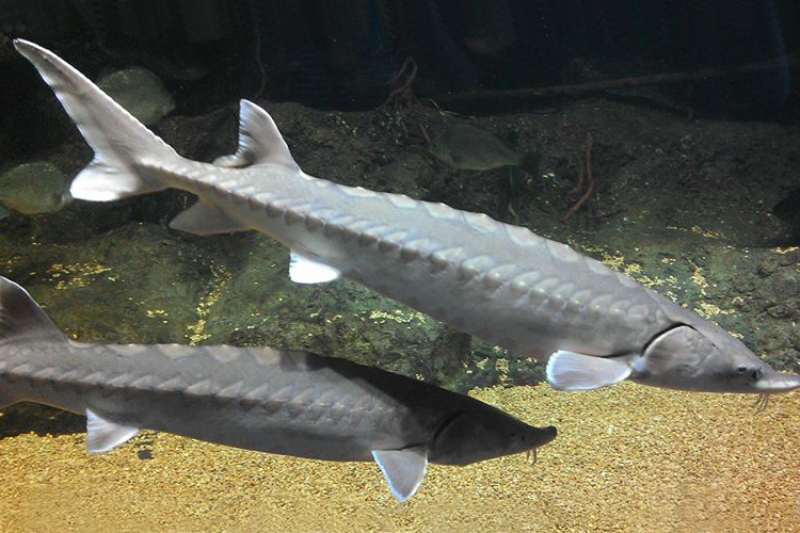

Atlantic sturgeon have five rows of bony plates (scutes) rather than scales

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Atlantic Sturgeon

Atlantic sturgeon have five rows of bony plates (scutes) rather than scales

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Atlantic Sturgeon

The National Marine Fisheries Service has the lead role in managing the endangered Atlantic sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus) and shortnose sturgeon (Acipenser brevirostrum) populations. The anadromous fish hatch in freshwater rivers and stay there for one-six years. Atlantic Sturgeon live their adult lives in the saltwater Atlantic Ocean, then migrate back to rivers to spawn. Shortnose sturgeon spend little time in the ocean, staying in brackish estuaries instead.

The sturgeon family evolved at least 120 million years ago. The modern Atlantic Sturgeon species has been in existence for 70 million years; the fish swam in Virginia rivers while dinosaurs roamed on the land. Unlike dinosaurs, sturgeon survived the impact of the Chicxulub asteroid 66 million years ago. Sturgeon were spawning in 38 rivers in eastern North America when humans arrived roughly 20,000 years ago.

To grow as large as 14 feet long, sturgeon use barbels on their snouts to identify food on a river bottom or continental shelf and then vacuum it into their mouths. An individual Atlantic sturgeon can live as long as 60 years and grow up to 600 pounds, but fish today live about half that lifespan and reach weigh half of that weight.

The Atlantic sturgeon invaded and colonized the Baltic Sea during the Middle Ages, displacing the native species (Acipenser sturio) which had evolved since the North Atlantic Gyre formed 15-20 million years. The European populations have been extirpated since then.

The species has survived in North America, but at much reduced levels. Sturgeon were overharvested after the Civil War to obtain the eggs, eaten as a form of caviar. In addition to the "Black Gold Rush," habitat loss also reduced the population. In 2012 the Atlantic sturgeon was added to the list of species protected under the Endangered Species Act.

Today, there are nine sturgeon species and subspecies in the United States. Shortnose sturgeon (Acipenser brevirostrum) are very rarely seen in Virginia waters or the Potomac River. Between 1996-2012, only 93 shortnose sturgeon were seen in the Chesapeake Bay area compared to 1,590 Atlantic sturgeon.

