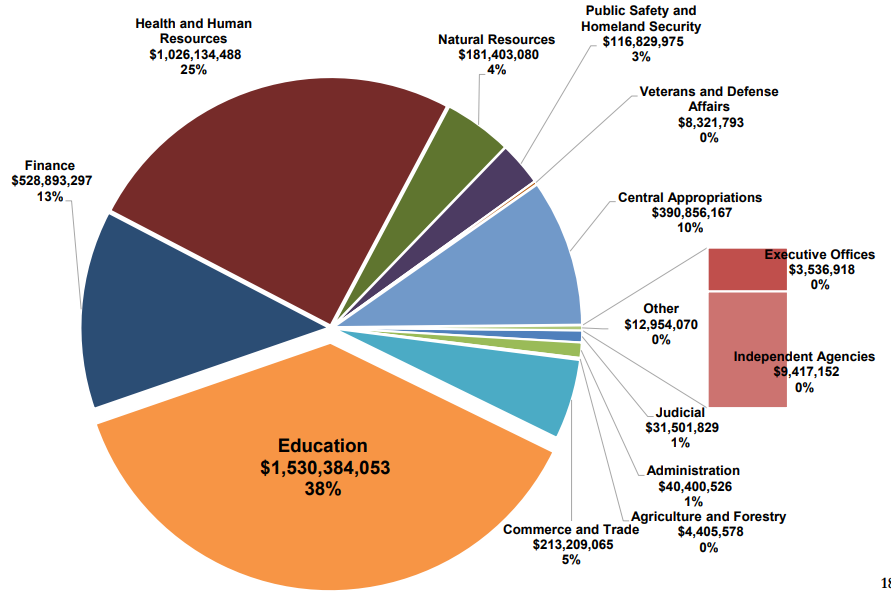

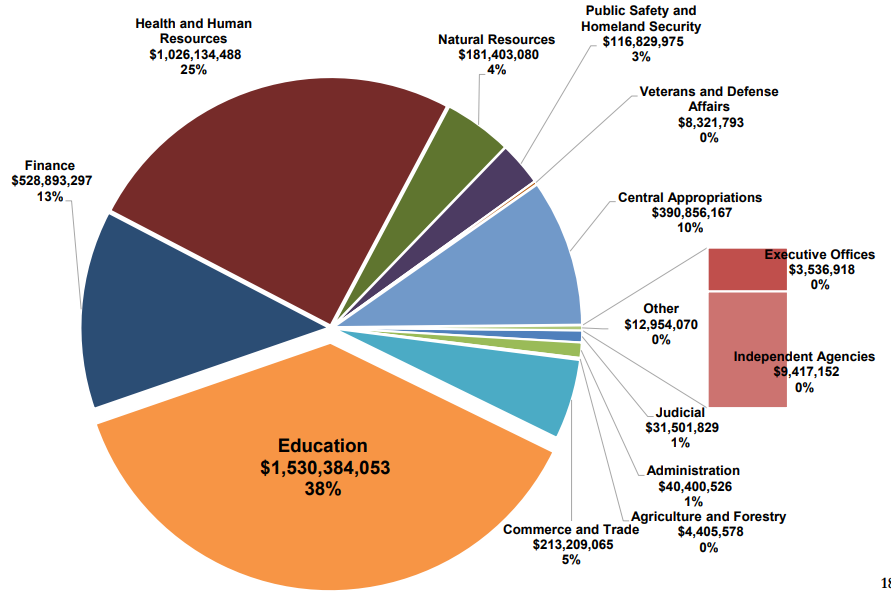

Budget of Virginia

38% of the General Fund portion of the FY20-22 budget was directed to education

Source: Virginia Department of Planning and Budget, Governor Northam's Proposed Amendments to FY 2020 of the 2018-2020 Biennial Budget and the Proposed Biennial Budget for the 2020-2022 Biennium

