The Three Linguistic Groups of Colonial Virginia

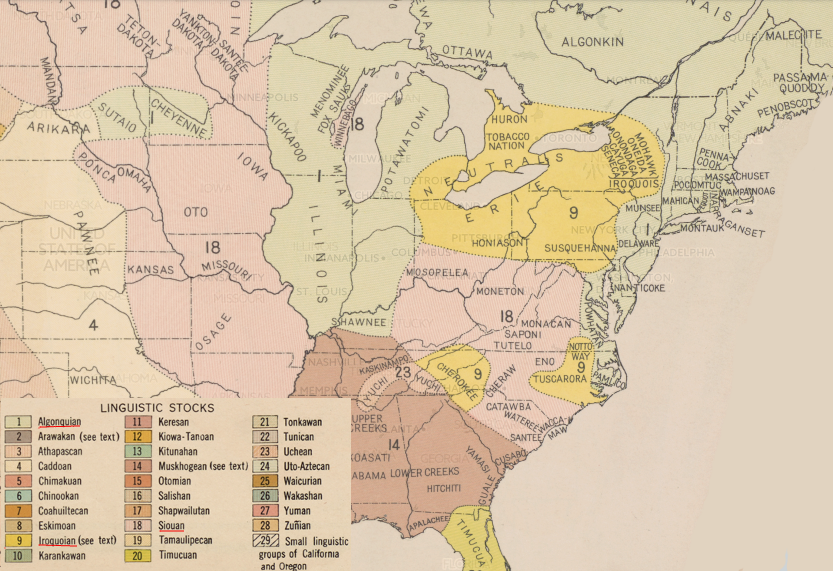

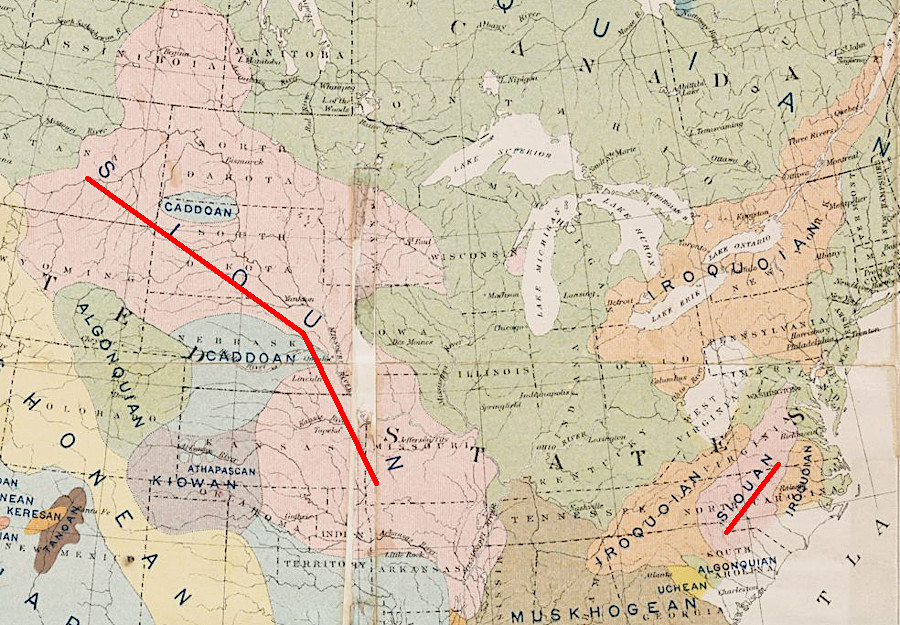

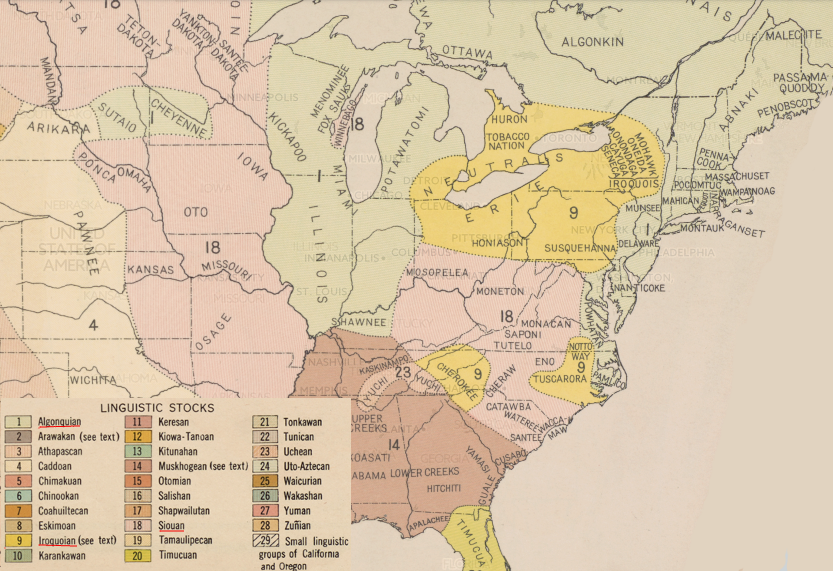

when the English arrived in 1607, Native Americans used just three of the 28 major linguistic groups common in North America

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Indian Tribes and Linguistic Stocks, 1650 (Plate 33, digitized by University of Richmond)

The Europeans who arrived in Virginia discovered numerous tribes with distinct identities, but the different tribes used only three major linguistic groups: Algonquian, Siouan, and Iroquoian.

At the time of first contact in the 1500's, Native Americans in the Western Hemisphere spoke 800-1,000 different languages. Based on similarities between them, there were 25-30 "families" of languages.

Linguists compare words for common terms in different languages, such as "child," to identify original source languages and how they have differentiated over time. The technique offers a clue regarding how long people have been in the Western Hemisphere.

