Monarch butterfly

Source: National Park Service

Monarch butterfly

Source: National Park Service

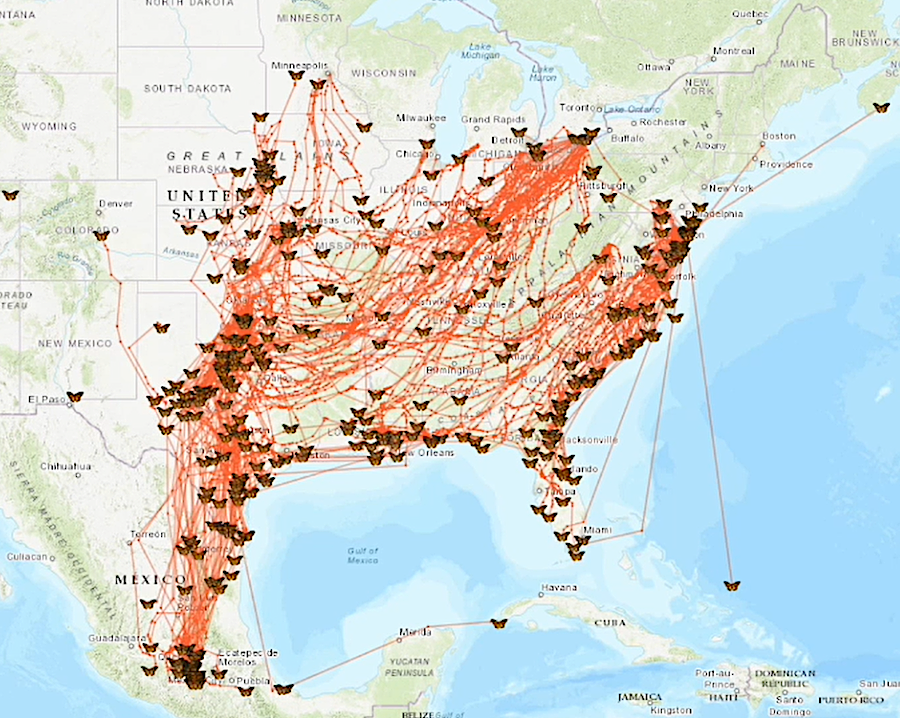

Monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) visit Virginia in the Summer and Fall, then fly out of the state. At least some migrate all the way to Mexico, where they spend the winter. Since 1996, the Virginia Living Museum has tagged and released over 1400 migrating adults. In February 2001, one was discovered in Mexico. In October 2008, another was photographed in Austin, Texas during its journey south.1

A special effort is underway to save the two migrating populations of the monarch butterfly which overwinter in California and Mexico. It expands its range seasonally from Mexico into Virginia and across North America. The only other insect known to make an equivalent long annual migration is the bogong in Australia.

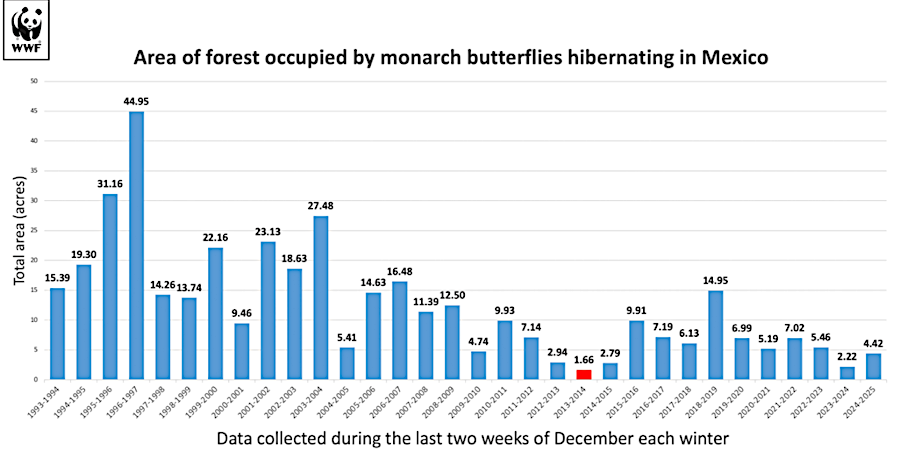

The monarch population that migrates from wintering grounds in Mexico to the Northeast declined by 80% after the mid-1990's, dropping to only 200 million in 2018. The population that wintered in Monterey and Pacific Grove, California and migrated into the Pacific Northwest dropped by 98%, from 1.2 million to just 30,000.

