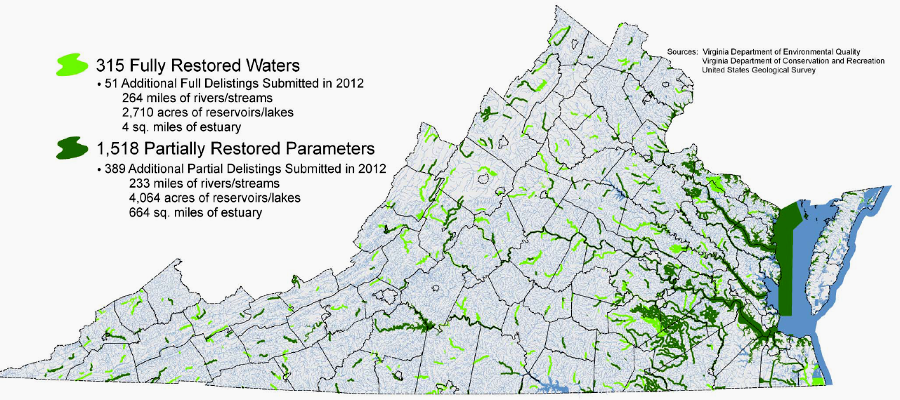

waterbodies delisted from 303(d) "dirty water" list by February 2012, showing that water quality can improve in Virginia

Source: Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), 2012 Draft Water Quality Assessment and Impaired Waters Integrated Report

waterbodies delisted from 303(d) "dirty water" list by February 2012, showing that water quality can improve in Virginia

Source: Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), 2012 Draft Water Quality Assessment and Impaired Waters Integrated Report

The question is not "Will the Environment of Virginia Change?" The only question is how; the environment is not static. For example, the globe has been warming and sea level rising for 18,000 years, dramatically transforming the Atlantic Ocean shoreline and creating the Chesapeake Bay. Humans have been adapting to environmental change ever since the first people arrived long before the formation of the Chesapeake Bay.

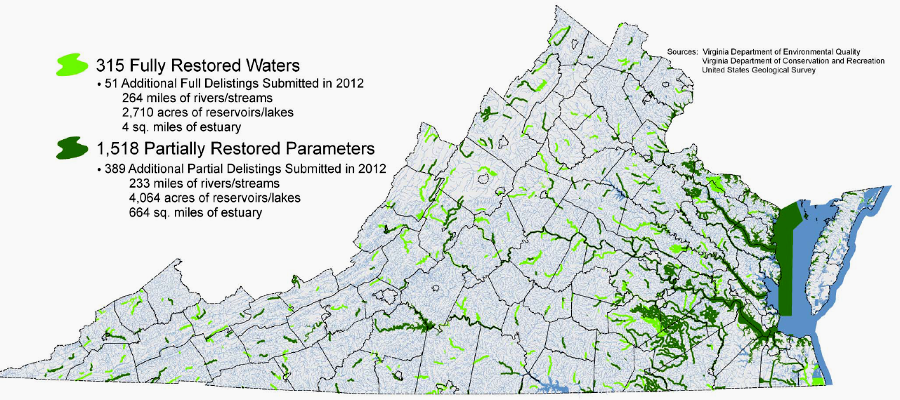

Native Americans arrived before the climate changed and deciduous forests emerged, and utilized whatever was available for food, tools, and shelter

Source: Virginia Humanities, Virginia Indian Archive, Polished Turtle Shell Cup or Bowl

Over the next few centuries, it is a sure bet that the ecosystems, habitats, and species in Virginia will continue to adjust to the impacts of changes in climate, evolutionary shifts, the arrival of invasive species, and the extirpation (local elimination) or extinction (complete, world-wide elimination) of species that can not adapt fast enough.

In some ways, environmental restoration will succeed. The chestnut tree may be restored to Appalachian forests, though hemlocks and ash trees may disappear. Streams/lakes/estuaries that do not meet Clean Water Act standards may be cleaned up (especially those impaired by just bacteria). At the same time, the less-visible coldwater corals growing on the edge of the Outer Continental Shelf may be seriously affected by ocean acidification.

hard and soft hexacorals grow in the deep abyss of the Baltimore Canyon

Source: Deep-water Mid-Atlantic Canyons, Coral Growth and Old Water

We will see rapid alterations due to continued human impacts as the population grows, and through gradual environmental impacts as sea level rises. If we look closely, we may also see some of the slow evolutionary shifts that occur naturally over time.

There's an ongoing debate over the role of the first humans in North America in the Pleistocene epoch, and whether their hunting pressure led to the elimination of the "megafauna" such as mastodons and giant sloths. Some of the more-dramatic shifts in the state that can clearly be defined as human-induced include:

Key moments that triggered public recognition of environmental problems included:

Threats to the natural and human environment from industrial facilities were addressed by air/water pollution controls imposed on point sources, starting in the 1970's. Smokestacks and pipes discharging waste are now regulated through Virginia Pollution Discharge Elimination System (VPDES) permits. The administration of those permits, delegated to the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), can vary as different governors define their priorities, but Federal laws establish minimum standards and the Environmental Protection Agency serves as a backstop to ensure compliance.