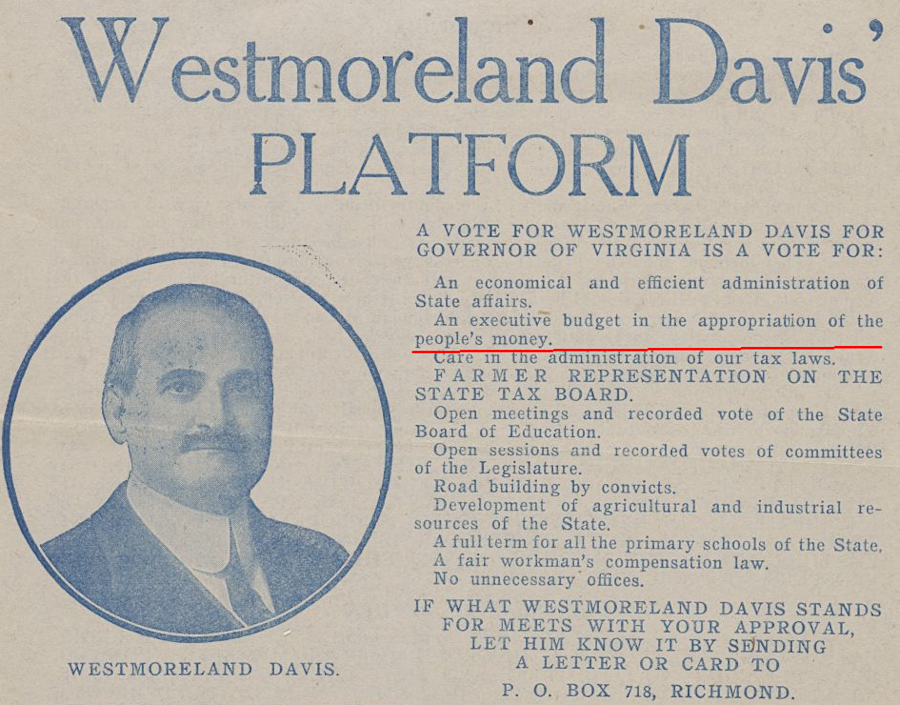

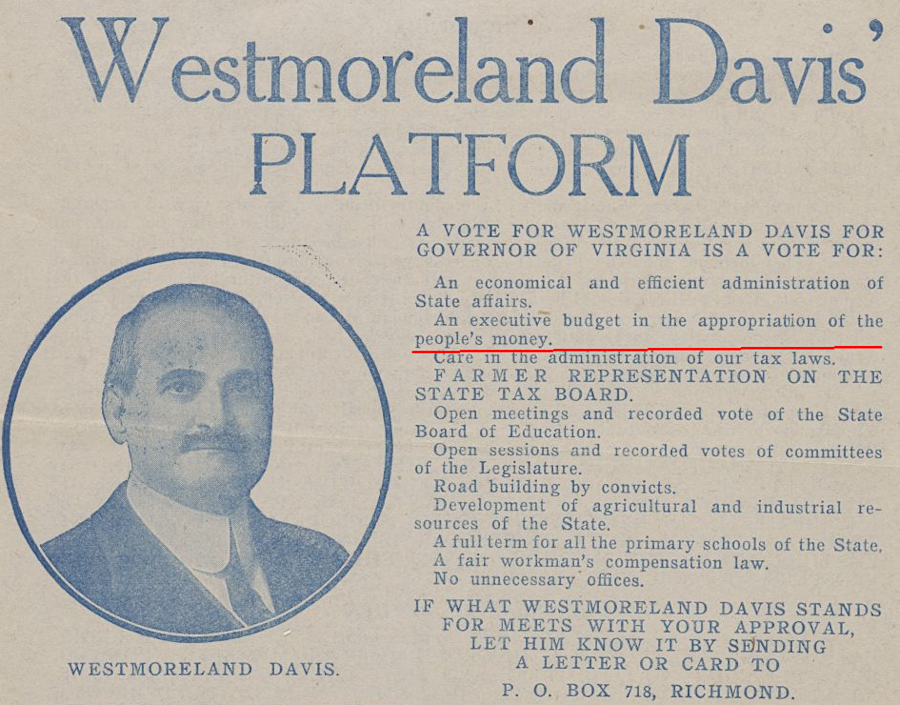

Until 1918, the General Assembly created the state's budget to fund executive branch agencies. The legislature created a study commission in 1916, and it recommended creation of an executive budget prepared by the governor. Westmoreland Davis endorsed the concept when campaigning for governor in 1917. He signed legislation to authorize it in 1918 and submitted the first governor-proposed budget for the 1920-22 biennium.

Westmoreland Davis was elected governor in 1917, and proposed the first executive budget for the 1920-22 biennium

Source: Encyclopedia Virginia, Westmoreland Davis (1859–1942)

The governor's Division of the Budget was created in 1922, using existing state employees assigned temporarily when new budgets were prepared. In 1965, the first permanent professional staff were hired for that office. The Department of Planning and Budget was established in 1976.

