So How Do We Describe Military Conflicts Without Igniting Passions Again?

early European explorers discovered Native American towns surrounded by wooden palisades; warfare was common long before the Spanish, French, English, Dutch, and Swedes arrived

Source: Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, Theodor de Bry, Brevis narratio eorum quae in Florida Americae provincia Gallis acciderunt ... : quae est secunda pars Americae (1591)

From the English point of view in the 1600's, the Native Americans were heathen savages. Warfare between the colonists and the Powhatan tribes was described in pejorative terms, between good vs. evil societies.

For centuries, Virginia history books referred to 1622 and 1644 as massacres, starting with the Virginia's Company's official report of the 1622 event titled A Declaration of the State of the Colonie and Affaires in Virginia, With a Relation of the barbarous Massacre in the time of peace and League, treacherously executed upon the English by the Infidels, 22 March last. Together with the names of those that were then massacred; that their lawfull heyres, by this notice giuen, may take order for the inheriting of their lands and estates in Virginia.1

Clearly that word massacre is a pejorative term. It suggests that the English were innocent and the moral blame for deaths should be placed on just the Native American side. Alternative choices with different emotional connotations include assault, uprising, even attack.

- A current scholar refers to the Native American action in 1622 as "The First Act of Terrorism in English America." He defined "terrorism" as a:2

- calculated, purposeful (never "senseless") use of violence against unsuspecting citizens of an enemy power in order to make noncombatants experience the pain and suffering that their society has inflicted on others.

Europeans got a grisly interpretation of the uprising led by Opechancanough on March 22, 1622

Source: 1622 massacre jamestown de Bry (by Theodore De Bry, 1628)

If various Native American tribes had somehow acquired cannon and marched into battle in the European fashion, the warfare (and the descriptions...) of the 1622 and 1644 events might have been different.

Powhatan and Opechancanough, facing an occupying force that had overwhelming technological superiority, did not fight in the fashion of the English. They found their enemy's weak points and competed using techniques where Native American's capabilities would have the greatest impact on the enemy.

Native Americans fought the English colonists at Jamestown with the tools they had. The English indicated, with words like massacre, that fighting with different techniques was less moral than fighting the English way.

Historians are increasingly describing the shifting boundary between colonial and Native American settlement as the "backcountry" rather than the "frontier," to minimize the impression that it was natural for Europeans to advance settlement westward and for Native Americans to surrender their land.

Many museum exhibits and historic signs still use emotionally-charged language to describe the Anglo-Powhatan wars and the 1861-1865 American Civil War (also known as the "War of Northern Aggression" in some unReconstructed parts of Virginia). Changing traditional descriptions of military events in Virginia can be controversial. When the visitor center at Manassas National Battlefield Park was redesigned in the 1990's and the prominently-displayed Confederate flag was removed, the National Park Service received complaints about political correctness.

Categorizing someone today as a terrorist may be correct, but such a term also adds an emotional component comparable to characterizing the 1622/1644 events as massacres.

In the Civil War, the Confederates developed the land mine and armored ships to overcome the numerical advantages on the Union side. Warfare planning requires expecting the unexpected, and modern defense training highlights the need to prepare for asymmetric threats. The biases associated with describing asymmetric warfare are incorporated into the language used to describe events:3

- Put simply, asymmetric threats or techniques are a version of not "fighting fair," which can include the use of surprise in all its operational and strategic dimensions and the use of weapons in ways unplanned by the United States. Not fighting fair also includes the prospect of an opponent designing a strategy that fundamentally alters the terrain on which a conflict is fought.

A conversation requires using words. We read and talk about people, places, and things in order to understand why things happened, why they happened where they happened, and why they happened when they happened. Such conversations are more constructive when all parties having a discussion are willing to define and refine their terms so their statements are understood.

The 400th anniversary of the arrival of the English at Jamestown was in 2007. Initially, various initiatives were planned to celebrate the anniversary. Some Native Americans in Virginia were openly reluctant to join in a celebration of the arrival of the English in 1607. After all, the settlement at Jamestown led to a drastic decline in the Native American population and a massive alteration of the traditional cultures in Virginia.

