Brood X of the 17-year periodical cicada emerged in Northern Virginia in 2004

Source: Environmental Protection Agency, A Return of the Cicadas (Part 1)

Brood X of the 17-year periodical cicada emerged in Northern Virginia in 2004

Source: Environmental Protection Agency, A Return of the Cicadas (Part 1)

There are over 150 species and over 20 subspecies of cicadas in North America. "Singing" cicadas evolved at least 59-56 million years ago.1

Adult female cicadas are quiet, but the males noisily drum by vibrating the sides of their abdomen. Female cicadas choose one of those drumming males, mate, then insert 24-28 eggs into the tips of tree branches. Eggs hatch a few weeks later, and the first larval stage ("instar") drops to the ground. The small cicada nymph quickly digs underneath the surface to hide from predators and to find tree roots. Larvae are herbivores and "true bugs" that use their beaks ("rostrums") to feed on tree sap. The beaks penetrate cells in the roots, allowing the nymph to intercept water with sugars and amino acids that is moving the leaves down to underground roots.

Different species of cicadas prefer different tree hosts. Adults of different species produce sounds at different frequencies and in different patterns to attract a mate from the appropriate species.

female cicadas cut a slit in tree branches, into which they deposit their eggs

Source: Wikimedia Commons, Magicicada septendecim

A cicada nymph that drops from a tree branch will split its skin ("ecdysis") four times while underground, in order to grow. The fifth instar of the larvae crawls to the surface and finds something to climb at night, when predators can not see it. After a climb several feet above the ground to the safety of lower tree limbs, the last instar pauses to shed its outer skin. It takes several hours to complete the metamorphosis into a winged adult. The last skins (exoskeletons) appear on tree trunks as dry molds of cicadas.

Unlike Monarch butterflies, cicadas do not create a pupa. Monarchs transform their bodies within the protective shell of the pupa during a period of inactivity. Cicadas are different. The eggs of periodical cicadas hatch in late July/August. The nymphs emerge and then drop to the ground. Though there may be billions of nymphs falling down, people underneath will not notice because the nymphs are so small and light.

cicadas emerge from the ground as nymphs, climb vertical surfaces, and split their skins to become winged adults

Source: Pixabay (by Dan Keck)

cicadas leave their last instar skin as a dry exoskeleton, before flying away on new wings

Source: Pixabay (by Philip Wels)

Of them, seven species in the Magicicada genus are periodical cicadas which spend 13 or 17 years underground before emerging and starting to call. Today there are three species with a 17-year life cycle, Magicicada septendecim, Magicicada cassini, and Magicicada septendecula. There are four species with a 13-year life cycle, Magicicada tredecim, Magicicada neotredecim, Magicicada tredecassini, and Magicicada tredecula.

The "septen" in the species names reflects the 17-year life cycle, while the "tre" refers to the 13-year pattern. Each group has a "decim," "cassini," and "decula" species group, and the 13-year cicadas have also evolved into a "neotredecim" species. Each eruption of a 17-year brood includes all three species in that group, and each eruption of a 13-year brood includes all four species in that group.

Genetic studies of the seven Magicicada species east of the Mississippi River reveal that that they evolved from a last common ancestor. The "decim" species apparently diverged from the ancestor of a combined "cassini + decula" species 3.9 million years ago. The "cassini" and "decula" species separated 2.5 million years ago. Then a group of 17-year Magicicada septendecim cicadas hybridized with a 13-year brood and evolved into the Magicicada neotredecim species with a 13-year cycle.

When the species initially separated, they did not have 13-year and 17-year broods. That pattern developed in response to climate changes when ice sheets advanced. Smaller populations of cicadas in the reduced habitat were under greater pressure from predators. Predator saturation was a successful survival technique. It is even possible that bird populations cycle down to a low point when the broods emerge, enhancing the survival potential of the insects. Though statistics indicate at least a correlation between bird population declines and timing of brood emergence, any mechanism of causation is a mystery. It is unknown how cicadas could depress the bird population 13 or 17 years later within the range of a brood's emergence.

As broods emerge, some matings mix genes between the species and evolutionary changes are still occurring. At places where emergence of 13-year and 17-year broods overlap, sometimes a particular life cycle will breed more successfully and the range of a brood will expand.2

Most publicity regarding cicadas is concentrated on the periodical broods. The long gap between emergences results in a generation of teenagers who have never experienced the phenomenon, and even adults have few experiences to remember.

Virginia has 25 species and subspecies of both annual and periodic cicadas. Annual cicadas belonging to the genus Neotibicen will mature and emerge every year in June-August. Due to the omnipresent drone during hot summer afternoons, the "Northern Dusk Singing Cicada" is also called the "dog days cicada." The females lay eggs in dead wood.

