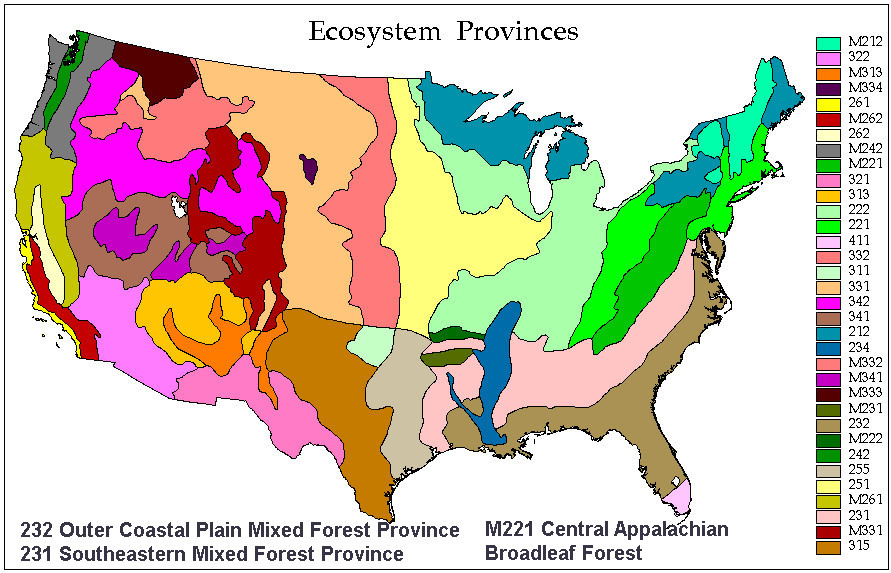

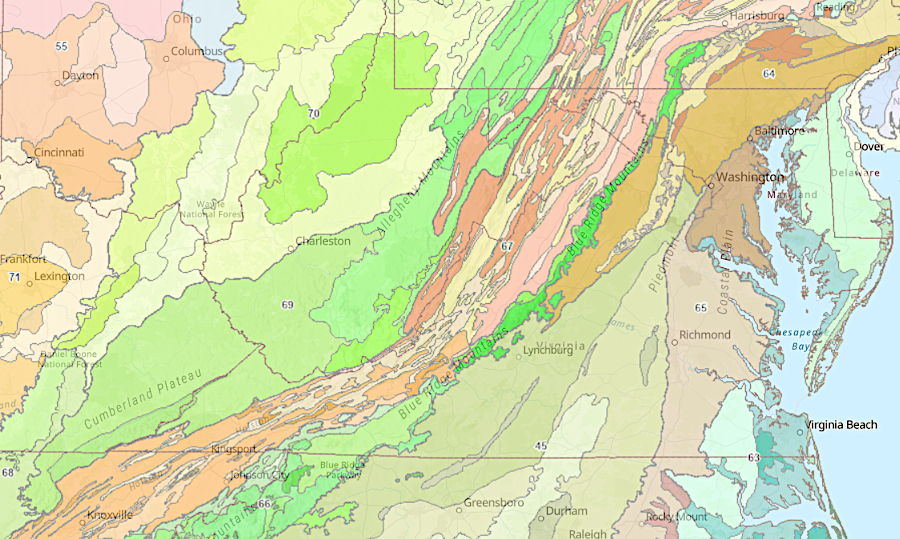

ecoregion boundaries are used in analysis of Land Use Land Cover (LULC) trends

Source: US Geological Survey, Land Cover Trends Project

ecoregion boundaries are used in analysis of Land Use Land Cover (LULC) trends

Source: US Geological Survey, Land Cover Trends Project

There are multiple ways to classify the patterns of vegtation and animal life on the earth. There are clearly differences between the ocean and the land, but within the ocean it is a judgement call on where to daw a line between shallow and deeep water ecosystems, or salt and freshwater ecosystems.

On land, most efforts to classify different terrestrial systems are based upon the differences in vegetation.

