Virginia's caves developed initially in calcium-rich bedrock below the water table

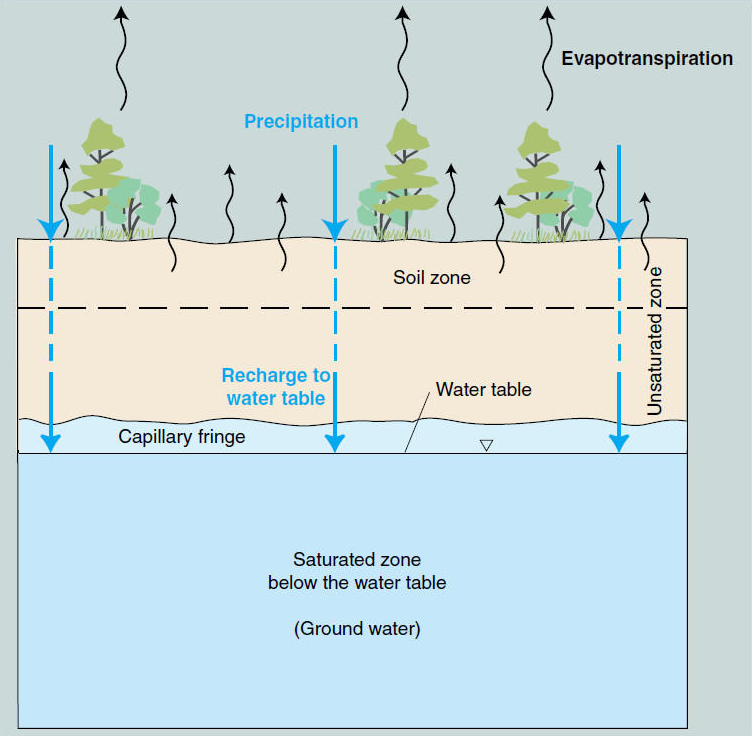

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Groundwater is the area underground where openings are full of water

When the groundwater emerges back at the earth's surface at the top of the water table, it's known as a spring. Most are gentle seeps at the headwaters or edges of the many creeks in Virginia, but in some larger springs you can see water literally bubbling up from underground.

In limestone areas, springs are caves-in-process. Once the ground water drops, those underground passageways carrying water to the spring will be filled with air... in other words, a cave. Today there may be a small pipe in a hillside near a road where tourists can fill a jug with "mineral water." Come back in a few thousand years, however, and you might find a sign at the same location advertising cave tours, where some calcium-enriched groundwater will have created speleothems (stalactites hanging from the cave roof, stalagmites on the cave floor, flowstone on the cave walls, etc.).

Very few springs develop into caves in Virginia. Springs are common in the Blue Ridge, the Piedmont, the Coastal Plain, and in the Appalachian Plateau where caves are uncommon. In those physiographic provinces of Virginia, groundwater will dissolve minerals too, must typically the resulting tiny voids underground will be filled by other grains of quartz, feldspar, or other minerals.

In the Valley and Ridge physiographic province, groundwater can dissolve enough of a limestone formation to create a ubstantial cavity. These underground spaces evolve in the zone saturated with groundwater, below the water table.

Virginia's caves developed initially in calcium-rich bedrock below the water table

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Groundwater is the area underground where openings are full of water

