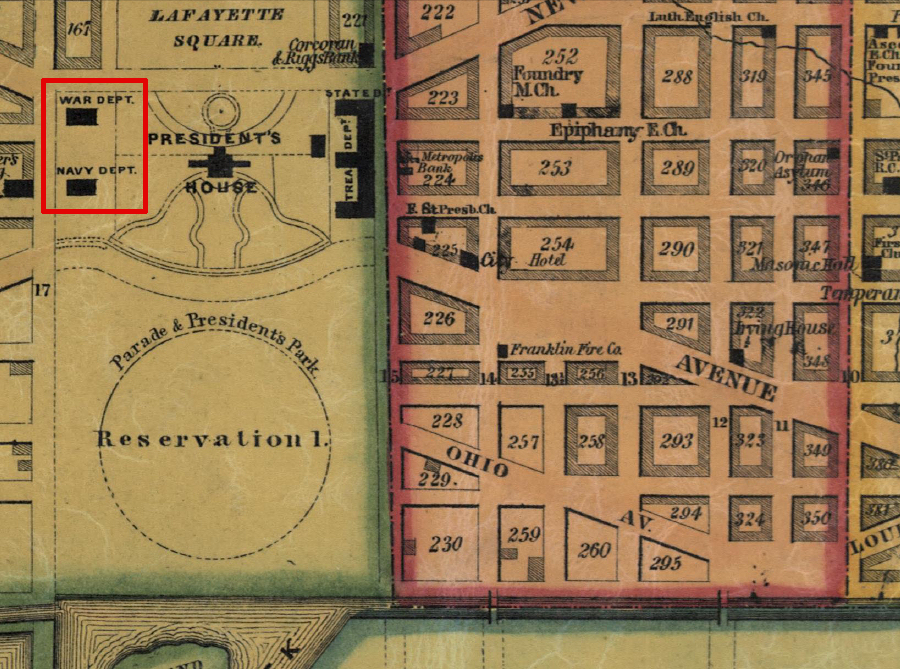

the War Department and the Navy Department occupied separate buildings next to the White House from 1819-1879

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the city of Washington D.C

the War Department and the Navy Department occupied separate buildings next to the White House from 1819-1879

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the city of Washington D.C

When the Federal government moved to Washington, DC in 1800, the Navy and War departments moved into two different buildings located on Pennsylvania Avenue between 21st and 22nd Streets NW. They remained separate departments until creation of the Department of Defense in 1947, and used separate buildings for separate headquarters for much of that time.

The Navy initially occupied one of the "Six Buildings" on the north side of Pennsylvania Avenue. They were privately-owned buildings that were occupied by various Federal offices that could not be squeezed into the Treasury Department Building next to the White House. The Army moved into a building on the south side of the street, but a fire on November 8, 1800 destroyed the building and all the War Department records.1

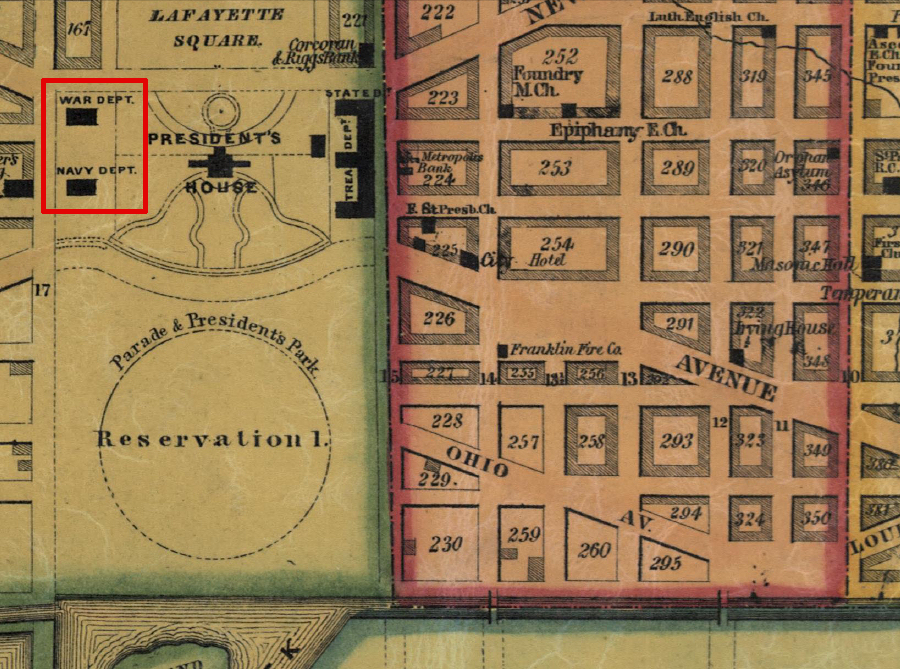

the Navy Department headquarters was in one of the "Six Buildings" (a seventh on the far right was later added) on Pennsylvania Avenue

