The Susquehannock in Virginia

when the English colonists first arrived, the Susquehannock were contesting with the Iroquois for control over the Susquehanna River valley and expanding their territory south to the Potomac River

Source: Library of Congress, Carte de la Louisiane et du cours du Mississippi (1718)

The Susquehannock, an Iroquoian-speaking tribe, originally lived on the North Branch of the Susquehanna River north of modern-day Scranton, Pennsylvania. They may have evolved from the same ancestral group as the Mohawk and Cayuga. Sometime before 1570, the Susquehannock moved south to what later became Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. They may have displaced the Shenks Ferry people as early as 1450.

Their territory was bordered on the west by the Erie, on the north by the Iroquois, on the east by the Delaware (Lenni Lenape), and on the south by the Piscataway.

When the Maryland colonists arrived in 1632 on the Ark and Dove, the Susquehannocks were pushing the Piscataway out of their traditional territory on the Potomac River.

During the colonial era, the Susquehannock were not permanent residents in the lower Chesapeake Bay. Their presence in what ultimately became Virginia consisted primarily of short-term camps for hunting expeditions. Warriors also traveled down the Chesapeake Bay and through the Piedmont, raiding rival tribes as well as hunting. After the founding of Maryland, they began attacking farms of colonists who were expanding into the backcountry.

The Susquehannocks started trading deerskins and furs with the Dutch at Manhattan as early as 1626, and obtained plentiful supplies of weapons from different European competitors. For many decades, the Susquehannocks were a serious threat to the Mohawks at the "eastern door" of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy and even to the Seneca nation at the "western door."1

When furs and skins became harder to acquire due to excessive market hunting, the tribes near the European trading posts at Montreal, Albany, and the Chesapeake Bay sought to control the supply from more-distant tribes. The French, English, and Dutch tried to bypass Native American groups that served as intermediaries, and played one group against another. The resulting intertribal conflict, stimulated by the existential need to obtain guns from the Europeans and the benefits from trading in cloth and other goods, was fierce.

