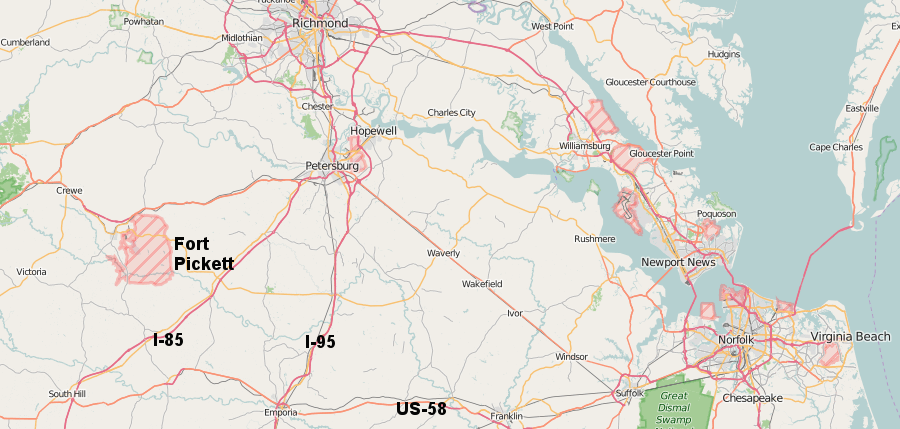

Fort Pickett was located where farms and forested land could be acquired quickly, and close to the embarkation port at Newport News from which soldiers and equipment were shipped to Europe and New Guinea

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Fort Pickett was located where farms and forested land could be acquired quickly, and close to the embarkation port at Newport News from which soldiers and equipment were shipped to Europe and New Guinea

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

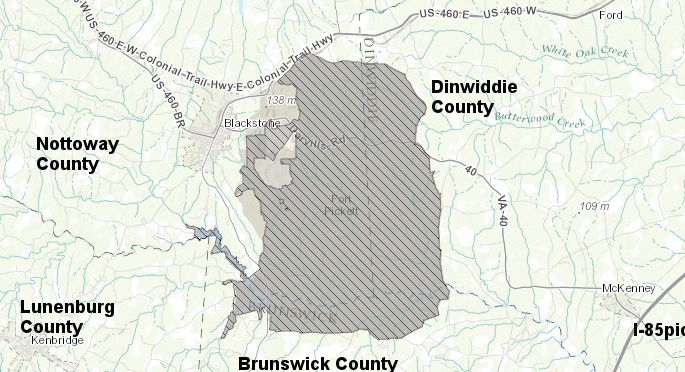

Camp Pickett was created in 1942, at the start of World War II. The Army selected the site of a former Civilian Conservation Corps camp near Blackstone, Virginia, in Nottoway, Dinwiddie, Lunenburg, and Brunswick counties. The military purchased over 40,000 acres and built 1,000 barracks (plus and water and sewage plants) for enlisted soldiers to use during basic training.

The base name honored General George Pickett, a Confederate general famed for his failed charge on the third day of the battle at Gettysburg.

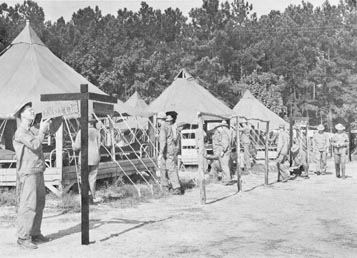

In addition, the Army built Blackstone Army Airfield. It was an "Army" airfield; the US Air Force had not been established yet as a separate service.

