the Mattaponi Reservation is upstream from the confluence of the Pamunkey and Mattaponi rivers (the headwaters of the York River)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the Mattaponi Reservation is upstream from the confluence of the Pamunkey and Mattaponi rivers (the headwaters of the York River)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Mattaponi were one of the original six tribes whose control was inherited by Powhatan, within the boundaries of his paramount chiefdom territory known as Tsenacommacah.

When the English colonists arrived in 1607, the Mattaponi lived at the headwaters of what became known as the York River near the confluence of the Pamunkey and Mattaponi rivers. The site was relatively far away from the western border of Tsenacommacah on the Fall Line; there was low risk of Monacan and Massawomeck raids. The threat, as it turned out, came from the east as the English expanded from Jamestown.

After the 1622 uprising and the negotiations that ended the Second Anglo-Powhatan War, the Mattaponi retained control of their homeland. In the 1630's, the English built a wall on the Peninsula between the York and James rivers running through Middle Plantation (Williamsburg). he territory they isolated on the English side of the wall was south of the York River, not part of the Mattaponi homeland on the Middle Peninsula.

The capture and murder of Opechancanough ended the Third Anglo-Powhatan War in 1646. A peace treaty with the new paramount chief Necotowance drew tighter boundaries to separate the Native Americans from the colonists. all of the Peninsula was reserved for the English. The English promised in 1646 that the Middle Peninsula would not be colonized without notice, but the same General Assembly that approved the peace treaty used a loophole in the treaty to make provisions for settlement north of the York River:1

The Mattaponi recognized that their homeland was threatened; English settlers would move north of the York River into the Middle Peninsula when it suited them. The solution was to move north, further away from the colonists.

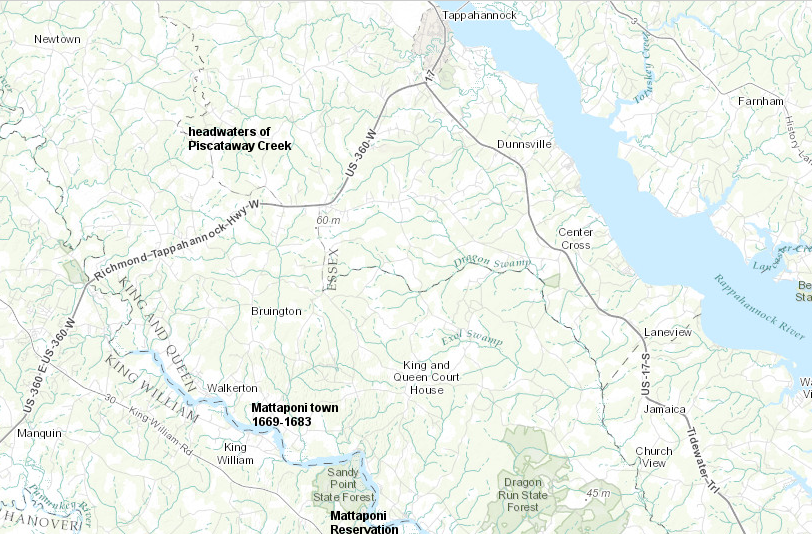

The tribe chose moved under pressure to the woodlands at the headwaters of Piscataway Creek, on the watershed divide between the Mattaponi and Rappahannock rivers. Remnants of the Chickahominy, Rappahannock, and Morattico (Moraughtacund) tribes made the same decision to migrate and joined the Mattaponi on the ridge.

The name "Mattaponi" means "people of the river. Their move to the headwaters of Piscataway Creek required abandoning easy access to food sources in tidal marshes, where the tuckahoe plant (Peltandra virginica or Arrow arum) provided starchy tubers for winter meals. However, the English were establishing farms or "quarters" staffed with indentured servants and slaves at mouths of the creeks emptying into the York and Potomac rivers. Different groups of Native Americans made the hard choice to move away from the shoreline of tidal rivers and live at a safer, but less suitable, location.

the Mattaponi moved from their traditional settlement area to the headwaters of Piscataway Creek after the Third Anglo-Powhatan War ended in 1646

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Old Rappahannock County made a treaty with the Mattaponi in 1656. The county authorized hunting by the Mattaponi on lands owned by colonists, except for fenced-in plantation lands. The tribe agreed to pay damages whenever English livestock were killed.