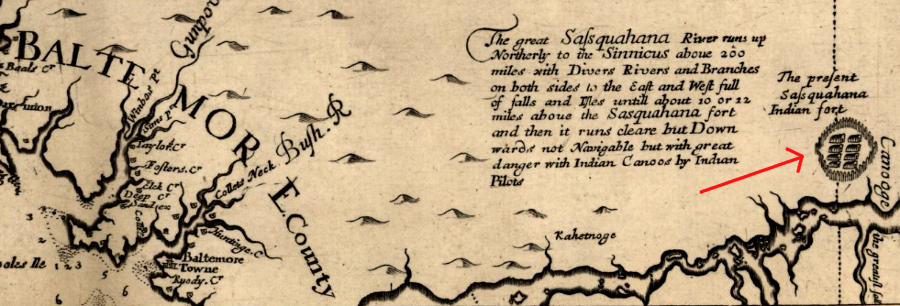

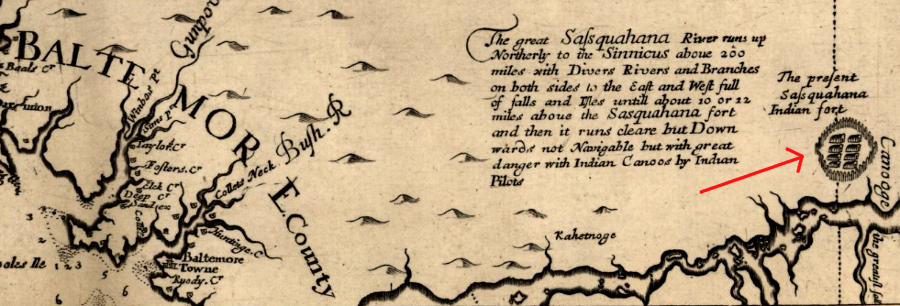

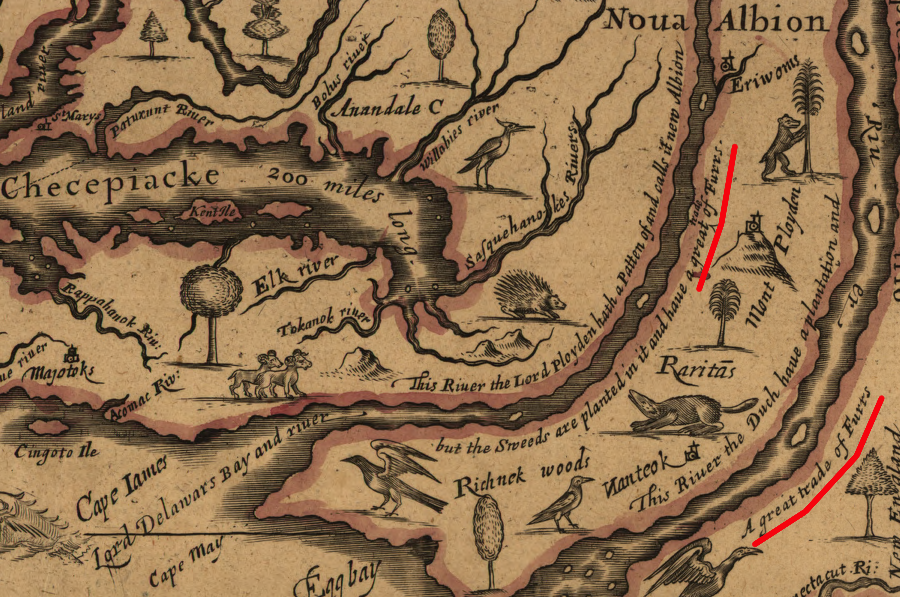

the Susquehannock with their fort controlled the fur trade in the Susquehanna River valley in 1670, before the Iroquois made them subordinate

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 (by Augustine Herrman)

In the 1630's William Claiborne set up a fur-trading station at Kent Island in the Chesapeake Bay. That location made it easy for the Susquehannocks to obtain prestige goods, tools, guns, ammunition, and gunpowder from the Virginia colony to the south.

When Claiborne first occupied Kent Island, it was located within the boundaries of the Virginia colony based at Jamestown. He continued to trade with the Susquehannocks despite the creation of a new Maryland colony in 1632 and the arrival in 1634 of Governor Cecil Calvert with permanent settlers on the Ark and Dove.

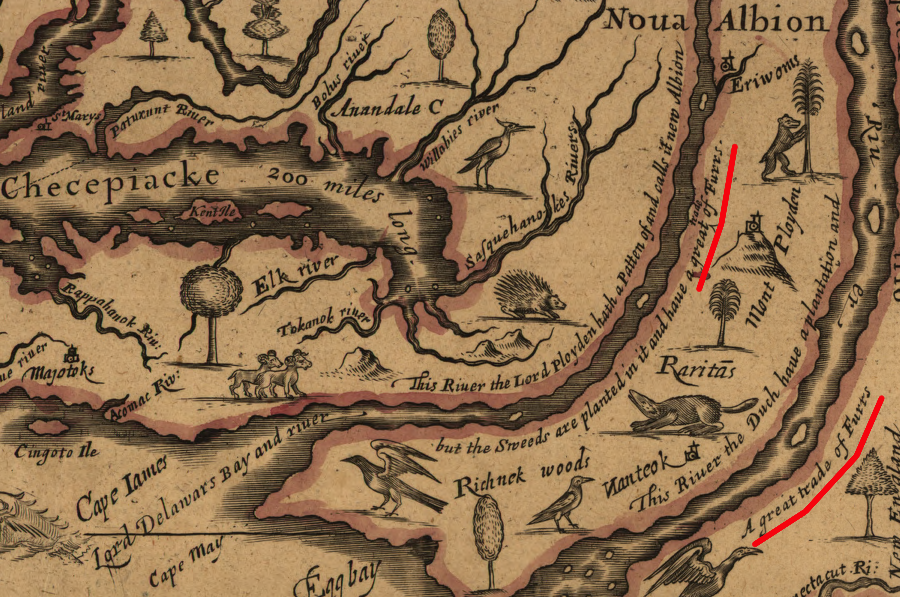

the fur trade along the Delaware and Hudson rivers was important, especially to Virginia colonist William Claiborne in the 1630's

Source: Library of Congress, A mapp of Virginia discovered to ye hills (John Farrer/John Overton, 1667)

The Marylanders soon displaced various Native American groups along the Potomac River and gained control over the towns of the Piscataway confederacy. Lord Calvert evicted William Claiborne from Kent Island in 1638, though that Virginian continued to disrupt relations within the colony and with his Susquehannock fur-trading allies.

