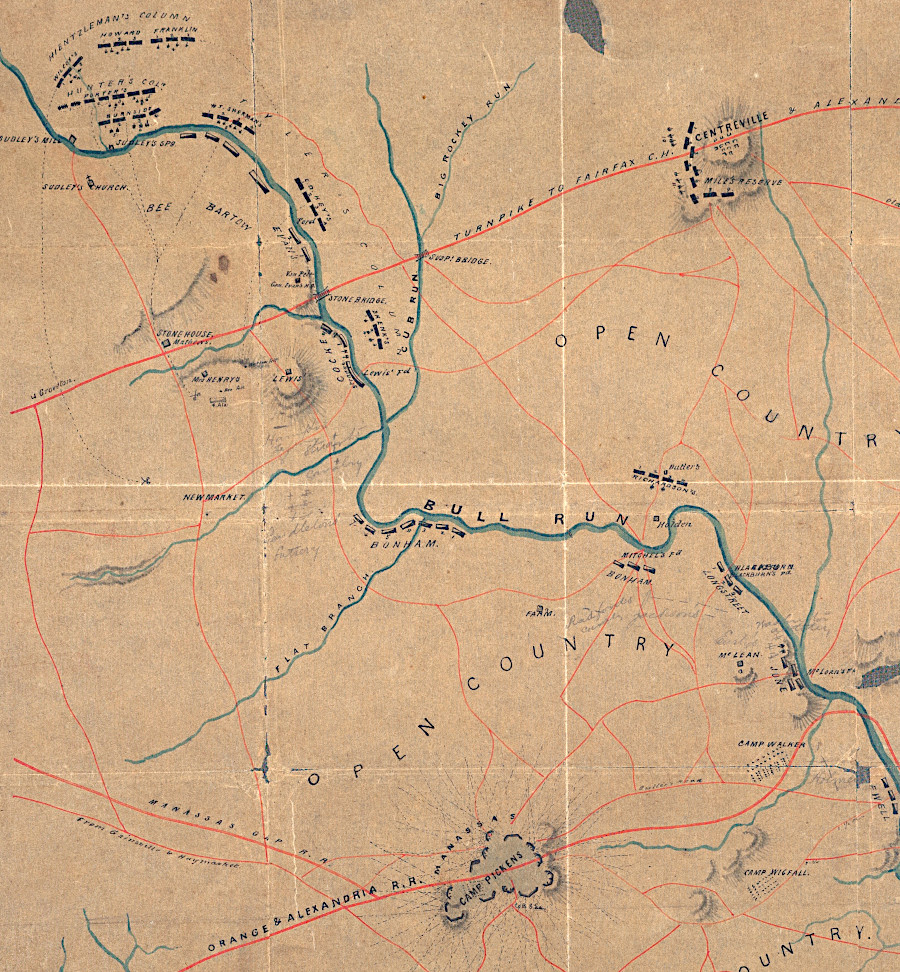

Map of Virginia at time of Civil War (Union march from Alexandria to Manassas was through Fairfax Courthouse and Centreville)

Source: Library of Congress

Map of Virginia at time of Civil War (Union march from Alexandria to Manassas was through Fairfax Courthouse and Centreville)

Source: Library of Congress

After Virginia's special convention approved and ordinance of secession in April, 1861 to join the Confederacy, the Confederate capital was moved from Montgomery, Alabama to Richmond, Virginia. (Technically, Virginia's secession from the Union did not become official until May 24, 1861, after Virginia voters ratified the decision of the secession convention.)

Moving the capital to Richmond put the southern rival to Washington DC just 100 miles away. That's why the first large-scale invasion of the Confederacy was in northern Virginia at Alexandria, and the first major battle occurred two months later at Manassas.