The state government finally decided to commemorate rather than celebrate the 400th anniversary in 2007, in order to minimize the risk of a Native American boycott. Politics is the art of the possible, and the artful choice of words enhanced the potential economic impact of increased tourism to the Peninsula during the 400th anniversary.

brochure celebrating 350th anniversary of Jamestown in 1957

Source: EBay

Dealing with the Confederate heritage in Virginia is at least as challenging. Since 1889, Virginia has recognized Robert E. Lee's January 19 birthday as a state holiday. The state honored "Stonewall" Jackson by adding his name to the holiday in 1904. After the Federal government adopted the third Monday in January as a Federal holiday in 1983 to honor Dr. Martin Luther King, Virginia chose to move Lee-Jackson Day to that same Monday and created Lee-Jackson-King Day.

That unusual mix lasted almost 20 years, until Governor Gilmore convinced the General Assembly to split the holidays. Since 2001, Virginia state employees have enjoyed a 4-day weekend in January. State employees get a Friday off for Lee-Jackson Day, then the following Monday for the Martin Luther King Day holiday.4

In 2010, an action by the governor renewed the debate over whether it is possible to honor Confederates without insulting those who were enslaved in Virginia. Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell declared April to be Confederate History Month in 2010. That was not unusual. However, he omitted the anti-slavery language that had been included by Governor Gilmore in 2001 even though it upset the Virginia Division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy then. The omitted words were:5

- WHEREAS, our generation's recognition of this historical era necessarily acknowledges that the practice of slavery was an affront to man's natural dignity, deprived African-Americans of their God-given inalienable rights, degraded the human spirit and is abhorred and condemned by Virginians, and likewise that had there been no slavery there would have been no war...

McDonnell quickly apologized. The reaction soon died down.

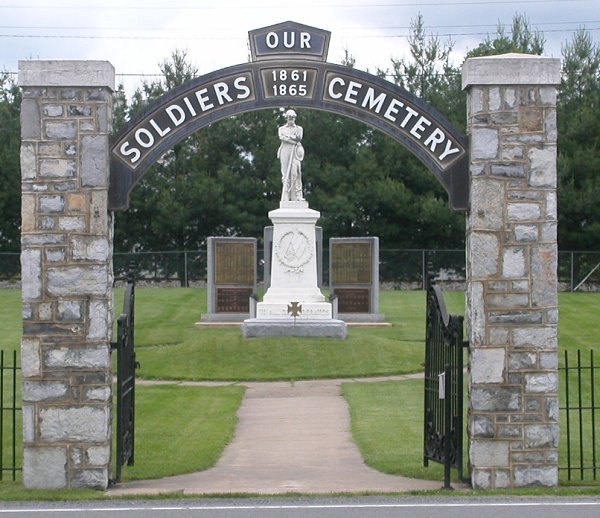

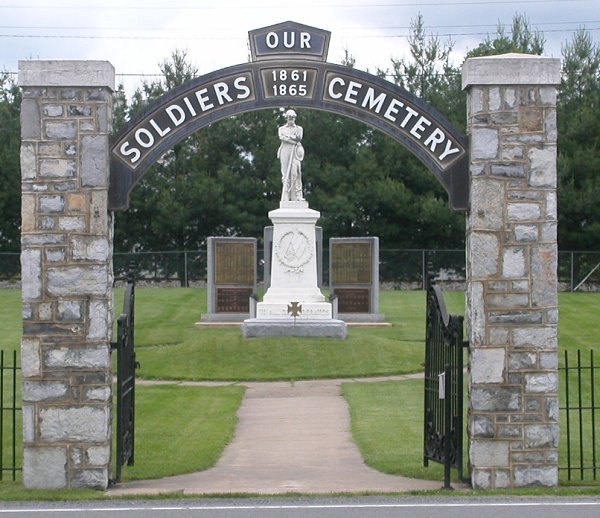

Honoring the Virginians who fought for the Confederacy included veteran reunions until 1951, when the last Confederate Veteran Reunion was held in Norfolk. A decade later, the 100th anniversary of the Civil War (1961-65) occurred at the same time as civil rights movement. Lawsuits triggered changes in once-segregated lunch counters, water fountains, schools, public transportation, restaurants, and even municipal swimming pools.

graveyard near Civil War hospital in Mount Jackson, between Winchester and Staunton

Virginia politicians, led by Senator Harry F. Byrd, threatened "massive resistance" to social changes mandated by Federal courts, the US Congress, and the President. During the civil rights battles in the 1950's and 1960's, the image of a Confederate flag was used to rally opposition to Federal mandates forcing desegregation.