Also in 1638, Swedish traders built Fort Christina at the site of modern Wilmington, Delaware. The Swedes joined in the regional competition for furs, but lacked influence with Native American groups already doing business with the French, Dutch, and English. To compensate, the Swedes were willing to sell more ammunition and gunpowder to Native Americans than the other European groups. The other Europeans had sold guns widely, but controlled sales of ammunition/gunpowder to limit the military capacity of the Native Americans. Thanks to the unlimited arms sales by the Swedes, Maryland officials could not defeat the Susquehannocks in the 1640's.2

Both Maryland and the Susquehannocks finally chose the alternative to fighting and conquest - trading. The Calverts were temporarily displaced during the English Civil War, and in the early 1650's William Claiborne and his allies took control of the colony.

At that time, the Mohawks were raiding to the south and threatening the rival tribes along the Susquehanna and Potomac rivers. Jesuit missionaries were forced to abandon their mission at Piscataway Creek in 1642. Claiborne could negotiate with the Susquehannocks, his Native American partners in the fur trade, in ways the Calverts could/would not, and both sides agreed to a peace in 1652.

The Susquehannock nation needed peace in 1652 in order to focus on the Mohawk threat from the north. From the colonists' point of view, peace always increased opportunities to gain wealth by trading furs and to harvest tobacco/corn crops without disturbance. Fortified Susquehannock towns could be a useful barrier for the colonists against raids by the "Seneca" (used as a common shorthand to describe any of the five nations in the Haudenosaunee Confederacy), Nanticokes (Delaware), and other groups.

Peace also reduced the risk that the Susquehannock nation would be incentivized by the Swedes/Dutch on the Delaware River to attack English settlements. Maryland could not depend reliably upon Virginia to come to its aid if attacked, reflecting the competition between the two colonies for land along the upper Chesapeake Bay and the objections in Virginia to a Catholic settlement in the region.3

The threat from the Delaware River changed after Dutch seized New Sweden in 1655, then surrendered their colony of New Netherland to the English in 1664. The brother of King Charles II, James (Duke of York), claimed all the Dutch settlements as part of his colony of New York. In 1673, during the Third Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch briefly recaptured their settlements on the Delaware River.

To counter that threat and the risk of Mohawk attack, the Maryland General Assembly passed a special tax in 1673 to provide gunpowder to the Susquehannocks. With supplies from Maryland, the Susquehannocks raided to the north of the future New York-Pennsylvania boundary and came close to defeating the Five Nations.

Maryland colonists hoped the Susquehannocks would become fighting allies, serving to protect English colonists from rival groups. Native Americans were forced to choose between becoming subordinate "tributary" tribes (who in most cases lost their land and culture), open enemies of the colonists (who in most cases were destroyed in wars), or essentially mercenary soldiers for the colonists.4

the willingness of Dutch settlers at New Flanders ("La Novvelle Flandre") to sell weapons helped the Susquehannock, Iroquois, and other Native American groups bargain with the English nearby and the French at Montreal

Source: University of Ottawa, Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-francaise, Carte de la Nouvelle-France (c. 1641)

The Dutch abandoned their North American settlements in 1674, but the Calvert claim to lands on the eastern edge of the Maryland colony remained threatened by the officials in New York who were sponsored by James, the Duke of York and brother of King Charles II. To assert more control over the Susquehannocks (and possibly prepare for seizure of the lands along the Delaware River), Gov. Charles Calvert convinced them to move closer to the Potomac River.

The invitation was for the Susquehannocks to settle near Little Falls/Great Falls, upstream of modern Washington DC. New York-based traders would have less influence there, and a fortified Susquehannock town on the Potomac River would serve as a barrier between the Iroquois and Maryland's settlers.5

That move was disastrous for the Susquehannock nation, and ultimately for Virginia's long-serving governor William Berkeley.