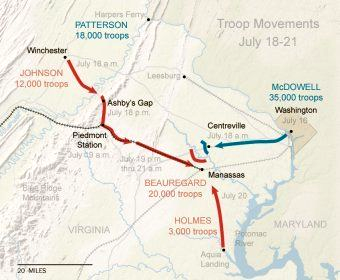

the Confederate army in the Shenandoah Valley marched across the Blue Ridge and rode the Manassas Gap Railroad eastward in mid-July, 1861; those extra forces on the battlefield were key to the Confederate victory at First Manassas

Source: National Park Service, A New Economy of War

Pro-secession advocates, especially the "fire eaters" from South Carolina, thought that any military action would be short and that the Confederacy would easily prove it could protect its borders. Southerners had composed most of the volunteers in the 1846-48 Mexican War. A Confederate army composed of another generation of Southern volunteers was projected to achieve an equally-swift and complete military victory if a Union army invaded; the amount of blood that would be shed was predicted to be so small that it would only fill a thimble used for sewing.1

After declaring secession, the Confederacy simply needed to survive in order to prove it was an independent nation. The Union, on the other hand, needed to demonstrate it still controlled all of its southern territory, and that 11 seceding states were still part of the United States rather than a separate country. Otherwise, European nations would recognize the Confederacy and provide political, economic, and military support - just as France had provided essential resources for 13 rebellious colonies in 1776-1783, to establish their independence from Great Britain.

To end the rebellion, the Union needed to ensure the Confederacy did not survive. In 1861, the easiest way to destroy the upstart government in the southern region was to capture Richmond, the new capital of the Confederacy. If the Confederacy could not defend its own capital, then clearly European nations would not recognize the Confederacy as independent... no matter how much England wanted to see the United States dissolve into less-powerful fragments.

By 1865, it would no longer be true that capturing Richmond would end the war. As the war continued past 1861, the Union dropped its "soft war" efforts to woo the southern states into rejoining the "Union as it was, the Constitution as it is." When President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in September, 1862, he shifted the war aims of the Union. Freeing the slaves, as proposed in the Emancipation Proclamation, involved a massive revision of southern wealth/power and required amending the Constitution. More than capture of territory would be required to end the Southern way of life, based on slavery.

In April 1865, the Union did capture Richmond. By then, everyone knew that "victory" required capturing the armies more than capturing the capital city of the Confederacy. General Grant's mission was accomplished only after Lee surrendered at Appomattox, and the Civil War ended only after all the other remaining southern armies also surrendered soon afterwards.Technically, Virginia's secession from the Union became official on May 24, 1861. Early that morning, Union troops crossed the Long Bridge and marched along the extension of the C&O Canal between Aqueduct Bridge and Alexandria. At the same time, Union forces were carried across the Potomac and landed at the Alexandria wharfs.

As the Union forces entered Alexandria, the 17th Virginia Regiment retreated westward. No fighting occurred, except when the commander of the Union forces (Elmer Ellsworth) tore down the Confederate flag flying over a hotel at King and Pitt Street. James Jackson, manager of the Marshall House, shot Ellsworth and was killed in return by a Union soldier.2

Colonel Ellsworth was killed at the Marshall Hotel, on the intersection of King and Pitt

Source: Library of Congress Plan of Alexandria at time of Civil War

Marshall Hotel in August, 1862

Source: Alexander Gardner, Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War

Seizing Alexandria was a tactical move to protect Washington DC. It eliminated the risk of Confederates placing cannon on the hills of the city and shelling the Capitol or the White House. Alexandria remained in firm control of the Union throughout the Civil War - and between 1863-65, the administration of Abraham Lincoln treated Alexandria as the official capital of Virginia. (Some old Virginia families living south of the Rappahannock River talk as if Northern Virginia has been "occupied" ever since 1861...)