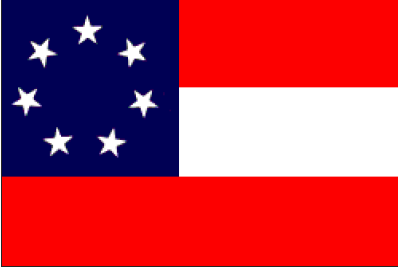

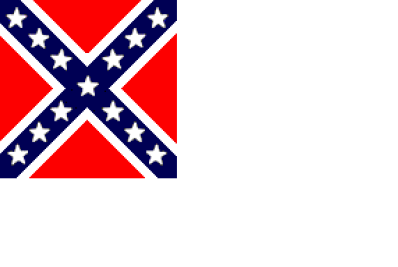

The Ku Klux Klan and other opposed to desegregation adopted a battle flag of the Confederacy as a symbol of "states rights" and opposition to cultural change. For over 50 years, the Confederate Navy Jack has been displayed prominently by some residents of Virginia. Often the owner will refer to it as the "Battle Flag of the Confederacy" or the "Stars and Bars." However, the Army of Northern Virginia, led by Robert E. Lee between 1862-65, carried a square rather than the rectangular version of the flag.6

In 1986, the principal at Fairfax High School eliminated the Confederate symbols traditionally used at the school, including the Johnny Rebel mascot. That shift responded to concerns of the more-diverse student body and parents of students, but also spurred complaints from alumni. The nickname of "Rebels" was retained, and the street leading past the school has remained Rebel Run.7

Fairfax High School is still located on Rebel Run

More recently, bumper stickers with that flag have begun to include the phrase "Heritage, not Hate." This attempts to separate the racial and historical implications of the flag, though the emotional impact of the symbol still blocks many people from appreciating the distinction. Others note that the key state's right underlying the formation of Confederacy was the state's right to preserve slavery, and consider the display of the symbol to be an endorsement of slavery even if the focus is on heritage and not hate.

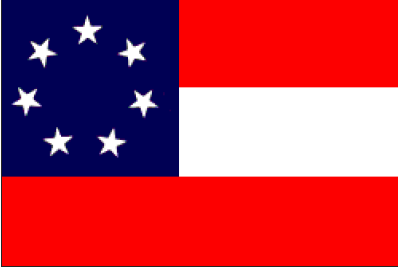

first National Flag of the Confederacy, with only 7 stars (reflecting the number of states that seceded by March, 1861)

Source: National Park Service, Flags of Fort Sumter |

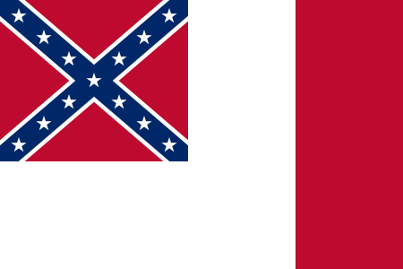

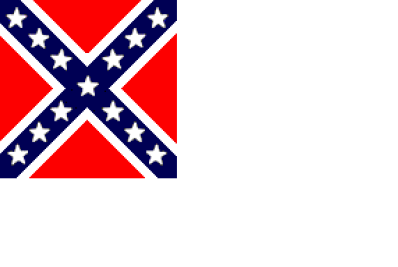

second National Flag of the Confederacy, the Stainless Banner (with a confusing white section that resembled a surrender flag)

Source: National Park Service, Flags of Fort Sumter |

| |

In 1999, the General Assembly authorized a new license plate to honor the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV), but blocked the use of a logo showing the Confederate flag. License plates approved for other groups included a logo as well as the group's name, so the SCV filed a lawsuit. A Roanoke judge ruled that the Commonwealth of Virginia government could not discriminate against the group, and the Fourth Circuit Federal Court of Appeals upheld the decision.

