peregrine falcons scrape nests into gravel on cliffs and raise juveniles in mountainous areas

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), Peregrine falcon protecting chicks

peregrine falcons scrape nests into gravel on cliffs and raise juveniles in mountainous areas

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), Peregrine falcon protecting chicks

Falcons are fast-flying predators, reaching 200mph while diving on smaller birds that will become a meal. Two species nest in Virginia, the peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) and the American kestrel (Falco sparverius).1

When European colonists arrived, peregrine falcons were concentrated in the Blue Ridge and mountains in Appalachia. Ridges provided topographic relief and updrafts for flights from the nest to hunt other birds. Nests were typically scraped into a patch of gravel on a cliff ledge.

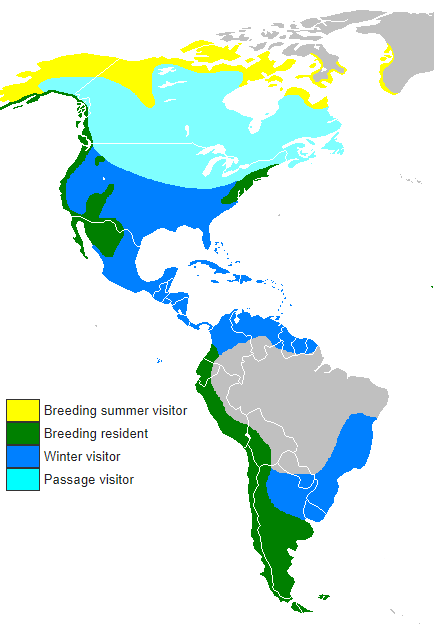

The resident population was low, with an estimate of just 350-500 breeding pairs in the eastern United States before World War II and double that number in the western states. In addition, peregrines migrating each year from Alaska, Canada, and Greenland to Central and South America would fly along the Atlantic Ocean coastline, visiting barrier islands on Virginia's Eastern Shore during the journey.

peregrine falcons are a resident species in Virginia, and also migrate through along the barrier islands

Source: Wikipedia, Peregrine Range Map

The population dropped dramatically after World War II. There was no nesting occurring at 133 historic eyries east of the Mississippi River in 1964, including the 24 eyries which had been identified in Virginia's Appalachian Mountains.

Using the authority of the Endangered Species Conservation Act of 1969 (predecessor of the 1973 Threatened and Endangered Species Act), the US Fish and Wildlife Service listed the species as "endangered" in 1970.

peregrine falcons have extraordinary vision to spot prey

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), Peregrine Falcon (by Craig Koppie)

Though some habitat had been disturbed, the main cause was an unexpected impact from the pesticide DDT and other chlorinated hydrocarbons:2

peregrine falcons can lay four eggs in the nest

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, But Four Makes it a Party! (March 30, 2022)

After use of DDT was banned in 1972 in the United States, the Eastern Peregrine Falcon Recovery Team and other recovery teams raised falcons in captivity and released 6,000 back into the wild. The habitat had remained suitable, and the restocking was successful. Starting in 1974, young falcon chicks were brought from the breeding facility at Cornell University to suitable release locations:3

in 2021, a pair of peregrine falcons in Richmond raised four chicks in the nest

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Keeping Up With The Peregrines

Hacking captive-bred peregrine chicks was done first in the Coastal Plain. There was suitable nesting habitat in the Blue Ridge and other mountains in western Virginia, but predation there by great horned owls was a higher risk.

Peregrine chicks were transferred to towers on barrier islands between 1978-1985, plus the roof of a nine-story building in Norfolk. Of the 115 birds released from eight sites near the Atlantic Ocean, 85% of those which fledged managed to successfully disperse to new territories. Challenges included protecting the chicks from predation by great horned owls

There were 24 known peregrine nest sites in the Blue Ridge when the recovery effort began, and none were being used when hacking efforts started in 1985. Far more sites were available as well. A 1992 helicopter survey of the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests and Shenandoah National Park mapped 100 sites which were suitable for nesting.

In western Virginia, 131 peregrines were released from nine sites between 1985-1993. Sites were located on Mt. Rogers, Clinch Mountain, in the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests, in Shenandoah National Park, and even in downtown Roanoke in 1992 and 1993. The program was successful, with 90% of the chicks dispersing to new territory.

The genetics of the reintroduced peregrines are different from the original Appalachian peregrines, a variant of the Falco peregrinus anutum subspecies. Those genes were lost as the population crashed, so:4

In 1982, a pair of peregrines finally nested again in Virginia. By 1998, there were 17 nesting pairs in Virginia, and 1,650 in the United States. Five years later, there were over 2,000 nesting pairs across the United States. Eggshell thinning diminished, even though use of chlorinated hydrocarbons has continued in Central and South America and DDE (a byproduct of DDT) is still present throughout Virginia.