The 79th Infantry Division was based at Camp Pickett. Other units that used the vast acreage of woods and fields at Fort Pickett before being shipped to Europe and New Guinea in the Pacific Theater included the 3rd Infantry Division and the 3rd Armored Division, plus the 28th, 31st, 45th, 77th, and 78th divisions. The camp became a training center for different types of specialty schools, training cooks, clerks and ambulance drivers as well as combat hospital medical corpsmen.1

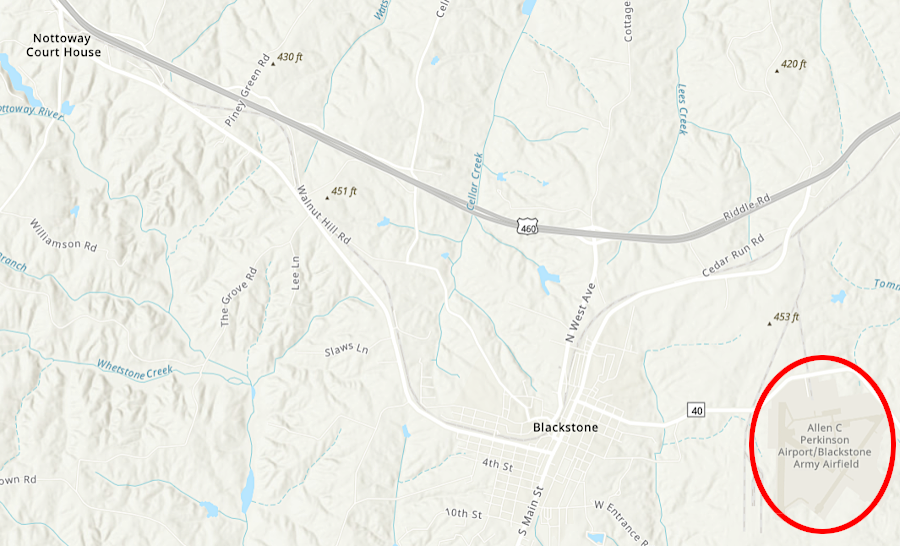

clerk-typists were trained at Camp Pickett

Source: US Army Medical Department, Medical Training in World War II (Figure 26)

Two new railroad spurs enhanced transportation to the port of embarkation at Newport News. Camp Pickett was used for training large units in large-scale maneuvers, prior to shipment overseas. Up to 25 trains were required to move the 15,000 men in a division to Camp Patrick Henry at Newport News.2

In 1941, the War Department created its first two Medical Replacement Training Centers to train the support staff for doctors, ranging from enlisted men who would provide first aid on the front lines to veterinary technicians. One center was placed at Camp Lee near Petersburg, but the same facility was also used to train quartermasters responsible for supplies and the camp became overcrowded. Somewhat ironically, the camp responsible for teaching the logistics of supply lines was unable to obtain enough supplies for the soldiers.

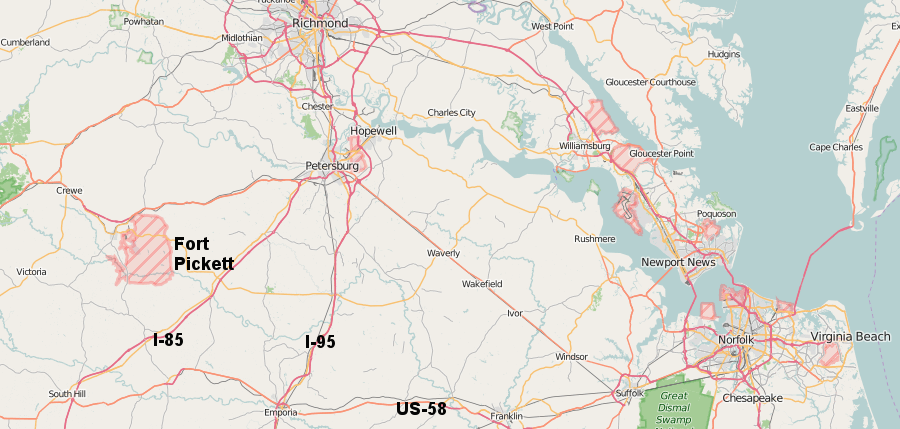

trainees at Camp Pickett were housed initially in tents

Source: US Army Medical Department, Medical Training in World War II (Figure 20)

