Governor Harvey tried to shift colonists towards products other than tobacco, but instead he was "thrust out" and sent back to England

Source: National Park Service, Jamestown, 1630s: Harvey's Industrial Enclave (painting by Keith Rocco)

Governor Harvey tried to shift colonists towards products other than tobacco, but instead he was "thrust out" and sent back to England

Source: National Park Service, Jamestown, 1630s: Harvey's Industrial Enclave (painting by Keith Rocco)

Bacon's Rebellion in 1676 was not the first time Virginians had resisted authority from London, inspired by a desire to acquire lands occupied by Native Americans. In 1635, almost 40 years earlier, Governor Harvey had been placed under house arrest by the key leaders in Jamestown. The royal governor who had been appointed by Charles I was "thrust out," removed from office and sent back to England against his will.

Governor Harvey had made enemies because he refused to issue new grants of land in Virginia. King Charles I was considering a request to re-issue a charter to the London Company, undoing James I's decision in 1624 to revoke the 1612 charter and make Virginia a royal colony. Land grants were halted until vacillating Charles I could establish his own authority by cutting deals with his nobles. In the meantime, Virginians feared that their existing land claims would be voided, as had happened in Ireland.

Governor Harvey had also followed his instructions to support the new colony of Maryland, after the first Catholics arrived in 1634 on the Ark and Dove and settled at St. Mary's on the Potomac River.

The Virginia colonists strongly opposed the loss of "their land" by the creation of the Maryland colony. William Claiborne refused to surrender his claim to Kent Island, citing his grants from Virginia while hoping to maintain a profitable fur trade with the Susquehannocks. After Lord Calvert had one of Claiborne's trading vessels seized, three Virginians were killed trying to recover it. Harvey supported his fellow royal governor rather than the key members of the Virginia General Assembly. Democratic government in Virginia dated back only to 1619, but in 1634 the colonial leaders still forced the royal governor to sail home to England.1

The members of the governor's Council of State saw ownership of land as the vehicle for achieving respected social status, in addition to personal wealth. Travel from England to Virginia across the Atlantic Ocean was dangerous, living far from the comforts of home was harsh - but it was worth it, to achieve a position in society that would have been impossible in England. Any decision by royal officials that stood in the way of the colonists' hunger for land generated a strong response.

The settlers also felt that Governor Harvey had not been aggressive enough against the Native Americans. Opechancanough and his allies had been suppressed since the uprising in 1622, but the cost of warfare was still substantial. Governor Harvey sought to minimize the cost of warfare, but his caution limited the colonists' ability to acquire land occupied by Native Americans:1

King Charles I Sent Governor Harvey back to Virginia to assert his authority, but soon recalled him. The king soon was embroiled in a civil war with Puritans in England, and was executed in 1649.

His son was restored to the throne in 1660 at the end of the English Civil War. Charles II and Parliament passed the Navigation Acts of 1660-63, expanding on the Navigation Act passed in 1651. Those laws blocked the tobacco planters in Virginia from selling directly to customers in Europe (primarily France), and Dutch ships were prohibited from trading with Virginia.

English merchants gained a monopoly, with easy profits as unchallenged middlemen in the tobacco trade. After French and Dutch competition was blocked, Virginia tobacco farmers received lower prices.

The Navigation Acts were based on the economic philosophy of "mercantilism." The assumption was that a positive balance of trade would increase England's wealth and military power compared to rival nations in Europe.

In the 1550's Spain had followed the alternative economic theory of "bullionism," where increased acquisition of gold/silver was expected to enrich a nation. Most of the bullion acquired from Mexico and Peru was used to purchase textiles and other goods manufactured in other countries, and they grew in wealth while Spain's economy lagged. The New World ultimately enriched Spain's rivals, the Netherlands and England, through trade.

Spain's rulers also used the wealth to finance wars in Europe, but then borrowed even more money. Spain's armies failed in their efforts to dominate the continent, and Spain's Armada was equally unsuccessful when it attacked England in 1588. England adopted mercantilism in part because Virginia and other colonies did not provide the gold and silver that Spain's treasure fleets brought back from the Caribbean, and in part because its experience with trade and manufacturing had been successful.

There were two sides in the English Civil War, but both thought that England should receive most of the benefits from its colonies. The Puritans passed the first Navigation Act in 1651 to eliminate Dutch competition in colonial trade, requiring that imports to England be transported in English ships. Charles II supported the Navigation Acts of 1660-63.

The barriers to Dutch trade triggered three separate Anglo-Dutch wars. In 1655, the Dutch seized the Swedish colony at what today is Wilmington, Delaware. The Dutch expanded their foothold in North America, and then lost it.