Source: Gettysburg National Military Park Winter Lecture Series, Debacle at Balls Bluff: The Battle that Changed the War

Source: American Battlefield Trust, Why the Battle of Ball's Bluff is Important: 160th Anniversary

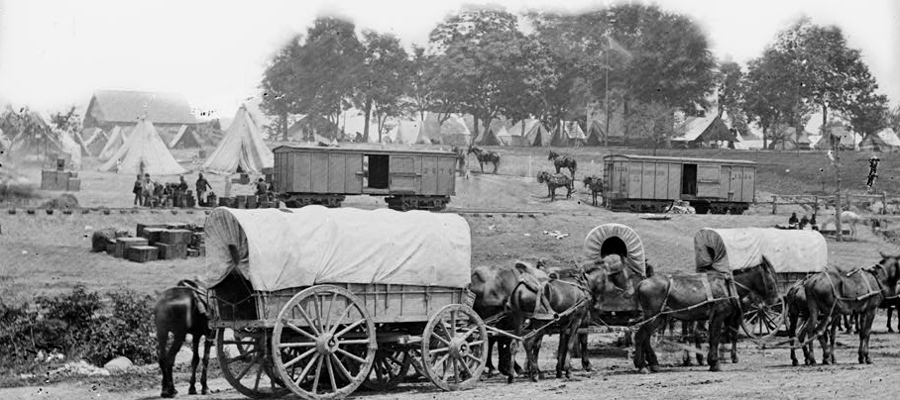

After seizing Alexandria on May 24, 1861, the Union Army was still 100 miles north of Richmond. To get there, it would have to march, carrying food/ammunition for soldiers and hay for horses pulling the supply wagons. To minimize the logistical challenge, the Union planned to rely upon the railroads that connected Alexandria and Richmond.

boxcars pulled by locomotives could carry more supplies than wagons pulled by horses

Source: Library of Congress, Savage Station, Va. Headquarters of Gen. George B. McClellan on the Richmond & York River Railroad

Today, there is a rail line running due south from Alexandria, going through Woodbridge, Quantico, then Fredericksburg to Richmond. In 1861, however, there was a gap between Alexandria and Fredericksburg.

Boats carried freight and passengers down the Potomac River from Washington/Alexandria to Aquia, near Fredericksburg. The boats docked at Aquia, where passengers and freight transferred to the railroad. It was known appropriately as the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac (RF&P) - not the Richmond and Alexandria - because the northern end of the RF&P railroad was the Aquia docks on the Potomac River rather than the port of Alexandria.

map showing railroad links between Alexandria to Richmond, 1861

Source: Library of Congress

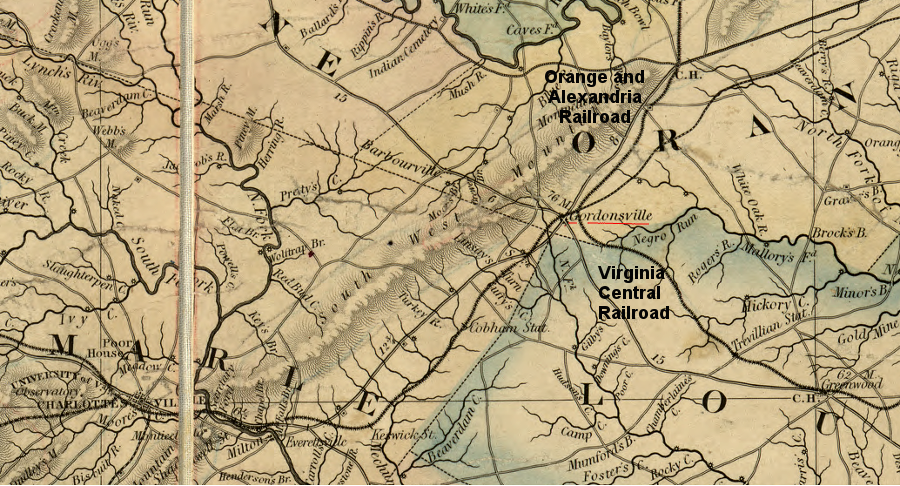

There was no Richmond and Alexandria Railroad, but there was a rail line leading west of Alexandria - the Orange and Alexandria, built to facilitate trade with farmers east of the Blue Ridge. The Orange and Alexandria connected with the Virginia Central at Gordonsville.

