blue crabs are an iconic symbol of the Chesapeake Bay

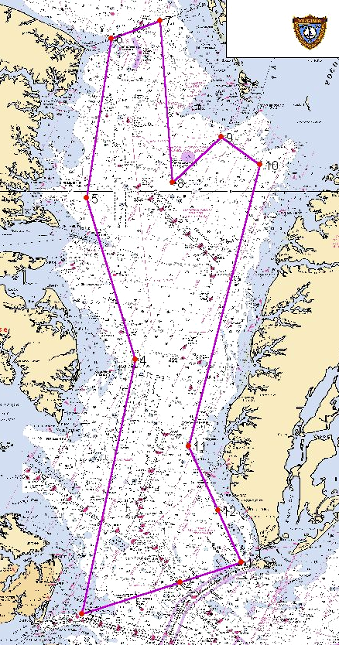

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Habitat Conservation

blue crabs are an iconic symbol of the Chesapeake Bay

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Habitat Conservation

The scientific name of the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus, means "beautiful swimmer - savory." Two of its 10 legs are modified into swimming paddles, and another two are pinchers desired for defense and grabbing food.

The name indicates why managing this particular species is so important to those trying to restore the Chesapeake Bay. Economically, the blue crab harvest has provided the highest value of any Chesapeake commercial fishery, but after a record harvest in 1993 the population declined substantially.1

The blue crab is a keystone species, fundamental to the ecology of the bay. Striped bass and other fish depend upon blue crabs as a key part of their diet, while crab larvae provide food for various filter feeders such as menhaden and oysters.

The population decline was caused by two factors: over-harvest and reduction of suitable habitat.

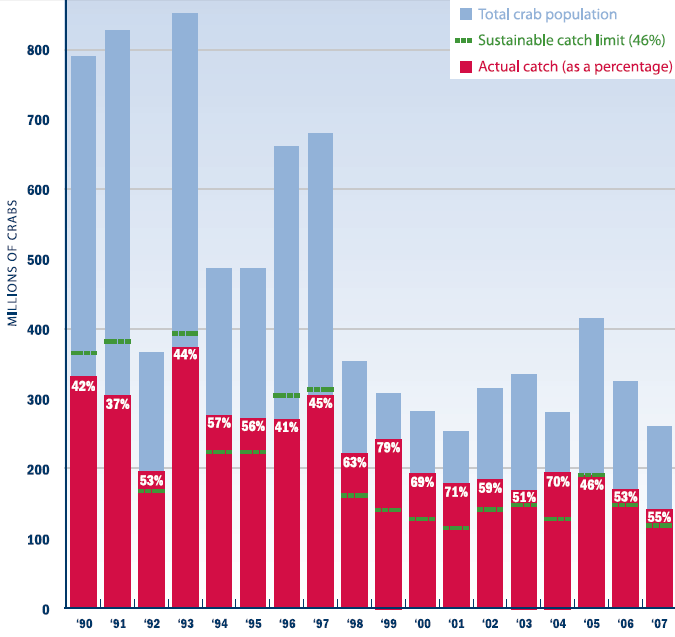

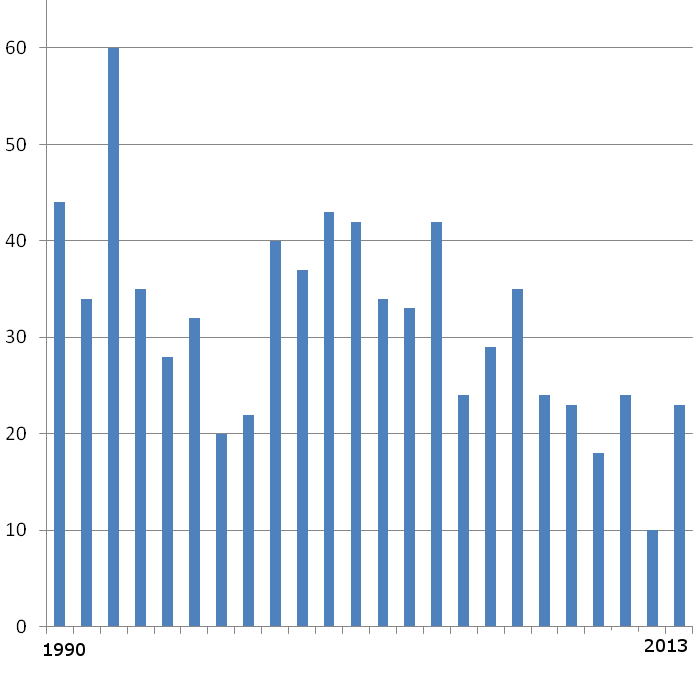

Scientific research indicates that 46% of the total crab population could be caught annually, but the harvest exceeded that sustainable level. In 1948, there were 60,000 crab pots in the Chesapeake Bay, but that number expanded over the next 50 years to a million. In 2007 the population crashed, and in 2008 Maryland and Virginia cut the harvest by 1/3. In the prior 10 years, the harvest level had averaged 62% of the population, far beyond sustainable levels.2

The Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) habitat of the blue crab declined by 50% after 1960, as sediment blocked light from penetrating the water in the Chesapeake Bay. Oyster dredging and other fishing practices scalped the bottom of the bay, physically ripping up the SAV beds in the same way an all-terrain vehicle can convert a productive pasture to into a mud bog.3