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Falcon Banding 2024: Protecting and Monitoring Virginia's Peregrine Falcons

The Federal recovery program for regular release of captive birds has been completed, and the species was delisted by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in 1999.5

Though the Federal government removed the falcon from the list of threatened and endangered species, it is still considered a species of concern in several states. In North Carolina, popular mountain climbing routes are closed when falcons are nesting nearby. In Virginia, the species is still listed as "threatened" by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources.

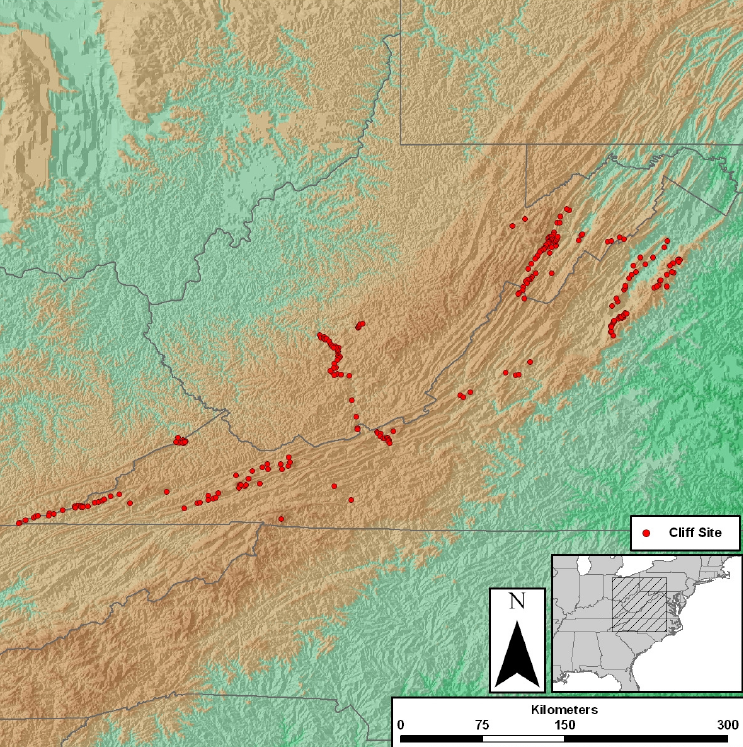

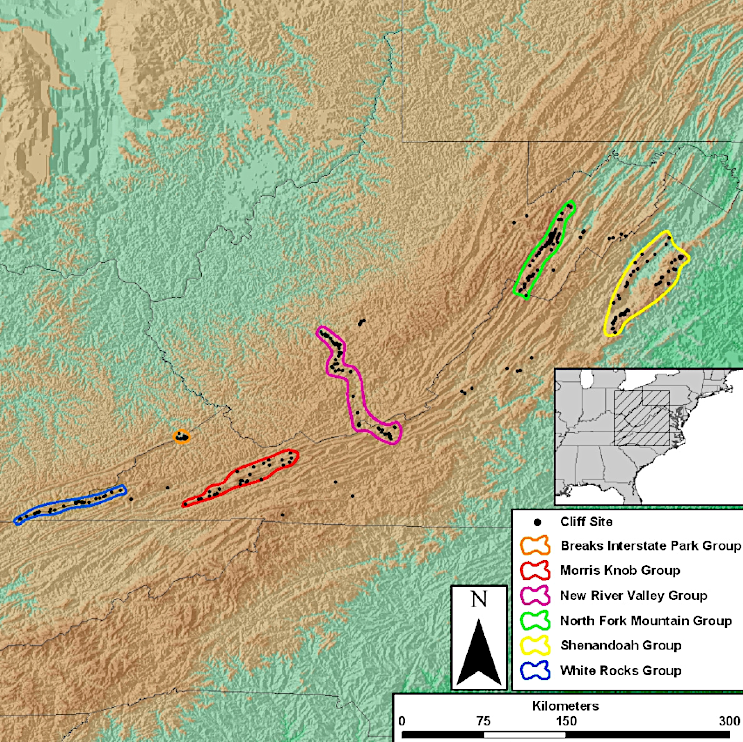

The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources restarted "hacking" chicks in the mountains in 2000 in hopes of establishing a nesting population in the western part of the state. There were no natural nests on the exposed cliff faces where vegetation was not a barrier to nesting, perhaps in part because of disturbance by hikers and mountain climbers. A 2006 survey identified six areas that were most suitable for re-introduction with hopes that fledged falcons would return to establish natural nests.

six areas were identified as most suitable for reintroduction, from the many cliff faces mapped in Virginia/West Virginia in 2006

Source: College of William and Mary, An Investigation of Cliffs and Cliffnesting Birds in the Southern Appalachians With an Emphasis on the Peregrine Falcon (Figure 6, Figure 7)

The state agency monitors the breeding success at falcon nests, and even has a "falcon cam" trained on a ledge of a window of a tall building in Richmond where falcons regularly raise a brood. Biologists transferred chicks primarily from nests constructed on high bridges in Tidewater, where the mortality rate was high. Many were falling into the river or being hit by vehicles crossing the bridge, but transplanting the chicks to hacking sites in the mountains increased their survival potential:6

peregrine falcons nest almost annually on a ledge of the Riverfront Plaza building in Richmond

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries Richmond Falcon Cam, First Egg Laid!

