freshwater mussels reproduce by releasing glochidia, which attach to the gills or fins of a suitable host fish and get transported to new habitat

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Extracting glochidia from freshwater mussel

freshwater mussels reproduce by releasing glochidia, which attach to the gills or fins of a suitable host fish and get transported to new habitat

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Extracting glochidia from freshwater mussel

In freshwater, mussels are the equivalent of marine clams. They are the longest lived invertebrates in Virginia, with adults living up to 100 years in some species. Of the 1,000 freshwater species in the world, about 1/3 live in North America. The largest number of freshwater mussel species are concentrated in the southeastern states, primarily in the watersheds of the Tennessee and Mobile rivers.

Like clams and oysters, mussels are filter feeders who pump water through their shells and extract food. They live in water that moves. Freshwater mussels prefer river riffles; saltwater mussels chose shorelines and shallows with wave action.

A distinctive feature is the "byssus," proteins which mussels secrete to attach to underwater surfaces.

mussels produce threads of protein which do not dissolve underwater, creating a "byssus" that glues the shell to a hard substrate

Source: Wikipedia, Ischadium

Being sessile and long-lived exposes mussels to pollutants in the water during their long lives. The decline of mussel populations is a clear indicator of the decline of water quality.1

survival of endangered purple bean mussels (Villosa perpurpurea) is tracked by tagging individual mussels

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Purple bean mussels with tags before release in Indian Creek, Tazewell County, Virginia

Adult mussels remain in one spot on the riverbed, though they can change positions slightly by making a new attachment and releasing the old byssus. Unlike fish, mussels do not move to actively seek food. They depend upon water currents to provide a constant supply of phytoplankton and zooplankton, which the mussels filter out for a meal.

To occupy new habitat, freshwater mussels in Virginia rely upon fish to transport larvae to uoccupied habitats upstream. Without fish for larvae transport, mussel beds would gradually migrate downstream and eventually disappear.

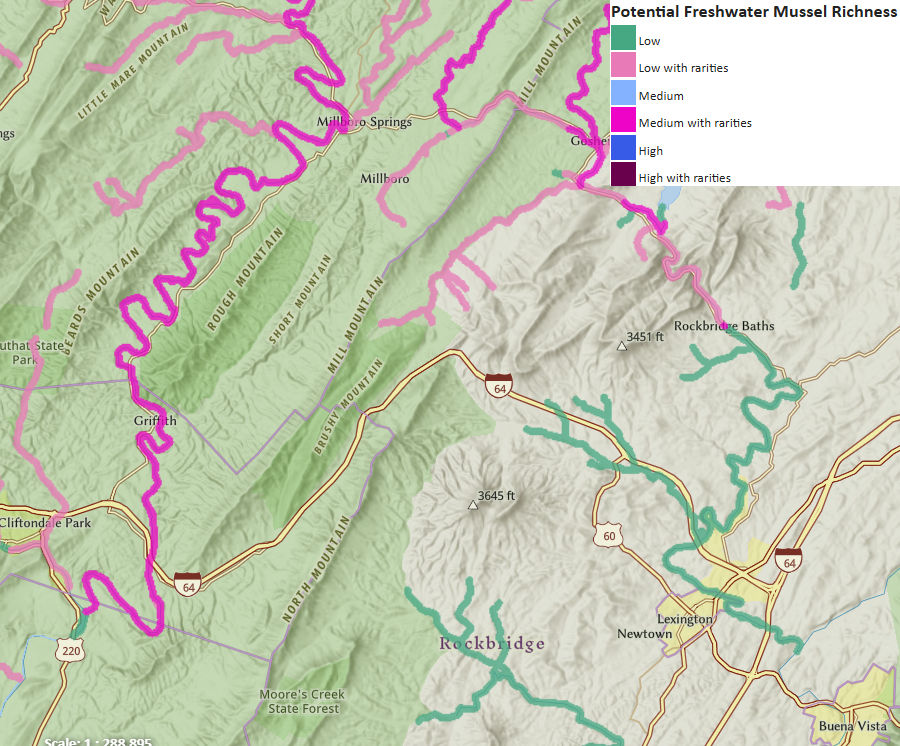

different river segments offer mussel habitat of different value

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), Virginia Natural Heritage Data Explorer

The freshwater mussel reproduction process is distinctive. Unlike saltwater mussels, they do not produce free-swimming veliger larva that are distributed by drifting with the currents.