Overharvest and habitat destruction by crabbers are not the only causes of population decline. Sediment damaging the habitat of the blue crab comes from places far upstream, including the Giles County (headwaters of the James River near the West Virginia border) and Augusta County (headwaters of the Shenandoah River near Staunton). Highlighting the tasty blue crab - No crab should die suffocating in oxygen depleted water. It should be steamed and eaten with Old Bay and melted butter - helped build support for water quality controls that will help "Save the Bay" in places far from the bay itself.

advertising to create support for stream buffers in the Shenandoah Valley emphasized a key benefit of the Chesapeake Bay for people who live far away from the shoreline

Source: Chesapeake Club and Friends of the Rappahannock

The decline of crab harvests from the high of 113 million pounds in 1993, to a low of 49 million pounds in 2000, led to a parallel decline in jobs. Crab-related employment declined 40% between 1998-2006, though bay-area processing houses imported crabs from Louisiana as an alternative supply source. In 2008, the U.S. Secretary of Commerce declared an economic disaster, providing some funding to mitigate the impacts on the local watermen and processors.

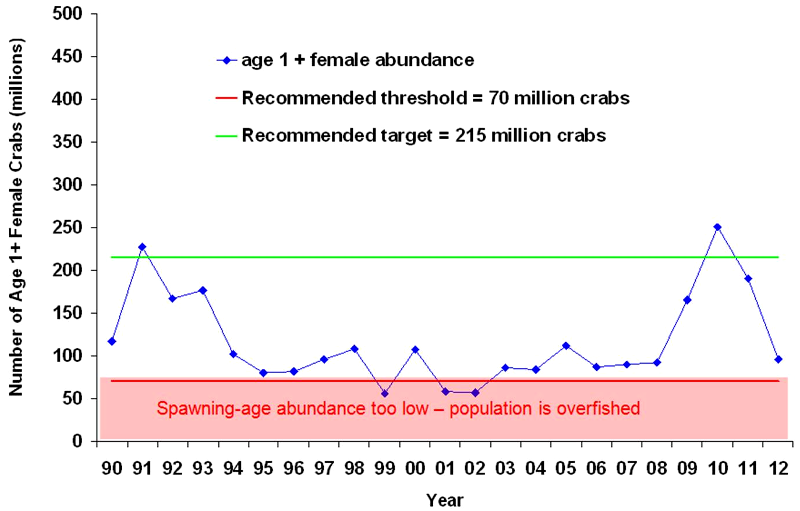

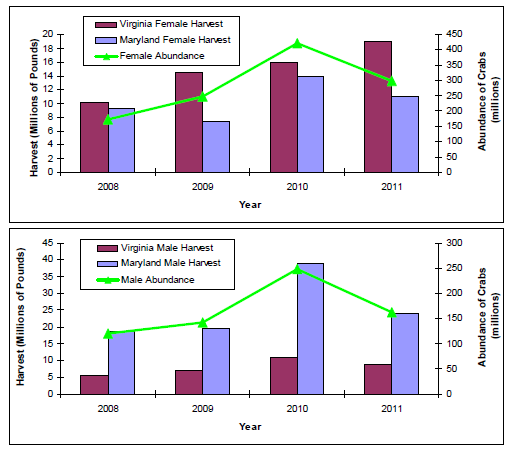

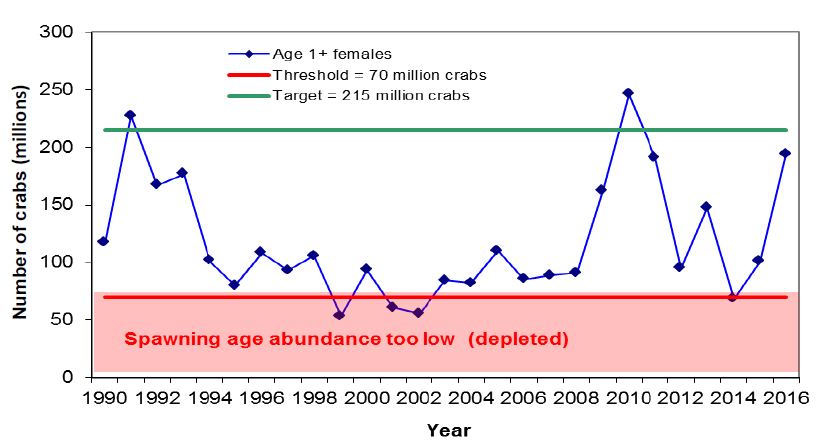

Scientists have used different measures of sustainability. After the 2007 population crash, the old measure (46% of the total crab population) was replaced with a new sex-specific measure: protect 70 million adult female crabs over the winter as a minimum, with a target population of 215 million spawning-age female crabs.

In 2012, the Chesapeake Bay Program Sustainable Fisheries Goal Implementation Team defined a minimum "exploitation level" at 25% of the estimated female abundance, and a threshold for overharvest was set at 34% of that population. Those thresholds are tied to commercial harvest, and do not include the harder-to-measure recreational crab harvest (which was estimated to be 7% of the total in 2010).4

between 1990-2007, blue crab harvest levels exceeded the 46% sustainable level in 12 of the 18 years, leading to a ban on harvest in 2008

Source: Chesapeake Bay Foundation, "Bad Water and the Decline of Blue Crabs in the Chesapeake Bay," Chesapeake Region Blue Crab Catch As Percentage Of Total Population (Figure 4)

A winter dredge survey that started in 1988 now collects 1,500 samples throughout the bay annually. Reports from that survey generate news stories about the health of the population, which can vary within 12 months from "Blue crab population rebounds" to "Blue crab population at record low."