Source: US Army Center of Military History, Secretaries of War and Secretaries of the Army (p.10)

Soon after President James Madison was inaugurated in 1801, a second major building comparable to the Treasury Department was completed on the southwest side of the White House. It was constructed parallel to the Treasury Department, on the southeast side. Both the Army and Navy relocated to the new public building, as did the State Department.

On August 24, 1814, the British occupied Washington and burned that public building, as well as the Executive Mansion and the Treasury Department building. This time, the War Department lost few records in the fire, having removed them in advance after recognizing the British would occupy the capital.2

The walls of the two-story brick building survived the fire. By 1816, it had been reconstructed and was occupied again by the War, Navy, and State departments. Space was tight, and in 1819, the State Department and War Department moved out. The State Department moved into its own new building northeast of the White House, north of the Treasury Department building.

the War Department moved in 1819 to a two-story brick office with an Ionic portico facing Pennsylvania Avenue

Source: US Army Center of Military History, Secretaries of War and Secretaries of the Army (p.11)

The War Department moved into a comparable structure northwest of the White House, north of its old location where the Navy Department remained in the Southwest Executive Building. It also occupied the Winder Building across the street after it completion in 1848.

During the Civil War, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton added two floors to the War Department building. Abraham Lincoln would walk over from the White House to get updates from the War Department telegraph operators in the Army's headquarters.3

after 1862, the War Department building was four stories tall

Source: New York Public Library, National and Metropolitan Scenery, Washington, D.C. (sometime between 1865-1885) and The War Department, Washington, D.C (sometime between 1864-1871)

The Navy Department also added two floors to its separate headquarters, south of the War Department's building.

the Navy Department expanded its headquarters during the Civil War to a four-story building, comparable to the War Department expansion

Source: Library of Congress, The U.S. Navy Department, 17th St. near Pa. Ave. (between 1867-69)

In 1870, the US Congress decided to construct a new building west of the White House to house the State War, and Navy departments. The new State, War, and Navy Building was constructed in stages. After the War and Navy departments moved into a portion of the new building in 1879, their old homes (known then as the Northwest Executive Building and Southwest Executive Building) were demolished to make room for the rest of what is known today as the Dwight D. Eisenhower Executive Office Building.

Six of the 35-foot high sandstone columns at the War Department building were transported to Arlington National Cemetery. Four were installed at the Sheridan Gate, to create a more-impressive entrance to the cemetery. The other two columns were placed at the north entrance gate, which was later named after Union generals Edward Ord and Godfrey Weitzel. The columns were removed in the 1970's when the entrances were expanded. When the Ord and Weitzel Gate was restored in 2022, those two columns wre re-installed.4

area where the Pentagon would be located, in 1878

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of fifteen miles around Washington (by G. M. Hopkins, 1878)

when the 1820 War Department was demolished, two 35-foot high columns were transported to the north entrance gate at Arlington Memorial Cemetery