The solution was to move the medical trainees to Camp Pickett, 40 miles away. One option for the transfer was to wait until each medical battalion completed its cycle of training and then move that unit to Camp Pickett, but that required maintaining two partially-staffed Medical Replacement Training Centers for 10 weeks. Instead, all the trainees marched for three days from Camp Lee to Camp Pickett, with the heaviest supplies transported in trucks.

the first medical trainees arrived at Camp Pickett after a 3-day, 40-mile march from Camp Lee

Source: US Army Medical Department, Medical Training in World War II (Figure 19)

The Medical Replacement Training Center was expanded in 1942 to include training of black as well as white soldiers. The Army was segregated by race at the time, and the medical department also maintained separate companies and battalions of black soldiers. The 357th Engineering Service Regiment, composed of black soldiers who had enlisted or were drafted, provided maintenance services at the base. Separate facilities, including chapels and movie theaters, were constructed for that unit.

Specialized medical training at Camp Pickett ended in October 1943; other Medical Replacement Training Centers filled the need after that date. Camp Barkeley in Texas absorbed the responsibility for training the black medical corps. Over 90,000 soldiers moved through the Medical Replacement Training Centers at Camp Pickett and its predecessor at Camp Lee between 1941-43.3

trainees negotiated the obstacle course at Camp Pickett under live machine gun fire

Source: US Army Medical Department, Medical Training in World War II (Figure 29)

When the Army closed the Medical Replacement Training Center in 1942, it made Camp Pickett a hospital center for sick/wounded soldiers returning from Europe. Barracks were converted into medical wards, and the General Hospital had 2,700 beds at one point. The medical services for returning soldiers also included four dental clinics.

After the North Africa campaign resulted in a large number of German prisoners, many were shipped across the Atlantic Ocean to prisoner-of-war camps in North America. In Virginia, there were 6,000 German prisoners at Camp Pickett soon after World War II ended.4

After World War II, the prisoners-of-war were returned to Germany and Camp Pickett was placed on standby status. It was reactivated in 1948 as the Cold War heated up with the Berlin Crisis.

The 17th Airborne Division trained at the camp in 1948. In 1950, the facility began to host annual summer training exercises by the Virginia and Maryland National Guard, plus specialized training by other units.

In 1974, the Defense Department reclassified Camp Pickett as Fort Pickett. That indicated the military planned to retain facility in the long-term for training, and the first permanent brick buildings were finally constructed at the site. Prior buildings had been temporary structures, primarily built from wood.

The first two Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) reviews did not consider closing Fort Pickett, but state and local officials were aware that the military considered the site to be underutilized with low military value. The Nottoway Economic Development Commission proposed converting the airfield into an agricultural import-export center. Livestock and horses would be shipped by 747 airplanes, and the site would become a free trade zone to facilitate exports. It was not an economically feasible project, and was never funded.

In 1995, the Defense Department finally included Fort Pickett on the BRAC review list. Local and state officials were alarmed at the potential loss of jobs. The town of Blackstone, which had become "a giant off-base trading post," essentially closed down in 1946 until the 1948 re-activation. If the base closed, that rural area of Virginia would struggle to find new employers.

The final decision was to dispose of only 3,600 acres and to retain over 40,000 acres as a training facility for National Guard units, but to transfer the Army troops to another facility. Unneeded land was transferred to local governments, including the Town of Blackstone and Nottoway County.