One thesis is that First American (Amerind), Eskimo-Aleut, and Na-Dene are the three major groups of languages in the Western Hemisphere, and those three groups reflect three migrations via Beringia at different times. The time required for the evolution of language differences suggests people have lived in the Western Hemisphere for 50,000 years.

However, genetic evidence suggests that language differences are not based on initial "waves" of migration from Beringea. It is more likely that more than three groups moved out of Beringea into North America, and movements were not limited to three major migrations of people using separate languages.

Perhaps the first people arrived more than 50,000 years ago, but none survived and the first languages brought to North America disappeared with them. It is possible that there were additional migrations by people speaking languages not associated with First American (Amerind), Eskimo-Aleut, or Na-Dene, but languages used by those migrants completely died out.1

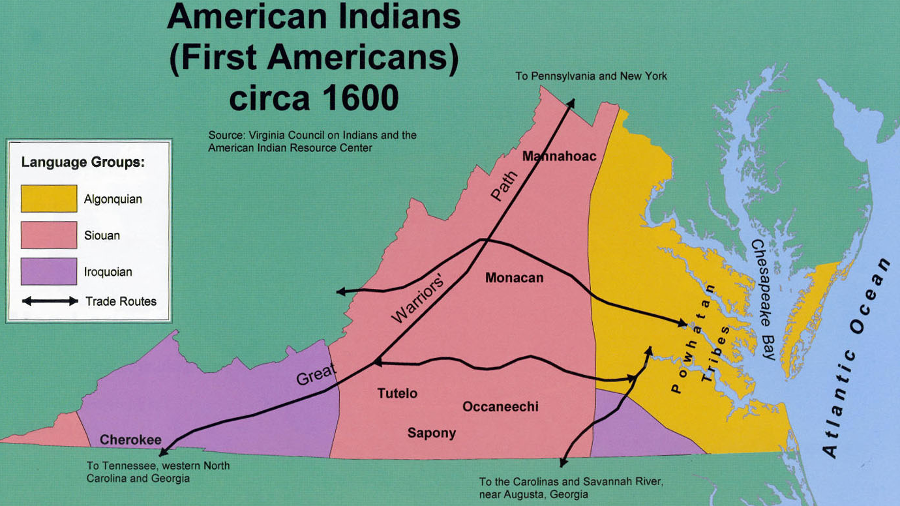

When the English arrived in the 1600's, Native Americans in Virginia spoke languages associated with three major groups. Different tribes spoke different variants of Algonquian, Siouan, or Iroquoian languages.

In contrast, there were 22 linguistic groups and 135 regional dialects spoken within California, where the Native Americans maintained a hunting-gathering lifestyle. In contrast to the settled agricultural tribes in Virginia, the groups on the West Coast lived in fragmented, separate spaces and their languages did not coalesce.2

Tidewater Virginia tribes, including the 30+ tribes controlled by Powhatan in his paramount chiefdom of Tsenacommacah, spoke some version of an Algonquian language. Powhatan was born in an Algonquian-speaking town on the Fall Line of what was later named the James River. He expanded his original control over six tribes towards the east, north, and south, but gained no control towards the west. Powhatan's enemies on the west all spoke Siouan languages, suggesting they shared a common culture and perhaps common resistance against efforts by Powhatan to gain control over territory west of the Fall Line.

North of Tsenacommacah, the Dogue and other tribes associated with the Piscataway tayac also spoke an Algonquian language. Far to the west in the Ohio River Valley, the Shawnee also communicated in Algonquian languages.

Algonquian-speaking groups (in red) were common in North America, and dominated Tidewater Virginia

