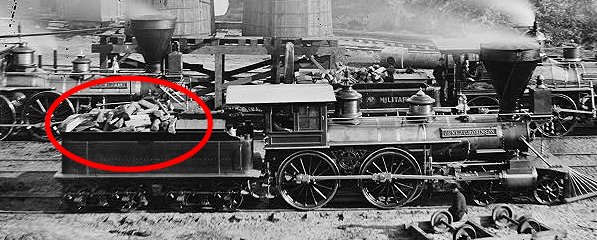

Note the firewood in the tender behind the locomotive

at City Point during the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress

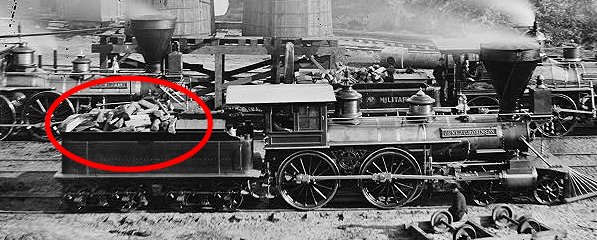

Note the firewood in the tender behind the locomotive

at City Point during the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress

The sailing ships relied on wind power, and nearly all of the locomotives on Virginia railroads relied upon the first fossil fuel - wood - through the Civil War in Virginia. The locomotives on Virginia railroads could rely upon firewood being available all along the rail line, so locomotives could stop and refuel with wood all across Virginia. In contrast, coal was relatively scarce and not widely available for the first 30 years of railroad transportation in the state.

The Virginia forests provided an abundant (and therefore cheap) supply of firewood. Farmers (and their slaves, working to earn cash with permission of the slaveowners) made a profit by cutting and stacking firewood near the railroad tracks in the winter, when there were few other agricultural tasks to perform. There was some coal mined near Richmond prior to the Civil War, but the abundant supplies of coal in western Virginia seams would have to be transported across the state.

Coal is a heavy mineral; a sack of coal is much heavier than a sack of dog food. Transporting coal requires more than just horse and wagon technology. The western Virginia was more expensive until railroad lines were built into the Appalachian Plateau in the 1880's.

Coal was first mined in the Richmond Basin west of Richmond. Thomas Jefferson referred to it in his Notes on the State of Virginia:1

The Richmond Basin is a Triassic Basin, one of the cracks in the earth's surface that formed about 200 million years ago when the continents split apart and the Atlantic Ocean was created. At times there were swamps with lush vegetation in the low places in the Midlothian area of that basin. Some organic material was buried and converted under pressure into bituminous coal. (No coal deposits have been discovered in the Triassic Basin near Manassas, but freshwater limestone was deposited in Loudoun County when lakes formed in the basin.)

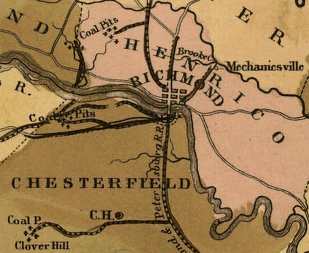

Richmond Basin, site of first Virginia coal mines - formed in Triassic Period

when continent of Pangea cracked, Africa/Europe split off from North America, and Atlantic Ocean formed

(another Triassic basin formed west of Manassas, where basalt lava "dikes" and "sills" are now quarried for gravel used in building/road construction)

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy - Generalized Geologic Map of Virginia

The first railroad in Virginia was built to carry the Triassic-age coal from Midlothian to Richmond. The Chesterfield Railroad was built before locomotives were available - mules pulled the wagons on the rails, before locomotives were perfected. Because the rails reduced friction dramatically, the mule-and-wagon technology for transport was cost effective even before steam locomotives arrived in the 1830's.2

the Midlothian coal beds in Chesterfield County were deposited in the Triassic period between 250 to 200 million years ago

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the internal improvements of Virginia; prepared by C. Crozet, late principal engineer of Va (1848)

The energy source that powered the Industrial Revolution was coal. It was abundant in England, where forests had become scarce since the 1730's. Coal provides substantially more energy per pound of weight or unit of volume than wood or charcoal. In Virginia, coal was slower to replace firewood for powering modern transportation - but steamships could not refuel every thirty miles or so, like locomotives. For ships, coal was clearly superior to carrying a massive load of wood in order to heat steam in a boiler and power a paddlewheel.