In 1983, the State Senate began to draft a budget at the same time as the House of Delegates. Since 1776, the senators had waited until the delegates approved a budget bill. Because that approval came late in the legislative session, senators had limited ability to get their priorities implemented through the budget. The final adopted budget sent to the governor for signature is still a House of Delegates bill, however.1

Two-year budgets are passed by the General Assembly in even-numbered years. The budgets are amended in odd-numbered years with a "caboose bill" to adjust for changes in revenue and priorities. Governors are elected in odd-numbered years, so when they take office the General Assembly is considering a budget prepared by their predecessor. Each governor gets to prepare just one two-year budget that he or she will be able to implement during their term, then prepare a second two-year budget for their successor to implement.

The governor's proposed budget submitted to the 2020 General Assembly was 20% larger than the 2018-20 budget. The budget prepared by Gov. Terry McAuliffe for the 2018-2020 biennium totaled $116 billion.2

A common description of state budgets is that the priorities are to educate, medicate, and incarcerate. State Senator John H. Chichester, president pro tem of the Virginia State Senate, stated in a 2003 speech to the Virginia Foundation for Research and Economic Education:3

- Three quarters of our general fund budget rests in education, Medicaid (which provides health and nursing home care to the poor and elderly), and public safety.

In the 2018-19 budget, over $19 million annually was appropriated for the Office of Education and over $17 million for the Office of Health and Human Resources. Virginia's #3 priority was transportation rather than incarceration. The budget included around $8 million that was allocated to the Office of Transportation and just roughly $3 million annually for the Office of Public Safety and Homeland Security.4

The budget bill is always numbered House Bill 30 and Senate Bill 30. The spending proposed for the next two years by the governor has increased steadily:5

2010 - $77 billion

2012 - $86 billion

2014 - $97 billion

2016 - $109 billion

2018 - $116 billion

2020 - $139 billion

The coronavirus pandemic in 2020 led to extraordinary budget changes within just a month. Governor Ralph Northam declared a public health emergency March 12, the same day the General Assembly passed a $135 billion biennial budget. State finance officials calculated that the pandemic would reduce General Fund revenues by $1 billion in the last months of the FY19-20 fiscal year ending on June 30, 2020, and another $1 billion in the next fiscal year.

Between the time the legislature completed its normal session and the start of the regularly-scheduled veto session on April 22, the governor proposed 180 amendments to the budget. He chose to "unallot" most of the funding increases included in the FY20-22 budget. The unallotting process required state agencies to get specific approval from the General Assembly before they could spend the appropriated-but-not-allotted funding.

The governor also floated the idea that he should be granted authority to reduce spending by more than 15%, the limit allowed without specific approval by the General Assembly. Because the economic situation was so unusual, he also suggested delaying the inevitable revenue reforecast, which was required one tax collections dropped 1% below what had been budgeted the previous fiscal year. Delay would allow more time to assess the problems and opportunities to mitigate them. Though the governor was a Democrat, and Democratic leaders controlled both chambers, the legislators were unwilling to shift that decisionmaking power to the executive branch.6

The governor traditionally proposes a "caboose bill" to amend the budget at the end of the fiscal year. In April 2020, Gov. Northam used the caboose bill to offset the decline in revenues at the end of the 2019-20 fiscal year. The budget had proposed depositing over $600 million in the Revenue Reserve Fund, an optional reserve separate from the Revenue Stabilization Fund ("Rainy Day Fund"). Other savings, such as freezing hires of new personnel, were matched by Federal payments authorized in response to the pandemic. To access Federal contributions for COVID-19 response, the General Assembly approved a budget amendment in April, 2020 to spend $50 million as the state's required matching funds.7

Budget amendments can also be used to propose significant policy initiatives. In 2020, the coronavirus pandemic exploded just after the General Assembly's standard 2020 session had completed work. Governor Northam reacted to the risks of social interaction by proposing, in a budget amendment, to change the date of local elections scheduled for May 5 to align with state elections on November 3. Absentee voting had already begun and candidates were nearing the end of their campaigns when the legislature met on April 22 to consider the governor's vetoes and budget amendments.

Governor Northam vetoed only one bill that session. The legislators had passed HB 119 establishing that plant-based liquids could not be labeled as soy "milk," almond "milk," etc. The veto was upheld, but the State Senate refused to approve the amendment to delay the May vote. Cancelling the May vote would have required discarding absentee ballots which voters had already submitted. Though the House of Delegates approved the delay in a close vote, the State Senate chose not to vote on the proposal and thus blocked the amendment for going into effect.8

According to an opinion by the Attorney General in 2006, the authority of the state to spend money expires on June 30 every two years unless the General Assembly has passed a new budget in the even-numbered years. The 1971 version of the state constitution established a short 30-day "short" session in odd-numbered years and a 60-day "long" session for the General Assembly in even-numbered years. The extra time was expected to be required for passing a budget.