Source: Wikipedia, Algic languages

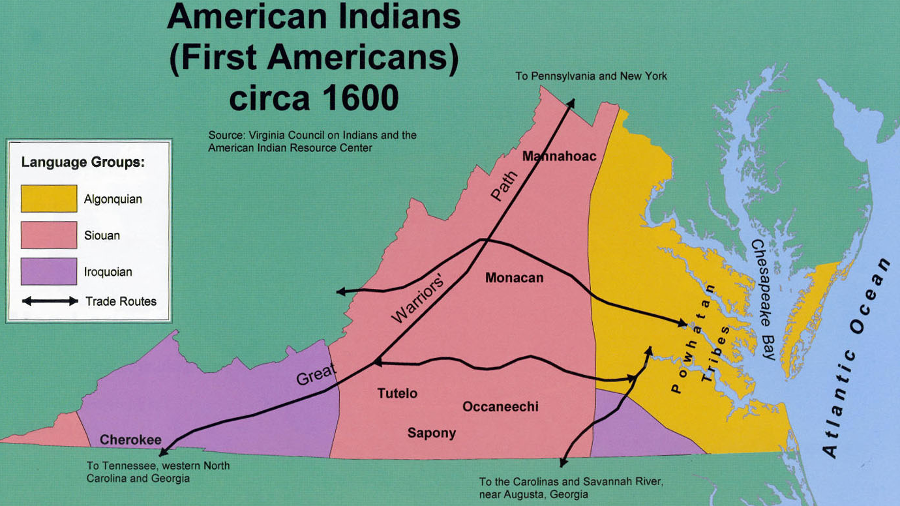

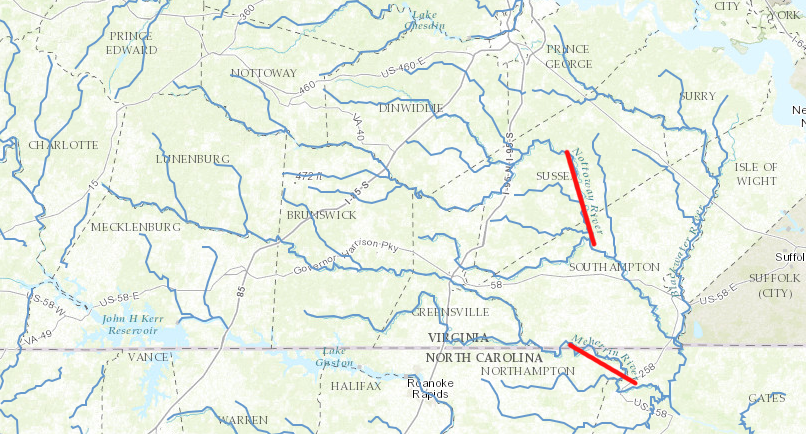

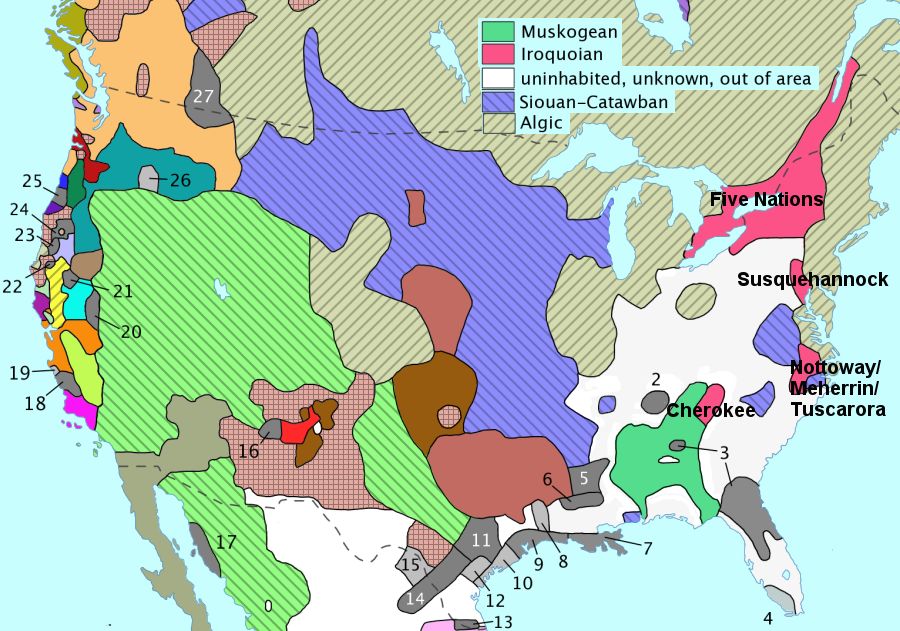

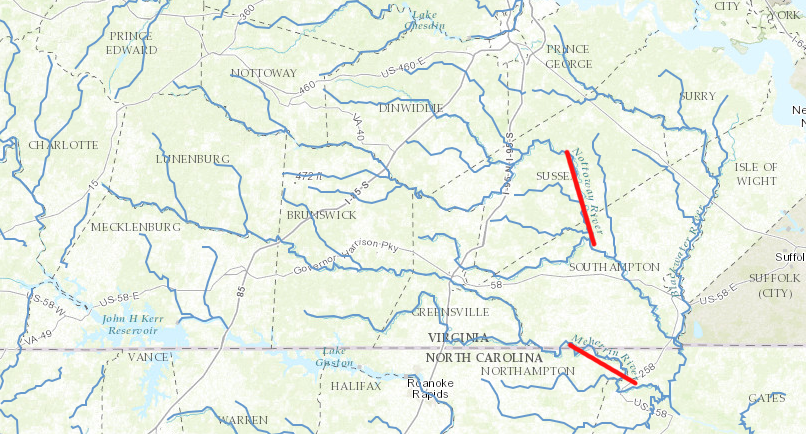

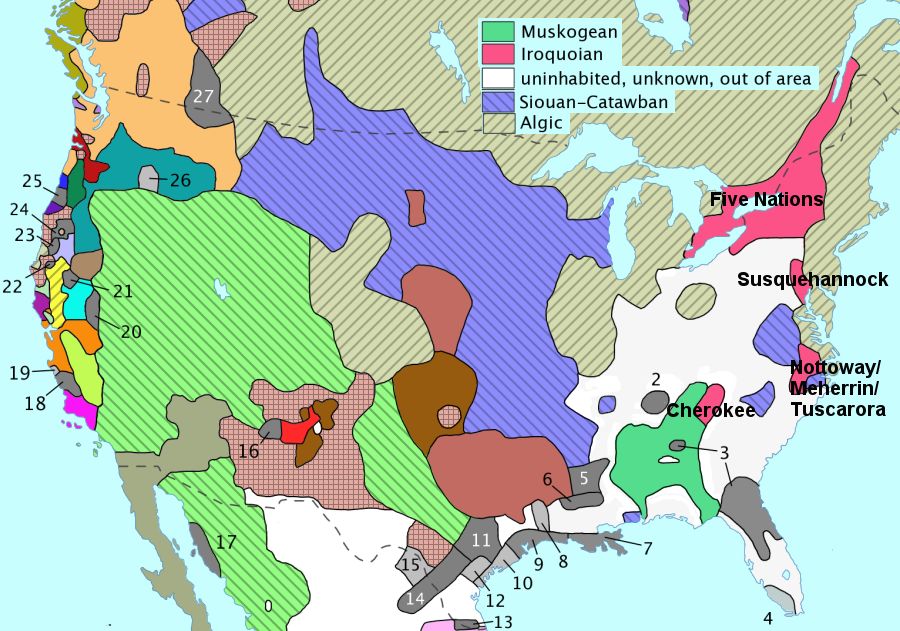

South of Tsenacommacah, the Nottoway, Meherrin, and Tuscarora also lived in Tidewater and on the eastern edge of the Piedmont. Those three tribes spoke Iroquoian languages. To their north, the closest other Iroquoian-speaking groups were the Susquehannock living at the northern edge of the Chesapeake Bay, the Haudenosaunee (Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, Seneca, also known as the Five Nations or Iroquois Confederacy) living south of the St. Lawrence River, and the Huron living north of Lake Ontario.