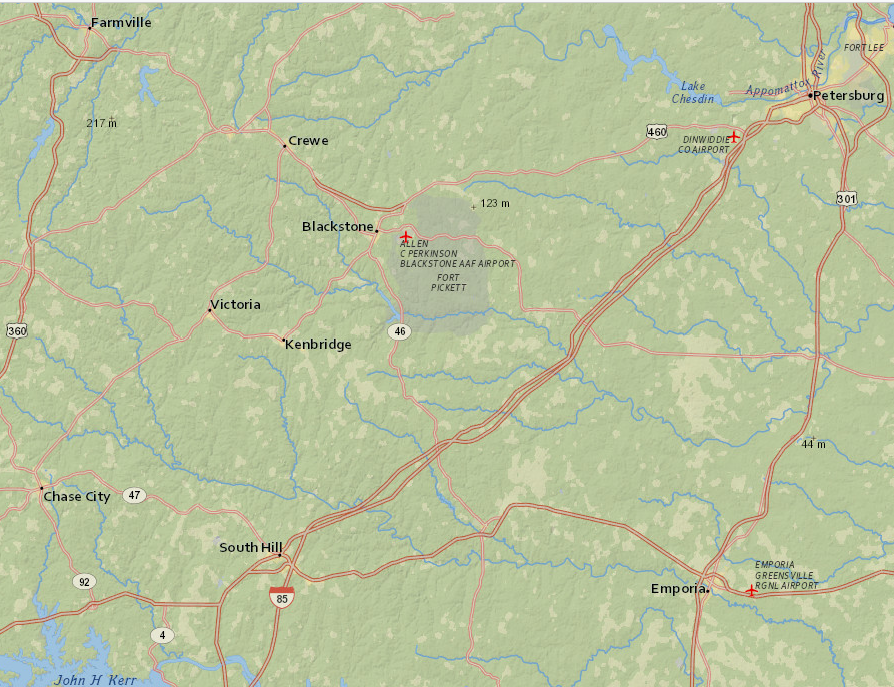

The 600-acre Allen C. Perkinson Airport (Blackstone Army Airfield) ended up jointly owned by the US Army and the Town of Blackstone. In September 2023, it received the first approval issued by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to operate a "vertiport" at an unused taxiway on the airport's north side. The advanced air mobility industry was focused on electric vertical takeoff and landing aircraft transporting both cargo and passengers, and the Federal Aviation Administration needed to develop design standards and operational regulations for vertiports.

the US Army and Town of Blackstone jointly manage Allen C. Perkinson Airport (Blackstone Army Airfield) now

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

To help offset the economic impact of the BRAC decision, the General Assembly transferred the headquarters office of the Virginia National Guard and the rest of the Virginia Department of Military Affairs to Fort Pickett in 1998.

Fort Pickett itself was inactivated as a US Army base. The site given to the Virginia National Guard, which has managed the training ground since 1997. The Army National Guard Maneuver Training Center located there is:5

over 90% of the land Fort Pickett was kept in military use for training National Guard units after the 1995 Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) process, but the airport and excess land were transferred to local governments

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 2008, the State Department proposed building a Foreign Affairs Security Training Center, a consolidated facility to prepare 1,500 Foreign Service Officers assigned to protect embassies, consulates, and other US offices in foreign countries. It was the latest of several proposals to consolidate training at over 15 separate sites. The US Congress funded the proposal, after which the State Department and the General Services Administration began a search that concluded Fort Pickett was the least expensive and most convenient site.

Other locations were considered. After two embassies in Kenya and Tanzania were destroyed by bombs in 1998, the National Security Council had proposed establishing a Center for AntiTerrorism and Security Training at Indian Head Naval Surface Warfare Center in Maryland, across the Potomac River from Fort Belvoir. In 2002, the proposed location was shifted to Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland, but nothing was constructed.