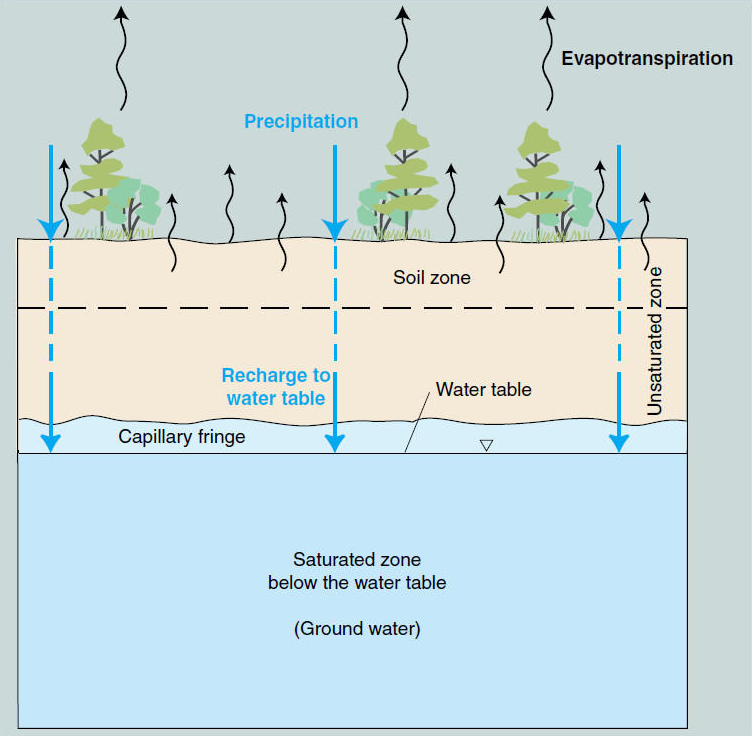

In limestone country, the surrounding rock will support the weight of the overlying sediments and allow the voids to grow into the large rooms visible today on commercial cave tours. In other cases, the dissolving bedrock will cause the surface to slump, creaking sinkholes where rainwater drains into the ground rather than flows across the surface to a creek.

bedrock dissolving below the surface can creake sinkholes

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Cover-subsidence type of sinkholes

The location and shape of cave passages and rooms reflect the geology of a particular site. The water underground flows gradually to the spring, and it follows the lines of least resistance. In all the upheavals forming the Virginia landscape, the limestone has been cracked in places - and the water will follow those weak spots until it reaches the surface. The calcium carbonate dissolves fastest where the water is flowing and where the crumbled rock surface is exposed to chemical action.

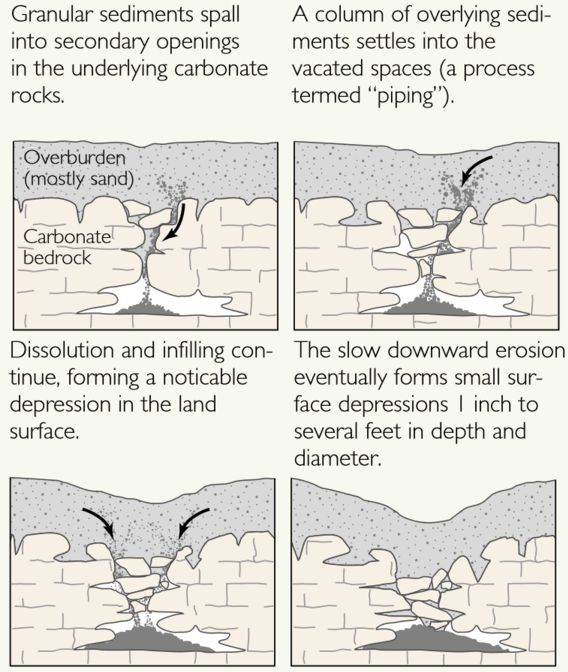

in karst landscapes, rains seeps underground and sinkholes (brown lines) form rather than surface streams

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Virginia Natural Heritage Data Explorer

The initial, tiny water channels underground grow and grow over time. When the erosion on the surface cuts down to intersect the underground conduit, the result is a large spring. Erosion will continue to cut the earth's surface even lower - remember, the Appalachians may have been 20-25,000' high at one time, and the Coastal Plain shows how much has eroded in 225 million years. When the surface level drops, the groundwater will drop and emerge to the surface at a lower elevation, leaving the old spring high and dry. The spring where the water used to emerge will become a cave entrance, and the old passages in the water-filled conduit will become cave rooms.

