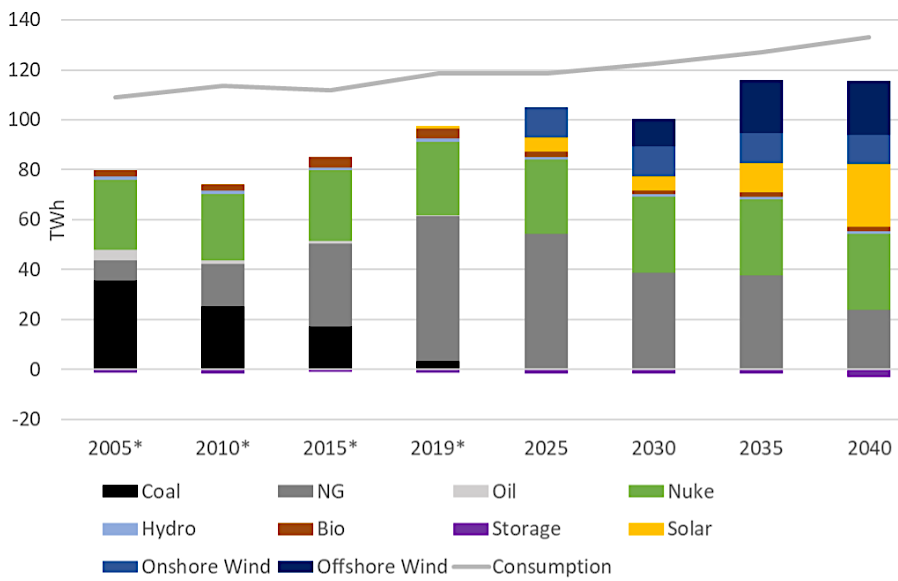

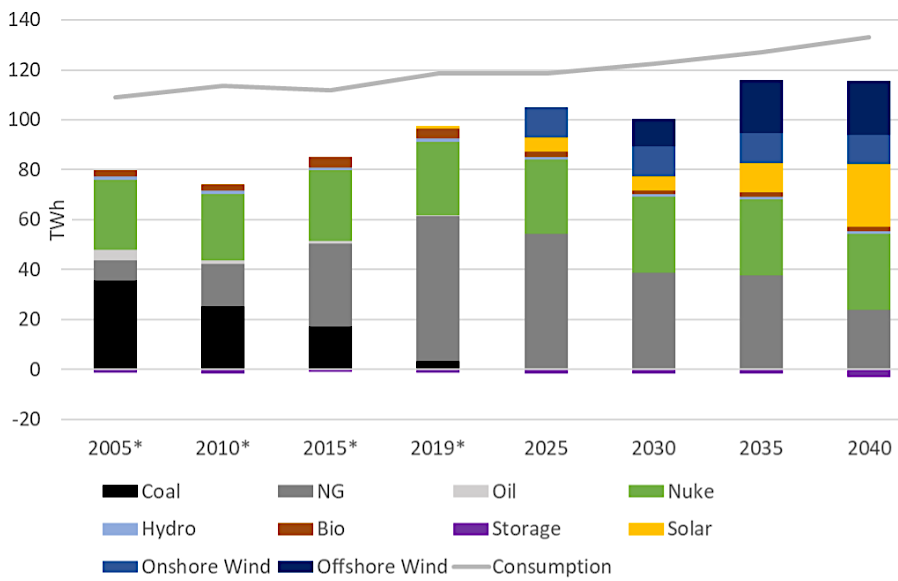

2021 prediction of how Virginia's electricity generation can be carbon-free by 2045

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Illustrated atlas of the city of Richmond, VA (September 9, 2021 Virginia Energy presentation on decarbonization modeling)

2021 prediction of how Virginia's electricity generation can be carbon-free by 2045

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Illustrated atlas of the city of Richmond, VA (September 9, 2021 Virginia Energy presentation on decarbonization modeling)

Virginia is experiencing a dramatic shift in energy production and use. Population growth will require more energy, but the sources of that energy are shifting. The significance of oil for transportation and coal for electricity are dropping.

More-efficient cars are constraining the demand for gasoline, causing transportation officials to complain that the gas tax is not generating enough revenue to build planned projects. Natural gas and renewable energy supplies will supply an increasing percentage of electrical demand.