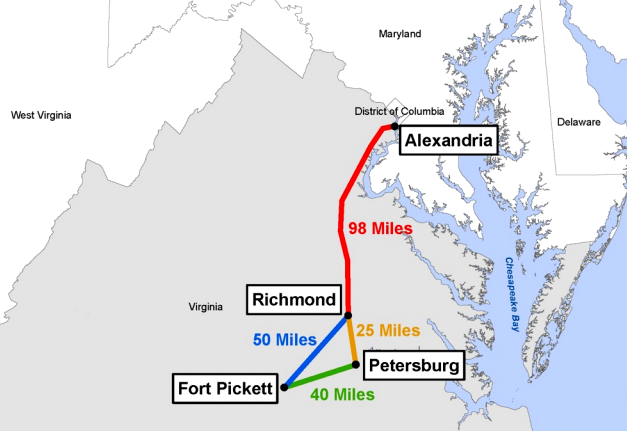

The threat expanded after the United States invaded Iraq in 2002 and the international terror campaign against overseas US facilities intensified. In 2005, the State Department opened an interim facility at a racetrack in Summit Point, West Virginia. Drivers practiced escape maneuvers on the tracks, and a firing range was installed. Primary factor in choosing a site was proximity to Washington, DC, where many of the personnel to be trained annually were already working.

Alternatives to Fort Pickett included the existing Secret Service training center in Beltsville, Maryland, and the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Advanced Training Center in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. Over 70 properties were considered, and the initial preference was undeveloped land known as Hunt Ray/Crismer Farms in Queen Anne's County, Maryland. Plans expanded to train 10,000 people annually, and local opposition to development on the Eastern Shore ended further consideration of the Queen Anne's County site.6

The 2012 attack on the US compound in Benghazi, Libya, illustrated the threat, but did not end the dispute over locating the Foreign Affairs Security Training Center. Members of the Georgia delegation in the US Congress proposed that the State Department use the Department of Homeland Security's Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC) at Glynco, Georgia.

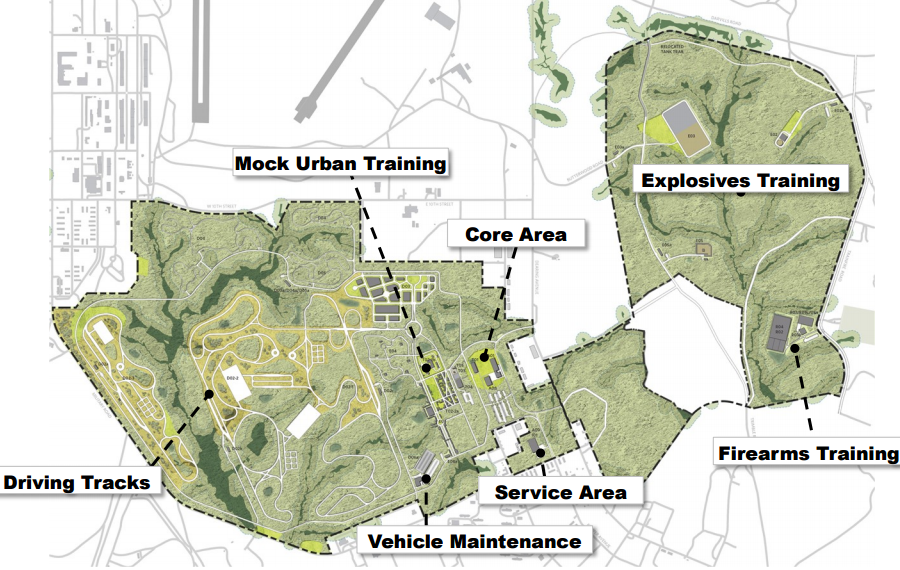

The Government Accountability Office reported that the site in Virginia was not more expensive than the Georgia site once the State Department had reduced the scope to eliminate facilities for much of the "soft skills" classroom training, and offered advantages in four particular ways. Fort Pickett:7

- consolidated training more completely at one location, whereas Glynco required some activities (including use of explosives greater than three pounds and nighttime helicopter flights) to occur at the Townsend Bombing Range about 30 miles away

- imposed fewer restrictions on nighttime training

- required half the travel time (three hours by car vs. six hours by plane) from DC, from which many of the trainees would travel while attending the Foreign Service Institute in Arlington, Virginia

- offered exclusive use of the training facilities, such as the tracks for training drivers in evasive maneuvers and high-speed escapes from an ambush

Fort Pickett was preferred over the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC) at Glynco, Georgia in part because the Virginia location was closer to other State Department offices and training facilities in DC and Arlington

Source: State Department, FASTC SDEIS Public Meeting Presentation (February 3, 2015, Slide 8)

The Virginia National Guard contributed most of the land required for the State Department project, but the General Services Administration purchased one parcel in Nottoway County. The 725-acre property had been transferred during the BRAC process to the Local Redevelopment Authority in Nottoway County and included within an industrial park, so the Federal government had to re-purchase that land.