Today, non-point pollution is the toughest challenge to address. Sources of non-point pollution are diffuse. It is harder to assign blame and impose fees, and agricultural operations are largely exempted from the Clean Water Act. Virginia, in contrast to Maryland, seeks to minimize regulatory controls to meet conservation objectives, so Virginia focuses on incentivizing farmers to implement Best Management Practices such as nutrient management plans.

The inclusion of the Chesapeake Bay on the 303(d) list of "dirty waters" has resulted in a cleanup plan based on a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) study. That plan assumes specific actions will be completed by 2025, and "restoration" of the bay may be completed by 2040. Gradual improvement is predicted, but the end result will not be a Chesapeake Bay comparable to what John Smith saw in his 1608 journeys.

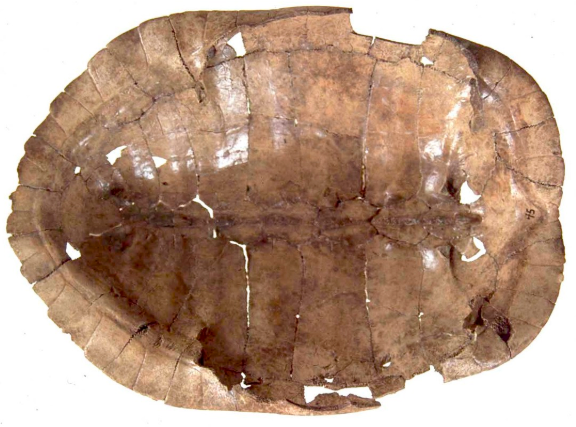

The old growth forests of Virginia that the first English colonists observed are gone forever. Some parks may ban logging forever, but it will take several more centuries before the return of even isolated patches of old growth. The Atlantic white cedar and cypress forests in southeastern Virginia swamps are now rare, and planted loblolly pine plantations dominate the managed forests on the Coastal Plain now. Black bears have managed to survive both east and west of the Blue Ridge, throughout the changes.

As the human population increases, it will be increasingly difficult to maintain large patches of undisturbed forest. Roads, power lines, and clearings for rural houses will increase, inviting edge-loving species like deer to expand populations even further. Coyotes will also take advantage of the altered habitats. One former native species (elk) has already been re-introduced to utilize the unnatural grasslands created by coal mining in southwestern Virginia.

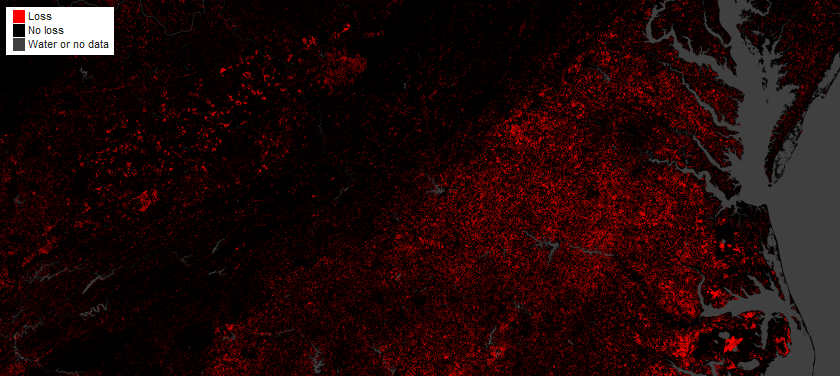

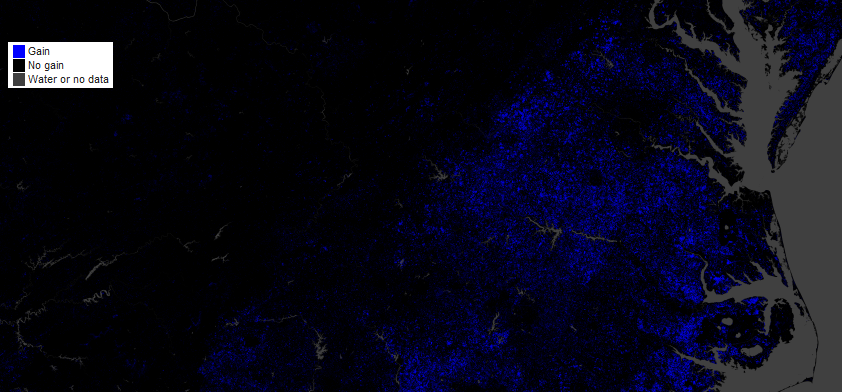

change in tree cover between 2000-2012 shows newly-forested areas, as well as area where trees were removed

Source: University of Maryland, Global Forest Change

loss of forests between 2000-2012 was greater east of the Blue Ridge, and less in the Valley and Ridge province

Source: University of Maryland, Global Forest Change

increase of tree cover between 2000-2012 was also greater east of the Blue Ridge

Source: University of Maryland, Global Forest Change