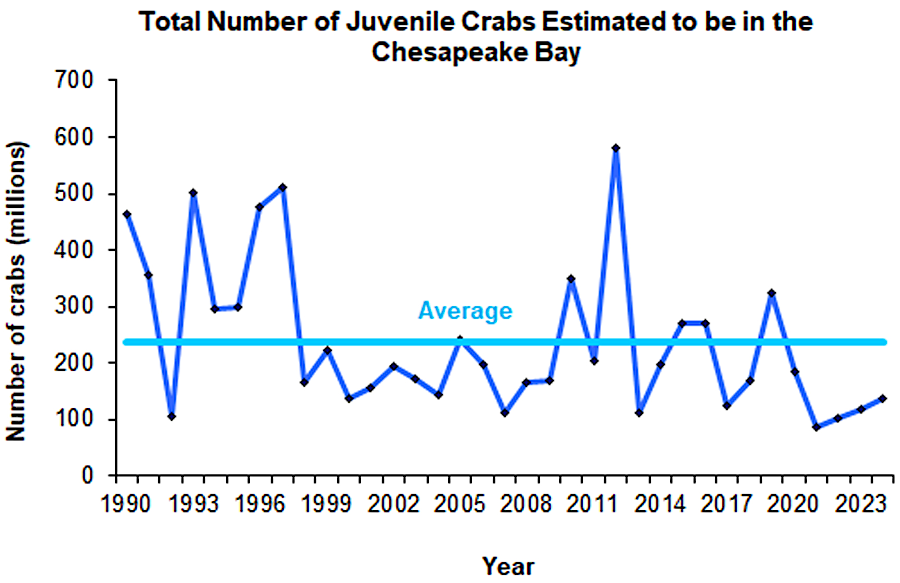

Females collected in the survey that are bigger than 2.4 inches are considered large enough to spawn in the following year. The ratio of all crabs larger than 2.4 inches (harvestable stock) to the smaller young-of-the-year crabs helps to determine the status of the population; an increase in juvenile crab abundance suggests the population is growing.5

the minimum benchmark for defining "sustainable" harvest and the target benchmark have changed over the years, but population management requires protecting blue crabs from over-harvest (plus conservation of habitat)

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Blue Crabs

Blue crabs migrate. Over their life cycle (up to 3-4 years), blue crabs of the Chesapeake Bay will occupy different habitats in the estuary and open ocean.

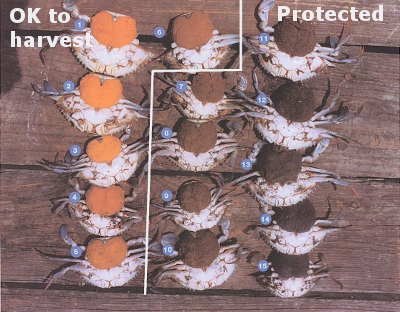

A maturing female (sook) sheds her shell for the last time between May-October. For about two weeks before her new shell hardens, she can mate with multiple males (jimmies). That is her only window for mating. The following Spring, she retrieves sperm she has stored since mating to fertilize each batch of eggs. If she is one of the lucky 15% who survive for a second year of reproduction, she still relies upon that brief period of mating to fertilize the 750,000-8,000,000 eggs she places in an orange "sponge."6

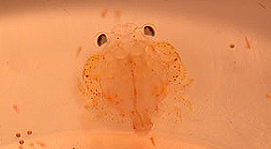

spawning female crabs (sooks) carry their eggs in an external mass (sponge) for two weeks, before the eggs hatch into larvae (zoea) that develop into megalopae and then juvenile crabs

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Blue Crab Online Resource - Life Cycle

After the fertilized eggs are carried by a mature female for two weeks, the larvae that first emerge will seek out high-saline waters (at least 26 parts per thousand) and drift out of the Chesapeake Bay to feed on plankton in the Atlantic Ocean. The growing larvae go through seven (occasionally eight) molts while circling over the Continental Shelf.

The last form called megalopae will move up and down in the water column to find the currents necessary to drift back into the Chesapeake Bay and then move upstream towards less-saline waters. As the megalopae develop into a juvenile crab and mature in seagrass beds and marshes, they shift their food preferences from macroinvertebrates to oysters and hard clams.

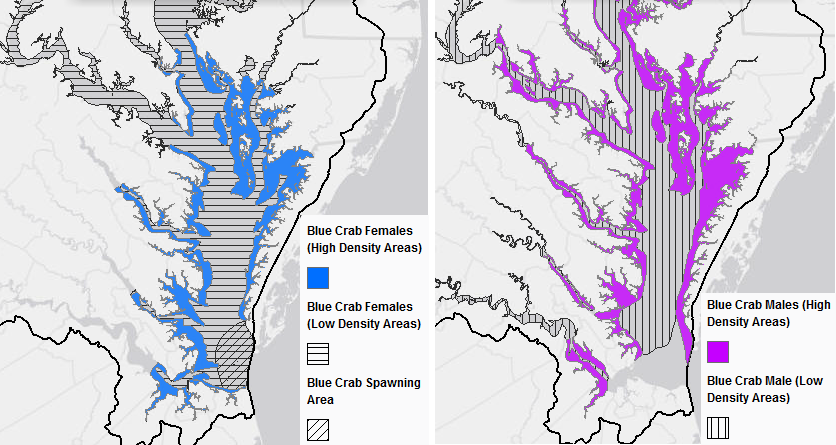

in the summer, male crabs are far more common than female crabs in the Potomac River up to King George County

Source: ChesapeakeStat, Make Your Own Map

Blue crabs are willing to scavenge multiple types of food, and even cannibalize other blue crabs. That is one reason state officials have not chosen to raise crabs in hatcheries to restock the population when it fluctuates to low points - though the primary reason is that the productivity potential of the wild population is sufficiently high to restock the bay, if pregnant female crabs are protected long enough so they can spawn and release millions of eggs from each "sponge."