Iroquoian speakers lived south of Powhatan's paramount chiefdom, and the Cherokee in the Tennessee River watershed shared the same language group

Source: An Atlas of Virginia, American Indians (First Americans) circa 1600 (Map 26, produced by the Virginia Geographic Alliance)

There were numerous Algonquian-speaking tribes living between the Nottoway/Meherrin/Tuscarora and those other Iroquoian-speaking groups to the north. A trader going north from the Nottoway River would have to use Algonquian words. Once the trader reached the James River, they were within Tsenacommacah. In Powhatan's paramount chiefdom, all the tribes spoke an Algonquian language.

If the trader kept going north, he would leave Tsenacommacah but still need to know the Algonquian words. He would have to cross the Potomac River and go further north, up to the modern Pennsylvania border, before reaching the Iroquoian-speaking Susquehannock. North of Tsenacommacah, between the Potomac and the Susquehannock, the territory was still occupied by Algonquian-speaking tribes associated with the Piscataway tayac.

Once reaching the Susquehannock, translation skills were still necessary. Even though the root base of the Nottoway/Meherrin/Tuscarora languages and the Susquehannock were common, the trader would still have to do business in the distinctive languages of the northern Iroquoian-speaking groups.

A Nottoway/Meherrin/Tuscarora trader seeking to exchange Atlantic Ocean shells for copper from the west faced a similar challenge. The Iroquoian-speaking Cherokee lived west of the Blue Ridge, but they were isolated from the Iroquoian-speaking tribes in Tidewater by Siouan-speaking tribes.

When the English landed at Jamestown in 1607, the Siouan-speaking Catawba, Occaneechi, Saponi and Tutelo occupied the southern Piedmont in North Carolina and Virginia. Siouan-speaking Monacan and Manahoac controlled the northern Piedmont, north of the James River. Nottoway/Meherrin/Tuscarora traders were isolated from other Iroquoian-speaking groups. They had to pass through territory occupied by people speaking foreign languages before reaching another group whose words/grammar were also Iroquoian.

the Nottoway and Meherrin rivers indicate the homelands of those two Iroquoian-speaking groups

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The reason for the disjunct territories, and why Iroquoian-speaking, Siouan-speaking, and Algonquian-speaking groups were not all located next to each other, is not clear.

How the Native Americans communicated when they reached North America 15,000 years ago is unknown. It is not likely that the languages used during the time Paleo-Indians made Clovis spear points were the same languages spoken when Europeans arrived. Native American cultures changed dramatically over the 15,000 years, as did the European cultures.

Paleo-Indian populations may have been so mobile that everyone used the same signals to coordinate hunting, cooking, and living together. The roots of the languages used when Europeans arrived may date back into the Archaic Period, to a time when groups of hunter-gatherers focused on living in a particular area.

Such groups learned through seasonal rounds when fruits and nuts ripened, and where to go in order to maximize the harvest. The hunter-gatherers learned the migration routes of wild animals and the times when fish were most abundant in streams. Competition for good sites for collecting food would have led to defined, territorial boundaries between different groups. Boundaries may have fluctuated as different groups fought for territory, but during the Archaic Period different bands of hunter-gatherers established distinct cultures.

One factor could have been the domestication of the first plants during the Archaic Period, as the Eastern Agricultural Complex developed. As the benefits of early agriculture became clear, the desire to control particular river bottoms would have increased. The opposite may also be true - the desire to control particular territory (perhaps to stay connected to the graves of ancestors) drove the adoption of agriculture, because crops provided a reliable food supply to people choosing to stay in one place. Within a specific territory, common cultural patterns would have developed and a common language would have evolved.

One group developed the proto-Iroquoian language as a common form of communication. At other locations, separate groups developed early versions of Siouan, Algonquian, Muskohegan, and other languages. Territorial boundaries limited interaction between different groups, and different languages may reflect ancient competition and ancient homeland boundaries.

If that hypothesis about the formation of language is true, then the English who arrived in 1607 should have found all Algonquian-speaking groups living in one homeland, all Iroquoian-speaking groups living in a second area, and all Siouan-speaking groups living in a third territory. However, the Europeans encountered a different pattern, with tribes speaking the same languages separated by tribes speaking different languages.