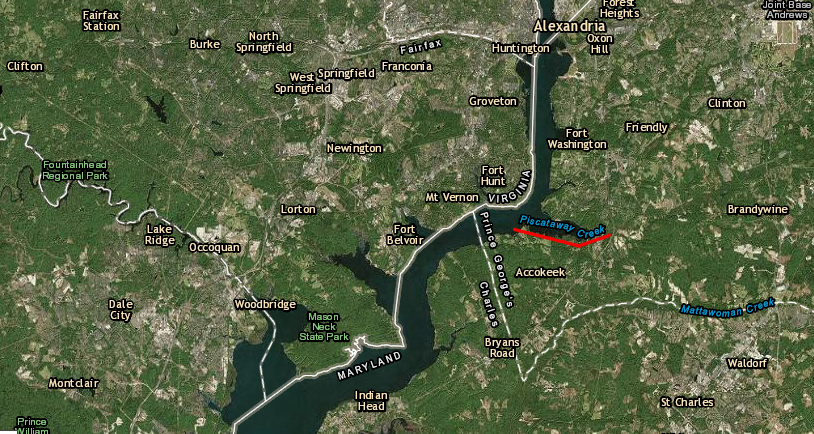

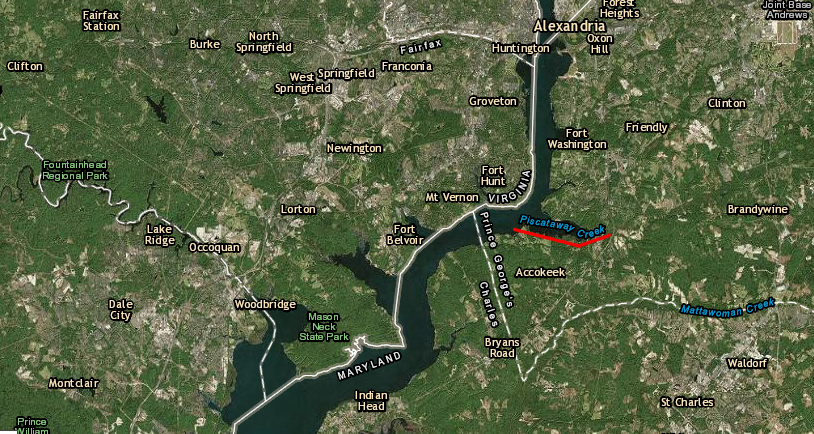

the Susquehannocks settled on Piscataway Creek, after the Maryland colony convinced them to move west to the Potomac River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Major Edmund Andros, the governor of New York, was an ally of the Iroquois according to the Covenant Chain. Once the Susquehannock moved, he converted the Delaware (Lenni-Lenape) into allies of the New York colony. That increased New York's claim to the land that later became the state of Delaware, and undercut the previous support provided by the Delaware to the Susquehannocks.

The Susquehannock ignored the invitation to locate near Little Falls/Great Falls, and instead built a fortified town at the mouth of Piscataway Creek. It is not clear if the Piscataways who already lived in the area welcomed or opposed the relocation, but the could not block it.

The Susquehannock fort was across the Potomac River from land patented by Col. John Washington (property that later became George Washington's Mount Vernon). The Virginians were expanding up the Potomac River, displacing the Dogues and other Native Americans who had traditionally used the lands north of the Rappahannock River. Augustine Herrman's 1670 map shows that at least a portion of the Dogue had relocated to the Rappahannock River, downstream from the Fall Line.

Herrman's map also shows nearby communities of the Portobaco and Chingwateick. They may have been refugees from Maryland who were unhappy with the 1666 "articles of peace and amity" signed by Gov. Calvert with 12 separate Native American groups, and the planned reservation (which would exclude visits from "forreign Indians" such as the Iroquois) surveyed between Mattawoman and Piscataway creeks in 1669.

The governor's efforts to establish more control may have initiated the shift of the Anacostin upstream from the confluence of the Anacostia/Potomac rivers to Anacostin Island, even though the new location was more exposed to attack by the Iroquois.6

Maryland's efforts to control the Susquehannock, Piscataway, and Dogue stimulated a migration of Native Americans to the Rappahannock River, prior to Baccon's Rebellion in 1676

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 (by Augustine Herrman)

In 1675, members of the Dogue tribe felt cheated by a Virginia colonist and took hogs from Thomas Mathews. In a series of incidents, Virginians and Dogues retaliation grew into a borderland war that involved the Susquehannock. Col. John Washington led a Virginia raiding party across the Potomac River into Maryland and attacked the Susquehannock fort at Piscataway Creek, claiming the Dogue were being sheltered there. Instead of protecting the Susquehannock, who had been invited to move to the Potomac River, Maryland's colonial officials joined with the Virginians in the assault on the fort.