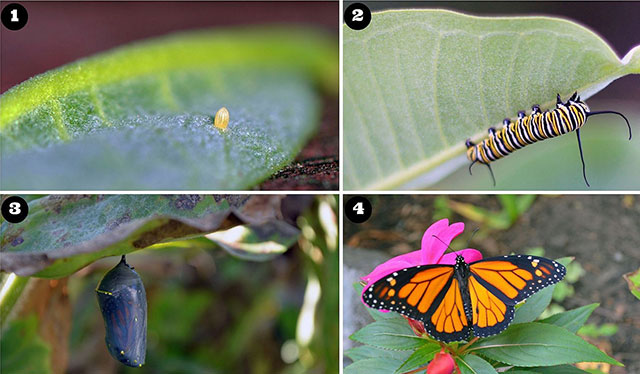

Monarch butterflies transition from eggs to caterpillar, then metamorphose in a chrysalis into a butterfly

Source: National Park Service, Monarch Life Cycle

Between 1993-2001, an average of 8.7 hectares (21.5 acres) of trees were occupied by overwintering monarchs in Mexico. Between 2002-2011, that dropped to 5.7 hectares (14 acres). Between 2011-2021, the size of the forest occupied in the winter dropped even further to 2.62 hectares (5.5 acres).

Source: Nature (on PBS), Inside a Monarch Swarm

In December 2020, the US Fish and Wildlife Service determined that monarch butterflies qualified as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. There was a 10% chance of the main population which migrated to Mexico going extinct in the next 10 years, and a 60-68% chance of the western population migrating to California going extinct within that time.2

However, the Federal agency announced that listing was "warranted but precluded" by lack of resources. The US Fish and Wildlife Service planned to focus on higher-priority species. The International Union for Conservation of Nature officially designated the species as "endangered" in 2022, due to the 20-90% population decline over several decades. Resource constraints were less relevant to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, while the US Fish and Wildlife Service would be responsible for work such as creating a restoration plan and designating critical habitat.

However, after biologists challenged the population models used to make the decision, the International Union for Conservation of Nature reversed its decision to designate the species as "endangered." The models had not considered the possibility that in the 1900's, monarch butterfly populations were abnormally high because large-scale clearing of forests in the 1800's for agriculture had created abnormally high numbers of milkweed. Natural regrowth after fields were no longer farmed reduced the habitat acreage.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature declared in 2023 that the monarch was just "vulnerable" to extinction, rather than endangered. The population decline was not projected to continue, since the monarch population had stabilized around 2014 at about 55 million individuals.3

Recovery of the monarch is facilitated by people planting native species of milkweed, particularly common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca). The caterpillars in the Spring and Summer depend upon milkweed as their food source. Other species, such as the Milkweed Tussock Moth or Milkweed Tiger Moth (Euchaetes egle), also feed on milkweeds and absorb cardiac glycosides from the plant's milky sap.

both monarch and Milkweed Tussock Moth caterpillars absorb the toxic sap from milkweed plants

plants in the milkweed family, such as Asclepias syriaca, provide toxins to monarch butterflies that protect the adults from predation

In the Fall, adult monarchs migrate through Virginia and from Virginia to the Gulf Coast before flying to Mexico. Migration occurs only in daylight. At night, the monarchs gather at "roosts" or "bivouacs" in trees. In the morning, after body temperatures rise to 55°F, the monarchs resume their journey south. Migration south requires starting in September or October, so on the trip the mornings will heat up soon enough to allow for a full day of flying.

