would stress the existing recreation sites. It created the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission. In 1963, President Kennedy signed the Outdoor Recreation Bill, and the Department of the Interior created a Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. That agency is now defunct, with remnant responsibilities folded into the National Park Service.

One conclusion from the commission's National Recreation Survey was:20

The Land and Water Conservation Fund Act in 1965 finally created a funding source, from revenues generated by leasing offshore oil and gas on the Outer Continental Shelf.

A resident on Mason Neck, Elizabeth Hartwell recognized that the eagles would have be displaced. She mobilized public support to protect the eagles and block the land use changes required for the proposed development.21

In early 1965, the Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall, toured along the Potomac looking for potential conservation sites. Elizabeth Hartwell was not invited, but she crashed the tour to make sure the Secretary understood the opportunity to save the eagles (and their habitat) at Mason Neck. She drove in her personal car behind the official bus, getting out at each stop. It was 1965 and she was wearing high heels, unable to climb to at least one overlook.

Secretary Udall decided the Federal government should get become involved in zoning cases that could result in inappropriate development along the Potomac River, and he wrote directly to the Fairfax County Director of Planning and to the Planning Commission. Armed with political support from President Johnson, who recognized that the Federal government could not ignore the decline of the water quality in the Potomac River, the Secretary was able to play a powerful role in the Mason Neck story. He used his position to express clear support for conserving rather than developing the peninsula - and to steer Federal funds for acquisition of key parcels.

Today, Federal policy is to minimize involvement in local issues, and to minimize land acquisition. Funding is focused on reducing the maintenance backlog for existing Federal properties, rather than obtaining additional property that will increase the maintenance backlog.

Mason Neck in 1951

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Fort Belvoir 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (1951)

Housing developments were not the only threat to Mason Neck. Though it may seem odd today, in 1965 there was a special County Port Committee, created to advocate with the City Alexandria that the Army Corps of Engineers should dredge a deeper shipping channel in the river - funded by Congress, of course.

The committee proposed creating a deepwater port at Belmont Bay, filing in the shallow bay with the sediment dredged up from the channel. The expectation was that industrial development at the port would provide jobs and taxes, though obviously the port facilities would transform the historical and natural environment of Mason Neck.

The logic behind the port proposal? River access is limited, and property along the river should be zoned and developed to maximize the economic potential of river access. Today, the same logic shapes the large amount of land zoned for industrial development along railroad tracks. While places with river/rail access may have value for other land uses, it's pretty hard to move the transportation network - so other places should be zoned to provide the other land uses such as housing, parks, and wildlife habitat.

Elizabeth Hartwell gets much of the credit for convincing Federal, state, and local officials to create a mixture of Federal, state, and regional parks/refuges. However, she did not work alone. She formed the Mason Neck Conservation Committee, which included politicians and savvy activists who know how to generate media coverage and get support. In 1966, the Fairfax Planning Commission created a Lower Potomac Master Plan that endorsed parkland acquisition (4,695 acres) over port/housing development on Mason Neck.

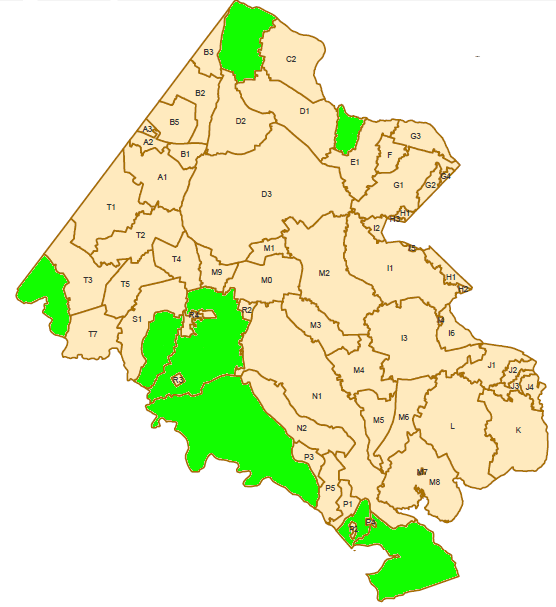

Federal, state, regional, and local agencies protecting land on Mason Neck

Source: Safe Landing: Elizabeth Hartwell's Role in Protecting Mason Neck, Virginia, and Its Eagles (page 90)