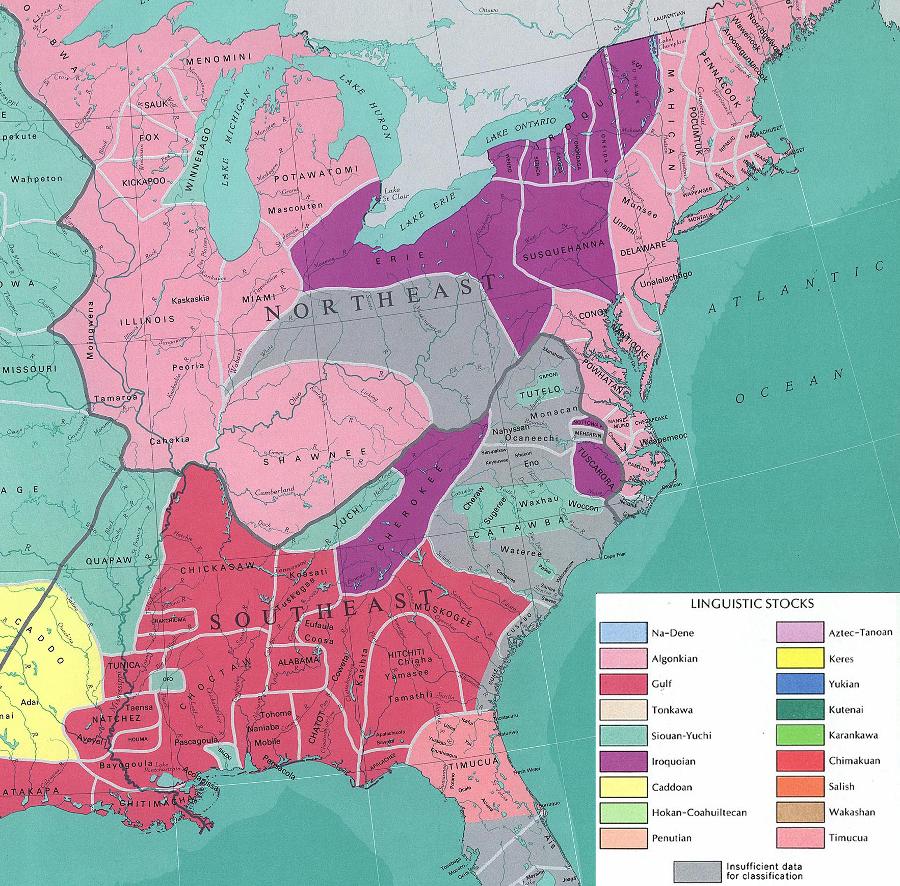

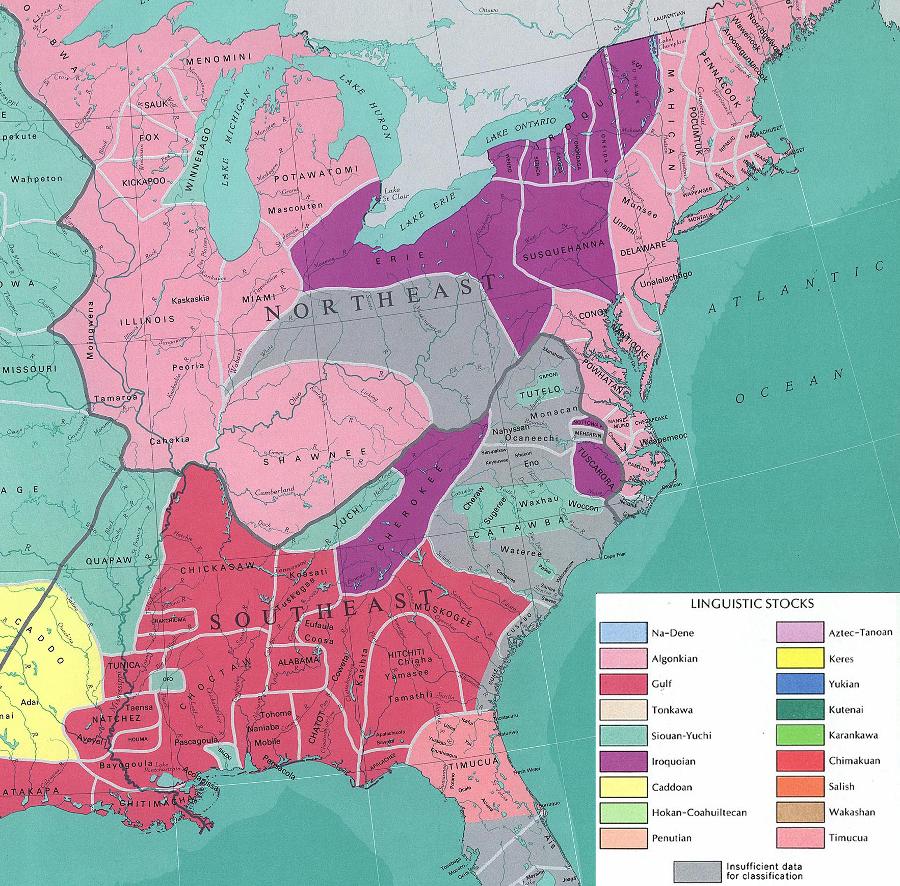

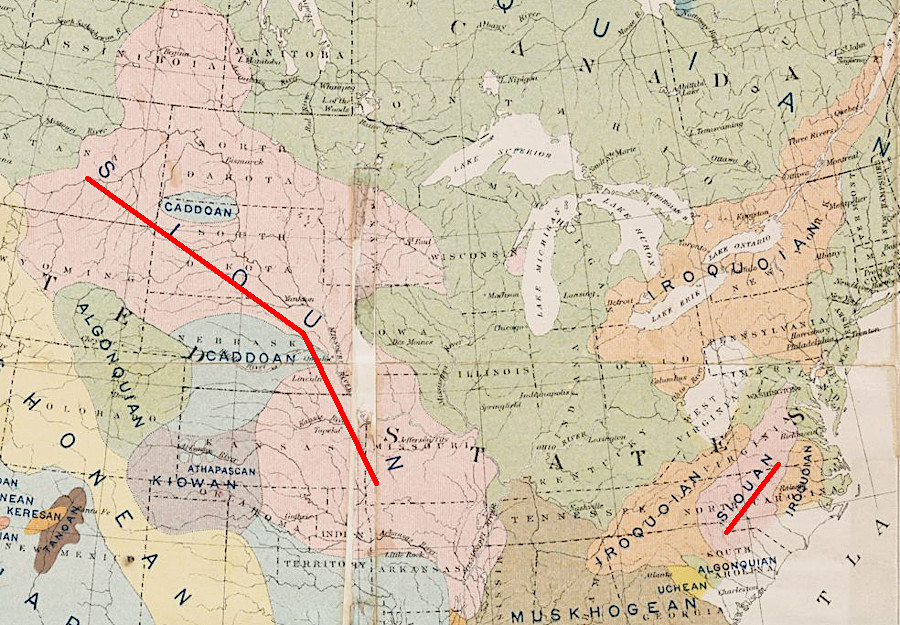

languages that may have developed in specific homelands were carried to new locations by migrations of different Native American groups

Source: National Atlas, Indian Tribes, Cultures, and Languages (posted online by University of Texas, Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection)

To create such a pattern, an extra step is required - always assuming related languages developed in one common area initially, and were not invented in parallel by different groups in separate places. To have the fragmented pattern of languages and territory discovered by the Europeans in the 1500's and 1600's, some Iroquoian-speaking, Siouan-speaking, and Algonquian-speaking groups must have migrated away from that central place where their languages first evolved.