There was strong local support in Nottoway County. In contrast to the proposed location at Hunt Ray/Crismer Farms in Queen Anne's County, Maryland, the local residents near Fort Pickett were accustomed to artillery fire, helicopter flights, and other noises associated with military training.

military units practice live fire operations at Fort Pickett, day and night

Source: Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, EOD technicians practice combat skills

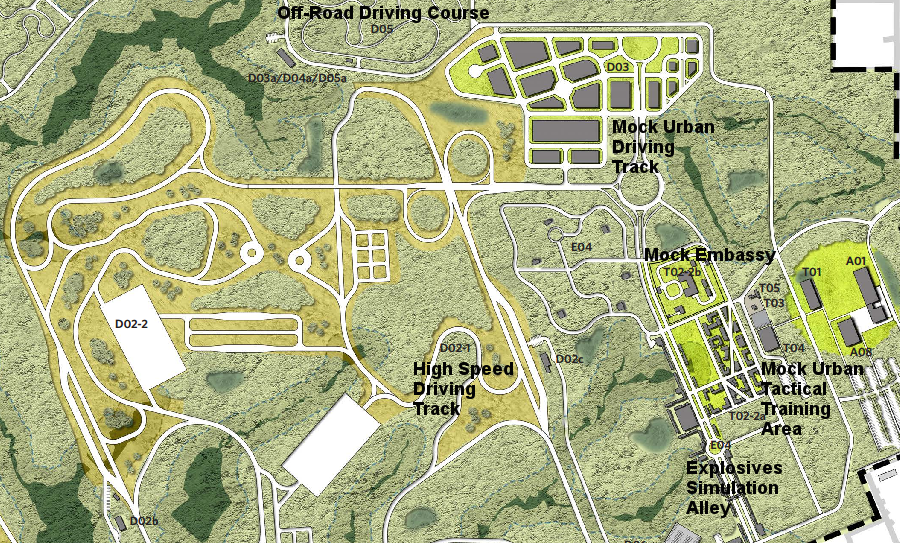

In addition to creating construction jobs over four years, the new Foreign Affairs Security Training Center will create long-term service jobs. Private development of hotels in Blackstone was expected to house the 600 students getting trained each week. Rifle ranges at Fort Pickett were the only existing capabilities included within the proposal. All other training would be done in newly-constructed facilities, including:

Fort Pickett was preferred in part for the site of the Foreign Affairs Security Training Center (FASTC) because new facilities there would offer exclusive use for training State Department personnel and its security partners

Source: State Department, FASTC Supplemental Draft EIS Public Meeting Posters (February 3, 2015)

Prior to opening of the Foreign Affairs Security Training Center in 2019, local officials predicted 200-400 families would move permanently to the area. The business development manager at South Hill sought to recruit as many as 100 of them to live in that town. South Hill is 30 miles away from the training center, but town officials highlighted the quality of local schools, the presence of the VCU Health Community Memorial Hospital nearby, and the potential of a 30-mile commute requiring only 30 minutes.

Town officials recognized that their competition for new residents included Blackstone, Farmville, Colonial Heights (next to Fort Lee), plus unincorporated places in Lunenburg, Nottoway and Brunswick counties. They emphasized the quality of their town's life, with good schools, hiking, biking, vibrant civic groups, and the potential of high-speed internet service.