Atlantic sturgeon caught in the Chesapeake Bay

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Atlantic Sturgeon

The Atlantic Sturgeon still spawns in 22 rivers in eastern North America. The species has five distinct population segments between Main and the Gulf Coast, including the Chesapeake Bay population segment that lives in Virginia waters. The Chesapeake Bay population and three other distinct populations are listed as "endangered" by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The population in the Gulf of Maine is listed as "threatened."1

Sturgeon are anadromous fish, spawning in freshwater but living their adult lives in saltwater. Adults spawn in the Tidewater rivers near the Fall Line, where the bottom of the river had exposed hard rock not covered with slit or mud.

After two-three years, the young sturgeon in Virginia rivers migrate downstream to the Chesapeake Bay and swim into the Atlantic Ocean, where they live the remainder of their adult lives except for spawning runs.

The reproductive capability of the sturgeon population is limited. The long-lived male sturgeon does not reproduce for its first 10 years of life, and the process starts even later for females. In addition, females do not return to freshwater to spawn every year. Instead, they skip one or two years.2

Sturgeon were a major food fish for the Native Americans before colonization. They used brush dams and weirs that let the fish enter side streams at high tide, but trapped the sturgeon at low tide. A mature fish could be six feet long, and a rite of passage for a young Pamunkey male was to catch a ride on the back of a fish.

After the Richmond and York River Railroad was completed in 1859, the Pamunkey shipped commercial quantities of caviar to Richmond and northern markets. By then drift nets were preferred to catch the fish. Robert Beverley reported in 1705 on the traditional harvest method:3

Source: Melissa Lesh, James River Sturgeon

The English colonists at Jamestown learned from the Native Americans how to catch sturgeon for protein in August-October. In the 1800's, they were advertised for sale as "Charles City Bacon."

The practice of catching females and salting their eggs to create caviar became common. Overfishing for sturgeon eggs (caviar), together with habitat loss due to pollution and dams, caused a dramatic population decline. The peak harvest of 7,382,000 pounds on the Atlantic coast in 1890 dropped in three decades to just 100,000 pounds.

The last legally-harvested sturgeon was caught in 1970. Virginia banned the harvest of sturgeon in 1974, and biologists questioned if the sturgeon were about to go extinct. When the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission imposed a regional moratorium on fishing for the species in 1997, there were no known breeding areas in a Virginia river. After one sturgeon was caught in 1997, a fisheries biologist conmented:4

The conventional wisdom was disrupted in 2014, when a sturgeon 5.5 feet long jumped into a boat in Marshyhope Creek. That stream is a tributary to the Nanticoke River on Maryland's Eastern Shore. Two retired U.S. Department of Agriculture scientists got a picture, providing solid evidence. Other biologists seeking to find more sturgeon were less successful, but confident they were present.