In freshwater, female mussels lay their eggs in specialized chambers in their gills known as marsupia. Males release sperm into the water, and downstream females pull it into the marsupia through siphons on their gills. The eggs grow into larvae known as glochidia. Those are released into the water where they can parasitize a passing fish, clamping onto the fish gills, fins, or scales and feeding on the fish's body fluids.

Glochidia will stay with a fish for as little as 10 days, or over an entire winter, before dropping out of the fish. If they land on suitable habitat, typically a hard surface on the bottom of a stream where running water will provide fresh food and oxygen, the mussel will grow its byssus and remain in that place for its lifetime.

Some species of freshwater mussels release larvae as packages which attract fish, by resembling what they eat:2

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Endangered Mussels Released into the Clinch River, Largest Release in Eastern US

Virginia has about 80 species of mussels, but that number could drop. The US Fish and Wildlife Service declared the green-blossom pearlymussel to be extinct in 2021, and:3

The Clinch River has more endangered species than any other river in the United States. One of the most significant kills of endangered species since passage of the Endangered Species Act in 1973 occurred when a tanker truck overturned in 1998 on U.S. Route 460. The accident in Tazewell County spilled a chemical which flowed into the Clinch River and killed tan riffleshell, purple bean, and rough rabbitsfoot mussels, which are three endangered species.4

Source: Virginia Museum of Natural History, Freshwater Mussel Restoration in Virginia and the South River Watershed

endangered freshwater mussels in the Clinch and Powell River watersheds (Bottom diagonal row, left to right: Cumberlandian combshell, Oyster mussel. Middle Row: Shiny pigtoe, Birdwing pearlymussel, Cumberland monkeyface. Top row: Rough rabitsfoot)

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Endangered freshwater mussels

Mussel restoration projects depend upon two state and one Federal hatcheries. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources has a propagation facility in Marion, the Aquatic Wildlife Conservation Center (AWCC), while Virginia Tech operates a Freshwater Mussel Conservation Center (FMCC) in Blacksburg. The US Fish and Wildlife Service raises mussels for transplanting into rivers at the Harrison Lake National Fish Hatchery in Charles City County.5

biologists labeled endangered mussels before planting them in the Powell River, so their survival and growth could be tracked later

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Endangered mussels bound for the Powell River and Team of volunteers, students, and biologists release mussels

in Prince William County, mussel restoration has been proposed to enhance completed stream restoration projects that reduced transport of sediment to the Chesapeake Bay. On behalf of the county, the Northern Virginia Regional Commission (NVRC) won a $75,000 grant from the National Wildlife Federation's Chesapeake WILD program. Mussels will be provided by the Harrison Lake National Fish Hatchery of the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the George Mason University (GMU) Potomac Environmental Research and Education Center (PEREC) agreed to administer the program:6

habital model of potential freshwater mussel richness pinpoints where to focus additional mussel surveys and reintroduction efforts

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Natural Heritage Program, Virginia Natural Heritage Data Explorer

to plan for stream restoration, a small number of hatchery reared mussels are placed in baskets to monitor growth and survivorship rates

Source: Prince William County, Power of Partnership: NVRC Secures $75k for Prince William County Stream Filtration Project

biologists found numerous dead pheasantshell mussels at Sycamore Island, when inspecting the Clinch River in 2019

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Richard shows mussels

dead freshwater mussels collected by biologists from the Clinch River at Sycamore Island in 2019

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Dead mussels