Many Virginians might disagree strongly with what the SCV choose to say, or how they say it, but the court ruled that the state government had no right to discriminate against the Confederate symbol or the group. The Chief Judge of the Federal court said:8

- The Virginia General Assembly has approved over one hundred special plates, and the statute authorizing the SCV special plate is the only one with design and logo restrictions. When a legislative majority singles out a minority viewpoint in such pointed fashion, free speech values cannot help but be implicated. And it is as a free speech case, not as a Confederate flag case, that this appeal must be resolved...

- [T]he First Amendment was not written for the vast majority of Virginians. It belongs to a single minority of one. It is easy enough for us as judges to uphold expression with which we personally agree, or speech we know will meet with general approbation. Yet pleasing speech is not the kind that needs protection.

- Our Constitution safeguards contrarian speech for several reasons. As the Civil Rights Movement demonstrates, yesterday's protest can become tomorrow's law and wisdom. Other contrarian speech should move popular majorities to reaffirm their own beliefs rather than suppress those of others. The reminders of history's most tragic errors only deepen our commitment to the dignity of all citizens: The Constitution that houses the First Amendment also shelters the Fourteenth, an everlasting reminder that a nation betrothed to liberty and equal justice under law must remain vigilant to realize both.

The City of Lexington, where Stonewall Jackson is buried, became the focal point for the "fly the flag" fight in 2010. Traditionally, non-government groups could get permission from the city to display their banners on city-owned light poles in the downtown area. In 2011, the City Council in Lexington decided to stop displaying the Confederate flag. The local city council passed an ordinance to display only the American flag, the flag of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the city flag of Lexington.

Battle Flag with thirteen stars, used by Army of Northern Virginia starting in 1862

Source: National Park Service, Antietam National Battlefield, For the Colors

The Sons of Confederate Veterans sued, contending the city was infringing on its rights of free speech by denying it the traditional opportunity to fly Confederate symbols from the light poles. In 2012, a US District court judged ruled that the city had the legal authority to limit use of its light poles, since:9

- The ordinance is content neutral because it makes no distinction as to viewpoint or subject matter and advances no particular position. Rather, on its face, the ordinance prohibits the expression of all private viewpoints and instead reserves government flag poles for government flags. No private entity may attach its flag to the City s flag poles. There is simply no question that the ordinance does not regulate expression on the basis of content.

Sons of Confederate Veterans license plate

The 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the decision, and the SCV lacked the resources to appeal further to the U.S. Supreme Court. The attorney for the group claimed the decision to block all non-government groups from using the flagpoles as a public form was comparable to closing public schools in order to keep from integrating them. That was a conscious attempt to link the struggle for civil rights and school desegregation during the 1960's to the SCV's struggle to display a symbol of the Confederate government that sought to perpetuate slavery a century earlier.10

However you view the issue, you can get a clue to the culture of a neighborhood by observing if there are Confederate flags flying in public. To understand the cultural geography of an entire area, however, you may have to do more than make a snap judgment based on one house flying a flag.