One said:5

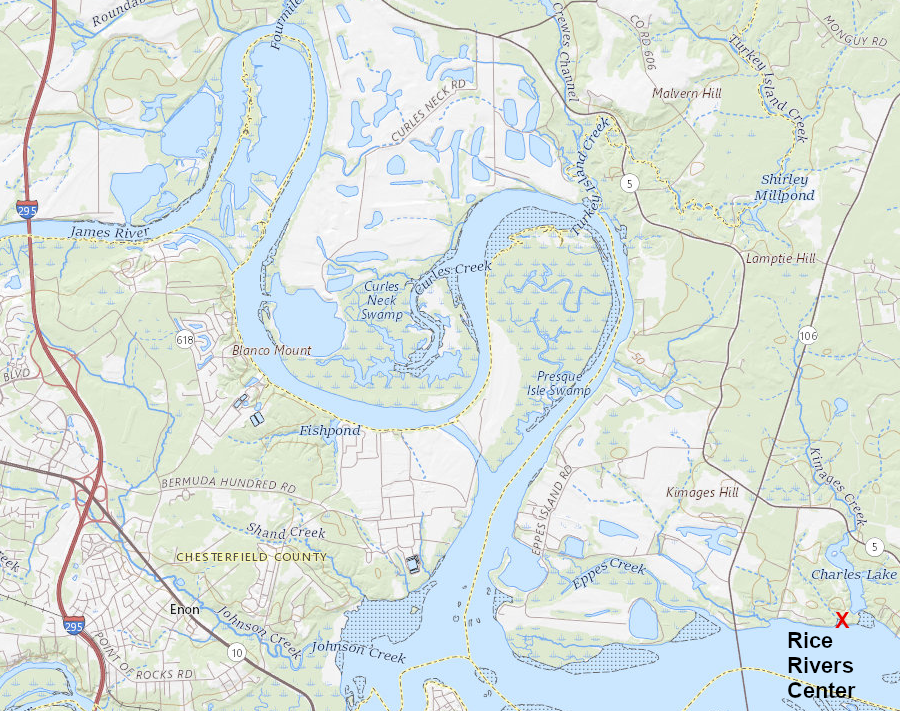

After watermen realized scientists seeking information would not limit their ability to fish for other species, the data on "bycatch" revealed that sturgeon were still spawning in the James River, the Pamunkey, and in a tributary of the Nanticoke River on the Eastern Shore. Researchers at the Rice Rivers Center of Virginia Commonwealth University, located at the mouth of Kimages Creek in the middle of sturgeon spawning habitat on the James River, have caught and tagged over 800 sturgeon.

The research proved that the fish spawn in both the Spring and the Fall. As part of the effort to restore the species, artificial spawning reefs with hard bottoms were constructed in the James River at Presquile National Wildlife Refuge, at Jones Neck, and downstream of the I-295 bridge.

Spawning sites have been identified now in the James and the Pamunkey rivers, and the fish may also spawn in the Mattaponi River. Downstream from the town of West Point at the headwaters of the York River, the water is too salty.6

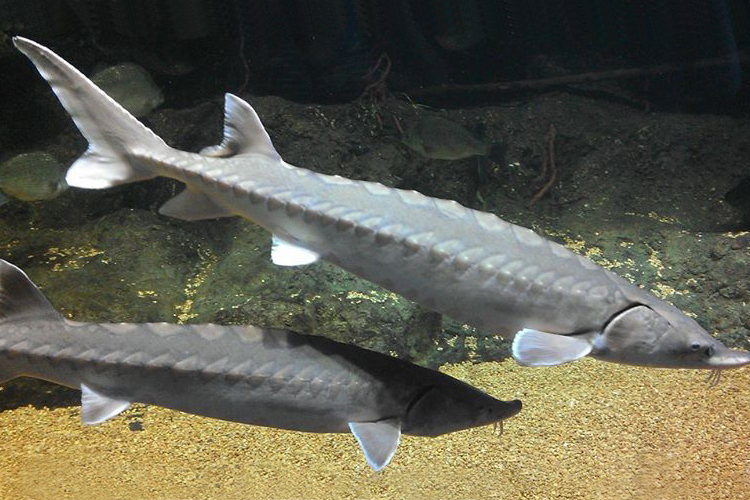

sturgeon prefer to swim near the bottom of rivers

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries, Supporting Endangered Atlantic Sturgeon in the Chesapeake Bay

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) awarded a three year grant to the Pamunkey tribe in 2018 to study sturgeon and their habitat. The project included the capture and release of tagged fish, analysis of DNA, and collection of water quality data.7

There are both Spring and Fall spawning runs, where females swim upriver and males follow. Males that have begun to return to the Atlantic Ocean may turn around and swim back to a spawning site. A Virginia Commonwealth University study in 2021 documented sturgeon swimming an average of 132 to 522 miles a year during spawning runs in the James River.8

By 2023, research had revealed that most Chesapeake Bay sturgeon were spawning in the Fall and that the fish were swimming much further up narrow channels than anticipated. Ship strikes were the major threat to adult fish:9

three artificial reefs for sturgeon spawning have been constructed in the James River between the Rice Rivers Center and the I-295 bridge

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Atlantic sturgeon have five rows of bony plates (scutes)

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Atlantic Sturgeon