Orange and Alexandria Railroad trains ran from Alexandria to Gordonsville, and Virginia Central Railroad trains ran from Gordonsville to Richmond, so the Union Army calculated it could supply an army marching "On to Richmond" if the troops marched parallel to the tracks

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the state of Virginia, constructed in conformity to law from the late surveys authorized by the legislature and other original and authentic documents (1859)

A Union Army that seized control of the Orange and Alexandria and the Virginia Central railroads could carry lots of supplies in rail cars pulled by locomotives, reducing the number of horses. The route through Manassas and Gordonsville would involve a curving path to the west initially, and longer than a direct march south from Alexandria - the logistical support from railroad transport would make an attack on Richmond much easier.

Union General Irvin McDowell planned to get to Richmond via the Virginia Central, going from Gordonsville to the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad and then turning south to the Confederate capital

Source: Library of Congress, Colton's Virginia (by J. H. Colton, 1855)

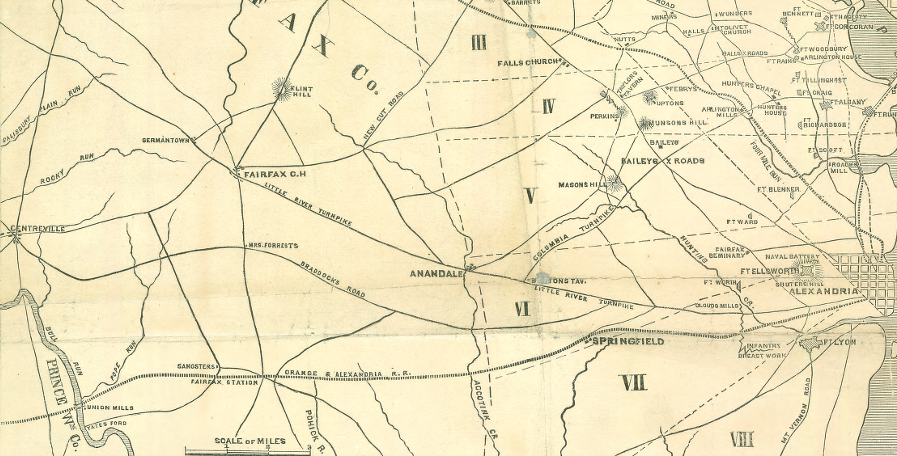

So in mid-July, 1861, the Union Army marched west through Fairfax Court House to Centreville. The army marched in three columns, slowing at every report of Confederate forces that might resist their advance. The first units reached Centreville on Thursday, July 18.

there were few routes between Alexandria and Centreville in 1861

Source: Library of Congress, The National lines before Washington (published in the New York Times, 1861)

Union forces sparred with Confederates on July 19, 1861 at the fords of the Bull Run, especially between Centreville and Manassas where Route 28 and Old Centreville Roads cross the stream from Prince William County to Fairfax County.

the Union Army under General Irvin McDowell used the Warrenton-Alexandria Turnpike in Centreville between July 18-20, 1861 - and retreated by that same route on July 21

Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, Eye of the Conflict (p.149)

Two days later on July 21, the Union Army faked at attack across Bull Run at the Stone Bridge of the Alexandria-Warrenton Turnpike (modern Route 29). General Irvin McDowell, commanding the Union forces, sent most soldiers on a long march in a "right hook" to cross Bull Run at Sudley Springs (where Route 234 crosses today), while other troops crossed at Red House Ford north of the Stone Bridge.

in 1861 Union forces feinted at the Stone Bridge over Bull Run, and marched upstream before crossing the stream

Source: National Archives, Manassas and Bull Run Battlefields, Virginia

The maneuver worked initially. By early afternoon of that hot July day, McDowell thought he had won a glorious victory. However, Confederates blocked further advance down the road from Sudley Springs to the railroad depot in Manassas, especially when General Thomas Jackson ordered his soldiers to "stand like a stone wall" rather than retreat. During the day, more Confederates soldiers arrived on trains, which hauled most of a separate Confederate army that had been in the Shenandoah Valley. The extra soldiers proved to be the turning point, finally forcing Union forces to retreat back to Alexandria/DC.