Historic signs near Harper's Ferry claim that the steamboat was first invented there. James Rumsey tried to demonstrate a steam-powered boat on the Potomac near Harper's Ferry in 1786, but most people credit Robert Fulton as the inventor of the steamboat because of his successful operations on the Hudson River. It took until 1817 for the first steamship, the Savannah, to cross the Atlantic Ocean - and it used sails as well for energy.

The first commercial ship to use nuclear power was also named the Savannah. After it was decommissioned, the nuclear-powered Savannah was mothballed for years near Newport News as part of the James River Merchant Marine Reserve Fleet.

In the Civil War, the first ironclads were too heavy to be powered by sail; they relied upon steam engines powered by coal. The original wooden USS Merrimack had required 2,800 pounds of coal per hour.3

The Confederates built the CSS Virginia on the hull of the old warship. The far-heavier version of the ship, coated with iron, required even more coal - and was so underpowered that it still needed 40 minutes just to turn around.4

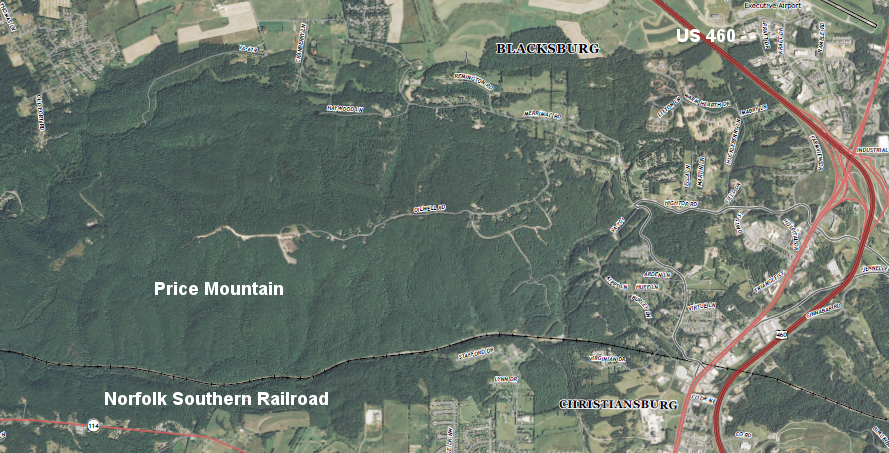

The Merrimac Mine on Price Mountain, halfway between Christiansburg and Blacksburg in Montgomery County, was named because it supposedly supplied the fuel for the Confederate ship. In 1861, the coal from Merrimac Mine could be shipped east on the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad to Lynchburg, then the South Side Railroad to Petersburg, and then the Norfolk and Petersburg railroad to the navy yard where the USS Merrimack was transformed into the CSS Virginia ironclad.

Price Mountain, near Blacksburg

(between I-81 and Virginia Tech, recognizable from US 460 due to communications towers on Price Mountain)

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Blacksburg 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2013, Revision 1)

The coal mines near Richmond were a closer source of fuel for the Confederate ship, but the Triassic Basin mines in Chesterfield County produced soft bituminous coal. The coal at Merrimac Mine in Montgomery County was semi-anthracite.

Anthracite is a harder, more energy-rich form of coal, compressed in part by the continental collisions that uplifted the Appalachian Mountains over 200 million years ago.

Price Mountain is southwest of the Virginia Tech campus, between Blacksburg and Radford

Source: US Geological Survey, Blacksburg 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2011)

West and southwest of Montgomery County, the coal on the Appalachian Plateau in western Virginia was known to exist before the 1880's. Some was used by local residents (primarily for heating a few mountain cabins). However, it was uneconomic to mine before railroads expanded into the coalfields, and carried the coal to industrial sites in Pennsylvania and other northern markets. There were no manufacturing facilities in the mountains that required steam power to justify mining of Appalachian Plateau coal until the railroad arrived.

Even today, with the exception of some coal-fired power plants generating electricity, there are few major local consumers of coal in the Appalachian Plateau of Virginia. Birmingham, Alabama managed to develop an economy with heavy industry that used the local Appalachian coal, but the closest equivalent in Virginia was Low Moor in Alleghany County.