The future of nuclear energy, which generates no greenhouse gases and provides reliable, low-cost energy, will depend upon the public's tolerance for the safety risks. The public will not support nuclear power if elected officials fail to establish a long-term solution for storage of highly radioactive wastes, and if events such as Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima release more radioactivity. The high cost and high risk could cause the Virginia State Corporation Commission to reject any proposal by Dominion to build a third reactor at the North Anna power plant.

nuclear waste going to Nevada by rail could include trips through Virginia carrying spent fuel rods from plants in southeastern states

Source: Nevada Agency for Nuclear Projects, Nuclear Waste Transportation Routes (1995)

Virginia still depends upon gasoline/diesel to fuel almost 100% of cars/trucks/trains/ships, but the lower cost of natural gas could disrupt the energy side of the transportation sector. Predictions about an inevitable rise in the cost of oil, as the oil industry moves past the peak of production and as developing economies (especially Brazil, China and India) demanded more oil, were overstated at the start of the 21st Century, but the increased supply of natural gas could make Compressed Natural Gas an effective competitor in the transportation sector. Fleets owned by bus and trucking companies are shifting away from diesel, buying vehicles fueled by natural gas and creating re-fueling stations for those fleets.

steam locomotives in Virginia relied upon coal, while today's diesel-electrics use petroleum - and future cars will use electricity

A shift to fuel-efficient cars and electric cars over the next 20 years is reducing demand for gasoline. State and Federal revenues generated from the gas tax are inadequate to maintain and expand the transportation network. In the future, gasoline taxes could be based on miles driven rather than gallons purchased.

As noted the 2010 Virginia Energy Plan, 37% of Virginia households now use natural gas.1

Natural gas requires a complex pipeline distribution system to move energy from Gulf Coast pipelines, coalbed methane fields in Virginia, and new pipelines from the Marcellus/Utica shale gas fields opened up by fracking. Those underground pipelines are gradually aging, increasing the potential for dramatic accidents in the future.

The distribution of gasoline is the most stable aspect of energy in Virginia. Gasoline, shipped from the Gulf Coast through pipelines to Virginia, is stockpiled first at a few bulk storage facilities in every urbanized area. From those terminals, gasoline is distributed through tanker trucks to the 3,361 gas stations scattered across the state in 2013. There is no evident change on the horizon to delivery of refined petroleum products by pipeline, centralized storage/blending at terminals, and decentralized sales at gas stations. The delivery of heating oil to individual homes by trucks will continue.2

Nearly 100% of Virginia households uses electricity, and that is unlikely to change. However, the source of that electricity will shift over the next 25 years. Virginia's current reliance on coal is caught in a political battle over air pollution vs. cheap energy.

Pollution controls on ozone, particulates, and greenhouse gases have increased the cost of coal-generated electricity for Virginia customers. Since the Clean Air Act was amended in 1990, Virginia utilities have delayed replacing old coal-fired power plants built after World War Two. Utilities used a provision in the Clean Air Act to allow for "repairs" at old plants to perpetuate grandfathered levels of air pollution exceeding current standards.

CSX coal train on McClure River in Dickenson County, hauling coal on century-old Clinchfield Railroad route from Kentucky to South Carolina

For economic as much as environmental reasons, the inefficient and small coal-fired plants at Possum Point, Bremo Bluff, Alexandria, Glen Lynn, and Chesapeake finally were converted to different sources of fuel or shut down. Utilities are no longer building new coal-fired power plants such as the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center. If the site for the proposed Cypress Creek Power Station site is developed for electrical generation, any new power plant there may be fueled by wood waste.3

Baseload electrical generation facilities, the power plants that run all the time, are being located further from urban areas. That helps utilities and merchant power producers to cope with air quality attainment standards, and to minimize land use conflicts with suburban neighbors. As a result, the highly-centralized system for distributing electricity from a few generating sites to 8 million residents throughout the state customers will have to be maintained.

More transmission lines will be constructed through both developed and undeveloped areas, creating more conflicts over land use. The Potomac Appalachian Transmission Highline (PATH) project was dropped after the Piedmont Environmental Council and others demonstrated that the projected growth in electricity demand by utilities was not valid, but other power lines are still planned by the utilities.4

modern powerlines at Flowerdew Hundred, crossing the James River at approximate location of early colonial windmill

Utilities in Virginia are building solar farms because they produce inexpensive electricity, not because of government mandates. Virginia has no mandatory requirement for utilities to increase their generation of electricity from renewable sources. There is a voluntary renewable portfolio standard (RPS). The RPS 2025 target is to generate 15% of electricity from renewable resources.