map showing Union path of attack to Henry Hill and Chinn Ridge on July 21, 1861 at First Battle of Manassas

Source: Library of Congress

The result: the march on Richmond was stopped in 1861. The Union forces spent the winter in Alexandria and DC. The Confederates built fortifications in Centreville, Manassas, and along Bull Run to Occoquan. Throughout the winter, Confederate cavalry patrolled to the hills overlooking Alexandria, including Munson's Hill and Upton Hill in modern-day Arlington County.

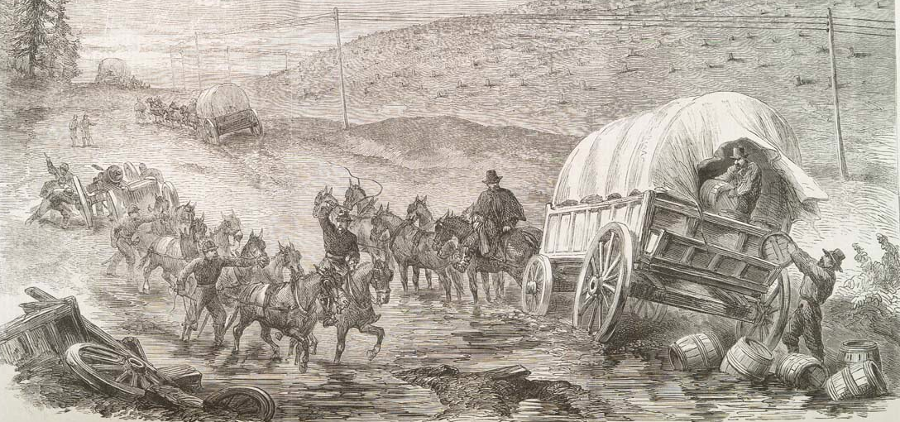

Little fighting occurred that winter, or in other winters during the Civil War. Soldiers stayed in "winter quarters" because winter rains left roads frozen and muddy, impassable to armies hauling heavy artillery and wagons. Civil War fighting was typically between May-October, due to the transportation constraints.

during the Civil War, fighting between large units was rare between January-April because roads were too muddy and forage for horses was too scarce

Source: Illustrated London News, The Civil War in America: Baggage-Waggons and Gun-Carriages of the Army of the Potomac on the Move (April 5, 1862)

After its defeat in July 1861, the Union Army recruited soldiers, gathered supplies, and trained under new leadership. General McClellan figured out a different way to move the Union army 100 miles south, and started on a separate path to Richmond in March, 1862.

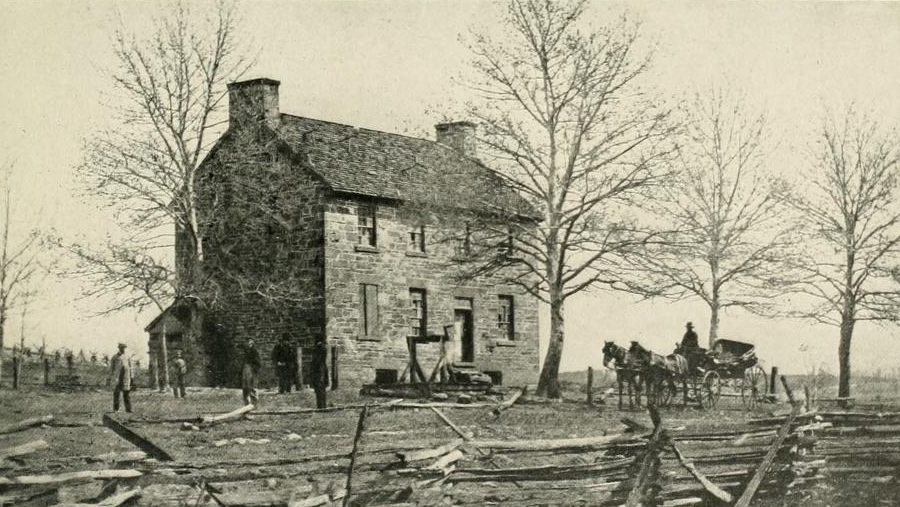

Liberia served as the headquarters for Confederate General P. G. T. Beauregard before First Manassas in 1861