Low Moor is in Alleghany County, between Clifton Forge and Covington

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

The Low Moor Iron Company converted coal into coke, heating it in the absence of oxygen in coke ovens before using the coke in blast ovens. The process of driving off the moisture and concentrating the energy by converting coal into coke was comparable to how wood was converted into charcoal. Coke replaced charcoal as the fuel and "reducing agent" in most Virginia iron furnaces after the Civil War. Before the war, it was not economical to ship coal from the rich beds in the Appalachian Plateau, via wagons over dirt roads, to the iron furnaces.

Mining Virginia coal for export from Appalachia required a cost-effective way to ship the heavy coal from the Virginia mountains to a market. Alexandria merchants financed the Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire railroad (now the W&OD bike trail) in hopes of reaching the Appalachian coal in Hampshire County (now part of West Virginia). The lower Shenandoah Valley farm trade was important, but note that the railroad was not named the Alexandria, Loudoun, and Frederick Railroad.

Alexandria never built a railroad to the coal in northern West Virginia. The Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad - and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal - captured the business and carried the coal from the West Virginia mines in the Potomac River watershed to the cities on the East Coast.

End of the line prior to Civil War: Richmond had a rail line extending west of Staunton to Covington, in Alleghany County

(and note that in 1861, no railroad goes north through the Shenandoah Valley between the James River-Potomac River... yet.

"Bonsacks" is today's Roanoke, and Newbern is near modern-day Christiansburg where Merrimac Mine coal would have been loaded.)

Source: Library of Congress - Map of the seat of war with the lines of r. roads leading thereto, also the strategical points as laid down

During the Civil War, the coal fields of Appalachia were *not* a military objective because neither Union nor Confederate sides were taking advantage of the resource. The salt in Southwestern Virginia was more useful than the coal.

Confederate armies required large quantities of preserved food, and salt preserved beef. It is an old saying that an army may march on its feet, but it fights on its stomach. Saltville was the major source of the basic food preservative for Virginia and other Confederate states between 1861-65.

In 1864, the major conflicts in Southwestern Virginia were over the salt-producing operations at Saltville. There were efforts by the Union Army to cut the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, which carried the salt and other supplies to Confederate forces near Richmond and Petersburg.

The Union Army did succeed in burning the bridge over the New River at Radford after the Battle of Cloyds Mountain, and did disrupt the saltmaking briefly. Union generals did not target Confederate coal operations in Southwestern Virginia in the 1860's, because there were no major coal mines there during the Civil War.

both Saltville and Radford were targets of Union attacks in 1864, in efforts to disrupt the flow of supplies - but not coal - to Confederate forces near Richmond/Petersburg

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

In Southwest Virginia, cheap transportation did not arrive in the mountains until the 1880's. The Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) extended its rail lines west and south of Covington, and the Norfolk and Western (N&W) built rail lines up the New River into the coal fields of what had become West Virginia after 1863.

It took another 15 years after the Civil War before railroad executives invested in building lines into the Southwest Virginia mountains to haul coal to the factories in the North and overseas. The Norfolk and Western targeted the 13' high Pocahontas coal seam in Tazewell County, building a railroad line that went into West Virginia and snaked back to the town that developed around the mine.

1910 advertisement for Pocahontas coal

Source: American Wool and Cotton Reporter

the Pocahontas coal mine, with a seam so high miners had to reach up to excavate "tall coal," is now just a tourist attraction

Once the coal boom came to the mountains, there was a need for coal miners. The local population could not supply a sufficient number of workers, so the coal companies built coal towns and recruited residents from overseas as well as from the Deep South.

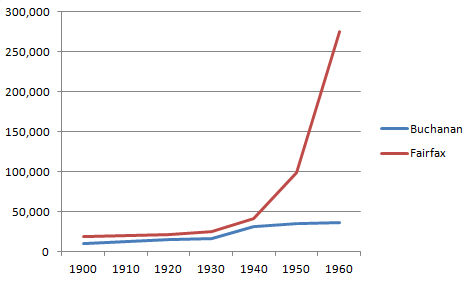

The population of the counties in the Appalachian Plateau of Virginia grew during the coal boom, starting in the 1880's and expanding with demand for coal in World War I and World War II.

The need for workers declined after World War II due to mechanization of the coal mines. At the end of the 20th Century, the population decline in the coal region of Virginia was accelerated after the development of "fracking" made natural gas less expensive than coal for facilities generating electricity.

Buchanan County population tripled between 1900-1950 thanks to demand for coal, rivaling Fairfax County growth until World War Two

Source: University of Virginia, Historical Census Browser