Turning that proposal into actual parkland acquisition required money - and a key source was the new The Land and Water Conservation Fund. In addition, Fairfax voters approved a park bond in 1966 that provided funding for expansion of the existing Pohick Bay Regional Park. The non-profit Nature Conservancy stepped in and committed $6 million to purchase properties (including the Kings Landing holdings) to block development, and later recovered its costs by selling the property to government agencies when they had finally obtained funds.

In a creative maneuver, the new Endangered Species Act was cited to justify creating the first National Wildlife Refuge intended to protect an endangered species, the bald eagle. the US Fish and Wildlife Service normally acquired property with revenues paid by hunters - a "Duck Stamp" must be purchased in order to hunt migratory waterfowl. Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge was acquired with funds appropriated by Congress for endangered species, plus Land and Water Conservation Funds.

More recently, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) engaged in a complex land trade with developers of Laurel Hill (for site of the former Lorton prison) to acquire 800 more acres on Mason Neck and establish the Meadowood Special Recreation Management Area. The BLM has used the old horse farm as a site for adopting wild horses and burros, which have been removed from overgrazed Federal lands in the western United States.

western burros, shipped to Meadowood for adoption by customers in the east

Source: Bureau of Land Management

Mason Neck benefitted from being a conservation priority at a time when new funding became available, plus the commitment of individuals who kept pushing steadily to achieve the vision of parkland. In contrast, the battle to conserve Crow's Nest in Stafford County or Merrimac Farm in Prince William County has required carving out money from existing funding sources. Advocates must work even harder to finance acquisition of high-cost land in Northern Virginia, when low-cost properties in southern/southwestern Virginia offer more conservation values per dollar.

In 2007, the refuge was renamed the Elizabeth Hartwell Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge. In 2005, while testifying in support of the new name, a Federal official summed up the success of the conservation partnership that protected the southeastern corner of Fairfax County:22

as an individual, Elizabeth Hartwell had the greatest influence shaping development at Mason Neck

Source: Elizabeth Hartwell Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge, Elizabeth Hartwell

Since the 1950's, most of Fairfax County has been transformed by suburban development. County officials have re-planned and re-zoned areas to permit increased density, overcoming objections by current residents who desired to maintain their traditional rural lifestyle - or responding to the desires of landowners to increase the value of their land.

Fairfax County then struggled to build roads, schools, drinking water/wastewater capacity, and other infrastructure to meet the demands of new residents scattered across the county. By the start of the 21st Century, the county began to revise its approach to incentivize transit-oriented development, permitting high-rise development at Metro stations and revitalizing old neighborhoods and commercial districts by adding streetcar lines.

Mason Neck avoided that fate. Residents were able to maintain their isolated subdivisions, by blocking plans to add roads or sewers. Without infrastructure, developers saw minimal opportunity to make profits. Transfer of development rights to Laurel Hill at Lorton, and establishment of the Meadowood Special Recreation Management Area in pace of a housing subdivision, finalized the last attempt to increase density on Mason Neck.