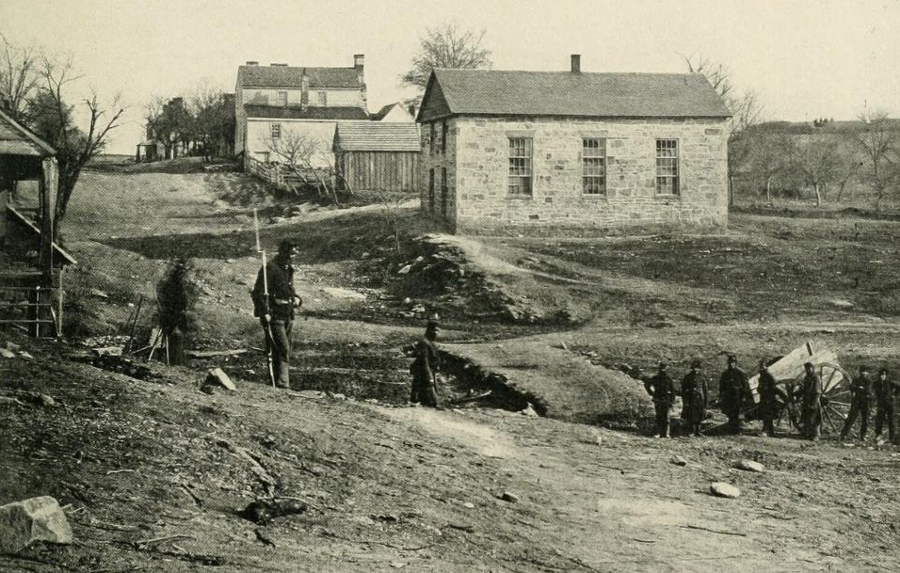

Stone House at Manassas Battlefield

Source: History Channel, Civil War Combat: The Battle of First Manassas

Source: LionHeart FilmWorks, Civil War "Battle of Manassas (Bull Run)" - Complete 125th Anniv. Re-enactment

General P.G.T. Beauregard, the Confederate general in charge at Manassas before the battle in July 1861, used the plantation house at Liberia as his headquarters

Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, General Beauregard's Headquarters (p.152)

the Union Army splashed across Sudley Springs Ford and marched past the John Thornberry House on the morning of July 21, 1861

Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, Thornton's House - Bull Run, July 21 1861 (p.154)

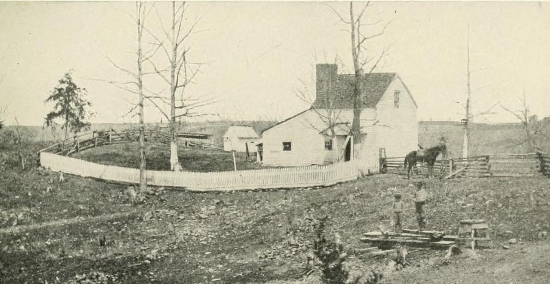

"Gentleman Jim" Robinson, a free black man related to Judith Henry, owned a farm on the northeastern edge of Henry Hill

Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, Here Stonewall Jackson Won His Name (p.156)

the old toll house of the Warrenton-Alexandria Turnpike became known after the battles at Manassas as the "Stone House"

Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, Where the Confederates Wavered (p.156)