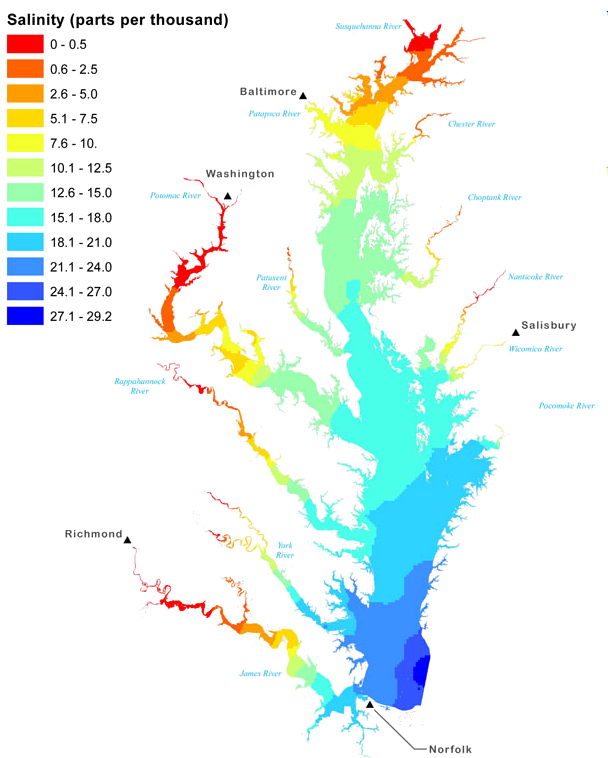

Males and females have different habitat preferences; males are willing to travel further up the tributary rivers and live in lower-saline waters. Males prefer salinity of 3-15 parts/thousand, while females stay in areas with at least 10 parts/thousand. Because the upper Chesapeake Bay (the Maryland portion of the bay) is less saline than the mouth, watermen in Maryland harvest more male crabs than in Virginia.

Because one male can fertilize multiple females, the sex ratio is unbalanced. In 2020, there were 39 million males to 158 million females, but biologists were confident that there was an adequate number of males to maintain the population.7

Until 1992, it was not clear if there were preferred areas where crabs would overwinter by burrowing into the muddy bottom of the bay, or if it was essential to protect the entire bay's bottom. It turned out that mature crabs preferred spending the winter in deep channels (so long as oxygen levels remain above 5mg/l), before emerging when water warms up in the spring.

Female crabs mate only once after their final molt, though they may mate with multiple male crabs at that moment. The pregnant females do not stay in the low-saline Maryland waters where they chose to mate. After mating, the females walk as much as 100-200 miles, primarily along the eastern edge of the deep channel in the bay, to the more-saline waters near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay in Virginia.

In 2015 Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe tweaked his counterpart in Maryland by proclaiming in a radio interview:8

A small number of blue crabs breed and "birth" larvae in the high-salinity coastal bays of Maryland along the Atlantic Ocean shoreline, so it is not correct to claim that absolutely 100% of blue crabs in Maryland come originally from Virginia. In the Chesapeake Bay, however, all the blue crabs are Virginia-born.

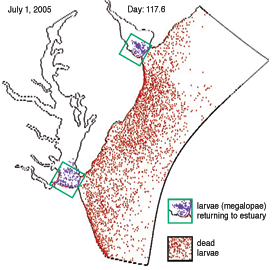

most blue crab larvae move to the Atlantic Ocean and die there; the variable return of megalopae (determined by ocean winds and currents) triggers fluctuations in populations of the Chesapeake and Delaware bays

Source: Chesapeake Quarterly, The Offshore Odyssey of Blue Crab Science (July 2012)

Mating occurs in Maryland's portion of the Chesapeake Bay, and the communication director for the governor of Maryland once noted "It's not just Virginia that's for lovers." The female blue crab retains the sperm packets separate from her eggs as she walks south on the bottom of the bay to the saltier waters in Virginia. The eggs are released and fertilized there. Some of the larvae ultimately float up the bay and grow into mature crabs that are harvested in Maryland, but a University of Maryland scientist confirmed the claim of the Virginia governor:9

female crabs in the Chesapeake Bay migrate south to overwinter where salinity reaches at least 26 parts per 1,000 - eggs are fertilized and released there, so even crabs harvested in the Maryland portion of the bay are native-born Virginians

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, Chesapeake Bay Mean Surface Salinity - Fall (1985-2006)

The realization that crab larvae mature initially in the Atlantic Ocean has explained some of the fluctuation in crab populations in the Chesapeake Bay. After World War II, the dominant scientific theory was that blue crab larvae stayed within the bay. In years when rains were heavy, the larvae would be washed into the ocean. Since the assumption was that larvae had no way to swim back into the Chesapeake Bay, they would die in the ocean and the blue crab population in the bay would decline the following year.

In the 1970's, scientists discovered that the larvae did spend 1-2 months in the Atlantic Ocean, and they had a mechanism to move back into the bay from the ocean. Fresh water currents on the surface of the bay flow in plumes out into the Atlantic Ocean, while salt water currents lower down in the water column flow from the ocean into the bay. Young larvae swim upwards, and flow out into the ocean on surface currents. As larvae mature into megalopae, they drop lower below the surface and catch a ride with a saltwater current back into the Chesapeake Bay.