Males do all the calling, starting after dawn and finishing at dusk. They rarely call at night; night sounds are produced by crickets, katydids, and frogs. The high-pitched squeal near someone's ear at dusk is normally from a mosquito. Individual adult cicadas live for several weeks, and with different emergence dates the mating hum can last for about six weeks between May-July. About the time the periodical cicadas disappear, the annual cicadas begin their calling.

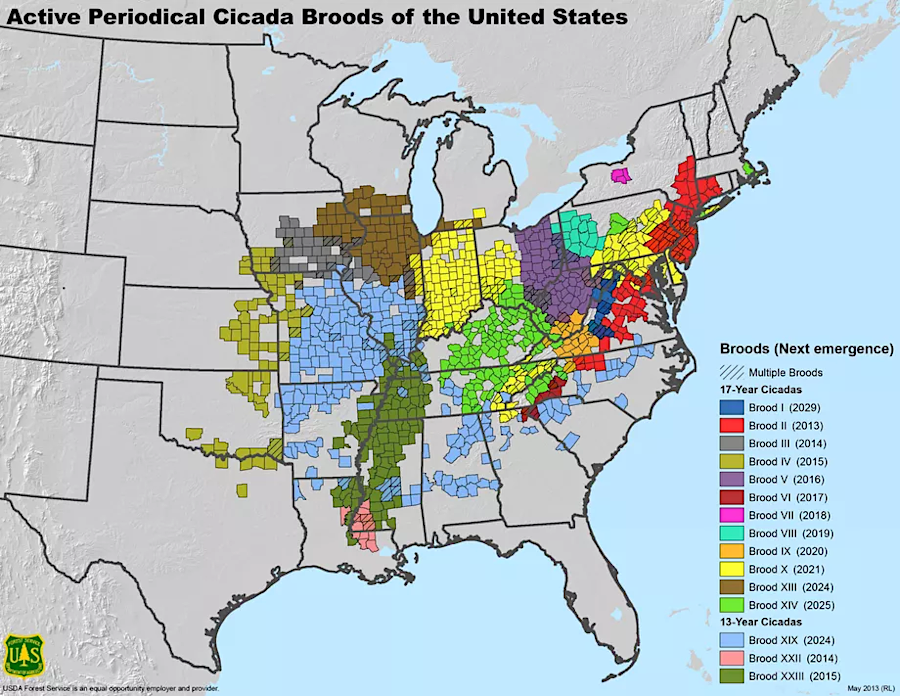

There are 15 broods of periodic cicadas, whose lives are synchronized on a 13-year or 17-year cycle. There are 12 broods of 17-year cicadas and three broods of 13-year cicadas.

The Magicicada species emerge once the soil temperature eight inches underground warms up to 64°F. When a brood is ready to emerge after 13 or 17 years, the nymphs typically crawl out of the soil over a two-week period. This occurs in May in Virginia, a month later than in Alabama. As many as 1.5 million cicadas may emerge per acre when a brood hits the right age.

The annual cicadas are green with black eyes. Periodical cicadas are relatively easy to spot in the trees, with bright red eyes. Both annual and periodical cicadas lack defensive tools; they can not bite or sting, and are not poisonous. The two types use different survival strategies.

Annual cicadas use their green camouflage to hide from predators. Periodical cicadas rely upon "predator saturation." The sheer volume of periodical cicadas overwhelms the appetites of predators. As many as one million periodical cicadas can emerge on just one acre, or 25 or 30 bugs per square foot.

Despite gorging by birds, raccoons, skunks, and other animals, the predator saturation technique is effective. Enough periodical cicadas will survive to lay eggs and ensure another generation. The 13-year and 17-year emergence cycles are prime numbers, so there is no predator population increase in anticipation by a species with a regular pattern of population surges based on 2-year, 3-year, or 5-year cycles.

periodical cicadas get special attention because the massive numbers (as many as 1.5 million cicadas emerging per acre) create massive noise levels

Source: Flicker, Periodical Cicada (Magicicada septendecim) (by JanetandPhil)

The females lay eggs in live wood, and prefer oak species. When they cut into twigs with their ovipositor to lay eggs, the nutrients stop flowing to the tips of tree branches. In September, one sign of a heavy periodical cicada emergence in an area will be dead twigs on oak trees, a pattern known as "flagging." The damage to vegetation is short-term, akin to grazing by deer.3

The broods were identified with Roman numerals by a US Department of Agriculture entomologist in 1893, but the cyclical pattern of the periodical cicadas was already recognized. Massachusetts colonists had noted in 1634 "a numerous company of Flies, which were like for bigness unto Wasps or Bumble-Bee" and how the tips of tree branches were killed:4

In the eastern states, there are three broods of the 13-year cicadas. Virginia experiences only Brood XIX emergence, with all four species: Magicicada tredecim, M. neotredecim, M. tredecassini, and M. tredecula. The cycle for Brood XIX emergence is 1972, 1985, 1998, 2011, 2024, and 2037, but some can appear as much as four years early.