In many cases, however, the roof of the cave will collapse as the water level drops and the ground dries out. Some of the old ceiling of a cave may exist for a brief period of time as a "natural bridge," before the entire roof collapses. Sometimes a wall of the cave will remain, as at Natural Chimneys, before it too erodes away.

A rubble-filled path in the ground may be all that marks the old route of the water leading to the spring. That path may erode faster than adjacent limestone, creating a small valley. That wrinkle in the surface topography may be all that humans ever see of the conduits leading to a former spring - even in limestone areas, few springs will grow into caves large enough for people to visit.

In Florida, there is little topographic relief and the caves are still filled with water. Divers at the large Florida springs are now exploring the water-filled caves, using scuba gear to seeing the rooms and passages. Most Florida bedrock has not been uplifted high enough above the level of groundwater to have air-filled passages, and Florida Caverns State Park offers the only commercial cave tours in the state. (As the springs discharge dissolved bedrock, Florida loses about 3 feet of elevation every 38,000 years to "underground erosion."1

Sections of some Virginia caves are still filled with water too, because the water table has not dropped completely below that section of rock which dissolved underground over thousands of years. Divers who take the risk of pushing past the water-filled sumps in Virginia caves may rise up into other passages and rooms filled with air. In addition to overcoming the technical challenges of diving in a narrow cave passage, and facing the thrill of danger (cave diving is far from a safe activity...), cave diving offers a unique thrill of discovery. The portion of the cave on the other side of the water-filled passage is likely to be a pristine wilderness area, never seen before by any other human. Ever. There are no other places in Virginia where you can make a credible claim that you are the very first to see it.

The limestone bedrock west of the Blue Ridge was formed 500 million or so years ago, long before the Appalachians were uplifted, but the caves in the limestone may have been created only in the last few thousand or million years. In geologic time, caves are relatively new. However, even "new" caves with deep layers of sterile silt and mud, washed in over the years, may harbor evidence of previous visitors, including both animals and early Americans over the last 10,000 or so years.

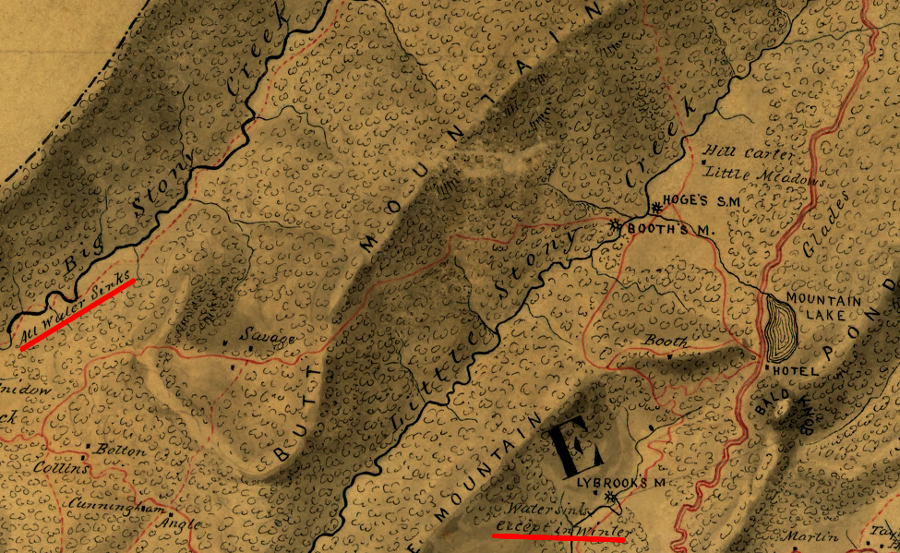

Civil War maps recorded sinking creeks in limestone valleys near Mountain Lake in Giles County - but the lake itself is not on limestone, so its fluctuations have a different geological cause

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Craig, Giles, Montgomery and Pulaski counties, Va. (1864)