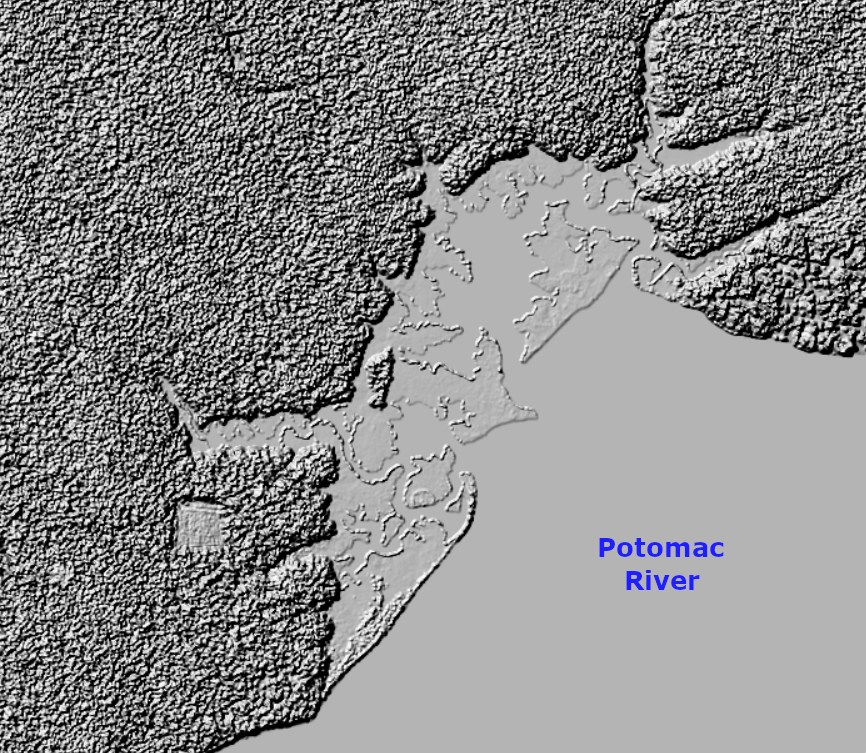

LIDAR reveals the topography of Mason Neck's Great Marsh, on the edge of the Potomac River

Source: Fairfax County, LiDAR Digital Surface Model -2018

Two large areas in Northern Virginia have managed to ensure long-term, low-density development: the downzoned area in Fairfax County near the Occoquan Reservoir, and Mason Neck. In addition, three small segments do not have public sewer services in their "sewershed." The cost of extending sewerlines and installing pumping stations to move the wastewater over watershed divides would be high, providing some assurance that current low-density zoning will not be modified in those sewersheds.

Some low-density areas remain in nearby Prince William and Loudoun counties. According to smart growth concepts, taxes can be minimized if public services are concentrated in certain areas and minimized in other areas. However, Prince William and Loudoun residents living in areas currently planned for low-density development are threatened by the potential for revisions in existing land use plans. New roads and extension of public/water/sewer could transform those areas in the next 20 years, if elected officials alter Comprehensive Plans and zoning ordinances.

The boundary separating the Rural Area and the Development Area in Prince William was adjusted to permit more density (particularly the Avendale development on Route 28 near Bristow), until the Board of County Supervisors eliminated the growth boundary in 2022 and planned for more residential development further away from the urban core. Construction of a road between I-66 and Dulles International Airport, in the North-South Corridor of Statewide Significance designated by the Commonwealth Transportation Board, could trigger rezoning of the Rural Area west of Manassas Battlefield National Park and the Transition Area in Loudoun County, south of Route 50.

some portions of Fairfax County (shown in green) have no public sewer services

the Town of Clifton and a portion of Mason Neck have pump-and-haul services, where wastewater is collected and transported by truck to a wastewater treatment plant

Source: Fairfax County Demographic Reports (2011)

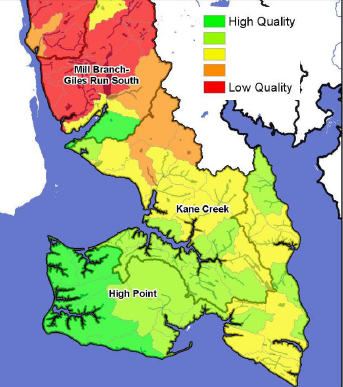

water quality on the undeveloped peninsula is far better than the area transected by I-95