In 1658, the General Assembly authorized the Mattaponi's return to their traditional lands at the mouth of the Mattaponi River. The legislature, which was under the authority of the Commonwealth government of England after the Puritans had won the English Civil War and executed King Charles I, passed a law creating a reservation of land for the Mattaponi at their ancestral home.

Two years earlier, the Pamunkey chief Totopotomoy had led a force of Native Americans together with the colonists to fight against the Rickohockans. Totopotomoy and many of his warriors had been killed in the Battle of Bloody Run after Colonel Edward Hill of Shirley Plantation mismanaged the expedition to the Fall Line of the James River. The General Assembly may have recognized the relative contribution of Totopotomoy people and desired to appease them.2

Bloody Run is between Church and Chimborazo hills

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the city of Richmond, Virginia (1864)

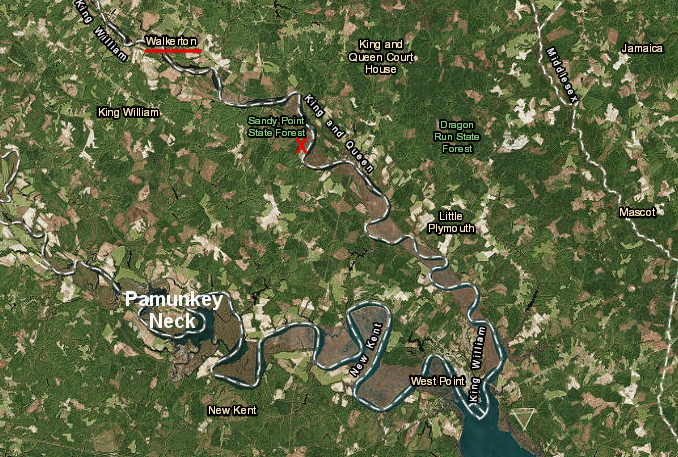

The Mattaponi had returned back to the Mattaponi River and its wetlands by 1669. They built a new town downstream of modern Walkerton. The Chickahominy built a town nearby, creating an island of "Indian country" surrounded by colonists' farms. The Rappahannock and Morattico stayed on the ridge above Piscataway Creek until 1684, when local officials moved the Rappahannock (perhaps including the Marattico by then) to Portobago.

the Mattaponi returned to the Mattaponi River by 1669, settling downstream of modern Walkerton (X marks modern reservation site)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

During Bacon's Rebellion in 1676, the Mattaponi were attacked by the rebels. Chief Yau-na-hah was killed, and the tribe retreated into Dragon Swamp at the headwaters of the Piankatank River. Under leadership of Yau-na-hah's son Mahayough, they returned to their town on the Mattaponi River at the end of the rebellion; the move into Dragon Run was a temporary escape, not a permanent relocation. The 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation created an 18,000-acre exclusive Native American zone around the settlement on Pamunkey Neck.3

The 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation was signed by the English and various "tributary" tribes in Virginia, but had no effect on rival groups outside of Virginia. In 1683, the Iroquoian-speaking Seneca raided south from New York and pushed the Mattaponi out of their town again. The Mattaponi and next-door Chickahominy relocated to the Pamunkey Neck area, briefly living with the Pamunkey tribe before returning back to the Mattaponi River.

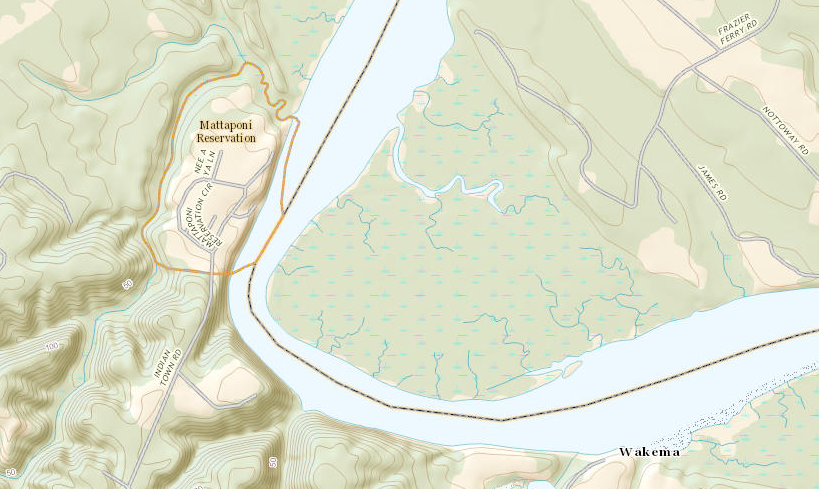

For the next two centuries, Virginia and local officials dealt with the Mattaponi and Pamunkey jointly. The tribe re-established its separate identity in 1894 when it negotiated creation of a separate reservation at the end of Indian Town Road between Indian Town Swamp and the Mattaponi River.4