If the state legislators fail to pass a budget or a caboose bill by the end of the regular session, then a special session is called for further debate and final action. Local governments need to know how much state funding they will receive before finalizing their budgets. Any delay by the General Assembly impacts local governments, which typically adopt their budgets in April/May.

In 2006, the final budget was not approved until June 30. In 2022, the General Assembly finished its regular session with an unresolved dispute over $3 billion in the $158 billion budget for 2022-24. Until the Legislative Branch completed a budget in a special session, Governor Youngkin could not propose amendments that reflected his Executive Branch priorities.

Some legal scholars question the concept that the state must shut down on July 1 in even-numbered years if a budget has not been adopted, or a short-term spending resolution has not been approved. In one opinion, essential services could continue because:9

- ...the constitution isn't a suicide pact.

In 2024, both houses of the General Assembly were controlled by the Democrats while the Governor was a Republican. Governor Glenn Youngkin proposed a $63 billion FY25-26 budget with tax cuts, offset by an increase in state sales tax on digital services like music downloads. The legislators sent him a budget with $2.5 billion in extra funding. The governor's proposed tax increase on digital services was expanded, and the tax cuts were cut.

The Democrats incorporated into their budget many different policies and priorities, such as staying in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) market to reduce carbon emissions from electricity generating plants.

The governor considered simply vetoing the entire budget, an act with would require a special session to create a new budget before the end of FY24 on June 30, 2024. Governor Youngkin responded instead with 233 specific budget amendments, reflecting a review of the budget language by his staff which was as detailed as the changes inserted by the Democratic legislators.

The amendments removed all tax increases and dropped the tax cuts, producing a $64 billion proposal.10

The veto session starting on April 17, 2024 had many issues to address in addition to the budget. Of the 1,046 bills sent to the governor, he signed only 75%. In addition to signing 777 bills, Governor Younkin amended 116 and vetoed 153.11

The legislators rejected all of the Governor's budget amendments, creating the potential of a state government shutdown on July 1 if a compromise could not be reached for approval of the FY25-26 biennial budget. Rather than create a political standoff that would put at risk the state's AAA credit rating, the two sides agreed to hold a three-day special General Assembly session in May to produce a new budget.

Ten legislators then negotiated with the governor. A final deal was announced in early May, and the three-day special session was reduced to a one-day event. The deal was announced on the Thursday before the special session opened on the following Monday. The details of the new budget were not made available to the general public until Saturday, 48 hours before the special session.

The Majority Leader of the House of Delegates noted that only 7% of the members of the General Assembly were involved in the decision process. He mentioned the need for members to be briefed after all the budget decisions had been made, because:12

- This budget has significant changes from what we approved, and there's 130 members that don't know what's in it.

The legislators evidently were satisfied with what they learned. The new budget was approved by a 94-6 vote in the House of Delegates and a 39-1 vote in the State Senate. Governor Youngkin signed it the same day, saying:13

- We had a robust discussion around all aspects of the budget... If we know that everyone is not happy then we probably landed in a good spot.

In the final deal, Democrats used $545 million in higher-than-expected state revenue to fund their priorities. That allowed them to remove a proposed new sales tax on digital services. The new tax would have been a deal-breaker for Governor Youngkin, and potentially a justification for vetoing the budget. The compromise FY25-26 budget also eliminated language which Democrats had adopted requiring the state to rejoin the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). That issue would have to be resolved through a lawsuit rather than through the budget.

Major policy issues inserted into the budget by the governor through his proposed amendments were dropped. The deletion of those amendments forced Governor Youngkin to veto or accept bills that he was trying to change, such as the legislature's authorization of skill games which expanded gambling into convenience stores.

The budget deal was approved on a Monday. Governor Youngkin had until Friday to veto other, non-budget bills which he had tried to amend but which the General Assembly had rejected his changes. No public deals regarding the bills were announced before the budget passed, though there may have been some private understandings with Governor Youngkin.