Source: Lower Occoquan Watershed Management Plan (Map 3.5-1)

complex pattern of parkland ownership on Mason Neck

Source: Fairfax County Map Gallery

1. "Elizabeth Hartwell Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge and Featherstone National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan,", US Fish and Wildlife Service, September 2011, p.F-1, p.F-2, https://www.fws.gov/northeast/planning/MasonNeck_Featherstone/pdf/finalccp/14w_Appendix_F_Archaeological_and_Historical_Resources_Overv.pdf (last checked August 20, 2017)

2. Paul Inashima, "Commemorating the David Site (44FX2634)," Archeological Society of Virginia Newsletter, Number 199 (December 2010), p.7, http://www.archeologyva.org/PDF/ASVNL10-12.pdf; Shirley Scalley, "Huntley Meadows Park," http://www.historygems.com/ (last checked August 20, 2017)

3. "Shedding Light on Early History," Fairfax Connection, January 11, 2006, http://www.connectionnewspapers.com/news/2006/jan/11/shedding-light-on-early-history/ (last checked May 22, 2015)

4. Alex J. Flick, Skylar A. Bauer, Scott M. Strickland, D. Brad Hatch, Julia A. King. "...a place now known unto them:" The Search for Zekiah Fort, St. Mary's College of Maryland, 2012, pp.11-14, https://www.academia.edu/2484589/_A_Place_Now_Known_Unto_Them_The_Search_for_Zekiah_Fort_by_Alex_J._Flick_Skylar_A._Bauer_Scott_M._Strickland_D._Brad_Hatch_and_Julia_A._King (last checked November 18, 2016)

5. Robert Morgan Moxham, "The Colonial Plantations of George Mason," 1975, http://www.gunstonhall.org/georgemason/landholdings/moxham.html (last checked August 20, 2017)

6. Robert Morgan Moxham, "The Colonial Plantations of George Mason," Gunston Hall, 1975, http://www.gunstonhall.org/georgemason/landholdings/moxham.html (last checked August 20, 2017)

7. Peter R. Henriques, "An Uneven Friendship: The Relationship between George Washington and George Mason," he Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 97, Number 2 (April 1989), p.185, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4249070; "Found in the Archives" Fairfax County Circuit Court, Number 79 (October 2022), https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/circuit/historic-records-center/newsletter

(last checked October 11, 2022)

8. Susan Schulten, "Mission to Mason Neck," New York Times, February 24, 2012, http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/02/24/mission-to-mason-neck/ (last checked March 18, 2013)

9. "Louis Hertle, 1860-1949," Gunston Hall, http://www.gunstonhall.org/index.php/mansion/hertle (last checked February 10, 2016)

10. "Gunston Hall Annual Report, 2012," National Society of The Colonial Dames of America, http://www.gunstonhall.org/docs/Annualreport2012B2.pdf; "Gunston Hall," "Gunston Hall Museum Director Ousted by Regents After Year of Controversy," The Connection, April 19, 2012, http://www.connectionnewspapers.com/news/2012/apr/19/gunston-hall-museum-director-ousted/; Virginia Historical Society, http://www.vahistorical.org/collections-and-resources/garden-club-virginia/plantations/gunston-hall (last checked February 10, 2016)

11. "George Mason's Views on Slavery," Gunston Hall, http://www.gunstonhall.org/georgemason/slavery/views_on_slavery.html (last checked August 20, 2017)

12. "An Interview with the Staff Archaeologist," Gunston Hall, August 8, 2013, http://gunstonhallblog.blogspot.com/2013/08/an-interview-with-staff-archaeologist.html (last checked August 20, 2017)

13. quoted by David B. Shonyo, "Archaeological Investigations At Gunston Hall Plantation (44FX113) - Report on 2013 Activities," Gunston Hall Plantation Archeology Department, March 2014, p.17, http://www.gunstonhall.org/docs/Gunston-Hall-Arch-2013.pdf (last checked August 20, 2017)

14. "Henry G. Shirley Memorial Highway," Roads to the Future, http://www.roadstothefuture.com/Shirley_Highway.html (last checked August 20, 2017)

15. "TransAction Plan Project List - Draft for Public Comment," Spring/Summer 2017,