Monarchs born at the end of summer can migrate 3,000 miles to Mexico. That generation lives as long as eight months. The butterflies who overwinter in Mexico make a return migration to lay eggs and start a new generation in the southwest of the United States, before finally dying.

Not all monarchs try to fly to Mexico. Some near the Georgia-Florida border may choose to spend the winter in South Florida roosts, while other go to pine, cypress, and eucalyptus trees on the California coast.4

adult monarchs that overwinter in Mexico feed on nectar and pollen

There is no guarantee that the migration will continue. On the West Coast, millions of monarchs living west of the Rocky Mountains used to migrate to overwinter in California at about 400 different sites. Voters approved a bond issue in 1988 to acquire the roosting sites. The California Department of Parks and Recreation, other government landowners, private corporations, and individuals sought to protect the overwintering trees from harvest, in contrast to illegal logging in Mexico's overwintering forests.

Excessive tree trimming, new development, and wildfires have damaged or destroyed sites and reduced their capacity to harbor adult butterflies. Drought has killed patches of non-native blue gum eucalyptus which had neared the end of their lifespan, but have protected monarchs for the last century. Pesticides in milkweed and plants used for nectar feeding have affected population numbers, and warming temperatures may have enticed some monarchs to become year-round residents rather than migrate south to warmer winter roosting sites.

In 2018 and 2019 the overwintering populations in California had dropped to 30,000 monarchs, with the largest number concentrating at Pismo State Beach. Population models suggested the species was at a tipping point, and in 2020 the Xerxes Society estimated the total number of migrating monarchs in California at just 2,000. That was a decline of 99.9% from the 10 million monarch butterflies that once lived in the state.

Larger populations of non-migrating monarchs may exist in San Francisco and other areas where milkweed is surviving year-round. Those populations keep the species from disappearing on the West Coast. As one professor commented regarding the San Franciso monarchs:5

in the recent past, West Coast monarchs migrated and overwintered at multiple s

Source: Xerces Society, Western Monarch Count

The decline in the overwintering population may be offset by the natural increase in monarch populations during the summer. One female can lay as many as 500 eggs. A 2022 study reported that the summer population had been steady for the last 25 years, suggesting that efforts to expand the number of milkweed plants had not enhanced the natural recovery. According to one of the study's co-authors:6

monarch caterpillars spend time in a chrysalis to metamorphose into butterflies

The study's co-author was aware that populations had declined in the Midwestern breeding range, perhaps because of the herbicide glyphosate being used more widely in corn and soybean fields. In the northern part of that range, however, climate change had improved the habitat and summer breeding populations were increasing. The threat to the survival of the species was during from the southern migration and at the wintering sites, not an absence of milkweed during the summer.

The scientific conclusion is:7

The survey of colonies in 2023-24 revealed a 59% decline in the acreage covered by the overwintering insects compared to the previous year. The dry summer in 2023 lowered milkweed nectar availability during the summer. The hot, dry weather affected the autumn migration, resulting in the lowest number of monarchs in Mexico since the winter of 2013-14.8

Planting extra milkweed added another factor that disrupted the migration pattern. People interested in expanding the summer monarch population bought a non-native tropical milkweed, Asclepias curassavica, from garden stores. That milkweed reproduced and lived throughout the winters in southern Texas and along the Gulf Coast. Some monarchs adapted and established a year-round population, without migrating to Mexico for the winter.

As with the native milkweed species, the tropical milkweed is home to the protozoan parasite called OE (Ophryocystis elektroscirrha). Caterpillars ingest it along with the latex-rich juices of the milkweed plant, including the cardenolides that deter predation. Adult monarchs who start to emerge from their chrysalises carry spores of the parasite. The parasite prevents successful emergence of some adults, while those who do fly away and spread the parasite further are weakened and die prematurely.

tropical milkweed, Asclepias curassavica, survives over the winter and allows quick reinfection of migrating monarchs with a parasite

Source: Wikipedia, Asclepias

The migration cycle weeds out the sick monarchs, blocking transmission of the spores to the wintering grounds. The milkweeds are annual plants, so during the winter all of them - including the infected milkweeds - die. That interrupts the infection process. When new migrants head north, healthy monarchs encounter newly-grown milkweed plants which have not been infected yet by the parasite, and a healthy monarch population expands again.