In a truce during the assault, Susquehannock emissaries were murdered without cause. The six-week siege of the fort ended when the Susquehannock escaped. They ceased any pretense of being allies with the Maryland and Virginia colonies. Instead, the Susquehannock retaliated against their harsh treatment by raiding isolated Virginia settlements along the Fall Line, which was the edge of colonial occupation at the time.7

Gov. William Berkeley failed to respond to demands for military protection, so the colonists living near the Fall Line initiated what became Bacon's Rebellion in 1676. Gov. Berkeley was forced to flee to the Eastern Shore, the colonial capital of Jamestown was burned to the ground, and homes of the gentry were plundered by the rebels. For the first time, British officials sent two regiments of the army to Virginia to restore the official government and to protect the colonists.8

The Virginians and the British did not seek out and fight the Susquehannocks, who were still perceived as powerful warriors. During Bacon's Rebellion, the rebel forces attacked peaceful Native American tribes allied with the Virginia government, including the Rappahannock, Pamunkey and Occaneechee.

The Iroquois took advantage of the situation. They quickly conquered the scattered Susquehannocks, once their old enemies were left without a fortified base and forced to wander through the Piedmont:9

- Wolves to the English, the Susquehanna were sheep to the ravaging Iroquois. Fled from the last of their famous fortresses and so deprived of their cultural as well as heir military center, dispersed in small bands in the wilderness, the Susquehanna's station was now like that of the Huron, the Erie, the Petun, and the Neutral Nations, prior victims of the Five Nations.

- During the winter of 1675-76, and in those that followed it, the Susquehanna were found by the western Iroquois "behind Virginia" and ceased to exist as a people. By consumption, by enslavement, by settlement, by adoption, over the next four years the Susquehanna became Iroquois.

The last known town of the Susquehannocks is located in York County, Pennsylvania. What is now Native Lands County Park was once a town surrounded by a palisade with 16 ninety-foot longhouses. Each longhouse provided shelter for about 50 people.10

the last known town of the Susquehannocks is now Native Lands County Park (red X)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Susquehannocks lost their independence and agreed to be subordinate to the Iroquois in a 1677 treaty negotiated by New York Governor Andros at Shackamaxon.11

The Piscataway survived the attempts of the Susquehannocks and Five Nations to displace them, and/or make them subordinate, by becoming allies with Maryland's forces against the Susquehannocks. Governor Calvert relocated the Piscataway in 1680 from their old base on Piscataway Creek to Zekiah Swamp, which the governor controlled personally as a proprietary manor in Charles County.12

Links

- Documenting the American South (University of North Carolina)

- First Nations Issues of Consequence

- National Park Service

- Prince William Network/Virginia Department of Education

- The Nanticoke Community of Delaware (by Frank G. Speck, 1915)

- Virginia Foundation for the Humanities

- Woodland Indian Educational Programs

four Susquehannock (Minqua) towns on the Susquehannock River were documented by the Dutch in 1616

Source: New York Public Library, Map of New Netherland (by Schipper Cornelis Hendricksen, 1616)

References

1. Francis Jennings, "Glory, Death, and Transfiguration: The Susquehannock Indians in the Seventeenth Century," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 112 Number 1 (February 15, 1968), pp.16-17, http://www.jstor.org/stable/986100; "Centuries-old Susquehanna petroglyphs give history a personal touch," Chesapeake Bay Program, November 5, 2020, https://www.chesapeakebay.net/news/blog/centuries_old_susquehanna_petroglyphs_give_history_a_personal_touch (last checked November 13, 2020)

2. "Mahican History," First Nations Histories, July 3, 1997, http://www.dickshovel.com/Mahican.html (last checked August 9, 2015)

3. James H. Merrell, "Cultural Continuity among the Piscataway Indians of Colonial Maryland," The William and Mary Quarterly, Volume 36 Number 4 (October, 1979), pp.556-557, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1925183 (last checked August 10, 2015)