Blue crab megalopae do not catch ride at random, just hoping the current will carry them towards the grass beds and shoreline marshes of the Chesapeake Bay. The megalopae use chemical clues to recognize where they are in the ocean, and when a current is headed inland rather than further out to sea.

Humic acids from decaying vegetation indicate currents that originated from land, triggering megalopae to sink lower and ride the salt water current into the bay. In some years, ocean winds and currents block the return flow, reducing the crab population - while in other years, hurricanes might push many larvae into the bay and lead to a boom year for crabs.

A hurricane can boost the blue crab population in the bay, by carrying a higher percentage of ocean-based larvae and megalopae past Cape Charles/Cape Henry and into the Chesapeake Bay. That same hurricane can damage the bay's oyster populations, bringing a surge of freshwater downstream and lowering salinity too long for upstream populations to survive.10

Though blue crabs could grow to 10 inches in size, few are larger than the legal harvest limit of 5 inches. Once they grow large enough, almost all mature crabs are harvested. While uncontrollable weather conditions trigger wide fluctuations in population levels, high fishing pressure limits the ability of the population to recover to target levels. That has led the Chesapeake Bay Foundation to renew its call for dealing with the two causes of population decline, over-harvest and reduction of suitable habitat:11

Managing the blue crab is an interstate challenge, and both Virginia and Maryland have questioned if the other state is doing its fair share to conserve the resource. Other states contribute to water quality challenges in the Chesapeake Bay, so every state in the watershed and the Federal government are involved in assuring compliance with the Clean Water Act. Since the crabs are not an endangered species, and only Virginia and Maryland issue licenses for crabbers to extract and sell blue crabs, determining acceptable levels for harvest - especially for female blue crabs - and ensuring compliance is an issue for just two states to resolve.

compared to a female crab (on left), a male crab known as a "jimmie" (on right) has a distinctively narrow abdomen

Source: Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Regulatory Fish Encyclopedia, RFE Page 1 for Callinectes sapidus, Blue Crab

Crab populations declined after the record harvest in 1993. In 1995, the National Marine Fisheries Service of the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration initiated the Chesapeake Bay Stock Assessment Committee to develop accurate population data, and to assess if the blue crabs were being over-harvested. In 1996, Virginia and Maryland created the Bi-State Blue Crab Advisory Committee to the Chesapeake Bay Commission, which the states had established in 1980 to coordinate bay-related activities, to assess how changed regulations would affect the number of crabs in the bay. In 1997 the Chesapeake Executive Council adopted a Blue Crab Fishery Management Plan with guiding principles, to serve as the framework for future decisions.

The Bi-State Blue Crab Advisory Committee provided a channel for intergovernmental discussions beyond what was available from the existing Potomac River Fisheries Commission (which issued crabbing licenses in just the Potomac River), and without the influence of Federal and state partners who were part of the Chesapeake Bay Program (created by the 1983 Chesapeake Bay Agreement).

By 2002, cooperation had increased sufficiently that Virginia stopped funding the bi-state committee when the state budget was affected by an economic recession. The major accomplishment of the committee before it died in 2003 was an agreement by both states to reduce crab harvests by 15%, plus increased collaboration that continued through other channels.12

Though blue crab larvae from the Delaware River may end up floating into the Chesapeake Bay, the blue crab population is not affected significantly by what happens in other states along the Atlantic Ocean seaboard. Unlike menhaden, the blue crab species is not managed by a multi-state fisheries plan under the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council.

before cooking, blue crabs are blue - after cooking, blue crabs are red

Source: Maryland Sea Grant and Maryland Seafood

Virginia and Maryland created the new Bi-State Blue Crab Advisory Committee bureaucracy so the two states could coordinate their regulations on harvest techniques and levels, and base their decisions on consistent data. The regulatory choices were especially challenging because:13

For a century, Maryland has lengthened its fall crabbing season so its watermen could catch more crabs migrating south, then negotiated with Virginia to limit that state's harvest of sponge crabs. When Virginia agreed to additional protection of sponge crabs, Maryland would agree to a shorter fall crabbing season. However, neither state was willing to accept the political and economic consequences of restricting harvest sufficiently to avoid the population crash that occurred in 2007.14

male blue crabs choose lower-saline waters away from the mouth of the bay, so Maryland watermen harvest more males than females

Source: Chesapeake Bay Stock Assessment Committee, 2012 Blue Crab Advisory Report

Figures

Blue crabs in the Chesapeake Bay are one population spread across two states. A fundamental bi-state management issue was the winter dredging conducted by Virginia crabbers. Maryland required crabbers to use pots and did not allow dredging which scraped the bottom and damaged submerged aquatic vegetation, reducing habitat. Virginia watermen caught most of their crabs via pots, but dredges were utilized in the winter when the crabs moved to deeper waters.

Most importantly, Maryland wanted to protect pregnant females near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, which were the target of Virginia's watermen during the winter dredge season. Maryland wanted fertilized females to survive and spawn the following spring, to increase the potential number of crabs that could grow to maturity, so Maryland regulators advocated for a change in Virginia's regulations that might help increase total crab numbers throughout the bay.

Virginia regulators were well aware that a ban on winter dredging might affect population totals - and such a ban would have no economic impact on Maryland watermen. Because pregnant females migrated south of the state border into Virginia, any restriction of their harvest would impact only Virginia watermen.