the Mattaponi Reservation includes prime territory surrounded by food-rich marshes and uplands, where anadromous fish can be caught in spawning runs

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Virginia General Assembly established a separate Mattaponi Reservation in 1894. The legislature also appointed white trustees to handle legal matters, comparable to the trustees appointed for the Pamunkey since 1676.

The division of the old Pamunkey Reservation allocated to the Mattaponi tribe a 150-acre property on the Mattaponi River, eight miles away from Pamunkey Neck. In contrast, the Pamunkey Reservation consisted of 1,200 acres.

Of the 18,000 acre reservation established in the 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation, the Mattaponi now occupy 1% and the Pamunkey occupy 7%. The rest of the land has been transferred out of Native American tribal control.5

The 1894 tribal split occurred when the Pamunkey were asserting their historical status, conducting outreach into the white community. The Pamunkey began appearing in buckskin clothes with turkey feather headdresses. They offered public dances and a play about Pocahontas saving John Smith's life, and participated at the Chicago Worlds Fair in 1893. The less-assertive, more-traditional Mattaponi chose to re-establish their own separate identity.6

During the days of Jim Crow, the Mattaponi operated their own separate school on the reservation. They also started a fish hatchery there.

The Pamunkey tribe received Federal recognition through the administrative process of the Department of the Interior in 2015, and six other tribes were recognized by legislative action in the 2018 Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act. The Mattaponi did not seek to be recognized through the legislative process (the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act) and have not pushed forward a proposal to be recognized through the administrative process managed by the US Department of the Interior. The Mattaponi are still are not Federally recognized.

Today, about 70 of the 380 members of the Mattaponi tribe live on the reservation. The reservation is held in trust by the state of Virginia. The reservation is not held in trust by the Federal government, which was created long after colonists set aside land for the Mattaponi. Absent Federal recognition and without the reservation being held in trust by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Mattaponi are not entitled under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act to offer gaming.

In 2020, King William County assessed the 125 acres of the Mattaponi Indian Reservation at that time as worth $818,000, plus $641,000 for improvements.7

The first boundary change to the reservation since it was established in 1894 occurred in 2019. The Mattaponi purchased an additional 100 acres adjacent to the reservation, and Governor Ralph Northam signed an agreement to add that land to the Mattaponi Indian Reservation. Funding came from the mitigation payment for the Surry-Skiffes Creek Transmission Line Project, which affected historic vistas of the James River downstream from Jamestown.

The Secretary of the Commonwealth, the state official assigned as chief liaison with the Virginia tribes, commented:8

Some tribal conflicts are resolved in Virginia courts. In 2021, Mattaponi women complained that the ruling council excluded them and no council elections had been held since the 1970's. They brought a petition to Chief Mark Custalow's house. He responded by going to the magistrate for the King William General District Court and charged 13 people with the misdemeanor of trespassing and assault by mob.

The county government was also involved when recordings of three meetings of the Mattaponi Tribal Council appeared on YouTube. The Commonwealth's Attorney in King William County sent a search warrant to Google, seeking to identify who uploaded the recordings because they might have been made illegally. After determining that the site posting the recordings, Mattaponi Voice, was an independent, online publication, the Commonwealth's Attorney withdrew the search warrant because publication was legal even if the recordings had been made without required authorization.