Source: Library of Congress, The Ord-Weitzel Gate, Arlington, Va

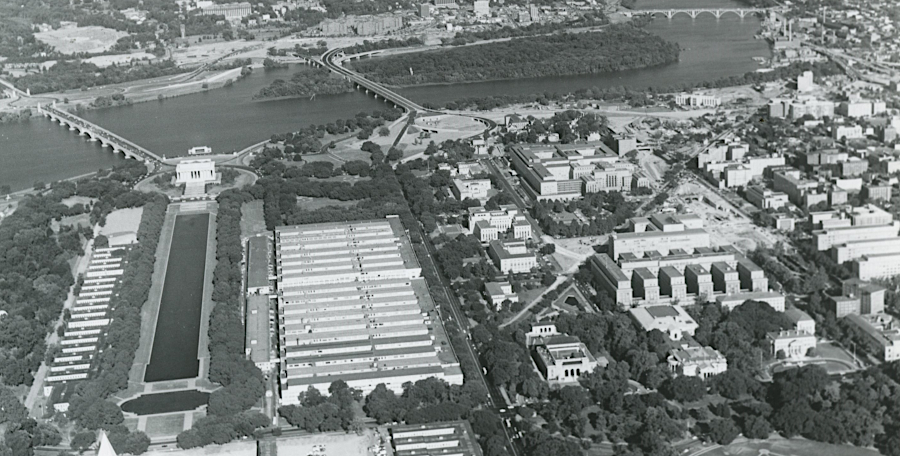

After World War I, the Navy Department left the State, War, and Navy Building. In 1918, the Navy built a "temporary" Main Navy Building on the Mall, with nine wings to house all the officers, staff, and civilian workers at headquarters. The War Department built an eight-wing "temporary" Munitions Building next door. When completed, the structures filled the south side of Constitution Avenue from 17th Street to 21st Street (now the site of Constitution Gardens).5

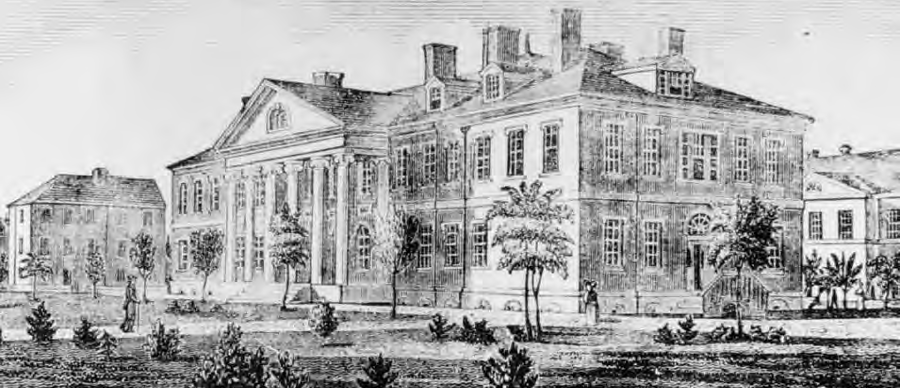

the Main Navy Building (foreground) and the War Department's Munitions Building were constructed in 1918, along with the Reflecting Pool in front of the Lincoln Memorial

Source: Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 2502 "Main Navy" and "Munitions" Buildings

Most offices of the War Department moved to the Munitions Building in 1930, and Congress renamed the State, War, and Navy Building as the "Department of State Building." The office of the General of the Armies of the United States remained in the Department of State Building, until it finally moved to the Munitions Building in 1938.