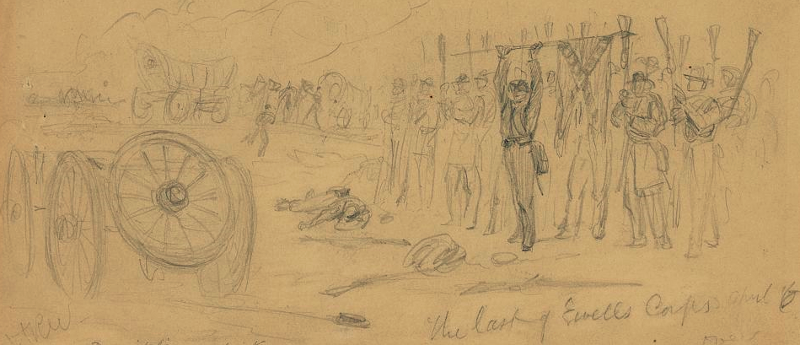

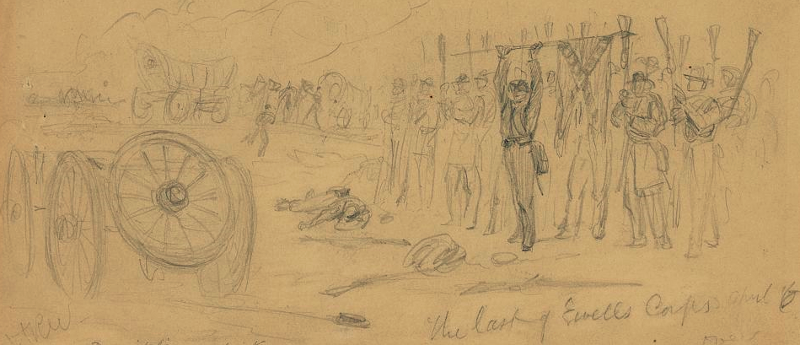

surrender of Confederate flag by Ewells corps on April 6, 1865

Source: Library of Congress, The last of Ewells corps April 6

Links

2013 exhibition of Confederate flag seized by Union troops from Marshall House in Alexandria (May 24, 1861)

Source: New York History blog, NYS Museum Displays Massive Civil War Flag

References

1. Edward Waterhouse, A Declaration of the State of the Colonie and Affaires in Virginia, 1622, in "The Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 8. Virginia Records Manuscripts. 1606-1737," Library of Congress, http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=mtj8&fileName=mtj8pagevc03.db&recNum=572; J. Frederick Fausz, "The First Act of Terrorism in English America," History News Network, January 16, 2006, http://hnn.us/article/19085 (last checked October 9, 2013)

2. J. Frederick Fausz, "The First Act of Terrorism in English America," History News Network, January 11, 2006, http://hnn.us/article/19085 (last checked October 9, 2013)

3. 1998 Strategic Assessment: Engaging Power for Peace, National Defense University, January 1, 1998, http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Chapter+eleven%3A+asymmetric+threats.-a0126790969 (last checked October 9, 2013)

4. "Lee Jackson Day in United States," Timeanddate.com, http://www.timeanddate.com/holidays/us/lee-jackson-day (last checked October 9, 2013)

5. "McDonnell's Confederate History Month proclamation irks civil rights leaders," Washington Post, April 7, 2010, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/04/06/AR2010040604416.html; "Gilmore Eviscerates 'Confederate History Month' In The Old Dominion," United Daughters of the Confederacy, March 21, 2001, http://vaudc.org/evisceration.html (last checked October 12, 2012)

6. "Flags of Fort Sumter," National Park Service, http://www.nps.gov/fosu/planyourvisit/upload/Flags_of_Fort_Sumter.pdf (last checked October 12, 2012)

7. "Fairfax High says goodbye to rebel mascot," United Press International (UPI), February 5, 1986, http://www.upi.com/Archives/1986/02/05/Fairfax-High-says-goodbye-to-rebel-mascot/1229507963600/ (last checked September 2, 2016)

8. Sons of Confederate Veterans vs. Commissioner of the Virginia Department of Motor Vehicles, 305 F.3d 241, United States Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit, September 20, 2002, http://bulk.resource.org/courts.gov/c/F3/305/305.F3d.241.01-1242.html (last checked October 12, 2012)

9. Sons of Confederate Veterans vs. City of Lexington, june 14, 2012, http://www.vawd.uscourts.gov/OPINIONS/WILSON/712CV00013.PDF (last checked October 12, 2012)

10. "Lexington Confederate flag flap discussion continues," The Roanoke Times, December 31, 2013, http://www.roanoke.com/news/article_c72328fc-7293-11e3-8d93-0019bb30f31a.html (last checked January 2, 2014)

final reunion of the United Confederate Veterans in Norfolk, 1951

Source: Norfolk Public Library

The Military in Virginia

Virginia Places