Those migrants must have carried common words and grammar from their homeland. Some migrants ended up in Tidewater, while others established control over territory in the Piedmont or the Blue Ridge. All retained key elements of the common language they had shared.

The cultural component of language was never frozen. It changed as people migrated, and once they settled in a new location. Though the way people talked gradually shifted as different groups became established in different areas, language did not diverge as much as pottery styles or stories about the creation of earth. Common ancestry can be traced through common patterns of speech.

The migrants that had started with a common language did not always stay allies, despite their shared heritage. For example, the colonists discovered in the 1700's that the Cherokee and the five tribes of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) in New York constantly raided each other's towns as well as towns of their Siouan-speaking neighbors. The Haudenosaunee exerted as much effort to gain dominant status over the Iroquoian-speaking Susquehannock as over the Algonquian-speaking Delaware.

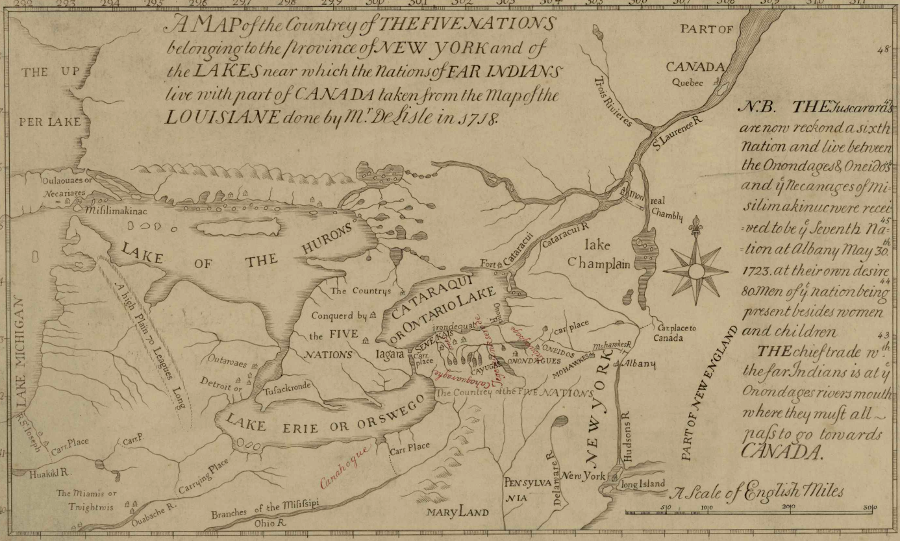

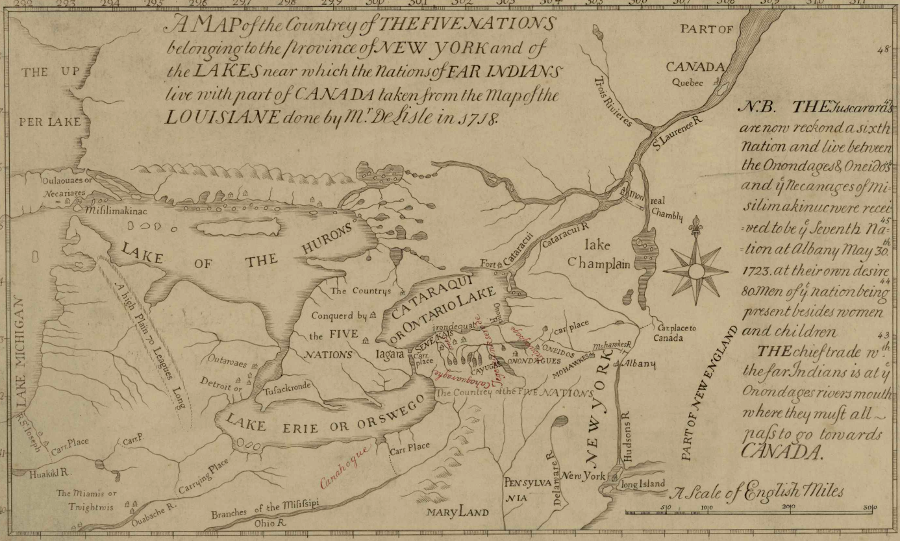

the Tuscarora moved from Tidewater to New York after losing a war with North Carolina in 1711-15

Source: University of Pittsburgh, Map of the Country of The Five Nations (1730)

The hypothesis that language evolved as agriculture was adopted, and that language was retained as groups dispersed, does not answer the question "where was the original homeland" of a group.

For the Cherokee, one hypothesis is that the language goes back to the first stages of domesticating plants. Linguists suggest that one group speaking proto-Iroquoian split off 3,500 years ago. Cherokee is the one Southern Iroquoian language that developed after the split and has survived. The other proto-Iroquoian speakers stayed together longer, and the Tuscarora, Meherrin, Nottoway, Susquehannock, Haudenosaunee, and Huron all descend from the Northern Iroquoian speakers.

The differences between the languages spoken by the Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, and Seneca emerged about 1,500 years ago, two millennia after the Southern Iroquois split. The period of separation of different tribes can be related to the differences in their languages. The Susquehannock language is closest to that of the Onondaga, suggesting they were the last two groups to separate. The Cayuga language is the most distinct from the other four nations that formed the Iroquois Confederacy, suggesting they were isolated from the other tribes for a substantial time.

It appears that an Iroquoian-speaking culture developed in the northeast, with a homeland in New York near the St. Lawrence River, as much as 3,500 years ago. Some of them migrated south far enough to occupy the upper Tennessee River Valley. A later migration, within the last 1,500 years, brought people speaking Northern Iroquoian languages into Virginia east of the Blue Ridge.

An alternative hypothesis proposes that the proto-Iroquoian culture developed in Southern Appalachia. According to the southern hypothesis, the Cherokee evolved in-situ. After developing a familiarity with raising corn, a group then migrated to the northeast and introduced agriculture in the St. Lawrence Valley.