To keep their options open as needed to respond to vetoes, the General Assembly went into recess after approving the budget; it did not formally adjourn. That approach allowed the legislators to reassemble without requiring the governor to call them together.14

Links

- League of Women Voters

- Budget 101 (with Virginia Senator Janet Howell and Virginia House Delegate Vivian Watts, October 14, 2022)

- Virginia Legislative Information System

References

1. "Schapiro: Seeds of budget impasse planted in 1918 and 1983," Richmond Times-Dispatch, February 25, 2023, https://richmond.com/news/state-and-regional/govt-and-politics/schapiro-seeds-of-budget-impasse-planted-in-1918-and-1983/article_acfd1ea4-b458-11ed-b68b-8f0d2928b269.html; "History of Planning and Budgeting Agencies," Department of Planning and Budget, https://dpb.virginia.gov/about/history.cfm (last checked February 25, 2023)

2. Steve Haner, "A 20% Budget Explosion That May Keep Growing," Bacon's Rebellion, January 7, 2020, https://www.baconsrebellion.com/wp/a-20-budget-explosion-that-may-keep-growing/; "Budget Bill - HB1700 (Chapter 854)," Virginia Legislative Information System, https://budget.lis.virginia.gov/bill/2019/1/HB1700/Chapter/ (last checked January 7, 2020)

3. "State-Federal Relations in the Age of Austerity," The Council of State Governments, July 1, 2012, https://knowledgecenter.csg.org/kc/content/state-federal-relations-age-austerity-0; "Guest Column - John H. Chichester," Bacon's Rebellion, August 11, 2003, https://www.baconsrebellion.com/archive/issues/03/08-11/Chichester_speech.htm (last checked August 24, 2019)

4. "Budget Bill - HB1700 (Chapter 854)," Virginia Legislative Information System, https://budget.lis.virginia.gov/bill/2019/1/HB1700/Chapter/ (last checked August 24, 2019)

5. Steve Haner, "The 20% Growth Claim Is Not Misleading," Bacon's Rebellion blog, January 10, 2020, https://www.baconsrebellion.com/wp/the-20-growth-claim-is-not-misleading/ (last checked January 11, 2020)

6. "Northam drops bid to expand power to make spending cuts, as assembly prepares to 'pause' new spending," Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 21, 2020, https://www.richmond.com/news/virginia/northam-drops-bid-to-expand-power-to-make-spending-cuts-as-assembly-prepares-to-pause/article_d9461078-56de-558b-b4ec-bb1c862c5e9e.html (last checked April 21, 2020)

7. Dick Hall-Sizemore, "Stop Gap Budget Amendments," Bacon's Rebellion blog, April 19, 2020, https://www.baconsrebellion.com/wp/stop-gap-budget-amendments/ (last checked April 21, 2020)

8. "HB 119 Milk; definition, misbranding product, prohibition," Virginia Legislative Information System, Virginia General Assembly 2020 Session, https://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?201+sum+HB119; "Senate effectively kills Northam's proposal to move May elections to November; could still be pushed to June," Danville Register & Bee, April 23, 2020, https://www.godanriver.com/news/local/senate-effectively-kills-northams-proposal-to-move-may-elections-to-november-could-still-be-pushed/article_82714bb6-8543-11ea-88db-a30b157485bf.html (last checked April 23, 2020)

9. "Does the General Assembly need longer sessions, or fewer bills?," Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 8, 2022, https://richmond.com/news/state-and-regional/govt-and-politics/does-the-general-assembly-need-longer-sessions-or-fewer-bills/article_61d576a2-3179-5743-88a9-ea760fe2e049.html; "Schapiro: Over time, overtime - time and time again," Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 8, 2022, https://richmond.com/news/state-and-regional/govt-and-politics/schapiro-over-time-overtime---time-and-time-again/article_863267ff-51d2-5f78-a16c-1c8dfb3aeca2.html (last checked April 11, 2022)

10. "Avoiding full veto, Youngkin sends lawmakers 233 budget amendments," Virginia Mercury, April 8, 2024, https://virginiamercury.com/2024/04/08/avoiding-full-veto-youngkin-sends-lawmakers-233-budget-amendments/ (last checked April 9, 2024)

11. "Last batch of Youngkin bill actions circulates at deadline," Virginia Public Media, April 8, 2024, https://www.vpm.org/news/2024-04-08/glenn-youngkin-bill-legislation-deadline-new-virginia-laws (last checked April 9, 2024)

12. "Virginia budget negotiators, Youngkin strike deal on spending plan," Washington Post, May 9, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2024/05/09/virginia-budget-deal-youngkin-general-assembly/ (last checked May 10, 2024)

13. "Virginia lawmakers pass bipartisan budget that leaves tax policy unchanged," Virginia Mercury, May 13, 2024, https://virginiamercury.com/2024/05/13/virginia-lawmakers-pass-bipartisan-budget-that-leaves-tax-policy-unchanged/ (last checked May 14, 2024)

14. "Va. lawmakers avert budget crisis, approve bipartisan spending plan," Washington Post, May 13, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2024/05/13/virginia-budget-youngkin-assembly-taxes/ (last checked May 14, 2024)

Virginia Government and Politics

Virginia Places