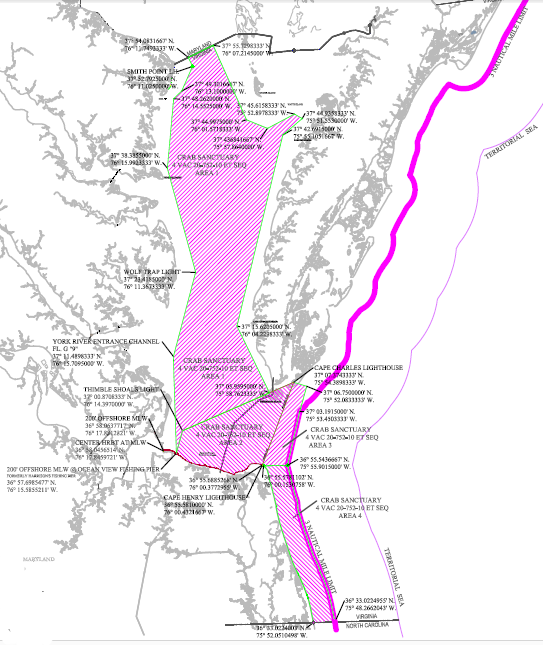

The winter dredge season filled a gap between opportunities to harvest other species, so there was strong pressure from Virginia watermen to continue traditional harvesting. In 2000, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) created the Virginia Blue Crab Sanctuary, banning all harvest between June 1-September 15. The sanctuary enabled female crabs to migrate south to a 600-square mile, 55-mile-long by 10-mile-wide deep-water sanctuary, putting off-limits all of the bay bottom in Virginia over 35' deep. The sanctuary was expanded to 900 square miles in 2002, block harvest in all Virginia water at least 30' deep.15

A Virginia Institute of Marine Science fisheries ecologist had noted just before the population crash in 2007:16

The limited value of the sanctuary was not just that crabs could be caught before reaching the protected area; the designated sanctuary was only for the summer migration time. After reaching the sanctuary, crabs were still at risk. Pregnant females that over-wintered by burrowing in the mud of the bay's bottom could still be harvested during the winter months, because Virginia officials authorized a winter dredging season.

After the declaration of an economic disaster in 2008, blue crab harvest levels were cut by 34%. The Virginia Marine Resources Commission finally passed a ban on winter dredging, and Maryland limited its fall harvest in return.

The economic impact of the dredging ban on the 58 holders of winter dredge permits was mitigated by $10 million in funding to Virginia from the Federal government. That disaster relief was used to "buy out" crab fishing operators, collect abandoned "ghost pots" that were catching and killing 50 crabs/year, and encourage a shift to oyster aquaculture.17

the Virginia Marine Resources Commission allows harvest of crabs ready to spawn, until the eggs mature and the sponge shifts from orange to brown

Source: Virginia Marine Resources Commission, Regulation: Sponge Crabs

The Maryland-Virginia disagreement on the priority of protecting the winter population of female crabs near the mouth of the bay has continued. In 2012, during a boom in crabs, Virginia extended the harvest season an extra week in December (with the support of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation). Virginia's regulators rejected requests from Maryland officials to protect the crabs that would spawn the following spring.

the Winter Blue Crab Dredge Survey showed the number of spawning-age female blue crabs was often below the target, and occasionally below the "unsustainable" threshold

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, 2016 Chesapeake Bay Blue Crab Advisory Report (p.3)

In 2013, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission considered re-opening the winter dredge season, but in the end declined to do so. A year later, it renewed the ban and lowered the harvest level of female crabs by 10%, after the 2014 Annual Winter Dredge Survey showed the number of female blue crabs had dropped below the safe level of 70 million.18

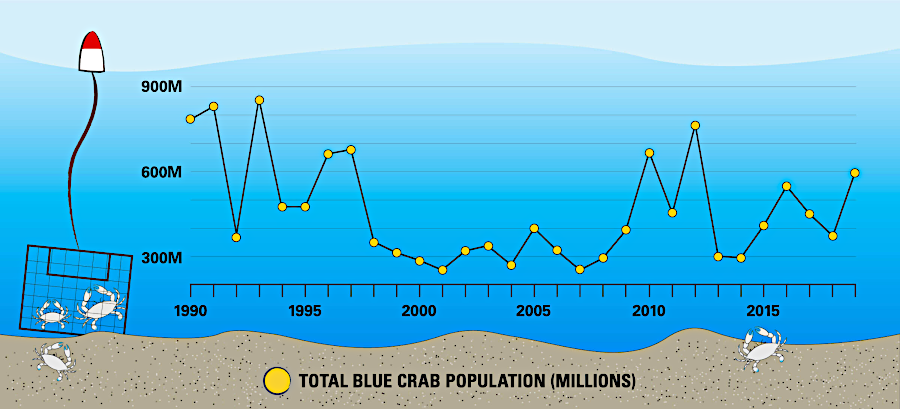

the total number of blue crabs has not recovered to the levels in the 1990's

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, Blue Crabs

The 2014 harvest by watermen was a record low. Submerged aquatic vegetation declined substantially after 2012, while there was an increase in the population of red drum - a fish that eats juvenile crabs. A member of the Virginia Marine Resources Commission noted:19

Survey Year (Year Survey Ended) | Total Number of Crabs in Millions (All Ages and Both Sexes) | Number of Spawning Age Female Crabs (in Millions) | Percentage of Female Crabs Harvested (female exploitation fraction) |