One weakness in that theory is that Iroquoian pottery in the St. Lawrence River lowlands pre-dates the introduction of corn. A migration of Iroquoian-speakers from the south may have brought a new group of farmers with a new crop to the northeast, but the Iroquois were already there. They could have learned how to grow corn via trade with Native Americans in the Mississippi River and Ohio River valleys, and diffusion of culture rather than migration of people could explain the change in agricultural practices.3

Even when the Iroquoian-speaking culture was dominant across Virginia, the Cherokee remained a separate society and retained a distinct Southern Iroquoian language. The Tuscarora were physically close to the Cherokee, but the Northern Iroquoian and Southern Iroquoian languages remained significantly different.

A later migration brought Algonquian-speaking groups south from New England. The proto-Algonquian language emerged around 1200 BCE. The culture developed in the forests north of the Great Lakes to Maritime Canada, north of the homeland of the proto-Iroquois in New York.

They occupied much of Tidewater east of the Fall Line, south to the barrier islands of North Carolina. The Algonquian-speaking immigrants killed, displaced, or absorbed whatever Iroquoian-speaking groups were living in Tidewater, except for the occupants who developed into the Susquehannock, Tuscarora, Meherrin, and Nottoway.

The Algonquian-speaking group later evolved into the historic tribes in Tidewater that the English colonists encountered. Sir Walter Ralegh's group that arrived in 1584, and the "Lost Colony" of 1587, met Algonquian-speaking residents on the barrier islands and the North Carolina coastline.

After the arrival of the Algonquian-speaking immigrants, the territories of the resident Iroquoian-speaking cultures was divided. The Nottoway/Meherrin/Tuscarora ended up separated from the Susquehannock and the Haudenosaunee, as well as from the Cherokee.

Iroquoian-speaking groups - Cherokee, Nottoway/Meherrin/Tuscarora, Susquehannock, and Haudenosaunee - were isolated from each other when Europeans reached North America

Source: Wikipedia, Iroquoian languages

At some point, the Siouan-speaking tribes moved into the Piedmont and valleys west of the Blue Ridge, pushing down to the New River.

A group of the Erie, known as the Rickahocan and later as the Westo, moved to the Fall Line of the James River in 1656. They stayed only a few years, but immediately dominated the fur trade with Virginia's colonists until moving to the Savannah River in the 1660's. The Rickahocan may have filled a space abandoned by the Monacan and Manahoac, or the Rickahocan may have forced the Monacan and Manahoac to move south and join the Catawba, Occaneechi, Saponi and Tutelo.4

The status of the Siouan-speaking tribes when the colonists arrived is not documented as well, since it took over 60 years before English explorers crossed the Blue Ridge. By the time settlers began moving into the Shenandoah Valley and pushing south towards the Tennessee River in the early 1700's, the towns of the Monacan and other Siouan-speaking tribes had been abandoned. Details of their languages were not documented well enough to trace their movements effectively.

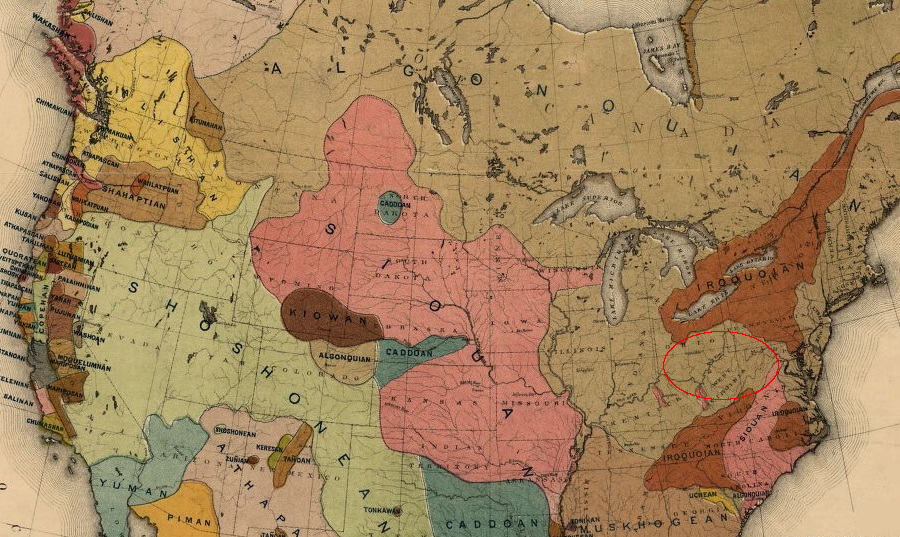

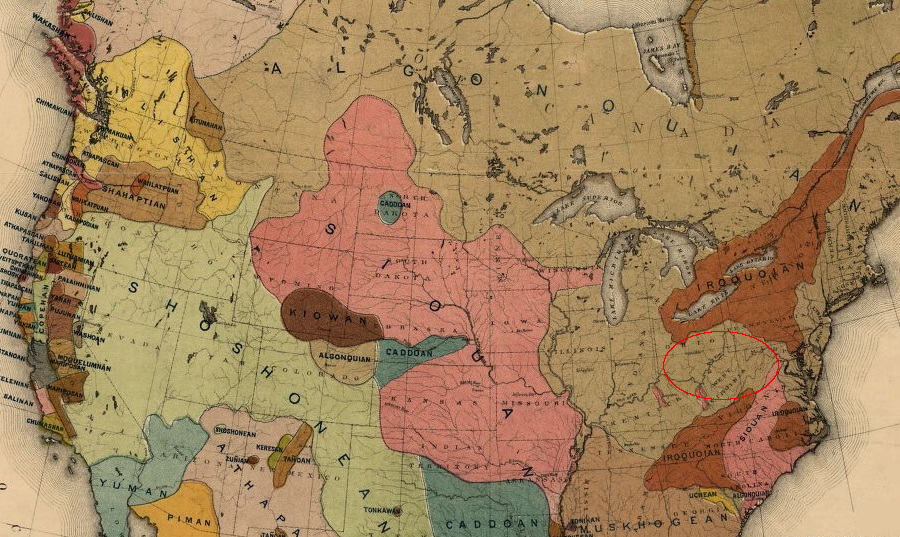

though the Shawnee spoke Algonquian, in the 1700's groups with different languages moved into the Ohio River Valley as colonists disrupted traditional settlement patterns

Source: Library of Congress, Map of linguistic stocks of American Indians (by John Wesley Powell, 1890)

The languages such as Catawba that emerged from proto-Siouan share a term for squash gourd (domesticated around 1,000 BCE) but not corn (introduced around 200 CE). That suggests one timeframe for the separation of Siouan-speaking groups. The proto-Siouan homeland may be the Ohio River Valley, or further south in the Mississippi River Valley.