To attract residents, South Hill viewed its small town "social capital" as its greatest asset. The town manager noted that distance was not the only factor to consider, and South Hill was:9

South Hill sought to attract 100 families moving to the area to work at the Foreign Affairs Security Training Center

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

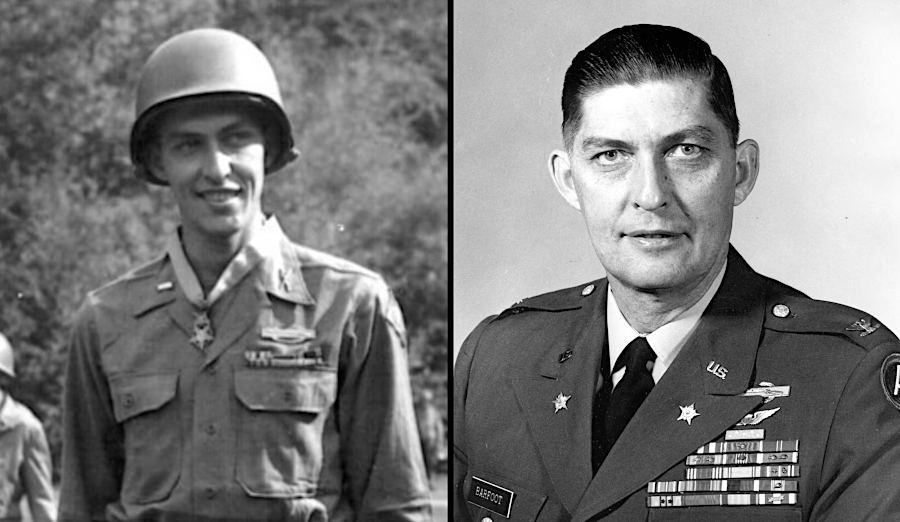

In 2022, the US Army's Naming Commission proposed renaming Fort Pickett after T/SGT Van T. Barfoot, as part of a Defense Department initiative to replace names that honored aspects of the Confederacy. Technical Sergeant Van T. Barfoot had earned the Medal of Honor fighting in Northern Italy in 1944. In his 34 years of military service, he also earned the Silver Star, the Bronze Star, three Purple Hearts, two Legions of Merit, and 11 Air Medals.

Barfoot was a technical sergeant when he earned the Medal of Honor, and retired as a colonel

Source: Virginia National Guard, Va. National Guard training center to be redesignated Fort Barfoot

In addition to changing the name of Fort Pickett, new names were proposed for four buildings, 19 roads and five bridges carrying names associated with the Confederacy.

Camp Pickett had been dedicated on July 3, 1942, 79 years after Pickett's charge at Gettysburg. The name and dedication date in 1942 were chosen by the War Department, and locals had no influence. Locals were invited in 2022 to suggest new names for Fort Pickett.

The name change to Fort Barfoot became official on March 24, 2023, also a time chosen by Defense Department officials based at the Pentagon. Fort Pickett became the first of the nine military bases renamed according to the recommendations of the Naming Commission.

Barfoot's grandmother was a member of the Choctaw Nation. That nation and Virginia tribes were invited to participate in the re-naming ceremony, and they provided singing and dancing. A descendant of a Black landowner who had been forced to sell in 1942 contacted the Defense Department after seeing a story about the name change. She was quickly invited to the event, but the ceremony was not revised to include a public acknowledgement of the former landowners.

A local restaurant owner commented about the 41,000-acre facility which employed 1,000 people:10

President Trump announced in June 2025 that the name Fort Pickett would be restored. He had the authority to change the name of Fort Barfoot, but was prohibited by law from naming a military base after a Confederate.

The US Army identified another person with the last name of Pickett. First Lieutenant Vernon W. Pickett had won the Distinguished Service Cross in World War II, so technically Fort Pickett would honor him.11

most of the land needed for the Foreign Affairs Security Training Center came from Fort Pickett, including the area intended for explosives training

Source: State Department, FASTC SDEIS Public Meeting Presentation (February 3, 2015, Slide 12)