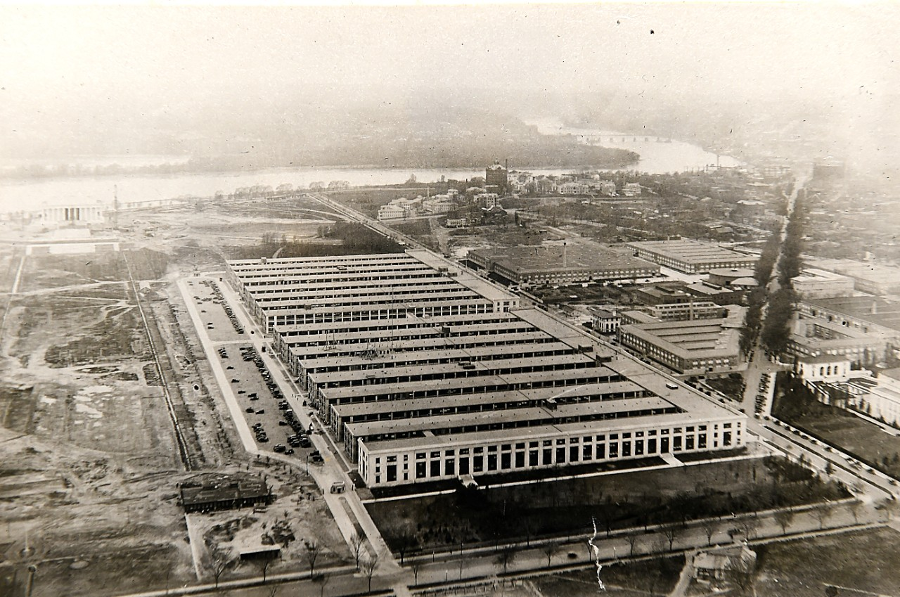

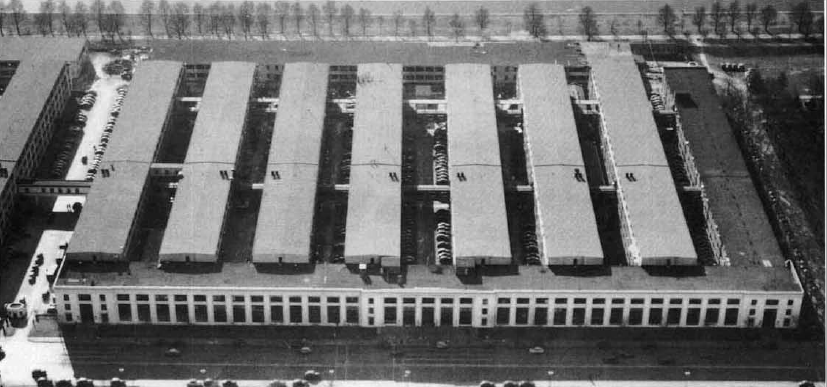

the Munitions Building housed the War Department headquarters between 1938-41

Source: US Army Center of Military History, Secretaries of War and Secretaries of the Army (p.14)

the Munitions Building at 20th Street and Constitution Avenue (Reflecting Pool at top of photo)

Source: The Pentagon: The First Fifty Years (p.8)

The Main Navy Building and the Munitions Building were long-lived rather than temporary.

National Mall in World War II, showing the "temporary" buildings and Memorial Bridge over the Potomac River

Source: National Park Service, HPC_001930 and District of Columbia Department of Transportation, DDOT Historic Collections - Bridges (Roosevelt Island 015)

Those 1918 structures were finally demolished in 1970. Constitution Gardens, with a pool and landscaped knolls, was constructed on their site.6

in 1938, the War Department moved its headquarters from the State, War, and Navy Building next to the White House to the Munitions Building next to the Reflecting Pool

Source: National Park Service, 'Temporary' War Department Buildings

After President Roosevelt was elected to a second term in 1936, he struggled with an isolationist electorate and his concerns about the rise of Nazi Germany. British purchases of war goods helped revive the American economy, and Roosevelt sought to expand the Army and Navy in order to prepare for a future conflict.

The Munitions Building was not large enough to house ever-expanding Army staff overseeing mobilization and preparing options for an American response to European conflict. The War Department arranged for construction of a new building west of the White House at 21st and C Street NW, in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood of Washington, DC. That location was just two blocks away from the Munitions Building.

some War Department offices moved to a new buildng in Foggy Bottom at the start of World War II, but the Harry S Truman Building is now headquarters for the State Department

Source: Wikipedia, Harry S Truman Building

After Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson visited the new building near the end of construction in April, 1941, he decided that it still would be too small. He needed an additional, larger structure to consolidate the 24,000 workers in offices scattered among 17 separate sites plus the 10,000 or more new workers he anticipated hiring in response to the war in Europe.

Secretary Stimson was considering just the requirements of the US Army for space. In 1941, the US Navy was a separate Department. It planned to expand beyond its headquarters in the Main Navy Building, but not to build a new headquarters. The Navy planned to take over the Munitions Building next door, once the US Army left that structure.

Stimson and Roosevelt decided the solution to the office space problem was to move some Army offices into the Foggy Bottom buiilding, and also build a new headquarters for the War Department in Virginia. The Federal government owned large tracts along the Potomac River waterfront acquired during the Civil War, when the Union Army seized the Custis-Lee Mansion and Arlington estate of the family of Confederate General Robert E. Lee.7

The new building intended to house the War Department in Foggy Bottom is now part of the US State Department's headquarters. The new structure to house the War Department, built across the Potomac River in Virginia, became known as the Pentagon.

After the US Congress passed the National Security Act of 1947, the Pentagon became the headquarters for the first consolidated Department of Defense in the history of the United States. The secretaries of the Navy and Army lost their status as members of the President's cabinet overseeing separate Departments, and became subordinate to a new Secretary of Defense. The Air Force became a separate agency, and the Navy was forced to move its headquarters from the Main Navy Building on Constitution Avenue to the same building as the Army and Air Force.

Only one of the 54 "temporary" buildings contructed on the Mall for World War I and World War II still stands. The Liberty Loan Building was constructed in 1919. That reinforced concrete building was the headquarters for the Federal program raising money for the military by selling government bonds.8

the structure planned in the 1930's to be the headquarters of the US War Department is now part of the State Department's headquarters building in Foggy Bottom

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online