1990 | 791 | 117 | 44 |

1991 | 828 | 227 | 34 |

1992 | 367 | 167 | 60 |

1993 | 852 | 177 | 35 |

1994 | 487 | 102 | 28 |

1995 | 487 | 80 | 32 |

1996 | 661 | 108 | 20 |

1997 | 680 | 93 | 22 |

1998 | 353 | 106 | 40 |

1999 | 308 | 53 | 37 |

2000 | 281 | 93 | 43 |

2001 | 254 | 61 | 42 |

2002 | 315 | 55 | 34 |

2003 | 334 | 84 | 33 |

2004 | 270 | 82 | 42 |

2005 | 400 | 110 | 24 |

2006 | 313 | 85 | 29 |

2007 | 251 | 89 | 35 |

2008 | 293 | 91 | 24 |

2009 | 396 | 162 | 23 |

2010 | 663 | 246 | 18 |

2011 | 452 | 191 | 24 |

2012 | 765 | 95 | 10 |

2013 | 300 | 147 | 23 |

2014 | 297 | 69 | 17 |

2015 | 411 | 101 | 15 |

2016 | 553 | 194 | 16 |

2017 | 455 | 254 | 21 |

2018 | 371 | 147 | 23 |

2019 | 594 | 191 | 17 |

2020 | 405 | 141 | 19 |

2021 | 282 | 158 | 26 |

2022 | 227 | 97 | 22 |

2023 | 323 | 152 | - |

2024 | 317 | 133 | - |

2025 | 238 | 108 | - |

Blue Crabs recovered after the low 2014 harvest. The 2015 winter dredge survey, done between December, 2015-March, 2016 at 1,500 sampling sites, showed substantial increases. The total number of crabs were even higher in the 2016 report.

The Virginia Marine Resources Commission noted in April, 2016 that over the last year:20

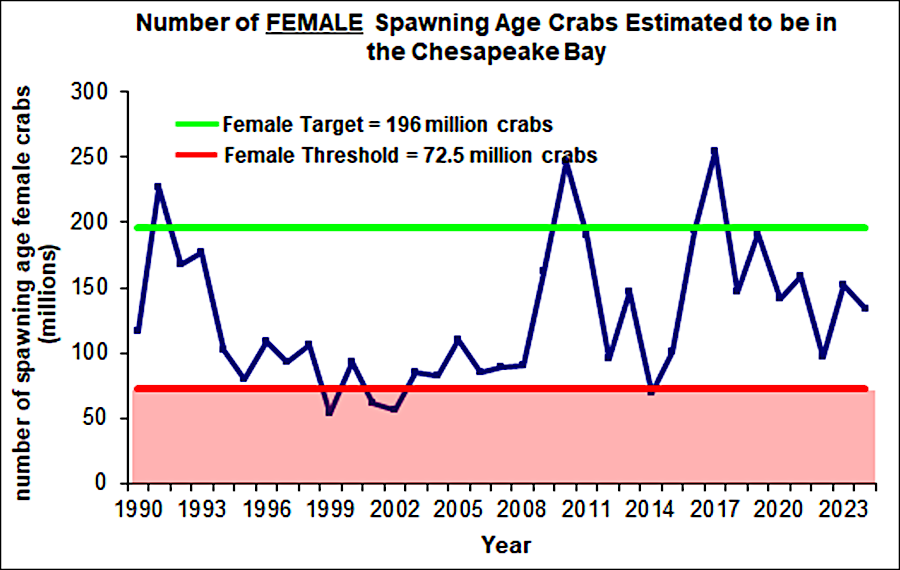

the population of female blue crabs increased after Virginia and Maryland established female-specific benchmarks

Source: Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR), At Another Key Juncture for Blue Crabs, Scientists Look Back at Two Decades of Management (June 18, 2024)

The report for the following year estimated that the number of spawning age female crabs dropped 18% in 2017, and fisheries manages projected that 35% of adult females had died over the 2017-18 winter. However, the estimate of 254 million adult females counted in the December, 2016-March, 2017 winter dredge survey remained well above the minimum safe number of 215 million. Because juvenile crabs increased 34%, the managers remained optimistic that restoration efforts were having a positive impact.

A waterman who been crabbing in the Chesapeake since 1968 noted in 2024:21

The blue crab population varies substantially each year, and identifying a trend is complicated. The December, 2017-March, 2018 survey produced a population estimate of only 147 million spawning females, below the minimum safe number. The December, 2018-March, 2019 survey found 190 million spawning females, still below the minimum safe number of 215 million.22

The annual winter dredge survey in December, 2020-March, 2021 determined that there were 158 million spawning females. That was below the target of 196 million crabs, and there was a greater than 50% decline in juvenile numbers. The number of juveniles was the lowest number since the annual Baywide survey began in 1990. Even though the crab harvest had dropped 25% due to the reduction in demand due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the total number of crabs was the lowest since 2007.

With the large number of spawning females, the number of juveniles could recover if there were favorable coastal conditions for larvae released near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay in late 2021. Regulators did not increase the authorized crab harvest in 2021, but did not feel that a reduction was needed either. The primary concern of the regulators was the low number of adult male crabs available to fertilize eggs. The population of 39 million was far below the long-term average of 77 million adult male crabs.23

Conflicting Maryland-Virginia approaches to managing the blue crab resource were revealed in 2024, after Virginia relaxed a ban imposed in 2008 on winter dredging of semi-dormant crabs overwintering in the mud on the bottom of the Chesapeake Bay. The normal harvest season is April-November. On June 25, 2024, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) voted 5-4 to authorize winter dredging. Summer harvest limits would be reduced, so the extended season would not increase the total annual harvest from Virginia waters.