4. Stephen Saunders Webb, 1676 The End of American Independence, Syracuse University Press, 1995, pp.290-91; "The Dutch Surrender New Netherland, 350 Years Ago," History.com, September 8, 2014, http://www.history.com/news/the-dutch-surrender-new-netherland-350-years-ago; Alan Gallay, Colonial Wars of North America, 1512-1763: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, 2015, PT1060, ; Jeffrey Glover, Paper Sovereigns: Anglo-Native Treaties and the Law of Nations, 1604-1664, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014, p.182, https://books.google.com/books?id=KEZBAwAAQBAJ; Alex J. Flick, Skylar A. Bauer, Scott M. Strickland, D. Brad Hatch, Julia A. King. "...a place now known unto them:" The Search for Zekiah Fort, St. Mary's College of Maryland, 2012, pp.11-14, https://www.academia.edu/2484589/_A_Place_Now_Known_Unto_Them_The_Search_for_Zekiah_Fort_by_Alex_J._Flick_Skylar_A._Bauer_Scott_M._Strickland_D._Brad_Hatch_and_Julia_A._King; Charles L. Heath, "Catawba Militarism: Ethnohistorical And Archaeological Overviews," North Carolina Archaeology, Volume 53 (2004), pp.82-83, https://archaeology.sites.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/187/2017/08/Catawba-Militarism.-Ethnohistorical-and-Archaeological-Overviews-2004-Heath.pdf (last checked August 5, 2025)

5. Alex J. Flick, Skylar A. Bauer, Scott M. Strickland, D. Brad Hatch, Julia A. King. "...a place now known unto them:" The Search for Zekiah Fort, St. Mary's College of Maryland, 2012, p.19, https://www.academia.edu/2484589/_A_Place_Now_Known_Unto_Them_The_Search_for_Zekiah_Fort_by_Alex_J._Flick_Skylar_A._Bauer_Scott_M._Strickland_D._Brad_Hatch_and_Julia_A._King (last checked August 8, 2015)

6. Alex J. Flick, Skylar A. Bauer, Scott M. Strickland, D. Brad Hatch, Julia A. King. "...a place now known unto them:" The Search for Zekiah Fort, St. Mary's College of Maryland, 2012, p.1, https://www.academia.edu/2484589/_A_Place_Now_Known_Unto_Them_The_Search_for_Zekiah_Fort_by_Alex_J._Flick_Skylar_A._Bauer_Scott_M._Strickland_D._Brad_Hatch_and_Julia_A._King (last checked August 8, 2015)

7. Alex J. Flick, Skylar A. Bauer, Scott M. Strickland, D. Brad Hatch, Julia A. King. "...a place now known unto them:" The Search for Zekiah Fort, St. Mary's College of Maryland, 2012, pp.19-20, https://www.academia.edu/2484589/_A_Place_Now_Known_Unto_Them_The_Search_for_Zekiah_Fort_by_Alex_J._Flick_Skylar_A._Bauer_Scott_M._Strickland_D._Brad_Hatch_and_Julia_A._King (last checked August 8, 2015)

8. James D. Rice, Tales from a Revolution: Bacon's Rebellion and the Transformation of Early America, Oxford University Press, 2013. pp.18-23, https://books.google.com/books?id=loVSAwAAQBAJ (last checked August 5, 2015)

9. Stephen Saunders Webb, 1676 The End of American Independence, Syracuse University Press, 1995, p.292

10. "Native Lands Park," Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/cajo/planyourvisit/native-lands-park.htm (last checked March 23, 2019)

11. Francis Jennings, "Glory, Death, and Transfiguration: The Susquehannock Indians in the Seventeenth Century," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 112 Number 1 (February 15, 1968), http://www.jstor.org/stable/986100 (last checked August 10, 2015)

12. Alex J. Flick, Skylar A. Bauer, Scott M. Strickland, D. Brad Hatch, Julia A. King. "...a place now known unto them:" The Search for Zekiah Fort, St. Mary's College of Maryland, 2012, p.1, https://www.academia.edu/2484589/_A_Place_Now_Known_Unto_Them_The_Search_for_Zekiah_Fort_by_Alex_J._Flick_Skylar_A._Bauer_Scott_M._Strickland_D._Brad_Hatch_and_Julia_A._King (last checked August 10, 2015)

the Susquehannock controlled central Pennsylvania when English colonists arrived

Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, A new map of the north parts of America claimed by France (1720)

"Indians" of Virginia - the Real First Families of Virginia

Virginia Places