In 1664, during the Second Anglo-Dutch War, England forced the Dutch to cede New Amsterdam and it was renamed New York. In 1667, Dutch raiders burned six tobacco ships in the James River. In 1673, during the Third Anglo-Dutch war, Dutch warships again succeeded in capturing and burning Virginia merchant vessels with tobacco for export.

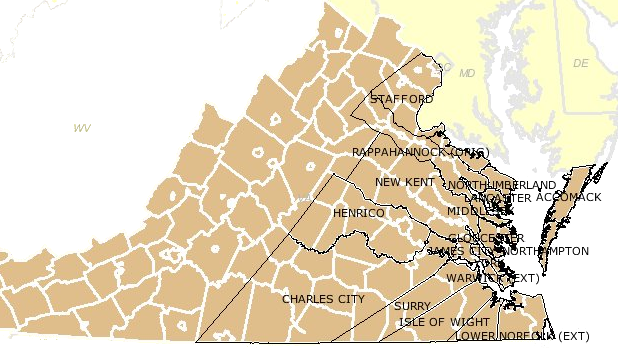

county boundaries in 1676, as settlement extended deeper into Native American lands

Source: Newberry Library Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

Throughout the 1660's, tobacco prices were painfully low and Virginia planters struggled economically. In the trade-only-with-the-home-country approach, England used its colonies as a captive market for exports and prohibited sale of raw materials to non-English customers. Virginia colonists got paid less for tobacco and paid higher prices for the goods transported across the Atlantic Ocean.

The Navigation Acts led to political instability in Virginia. The costs of producing tobacco remained too high compared to the prices paid for the annual crops, despite the General Assembly's legalization slavery and its low-cost labor.

there was no political outlet for the unhappy planters. Governor William Berkeley co-opted the gentry on the Council, and avoided calling a new election for the House of Burgesses between 1661-1676. That left no peaceful option for venting political and economic frustrations.

Part of those frustrations were relationships with the Native Americans.

After the 1644 uprising led by Opechancanough failed, the Algonquian-speaking tribes once controlled by Powhatan were defeated. The colonists imposed the Treaty of 1646 on the Native Americans remaining east of the Fall line in the James River, York, and Rappahannock watersheds. That treaty defined friendly, or "tributary," Native Americans and required them to fight together with the colonists against raiding groups from other tribes.

However, other Native American groups remained powerful and in control of lands north of Potomac/Aquia creeks and west of the Fall Line. As the English pushed further inland, across the Fall Line and away from the Algonquians and the Tidewater rivers, the colonists came into conflict with the Siouan-speaking and Iroquois-speaking tribes.

In 1656, a Siouan-speaking group (known by various names, including Massahocks, Richahercrians/Rickohockans, Mahocks and Nahyssans/Nessans - perhaps Manahoacs moving away from raids of the Iroquois) moved to the James River just above the Fall Line.

In accordance with the Treaty of 1646, the Pamunkeys fought as allies of the colonists in the Battle of Bloody Run on the eastern edge of modern-day Richmond. Chief Totopotomoy of the Pamunkey tribe was killed after the English withdrew from battle prematurely. Nonetheless, the Virginians still refused to trust even the tributary tribes, and on the frontier of the colony it remained easy to blame remaining Native Americans for economic hardship.

Displacing the Iroquois and Siouan-speaking tribes would protect farmers on the frontier, but the Tidewater planters did not want to increase the supply of tobacco when prices were low due to the Navigation Acts. In addition, disrupting the fur trade would not benefit the top tier of Tidewater planters.

the Jamestown elite wanted peaceful trade for furs, but frontier farmers demanded a more-aggressive approach to force Native Americans away from settled areas

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the inhabited part of Canada from the French surveys, with the frontiers of New York and New England (William Faden, 1777)

After the end of the English Civil War and the restoration of Charles II, Governor Berkeley in Virginia sought to minimize the costs of frontier conflict. Like Governor Harvey in the 1630's, he wanted to accommodate rather than fight the Indian tribes in the 1660's.1

Governor Berkeley adopted a defensive strategy, building forts on the frontier. He declined to mobilize an army and try to exterminate any remaining Native Americans on the Coastal Plain, and on the Piedmont between the Fall Line and the Blue Ridge.

Some colonists anticipated that such a war would be a "get rich quick" opportunity. In addition to the seizure of Native American property and land, captured Native Ameicans could be sold as slaves to buyers on Caribbean islands. Governor Berkeley's approach allowed the elite in the colony to retain control over the wealth generated by trading with the Native Americans, and blocked those living on the edge of English settlement from gaining wealth through war.

