measured by the number of acres used to grow any agricultural species, hay is the #1 crop in Virginia

measured by the number of acres used to grow any agricultural species, hay is the #1 crop in Virginia

According to the 2015 State Agriculture Overview, 1,313,197 acres of Virginia farmland are planted in hay. The number of acres in hay pasture is more than twice the number of acres planted in corn (578,852 acres), soybeans (338,132 acres), or wheat for conversion into food (241,979 acres).1

hayfields provide classic vistas and open space in rural Virginia

Most Virginia hayfields grow a variety of perennial grasses, including fescue, orchard grass, timothy, plus clover and other "forbs." Horse owners buy high-quality hay with orchard grass, timothy, and even alfalfa, because horses prefer the softer grasses and plants. Horse owners prefer to purchase the second cutting of hay in a season, because the first cutting may include harder stems.2

Hay is harvested in the summer and used to feed cattle and horses in the winter, when grass goes dormant and grazing opportunities outdoors are limited.

grass regrows in the summer, but during the winter supplemental feeding from stockpiles of hay is required on most Virginia farms raising cattle, horses, and other grazing animals

Hay requires far less work to plant, weed, and harvest. A part-time farmer has little spare time, if he or she is working in a day job to ensure the family gets a steady income no matter what the weather, health benefits, and an employer match to a 401K retirement fund.

A farmer may be able to make more profit by dividing fields with fences and rotating livestock between pastures rather than growing hay. Having animals eat the grass is more efficient than harvesting hay, storing it, then feeding it to livestock. However, fencing and watering systems for each field require extra up-front capital investments, and moving animals requires extra time.3

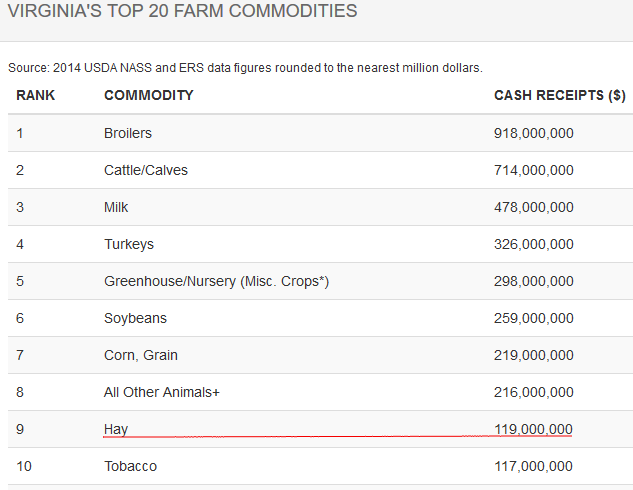

hay is the #1 crop when measured by acreage in Virginia, but the value of hay is less than value of other crops

Source: Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Virginia's Top 20 Farm Commodities

Growing hay and raising a few beef cattle is far easier than growing row crops such as corn, soybeans, and wheat. Those crops must be replanted each year, but the perennial grasses and clovers in hayfields will regrow on their own each spring.

The species in hayfields grow from the bottom just like grasses in the front yards of suburban homes. Cutting the top of the plants in a hayfield will not kill those plants. Part of the skill in managing a pasture is knowing how much grazing will stimulate new growth, and when to move the animals to another pasture. Hayfields are easier to manage - when the grasses are mature and produce seeds, then it is time to harvest.

wheat requires far more up-front investment and labor to grow compared to hay

Hay requires little machinery; farmers do not need big tractors to plow/seed/fertilize, so hay is cheaper to grow than other crops. The costs of "inputs" (seed, fertilizer, herbicides and pesticides) for hay are far lower. Little time is required to grow hay, other than the harvesting.

Ranchers raising livestock may choose to graze animals in a pasture as the grass grows in the summer. That grass will be harvested directly by the animals and will not reach maturity. Hayfields, in contrast, will have tall grass that develops seeds before being cut and baled for later use.

at Joel Salatin's Polyface Farm in Augusta County, pastures are grazed by cattle and then poultry feeds on the bugs attracted by the cattle dung

When the hay is ripe, farmers check the weather report to find a predicted few days without rain. Using tractors that are essentially large lawn mowers, they cut the hay and then let the sun dry the stalks of cut grass lying in the fields.

solar energy dries hay before it is baled

farmers use hay stockpiles to feed livestock in the winter, when grass does not grow in the fields

Source: Library of Congress, Untitled photo, possibly related to: Farm near Warrenton, Virginia (by Marion Post Wolcott, February 1940)

Hay used to be stacked in the fields until it was fed to livestock. Today, modern equipment is used to bale the hay and move it to a barn or edge of the field.

haystacks, with corn shocks in background

Source: Library of Congress, Haystacks and shocks of corn in field near Marion, Virginia (by Marion Post Wolcott, May 1941)

Once the hay dries to the desired level of moisture, the farmer bales it. If hay is baled immediately after cutting, the moisture in the grass will cause it to mold or ferment, making it inedible for cattle and horses. The heat of fermentation can even cause hay bales to burst into flame spontaneously.4

before cutting hay, farmers wait for forcasts predicting several days of sunny weather

Bales are often wrapped in plastic and stored out in the fields until needed to feed livestock. The outside edge of a hay bale may be damaged by weather, but the interior of the bale will stay suitable for animal food. Outdoor storage has reduced the costs of building and maintaining hay barns, so the rural landscape is now dotted with patches of plastic and the classic wooden barns are slowly disappearing.

after drying to the right moisture level, hay is wrapped in round bales and stored outdoors until needed

hay has been stored in barns and kept overwinter in the fields in haystacks

Source: Library of Congress, Barn with hayloft. Louisa County, Virginia and Farm scene. Louisa County, Virginia (by John Vachon, 1939)

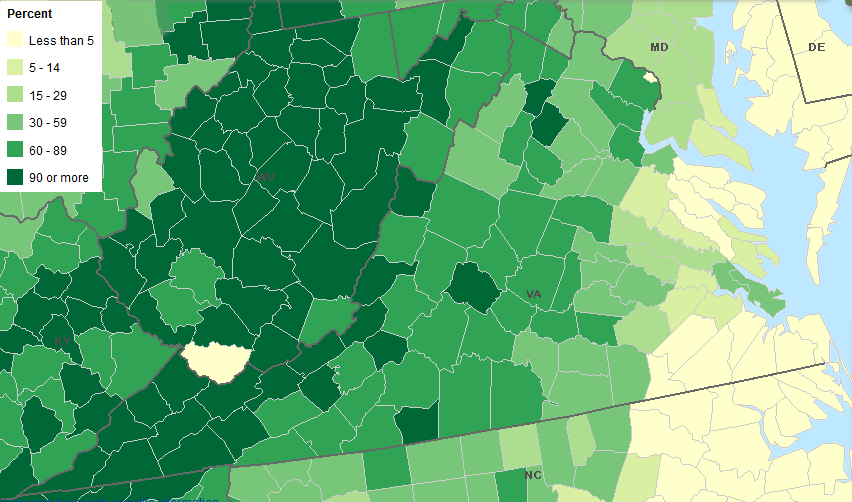

in the hilly topography of Southwestern Virginia, farmers use a higher percentage of acres for growing hay than row crops such as corn and soybeans

Source: United States Department of Agriculture, Ag Census Web Maps, Acres of Forage Harvested - Land Used for All Hay and All Haylage, Grass Silage, and Greenchop as Percent of Harvested Cropland Acreage: 2012

hayfield near Gratton in Tazewell County

deer prefer to browse on twigs at the edge of the field rather than eat grass, so they do not compete for hay with domesticated livestock