Infection by the parasite explains why at the end of summer, the population of monarchs starting the migration south is stable but winter populations are so thin. Assessments of night roosts document that the population declines significantly during the migration. The protozoan parasite OE, not an absence of milkweed or the presence of pesticides, appears to be the greatest threat to the migrating monarch population.

The non-native milkweed that lives during the winter provides a year-round source of the debilitating parasite. The first generation of migrants flying north in the spring can become infected, threatening the health of the whole summer "crop" of monarchs. The Xerxes Society says:9

monarch caterpillars graze from the underside of leaves, providing some protection from hungry birds unfamiliar with their bad taste

The US Fish and Wildlife Service declared in 2020 that the monarch qualified for being listed as a endangered or threatened species. Further action was precluded, however, because the Federal agency had higher priorities and lacked the staff to complete the listing process.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature declared the migratory monarchs of North America to be an "endangered" species and added it to the Red List in 2021. The US Fish and Wildlife Service announced on December 10, 2024 that it was prepared to list the species as "threatened" under the Endangered Species Act:10

However, the Federal agency reopened the comment period and delayed a decision. Conservation efforts could impact a wide range of land use practices in the United States, due to the general habitat use and wide distribution of monarch butterflies. As described in an Oregon paper:11

Biologists calculated that the western population overwintering in California in January 2025 was less than 10,000 monarch butterflies. That was the second lowest total since counts started in 1997; in 2020, there were only 2,000 monarchs. In the 1980's the population was estimated at 4,000,000. The current number reflected a 95% decline in the western population, matched by an estimated 80% decline in the eastern population that overwintered in Mexico.12

The overwintering population of eastern migrating monarchs doubled in 2024-25 from 2.2 acres the previous winter to 4.42 acres. The key forested habitat in Mexico continued to shrink by roughly 10 acres per year, due primarily to illegal logging and drought.13

New technology developed by Cellular Tracking Technologies finally allowed scientists to apply a tiny, solar-powered sensor to the thorax of track individual butterflies. That offered a more effective technique that tagging butterflies with stickers, since only 1% of the tagged insects were recovered.

As butterflies with sensors migrated south to Mexico, their location was recorded when they passed within 300 feet of a Bluetooth-enabled Motus telemetry tower. The Motus network is a key scientific tool used to track many different species.

A monarch tagged at Harrisonburg, Virginia on September 23, 2025 and arrived at the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve on November 9. In a straight line, that 47-day flight would have been over 1,800 miles.

new sensors allowed tracking of individual monarchs migrating in Fall 2025

Source: Birds Canada, Tracking Monarch Butterflies from Long Point to Mexico with New Motus Technology (November 28, 2025)

The actual distance was longer. The butterfly migrated south to Alabama, turned west to reach Arkansas, flew along the Oklahoma-Texas border, and then turned south to Mexico. The butterfly, "JMU 004," flapped its wings and caught air currents which allowed it to go 40-50 miles per day.

Navigation was accomplished by using two compasses. The sun was the guide on clear days while ultraviolet light was used on cloudy days. The latest calculation was that only 25% of the monarchs that started towards Mexico successfully completed the journey. The swensors were expected to document if some monarchs flew south to Florida and Cuba, then westward across the Gulf of Mexico.14

Source: Monarch Joint Venture, June 2025 MJV Webinar: The Science of Radio Tagging Monarchs

population trends of monarch butterflies can be measured by the acreage where they overwinter in Mexico

Source: World Wildlife Fund, Eastern monarch butterfly population nearly doubles in 2025 (March 6, 2025)

monarch caterpillar feeding on milkweed

monarchs feed on milkweed as caterpillars, and on the nectar/pollen as adults

Source: National Park Service, Monarch Butterfly on Milkweed Plant

most monarchs overwinter in just a few patches of Mexican forest