The two cases demonstrated that the tribe relied upon the Commonwealth of Virginia, rather than a tribal court, to resolve legal issues.9

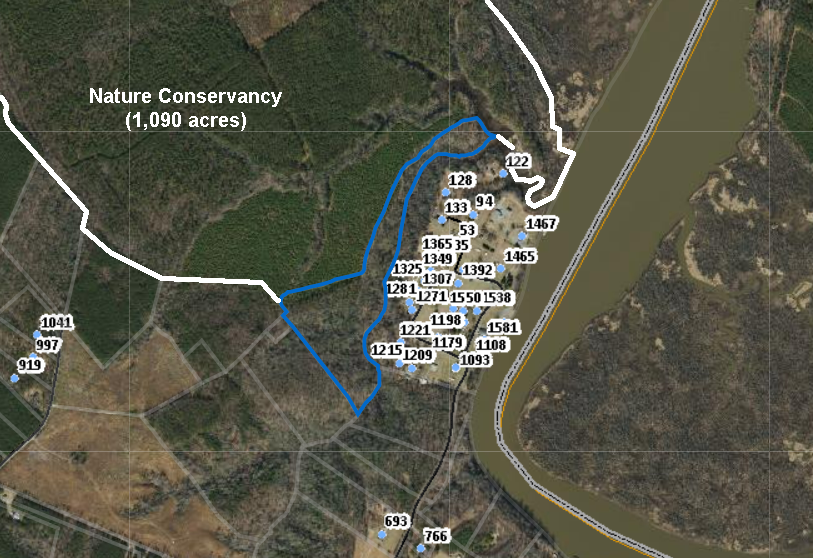

the 125-acres of land in the Mattaponi Indian Reservation was assessed by King William County at $818,000 in 2020

Source: King William County

the Mattaponi own an additional 27 acres (blue boundary) west of the 125 acres of reservation land where houses have been built

Source: King William County, GIS Mapping System

the Mattaponi and Pamunkey reservations are eight miles from each other

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

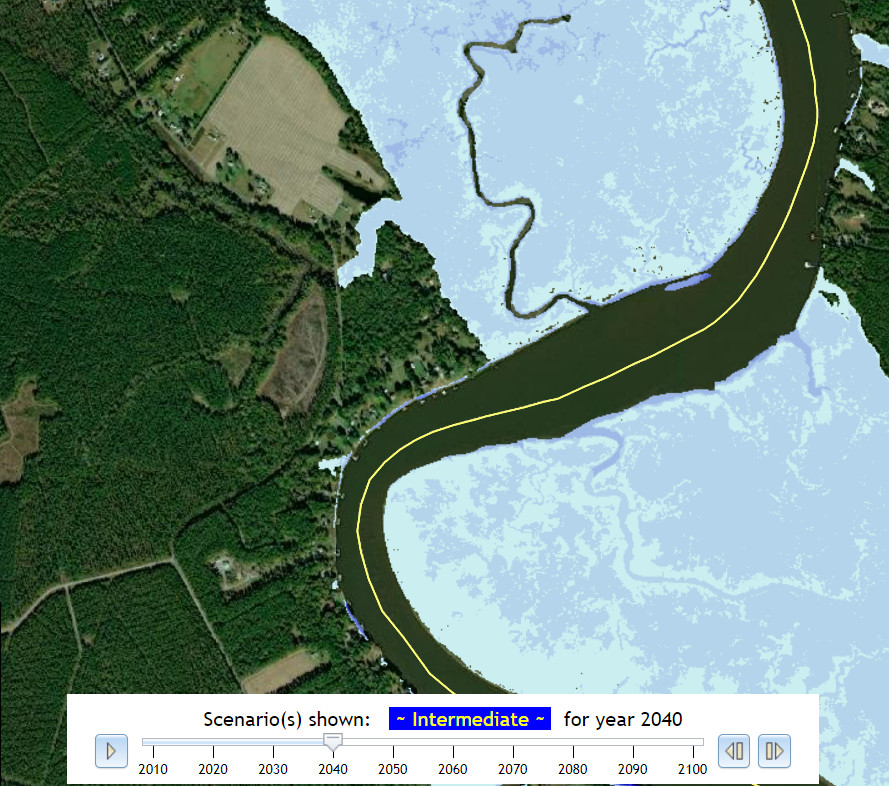

sea level rise could drown the marshes near the Mattaponi Reservation by 2040, but the current houses would still be above the flood plain

Source: Commonwealth Center for Recurrent Flooding Resiliency, Sea Level Rise Projection

directions to Mattaponi Reservation in King William County

Custalow headstones are common in the graveyard of Mattaponi Indian Baptist Church on Mattaponi Reservation in King William County