Monticello, Thomas Jefferson's home near Charlottesville (Monticello, not Montebello...)

Monticello, Thomas Jefferson's home near Charlottesville (Monticello, not Montebello...)

The "special places" of Virginia could be defined by the places acquired by the government and open to the public as recreational or cultural sites... but the Virginia homes of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, and Woodrow Wilson are privately-owned facilities.

(There is no "official home" for the other US President born in Virginia. Several counties claim Zachary Taylor was born within their borders. The location of his actual birthplace is unclear, but the place cited most often is Montebello in Orange County.)

Where do you go in your leisure time? Do a quick personal inventory of where you went to "recreate" since the semester started - and then calculate who provided those recreational opportunities. Most people participate in a spectrum of recreational activities, and discover that a wide range of private and public organizations provide the support for their "fun times."

Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts

In addition to private clubs, local city and county governments generally provide facilities for "active" recreation - public tennis courts, swimming pools, golf courses, soccer fields, baseball diamonds, etc. Members of local park authorities are usually appointed by city councils and Boards of Supervisors. If you want to experience the responsibilities of being a government official without the hassle of running for office in a political campaign, get appointed to such a board.

Odds are, your phone will start ringing from people with ideas, requests, and complaints. Now that Virginia communities are electing school boards again, candidates may hear from voters who care about the use of the school ballfields (i.e., what fields should get lights first...), even if the voters no longer have children in the local school system.

Communities may combine to form organizations such as the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority, in order to provide recreation opportunities (especially hiking trails, campsites, and lakes for boating) or cultural resources (such as regional museums) that would otherwise be too expensive for one jurisdiction. Occasionally, some Virginia cities who own drinking water reservoirs located at a distance from the city boundaries are able to convince the surrounding county to share the costs for managing recreational use there.

The State Department of Historical Resources lists the historically-significant places in the Virginia Landmarks Register. The National Park Service maintains a list of nationally-significant places in the National Register of Historic Places.

Not all counties are equally represented. Compare the Virginia Landmarks Register listings for Buchanan and Dickenson counties with the listings for Prince William and Loudoun counties - perhaps there's more history in Northern Virginia Another possibility: development in the suburban counties has sensitized residents to changes in the landscape and historical places, creating more public interest in getting historic places protected before they disappear under another subdivision.

The unique places in the DC suburbs could be submerged by cookie-cutter housing developments, if the "special" places are not identified and protected... but in the Appalachian Plateau, is population growing equally fast as in the three urbanized areas of Virginia (Northern Virginia, Richmond, and Hampton Roads)?

The Virginia state park system attracted 4.4 million visits in 1994, but by 2010 had almost doubled visitation to over 8 million visitors.3

Virginia voters have supported new investment in the Virginia State Parks. A $95 million bond issue in 1992 provided funding to upgrade existing facilities and add 4 new state parks. In 2002, Virginians approved borrowing an additional $119 million - and that park bond received nearly 70% of the vote, despite the recent "dot.com" recession.

The 2002 funding allowed development of facilities on lands acquired with the 1992 bonds, as well as purchase of 3 new state parks and 10 new natural areas (plus expansion of 11 parks and 8 preserves). Creative financing allowed the state park system to begin operating Natural Bridge as a state park in 2016, even while the land remained privately owned.4

Natural Bridge became a state park in 2016

Source: Virginia State Parks, Natural Bridge State Park

In 2006, the argument for additional land acquisition for state parks and preserves was articulated by the governor:5

Raising taxes is one way to pay for new parks - but a bond issue is more popular among elected officials. Bond issues are like mortgages. All the money needed to buy land/build facilities is raised when bonds are sold, but repayment is spread over 20 years.

Rosewell, ruins of the Page family plantation (Gloucester County)

Also, look for the state to request Federal assistance. About 9% of Virginia is owned by the Federal government. This includes military bases (open for hunting, in normal times) as well as national parks, national forests, and national wildlife refuges:

The General Assembly and state agencies identify areas that are "special" when compared to the rest of Virginia, and focus state funding on such sites. Local communities have to finance most recreational sites of importance to local taxpayers. Bonds are a popular tool for funding recreation projects at the local, as well as the state level. For example, Stafford County passed an $11 million bond issue for parks and recreational facilities in the November 6, 2001 election (by a 60%-40% landslide). A quick peek at the Census statistics for the county in the year 2000, and you can see the per capita level of debt accepted by each current resident.

Parks for recreational use, and protected natural areas, are not randomly distributed across Virginia. You can see from the map of Statewide Occurrences of Monitored Natural Communities that Virginia has focused on areas along rivers and the coast, plus mountain ridges. There are few sites identified in the Piedmont, between the Roanoke-Rapidan rivers. Also, it's obvious from the map that the caves of Virginia are in the limestone bedrock located west of the Blue Ridge.

Federal agencies seek to protect locations that are uniquely valuable when compared to other locations in the other 49 states. Federal highway bills have provided funding for cultural projects recently, but Federal funding is less accessible for active recreation facilities. Such facilities are used by local residents, rather than by visitors from outside the community. The state and Federal governments consider it the responsibility of local governments to develop as many recreational sites as the local community is willing to finance.

Federal parks, forests, and refuges tend to protect large blocks of land that are more suitable to less-intense recreational activities - hiking, hunting, birdwatching, etc. For example, the Department of the Interior's 2002 budget included $2 million for acquisition of new wildlife refuge lands along the Rappahannock River.

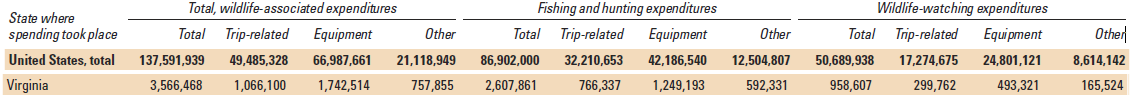

Do the math - between fishing, hunting, and wildlife watching - what outdoor activity generates the greatest economic benefit in Virginia?

The 2011 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation indicated that 14% of Virginia residents 16 years old or older were hunters or anglers, and 36% were "Wildlife-watching participants" (closely observing, photographing, feeding, visiting public areas, and maintaining plantings and natural areas). Hunters and anglers combined outspent wildlife watchers by 2:1 ($2 billion vs. $1 billion), even though there were twice as many people engaged in wildlife watching (2.5 million) compared to hunting/fishing (1.3 million) in Virginia.7

the Rockingham County courthouse in Harrisonburg is an historic structure