In the "fine print," the Virginia target is for investor-owned utilities only. The voluntary standard excludes electric cooperatives, municipalities, and industrial co-generators. The baseline for calculating the 15% also excludes 2007 sales attributable to nuclear generation; the target is significantly lower than 15% of "all electricity in 2025."5

Even if the Federal and state governments commit to renewable resources for generating a significant percentage of energy, the centralized production/decentralized distribution model will continue. Biodiesel plants might replace foreign oil fields, but cars might still fuel up at gas stations. Sources of electricity might become wind farms off the coast of Virginia Beach or biomass burners/solar farms that replace coal-fired power plants, but the massive network of powerlines will still be maintained.

Though the grid will always be maintained to ensure reliable delivery of electricity, distributed generation of electricity is still likely to expand. Solar cells that feed power into the grid, and batteries that store power from such cells, are getting cheaper every year. Solar cells are now cost-effective for many homeowners, independent of government subsidies.

Under net metering, residential customers with photo-voltaic (PV) solar cells on their roof can offset the cost of their electricity purchases from the utility during a billing cycle. Current Virginia regulations do not allow customers to produce more electricity than they use and sell the excess to the utility, but regulations can change. If the public adopts solar cells as a standard item on new houses, then political pressure will grow to require utilities to purchase excess electricity generated at a residence.

The alternative to selling surplus electricity is for homeowners with excess capacity to purchase electric cars, so extra electricity generated by solar cells can be used to charge the car. If battery-powered cars become common, then sunlight on millions of Virginia house roofs will cut into the dominant role of gasoline/diesel in the transportation sector.

The current distribution technology will have to get "smart" in order to manage the less-reliable renewable sources. Solar cells and wind turbines are intermitent producers, so the ability of grip operators to "dispatch" electricity to match demand with supply will become more challenging. Existing grid technology will be have to be upgraded to respond to signals from residential/office/industrial customers, and in some cases to transmit electricity generated by those customers from solar photovoltaic (PV) cells on many decentralized rooftops.

The installed network of power lines will remain forever, a visual eyesore that will provide backup power to all houses. If communities are built without a connection to the grid, they would resemble today's neighborhoods where powerlines are buried underground. If solar power becomes the prime source of energy for battery-based cars, then gas stations may become as rare as phone booths unless they morph into refueling stations offering recharges.

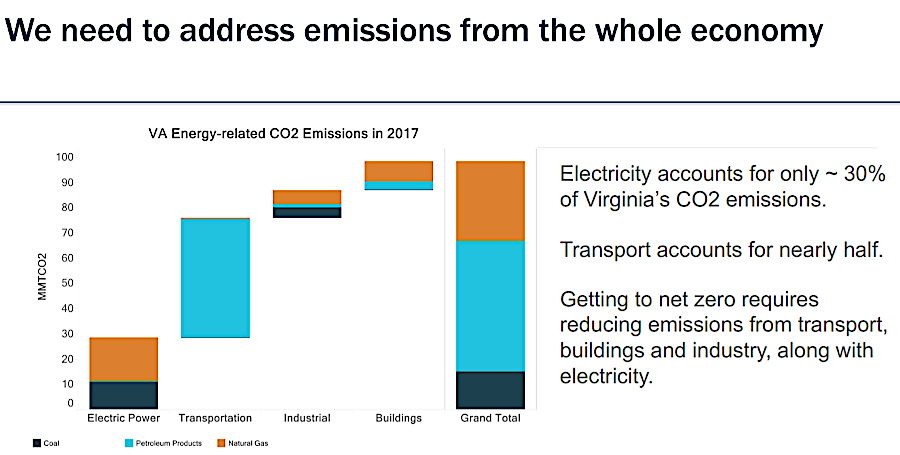

Getting Virginia to net zero carbon emissions will require altering more than just electricity generation. In 2021, about half of carbon emissions were produced by vehicles. Replacing vehicles powered by gasoline/diesel with electric vehicles, powered by carbon-free electricity, was a key step towards decarbonization.6

half of Virginia's carbon emissions were generated by the transportation sector in 2017

Source: University of Virginia, Decarbonizing Virginia's Economy: Pathways to 2050

mill races carried water from the James River and Kanawha Canal to power equipment at the Tredegar Iron Works

Source: Library of Congress, Illustrated atlas of the city of Richmond, VA (1877)