The genes of periodical cicadas include a clock that determines when the nymphs will emerge and metamorphose into adults. The nymphs apparently recognize the passage of the years by changes in the flow of sap between summer and winter. Global warming may be triggering the broods to emerge early, and genetic variability results in stragglers. That creates the potential for a brood to continue if a standard emergence year coincides with a disaster such as a hurricane or drought. In addition, where brood emergences overlap there may be gene transfer.

annual cicadas blend into the vegetation, while periodical cicadas rely upon "predator saturation" to ensure enough will breed successfully each 13-year or 17-year cycle

Source: Flicker, Neotibicen linnei linne's annual cicada (by Tibor Nagy)

Of the 17-year cicadas, Brood X is the most widely distributed in the United States. The "Great Eastern Brood" emerges from New York to Georgia. It has three epicenters - the Washington DC region, south-central Indiana, and the Knoxville Tennessee area.

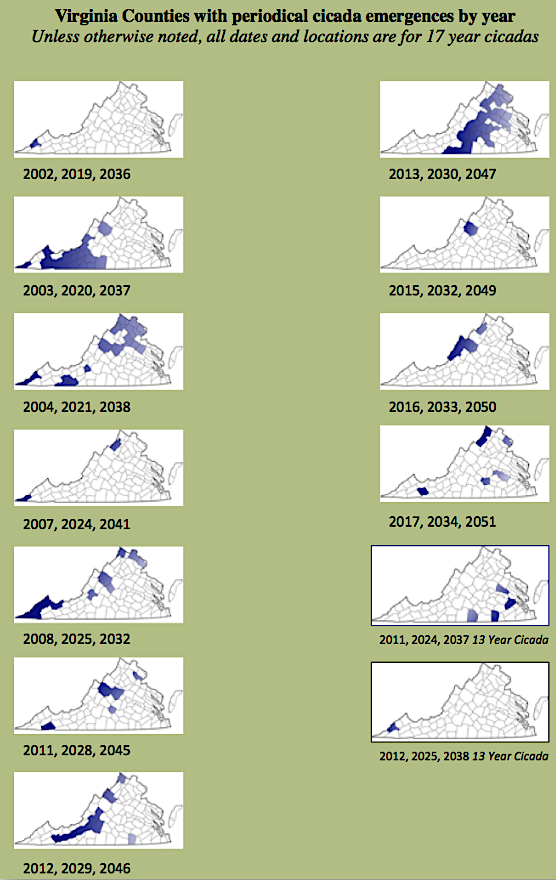

Broods I, II, IX, X, and XIV emerge in different parts of Virginia on the following cycles:5

Brood I - 1961, 1978, 1995, 2012, 2029, 2046

Brood II - 1962, 1979, 1996, 2013, 2030, 2047

Brood IX - 1952, 1969, 1986, 2003, 2020, 2037

Brood X - 1953, 1970, 1987, 2004, 2021, 2038

Brood XIV - 1957, 1974, 1991, 2008, 2025, 2042

The males that emerge each year create the tradition evening background sound of summer in Virginia; long-time residents can distinguish the hum of annual cicadas in July from the overwhelming cacophony of the periodical broods in early June. All male cicadas use their muscles (not their legs) to vibrate two drum-like plates (tymbals), one on each side of their abdomen, 300-400 times per second. Females as much as a mile away can be attracted by "the loudest song in the insect world."6

The 17-year cicadas are Virginia's longest-living insect. No other insect species has a life cycle that long. The nymphs from Brood X cicadas that emerged in 2021 will not reappear until 2038, four presidential elections later.7

Male cicadas make their noise for just one reason: to find a mate, after living a solitary life for 13 or 17 years. One biologist anthropomorphized the yearnings and behavior of the males:8

annual cicadas appear every year, while different broods of periodical cicadas appear in Virginia on specific 13-year and 17-year cycles

Source: US Forest Service, Periodical Cicadas

In the suburbs of Northern Virginia and elsewhere, new neighborhoods will not hear many periodical cicadas. Construction projects disturb the soil and kill the underground cicadas, as roads and houses are built. In the "tree save" areas and in forests not yet disturbed, some cicada nymphs may survive and enable the local population to recover.

The nymphs do little damage to the roots; they may even improve the soil by aerating it. Cicadas can survive on the nutrient-poor sap only because they have a symbiotic relationship with specialized bacteria that produce additional proteins.9

In 2024, Brood XIX was scheduled to emerge in Virginia while Illinois and Indiana would see the rare emergence of both Brood XIX and Brood XIII. That double emergence had not occurred since 1803, when Thomas Jefferson was serving his first term as President.10

where 13-year and 17-year periodical cicada broods emerge in Virginia

Source: Virginia Cooperative Extension, Periodical Cicadas