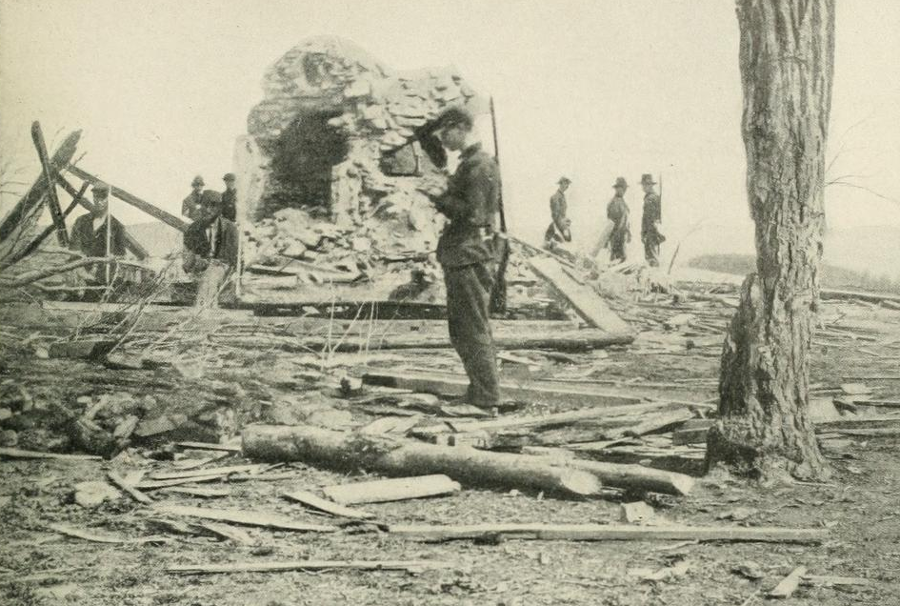

the Henry House was destroyed during First Manassas, and Judith Henry was the only civilian to become a combat casualty that day

Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, The Storm Center of the Battle, Bul Run, July 21, 1861 (p.158)

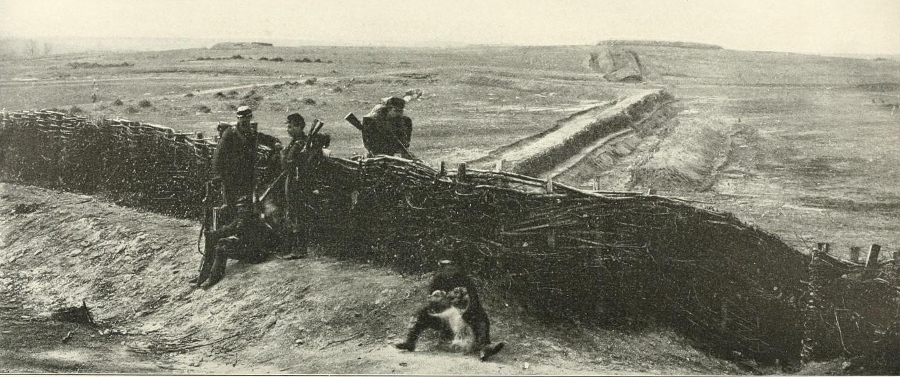

Confederates built defensive lines near Manassas and Centreville in 1861 after First Manassas, then abandoned them in March 1862 when troops moved to Richmond to counter the Peninsula Campaign

Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, The Lost Chance - Confederate Fortifications at Manassas (p.160)

Confederates troops cleared the land near Centreville in 1861 to get wood for fortifications and fires for cooking/heating

Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, Work Thrown away - Confederate Fortifications at Centreville (p.166)

Confederates retreating from Centreville area in 1862 replaced cannon in forts with "Quaker guns" to deter attack

Source: Alexander Gardner, Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War

alignment of Confederate and Union forces at the start of the 1861 fighting at Manassas

Source: Civil War Book Review, An Accomplished Confederate Cartographer Maps the Manassas Battlefield (by Lon Joseph Fremaux, 1861)

Thomas Jackson earned the nickname "Stonewall" at First Manassas on July 21, 1861

Source: Library of Congress, Stonewall Jackson, Bull Run, Aug. 17, 1861 (by Henry Alexander Ogden, c.1900)