A pair of peregrines raised young regularly on the smokestack of the Possum Point Power Station in Prince William County, using a nest box constructed thee by research biologists. Each year, biologists would climb 350 up the tower and bring the young chicks ("eyases") to the ground, where their health was evaluated and bands were placed around the leg. Spotting those birds later helped to monitor dispersal and reestablishment of the population, with some found later in Boston and New York.

One year, two of the chicks were successfully banded and returned to the nest, but a third escaped. When captured two days later, it was transferred to a hacking site in Shenandoah National Park.7

In 2015, chick 24/AU hatched in 2015 at a nest box on the Possum Point Power Station smokestack. It was a male that established a territory in Richmond four years later. In 2020, with its mate, it starred in the Falcon cam trained on the nest on a ledge at Riverfront Plaza. The two produced four eggs an fledged one chick that year. In 2021, before the start of the mating season, the male flew into a wire or vehicle. The injured bird was examined by Richmond Animal Care and Control, and was euthanized because damage to its wing was too great for recovery.8

in 2020, the female peregrine falcon laid four eggs at her nest on the Riverfront Plaza building in Richmond

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries Richmond Falcon Cam, Fourth Egg

peregrine falcon viewing downtown in Richmond in 2020

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries Richmond Falcon Cam, Courtship at the Box

Peregrine falcons compete for mates. In 2021, a female from New Jersey killed the female who had been nesting in Virginia Beach with the same male partner for five years. The male then mated with the new partner, nesting on the 20-story Town Center. From the three eggs laid, one chick survived.

Peregrines have nested on tall buildings in Richmond, Virginia Beach, and Reston plus the Berkeley Bridge in Norfolk, the George P. Coleman Memorial Bridge between Yorktown-Gloucester Point, and the James River Bridge.9

By 2023, after 6,000 captive-bred peregrine falcons had been reintroduced to the wild across 34 states, there were 50 breeding pairs in Maryland and Virginia. That year the peregrines nesting on the cliffs of Maryland Heights, across the Potomac River from Harpers Ferry, successfully raised three chicks.

Source: Wildlife Center of Virginia, What Hawks and Falcons Have in Common as the Sky's Top Predators

peregrine falcons are nesting and successfully raising chicks on the cliffs at Harpers Ferry

Source: National Park Service, Peregrine Falcons at Harpers Ferry

young peregrine falcon

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), Peregrine Falcon, juvenile

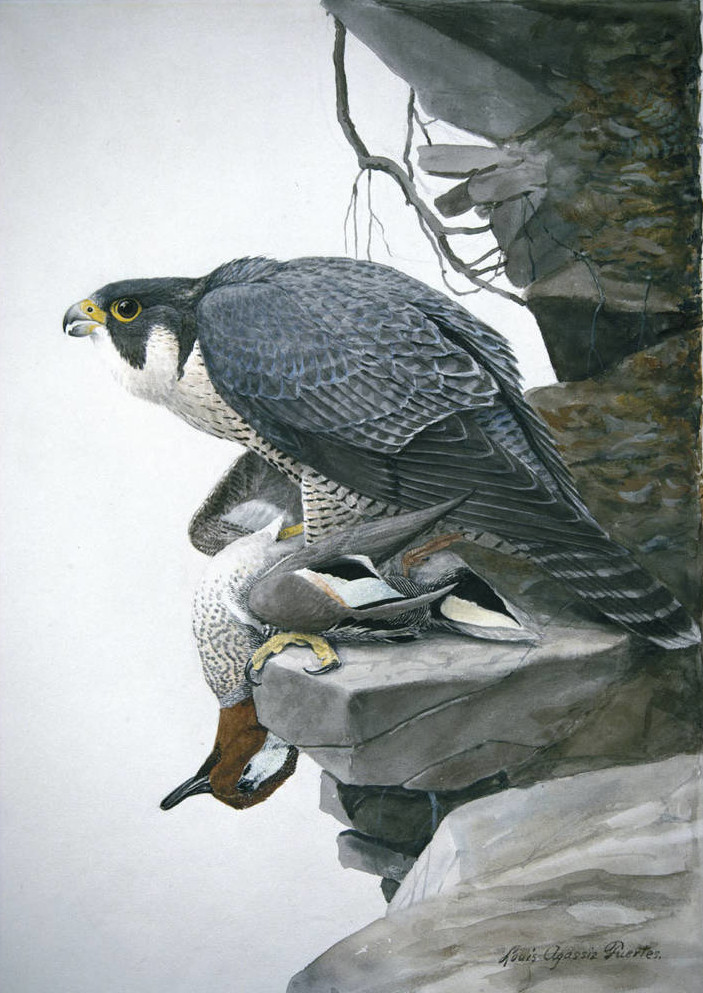

falcons are predators who dive at fast speeds to kill other birds

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), Peregrine Falcon (painting by Louis Agassiz Fuertes)