Northern Virginia Transportation Authority, p.121, http://nvtatransaction.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/NVTA_TA_Project-List_Draft-v8.pdf (last checked August 20, 2017)

16. Elizabeth Townsend Rieben, "Safe Landing - Elizabeth Hartwell's Role in Protecting Mason Neck, Virginia, and Its Eagles," Masters Thesis at Virginia Tech, 2007, p.46, http://masonneck.org/docs/Safe_Landing.pdf (last checked August 20, 2017)

17. "When an Outhouse Isn't Enough - Arlington Gets a Wastewater System," Arlington County, January 10, 2012, https://environment.arlingtonva.us/2012/01/outhouse-isnt-enough-arlington-gets-wastewater-system/; "History," AlexReNew, https://alexrenew.com/about-alexrenew/our-history (last checked August 20, 2017)

18. "John P. Parrish, 88; Figure In '60s Fairfax Bribe Case," Washington Post, April 24, 2008, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/04/23/AR2008042303552.html (last checked August 20, 2017)

19. Elizabeth Townsend Rieben, "Safe Landing - Elizabeth Hartwell's Role in Protecting Mason Neck, Virginia, and Its Eagles," Masters Thesis at Virginia Tech, 2007, pp.44-48, http://masonneck.org/docs/Safe_Landing.pdf (last checked August 20, 2017)

20. "Outdoor Recreation for America - ORRC Report, 1962," National Park Service, http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/anps/anps_5d.htm (last checked April 16, 2008)

21. "'Eagle Lady' Cited For Wildlife Refuge Work," Washington Post, October 25, 1990, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1990/10/25/eagle-lady-cited-for-wildlife-refuge-work/95fa01f8-296c-4b2c-aac1-3f60691daebf/ (last checked August 20, 2017)

22. "Testimony Of Rick Schultz, Chief Of The Division Of Conservation, Planning, And Policy For The National Wildlife Refuge System, United States Fish And Wildlife Service, Department Of The Interior, Before The Subcommittee On Fisheries And Oceans Of The House Committee On Resources, Regarding H.R.2866, Providing For The Expansion Of The James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge, Honolulu County, Hawaii, And H.R.3682, Redesignating The Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge In Virginia As The Elizabeth Hartwell Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge," December 6, 2005, http://www.fws.gov/laws/testimony/109th/2005/Shultz_testimony_12-106-05.html (last checked April 16, 2008)

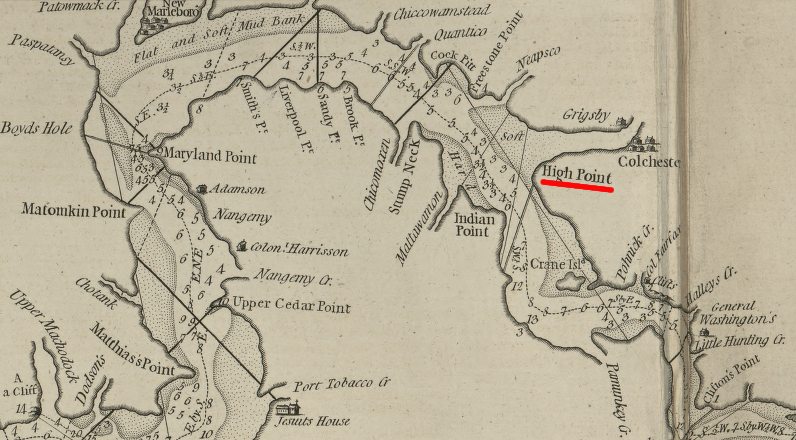

on this 1777 navigation map, High Point on Mason Neck was highlighted

Source: Library of Congress, The North-American pilot for New England, New York, Pensilvania, Maryland, and Virginia; also, the two Carolinas, and Florida

an eroding cliff was labeled as High Point, while a marsh was identified as Low Point

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the state of Virginia, constructed in conformity to law from the late surveys authorized by the legislature and other original and authentic documents (1859)