The presumption is that a Siouan-speaking group migrated across the Appalachian Plateau into western Virginia, and from it evolved the Tutelo, Monacan, and other tribes. Powhatan made clear to the English that the rivalry between his Algonquian-speaking tribes and the Siouan-speaking tribes west of the Fall Line had existed for a long time.5

Algonquian (Algic)-speaking tribes migrated into the territory of Iroquoian-speaking groups and isolated the Cherokee, Nottoway/Meherrin/Tuscarora, Susquehannock, and Haudenosaunee from each other

Source: Wikipedia, Indigenous languages of the Americas

Before the colonists arrived, Native American traders doing business with different groups had to develop signs and pidgin language in order to bargain, buy, and sell. The Occaneechi maintained a trading base at a place commonly used for crossing the Roanoke River. They must have developed expertise in many of the different languages of their customers, even before Abraham Wood, William Byrd II, and others sent fur traders across the Roanoke River into the backcountry.

John Smith had a facility for communicating even before he learned Algonquian words, but was quick to place English boys with Powhatan in order to develop translators that he could understand. Most English colonists did not bother to learn the local languages, but instead focused on converting Native Americans to accept Christianity and adopt English culture.

The colonial government funded official interpreters to facilitate trade and negotiations until 1726. James Adams served as the interpreter to the Native Americans now known as the Upper Mattaponi. Even today, "Adams" is a common surname among the tribe, reflecting the influence of that interpreter's presence.6

Modern understanding of the languages used by Virginia's Native Americans is warped and incomplete. The first Virginians never developed writing, unlike cultures in Central America. Interpretation of Native American words (especially place names) is based on records from the first English settlers, later conversations with Native Americans whose culture had been altered by contact with Europeans, and in many cases from myth.

For example, the standard definition for the place name "Shenandoah" is that it means "Daughter of the Stars" - but evidence for that claim is thin. "Shenandoah" may mean "sprucy stream," or it may mean "deer," or it may mean many other things. In Saratoga County, New York, the Shenendehowa High School students call themselves the Plainsmen because they content that "Shenendehowa" means "great plains." Other stories suggest the Shenandoah Valley (and river) were named for Chief Sherando, who supposedly led an Iroquoian-speaking tribe.7

"Shenandoah" may have been Algonquian, Siouan, or Iroquoian. Shenandoah Valley historian Henry Heatwole found a solution for the origin of Shenandoah after examining various options:8

- I choose pleasing over plausible.

References

1. David Reich et al., "Reconstructing Native American population history," Nature, July 11, 2012, http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v488/n7411/full/nature11258.html; Lyle Campbell, American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America, Oxford University Press, 2000, p.98, https://books.google.com/books?id=h36tPYqAZPwC; David J. Meltzer, First Peoples in a New World: Colonizing Ice Age America, University of California Press, 2009, p.24, https://books.google.com/books?id=Rnc-bg2voI8C; "Native Languages of the Americas:

Preserving and promoting American Indian languages," http://www.native-languages.org/; Connie J. Mulligan, Emoke J.E. Szathmary, "The peopling of the Americas and the origin of the Beringian occupation model," American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Volume 162, Issue 3 (March 2017), http://10.1002/ajpa.23152 (last checked June 26, 2018)

2. Handbook of North American Indians: Languages, Government Printing Office, 1978, pp.105-109, https://books.google.com/books?id=-RnOijPup3YC (last checked July 8, 2017)

3. Andre Rolle, California: A History, Harlan Davidson Inc., 1987, p.22

4. Robbie Franklyn Ethridge, Sheri Marie Shuck-Hall, Mapping the Mississippian Shatter Zone: The Colonial Indian Slave Trade and Regional Instability in the American South, University of Nebraska Press, 2009, pp.90-91, https://books.google.com/books?id=dFNI9935DNwC; Kristalyn Shefveland, "Indian Enslavement in Virginia," Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, April 7, 2016, https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Indian_Enslavement_in_Virginia (last checked January 13, 2018)

5. Handbook of North American Indians: Languages, Government Printing Office, 1978, pp.98-102, https://books.google.com/books?id=-RnOijPup3YC (last checked July 8, 2017)

6. "Upper Mattaponi Tribe." Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, May 30, 2014, https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Upper_Mattaponi_Tribe (last checked July 8, 2017)

7. "Bulletin of the Virginia State Library," Volume 9, 1916, p.191, http://books.google.com/books?id=uTBVAAAAYAAJ; "Shenandoah," Online Etymology Dictionary, http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=Shenandoah; "Sports," Shenandoah Central Schools (New York), http://www.shenet.org/grapevine/Archives/sports.htm (last checked September 21, 2013)

8. "Guide to Shenandoah National Park and Skyline Drive," Shenandoah National Park Association, http://www.guidetosnp.com/web/Information/ShenandoahNationalPark.aspx (last checked September 21, 2013)

Siouan-speaking tribes in Virginia's Piedmont were isolated from the Siouan-speaking tribes in the Great Plains

Source: New York Public Library, Linguistic families of American Indians north of Mexico

"Indians" of Virginia

Virginia Places