As defined by the Commission for Environmental Cooperation, Virginia is part of the Eastern Temperate Forest. Unless the land is disturbed, the climate and soils allow a dense forest to form with 100' tall broadleaf deciduous trees and needle-leafed conifers.1

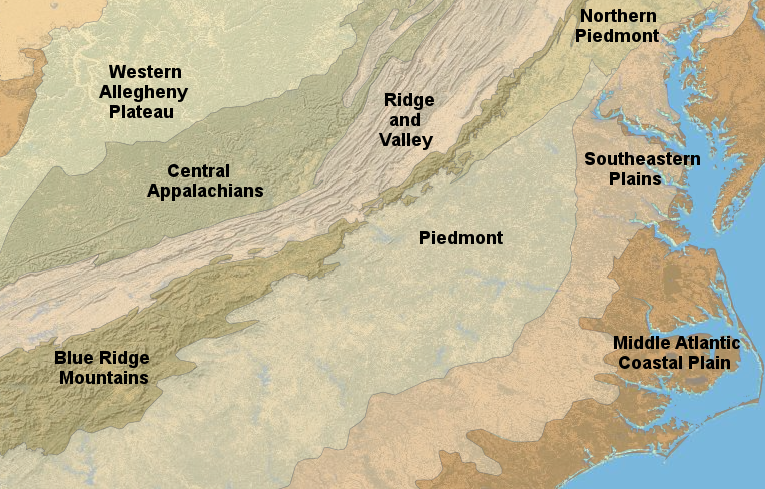

Virginia's ecoregions, as defined in the Commission for Environmental Cooperation's North American Terrestrial Ecoregions (2021)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

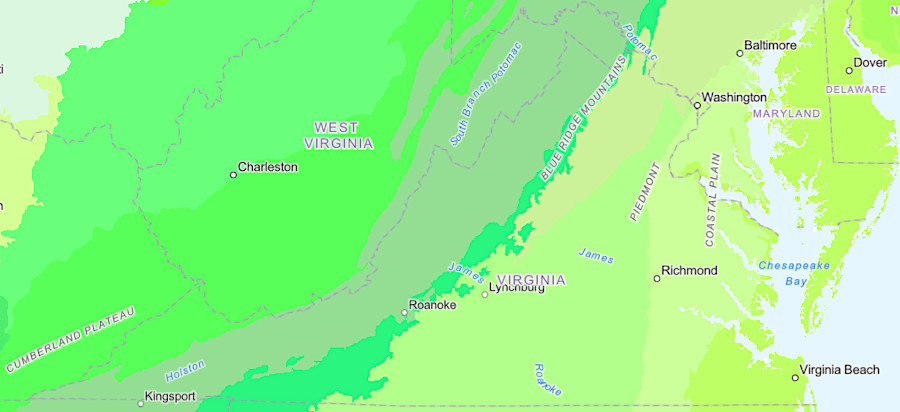

In Bailey's definition of ecoregions, Virginia includes the Outer Coastal Plain Mixed Province, Southern Mixed Forest Province, and the Central Appalachian Broadleaf Forest-Coniferous Forest-Meadow Province.2

Virginia includes three provinces within the ecoregions defined by Robert Bailey in 1995

Source: US Forest Service, Description of the Ecoregions of the United States

The Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation has a Division of Natural Heritage which categorizes the state's biological diversity. As required by Virginia Natural Area Preserves Act of 1989, the state agency has inventoried the places which have rare, threatened, and endangered plant and animal species; exemplary natural communities, habitats, and ecosystems; and other natural features of special value. Modified landscapes such as agricultural orchards and croplands, ecologically-barren ornamental gardens, and suburban yards with turf grass are not treated as "natural communities."

The Division of Natural Heritage classification hierarchy uses four levels to categorize the natural landscape:

- System

- Ecological Class

- Ecological Community Group

- Community Type

"Low-Elevation Dry and Dry-Mesic Forests" is one of the 14 Ecological classes defined by the Virginia Natural Heritage Program

Th 14 Ecological classes group together physiographically and topographically related community groups, which often co-occur on the landscape.