Staff at the Virginia Marine Resources Commission had recommended maintaining the ban, anticipating a new Chesapeake Bay Stock Assessment that would be published in March 2026 which could guide new harvest regulations. For example, new regulations could include limiting the harvest of "jimmies" in areas with so few males that females could not mate. A new winter dredge season would affect the population numbers, complicating the ability of scientists to project impacts of harvest regulations on the crab population.

The 2022 winter dredge survey estimated the total number of crabs in the Bay was below the historic 2007 low. Data released in 2024 showed below-average recruitment (survival of juvenile crabs) for the fifth year in a row. Recruitment data is the best indicator of the Chesapeake Bay blue crab's population health. The satisfactory population numbers of over-wintering females were not producing enough juveniles to restock the Chesapeake Bay with a new generation of blue crabs in order to maintain a sustainable fishery. It was unclear if weather, blue catfish predation, or some other factor was limiting recruitment.

2024 data showed the population of juvenile crabs had been below average for five consecutive years

Source: Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR), At Another Key Juncture for Blue Crabs, Scientists Look Back at Two Decades of Management (June 18, 2024)

Crabs caught in the winter could be sold for higher prices and help more watermen make a living by working in the Chesapeake Bay - but only Virginia watermen would benefit. Maryland officials also worried about a reduction in the summer population when crabs migrated north across the state line, since the winter harvest would be almost entirely females.

Maryland officials made their objection to Virginia's unilateral action very clear, but there was no mechanism that would allow Maryland officials to overturn a decision by the Commonwealth of Virginia agency. The bi-state cooperation was not overseen by a Federal organization to which Maryland could appeal. The Potomac River Fisheries Commission coordinated the crab management plan adopted in 2008 which banned winter dredging, but had no veto power.

The Maryland Executive Director for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation was clear in Virginia's action:24

Though the Virginia Marine Resources Commission suggested the winter dredge season might be shorter than the traditional December 1-March 31 length, Maryland Department of Natural Resources Secretary Josh Kurtz expressed his disappointment bluntly:25

harvesting female crabs in winter eliminates the potential for her eggs to become juvenile crabs in the spring

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), Dredge Survey Methods

Just a week earlier the director of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources Fishing and Boating Services had assessed the success of the cooperative planning and management decisions made after the blue crab population dropped by over 60% between 1998-2008 and the U.S. Department of Commerce issues a disaster declaration for the fishery in 2008. Based on a 2011 "stock assessment" of the blue crab population that established female-specific reference points for sustainable yield, the two states had issued regulations which reduced the harvest rate of female blue crabs by one-third.

Bi-state studies and regulations had led to the recovery rather than the continued depletion of the blue crab population. Ironically, just a week before the vote by the Virginia Marine Resources Commission a Maryland official had highlighted how effective partnerships had been essential in changing the trend line since 2008:26

the Virginia Blue Crab Sanctuary first created in 2000 was intended to protect female crabs during their spawning migration - not to ban winter dredging

Source: Virginia Marine Resources Commission, Map of Proposed Blue Crab Sanctuary

by 2012, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission had expanded substantially the boundaries of the Virginia Blue Crab Sanctuary... but crabbing was still limited only between May-September

Source: Virginia Marine Resources Commission, Virginia Blue Crab Sanctuary (October 2012)

In September 2024, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission reversed its decision and chose to keep the winter dredge crabbing season closed. To accommodate watermen's desire to harvest more crabs, the state agency chose instead to extend the pot catching season an extra month to the end of December. Due to warmer temperatures, more crabs were expected to be active in December rather than buried in the sediments of the Chesapeake Bay.

The Virginia Twin Rivers Waterman's Association, which was composed of crabbers on the Rappahannock and Potomac Rivers, commented:27

The level of legitimate harvests are affected by the unplanned capture by "ghost" crab pots. The Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) estimates that 20% of pots are lost each year, typically due to storms and lines being cut by passing boats. That adds 145,000 pots which crabs can never escape to the bottom of the Chesapeake Bay annually.

In 2023, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) awarded the College of William and Mary an $8 million grant to remove derelict fishing gear from the Chesapeake Bay and tidal rivers. State funding to remove ghost posts had been used once before. During an economic downturn when Tim Kaine was Governor, 34,000 traps were removed during the winter season over six years. In addition to enhancing the crab population, that project helped employ watermen when the crab season was closed.28

The future of the blue crab population in the Chesapeake Bay will be affected by climate change. The 117 days of winter experienced now is projected to decline to 90 days in the year 2100, and perhaps to only 60 days. A shorter winter will give juvenile blue crabs extra time to feed, increasing their over-winter survival from 75% to nearly 100%.

By 2023, blue crabs were already mating in the Gulf of Maine and expanding their habitat to the north. The species will be a "climate change winner" initially, until southern predators migrate north. Predators will take advantage of the changed climate as well, reducing the population of blue crabs. In addition, the warmer temperatures may reduce the number of Baltic clams upon which the crabs feed, also lowering their population after the initial spike.29

megalopae, the last larval stage prior to molting into a juvenile crab

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration - Ocean Explorer, Sponge Commensals: A Life Inside Another Organism

Percentage of Female Crabs Harvested (female exploitation fraction) has often exceeded the 34% now defined as the maximum for sustainable harvest

Source: Virginia Marine Resources Commission, Virginia Marine Resources Commission Adopts New Blue Crab Fisheries Regulations (June 24, 2014)