While Governor Berkeley's strategy avoided the cost of war, the cost of defense was sill high. Local counties were required to pay extra taxes to build the forts and support the "rangers" who patrolled the backcountry. The extra taxes were resented as wasteful. Few residents on the frontier considered static forts and intermittent patrols to provide protection against bands of better-skilled, swift-moving Native American warriors.

the stone basement of the Bel Air plantation in Prince William County may be a remnant of a 1670's fort built as part of Governor Berkeley's defense program

Source: Historic Prince William

Governor Berkeley wanted to avoid another war like 1644 in part because open conflict with the Native Americans would attract unwanted attention in London. The cost of a war would be spread across the colony, not limited to counties where forts were constructed, and the extra taxs would upset the Tidewater planters who dominated the General Assmbly.

England was not expected to send troops to North America, at London's expense, to fight Native Americans. Until the French and Indian War erupted in 1755, frontier defense always required the Virginia colonists to pay higher local taxes to finance the costs of mobilizing the militia and defending the colony. England would finance guard ships in the Chesapeake Bay to limit piracy or attack by anoher European country, but not inland defense.

A full-scale war with Native Americans might force the "naturals" further away from the frontier and facilitate more land speculation as well as colonial settlement, but such a war would require recruitment of colonial troops. More troops might provide military protection for farmers and squatters on the frontier just west of the Fall Line, but Tidewater planters would end up financing the war through extra taxes on titheables.

The economic competition between Tidewater and Piedmont Virginia was becoming clear by the 1660's. The Tidewater gentry did not share the same desire as the relatively poor frontier farmers to open up the Piedmont for settlement.

Though transportation from inland farms to Chesapeake Bay ports was expensive, tobacco grown on small frontier farms in the Piedmont competed with the Tidewater planters' crops. Whenever indentured servants completed their terms of labor and moved to the frontier to start small new farms, that reduced the labor force needed in Tidewater on the large plantations. Worse, the low-quality tobacco grown on the small farms, and shipped via terrible roads to Tidewater wharves, depressed the prices paid for all Virginia tobacco.

Land prices in colonial Virginia were a function of the fundamental supply-and-demand equation of economics. Expanding the frontier westward in the 1670's would increase the quantity of cheap land and increase the amount of poor tobacco grown in the Piedmont, at the expense of those who lived in Tidewater. Paying higher taxes for colonial troops to minimize the Indian threat would reduce the value of the existing plantations along the Virginia coast.

Berkeley refused to react to the claims that the Indians were committing murders and thefts on the frontier. The colonial governor was making a good profit from trading with the Indians, and was not willing to disrupt that business by triggering open war. Governor Berkeley was intimately connected with the Tidewater families. His policies protected their existing wealth rather than encouraged westward expansion.2

As described by Warren Billings:3

The Dutch seizure of New York in 1673, during the third Anglo-Dutch War of Charles II's reign, led indirectly to Bacon's Rebellion. Maryland anticipated that the Dutch might spur the Iroquois in New York to attack the Susquehannocks at the head of the Chesapeake Bay. The Susquehannocks were induced to move close to the friendly-to-the-Maryland-colonists Dogue tribe on Piscataway Creek in the Potomac River watershed.4

Native Americans traveling through the backcountry of Stafford County killed an overseer in 1675. The colonists responded by crossing the Potomac River and killing Susquehannocks as well as Dogues. That initiated a series of raids by Susquehannocks in the backcountry of northern Virginia, but Governor Berkleley still refused to collect an army and eliminate the threat.

In 1676, Nathaniel Bacon accepted the role as leader of the disgruntled settlers. He triggered a civil war in Virginia, one century before the American Revolution, by demanding a military commission that would authorize him to attack the Native Americans.

Bacon claimed to be a champion for those who lived on the frontier and were exposed to the threat of harm by Native Americans. Some who have chronicled Bacon's Rebellion have presented him as a revolutionary seeking liberty, leading Virginians to fight a colonial governor who had turned into a tyrant and cruel reactionary. That approach suggests Virginia colonists took a leadership role in the fight for liberty and freedom a century before the American Revolution started in 1775.

Others suggest Bacon was an opportunist who sought to advance his own chance at wealth and power, and Bacon's Rebellion was an attempt to seize Native American land and sell prisones as slaves. Bacon mobilized poor farmers on the frontier and let them vent their frustrations first by attacking innocent Native Americans, but they were manipulated to serve Bacon's primary objective to take control and replace one set of local elite leaders with another set. The rebellion against the colonial government in 1676 was a coup attempt, not a fight for freedom against tryannical control from London.