At the lower level, there are 82 Ecological Groups and 308 more-detailed Community Types. The definitions help distinguish the different biological resources across Virginia. An average person can distingish "forest" from "field" or "lake," but walking through an area and identifying boundaries where Community Types are different requires technical skills in plant identification, soil science, hydrology and geology.

Those skills alllow the biologists and other specialists working for the Natural Heritage Program, US Geological Survey, The Nature Conservancy, and other groups to identify which Community Types are common and which are at risk of disappearing as human development creates a "built environment" and transforms the landscape with roads, houses, and other infrastructure. Priorities for land conservation can then be based on the potential for Community Types and particular species to disappear.

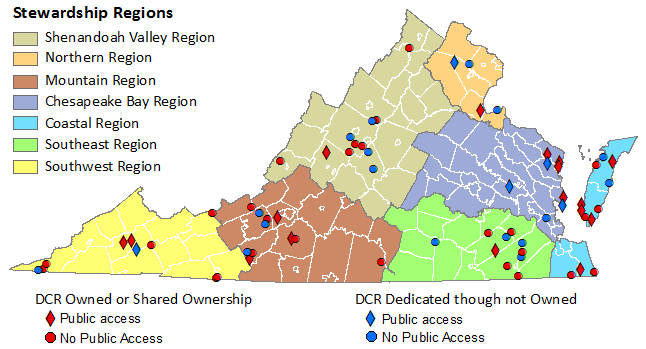

Techniques to maintain the diversity of Community Types include purchase of conservation easements, buying property rights to limit development and maintain existing natural areas. State and Federal agencies and non-government organizations acquire parcels of particular value. Most are opened to public use, but if disturbance would damage the natural resoures then some areas remain closed to all but researchers. Public use may also be limited at sites where the state acquired a conservtion easement but the landowner did not sell the right for the general public to visit.3

some Natural Area Preserves remain closed to public use to preserve sensitive resources, or because conservation easements were acquired without the right for public access

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Virginia Natural Area Preserves

The boundaries between ecosystems and habitats are not fixed. The changing climate is altering environmental conditions such as peak summer temperatures, dates of first/last frost, and amount of rainfall. Tree species adapted to old conditions may not be able to grow seedlings in a warmer, wetter climate with more intense storms. The firs now growing at high elevations may become "zombie forests," where mature trees are unable to replace themselves. In 50-100 years, as aging fir trees die off, a new forest composed of different specis may appear at high elevations.4

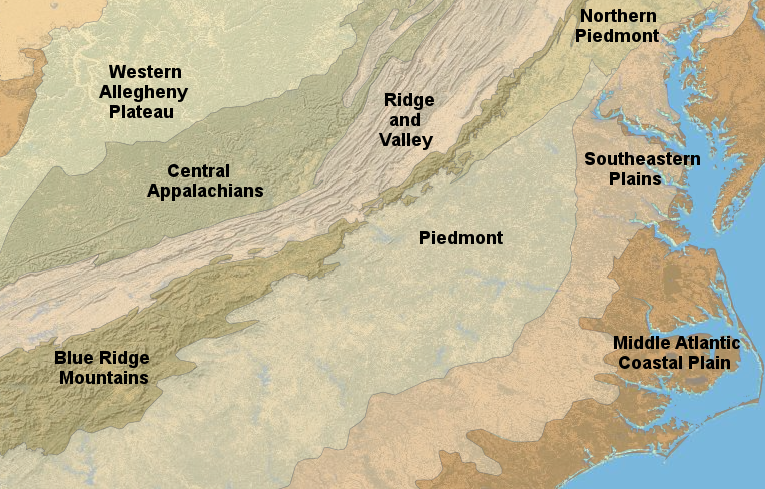

Virginia ecoregions, as classified by the Environmental Protection Agency (Omernik)

Source: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), EnviroAtlas

Prince William Forest Park protects remaining forested habitat in Prince William County, where development of housing (pink) has transformed the landscape

Source: The Nature Conservancy, Northeast Habitat Map