John Smith negotiating for corn

Source: National Park Service, Sidney King Paintings

John Smith negotiating for corn

Source: National Park Service, Sidney King Paintings

Corn (Zea mays) evolved in Mexico. The grain was unknown in Europe until after Columbus crossed the Atlantic Ocean.

When the English settlers arrived at Jamestown in 1607, corn was a key food crop of the Native Americans in Virginia. The English colonists planned to trade for food (as did the Spanish in Florida), and exchanged copper and other manufactured items for food. From the beginning, the colonists were planning to eat corn grown by the Native Americans in Virginia.

John Smith and others in Jamestown discovered that Powhatan was a canny negotiator who recognized the value of his corn and maximized the price. The English defeated his "paramount confederacy" in three Anglo-Powhatan wars, in large part because the English captured the stored corn in the Native American towns and cut down the growing crops in the fields. (As colonial settlements expanded, tobacco was often planted as the replacement crop.)

experimental corn plots at Virginia Tech's Kentland Farm

(Montgomery County, with Radford Army Ammunition Plant in background across New River)

The Virginia natives may have domesticated squash, sunflower, sumpweed, and goosefoot, converting wild species into crops that could be farmed regularly - but corn was imported, not domesticated in Virginia. Native Americans in Virginia, including the Chickahominy tribe ("coarse ground corn people") relied upon a food source that was domesticated originally in Mexico close to 18° of latitude.

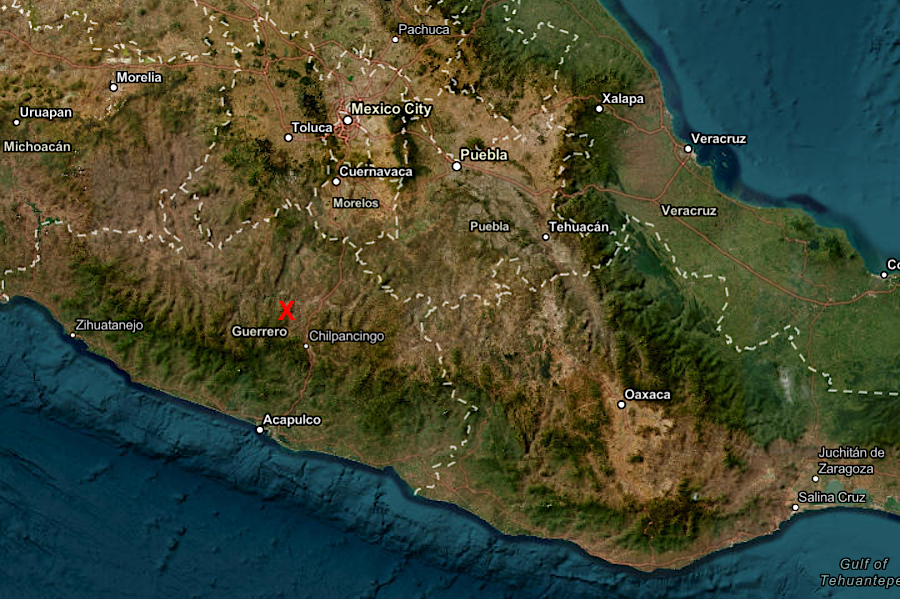

Corn was originally a crop that grew in the tropics, halfway between Virginia and the Equator. The original teosinte has only 12 hard kernels on each head of grass, in contrast to the 1,000 soft kernels on a modern corn cob. A lowland subspecies of teosinte, Zea mays parviglumis was first domesticated about 9,000 years ago in the Balsas River Basin, located in what today is now the state of Guerrero. It spread from its origin at 18° north of the Equator along the Pacific Coast to Peru and Bolivia, at a similar latitude south of the Equator.

Zea mays parviglumis was domesticated 9,000 years ago in the Balsas River Basin (red X), then hybridized 4,000 years later with Zea mays mexicana from the central highlands

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Around 6,000 years ago, the plant was brought into the highlands of central Mexico. Zea mays parviglumis hybridized there with an upland subspecies, Zea mays mexicana. 15%-25% of the genes in modern corn still come from the subspecies adapted to the cooler temperatures and shorter growing season in the highlands.

At roughly the same time hybridization occurred, the foragers who originally domesticated corn adopted a more sedentary lifestyle and became more dependent upon agriculture. They spread the hybridized corn into new areas.

By 4,000 years ago, corn was growing as far north as 30° latitude. Over time, new variants were developed which could reach maturity up to 45° latitude and even into southern Canada. At those higher latitudes, germination came later and the growing season was shorter. Even today after dramatic genetic modification, corn requires a minimum temperature of 50°F to germinate.

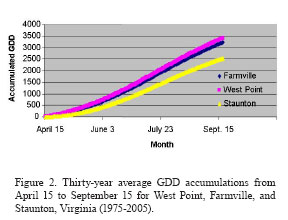

growing degree days in West Point (Coastal Plain), Farmville (Piedmont), and Staunton (Valley and Ridge)

Source: Virginia Tech, Using the Virginia Cooperative Extension Climate Analysis Web Tool to Monitor, Predict, and Manage Corn Development

Within Mexico, 59 varieties of native corn are still grown. One strain that has been produced for 4,000 years, nal t'eel, has survived the recent expansion of American hybrids across Mexican farmland in part because of whisky makers. Distillers are using nal t'eel to create a unique flavor that is distinct from bourbons produced in Kentucky.

The English colonists who reached North Carolina in the 1580's discovered Native Americans planting flint corn to create three crops per season. The kernels were round and did not have the "dent" seen in the white/yellow corn so common today.

Modern Thanksgiving decorations often include "Indian corn." It is distinctive because the kernels are not all yellow. Thomas Hariot described the primary food product grown by Native Americans in 1590:2

flint corn grown by the Native Americans had multicolored kernels without the dent in modern corn

Source: Indian Corn (by RichardBH) and PxHere

According to John Smith, the Algonquians he met were committed to agriculture, and corn (which he also called "wheate") was their primary crop:3

The Algonquians relied upon corn for 50% of their food supply, growing 20 bushels/acre of corn. Annual use was roughly 15 bushels/person, but this did not last throughout the year. The English believed the supply of dried kernels would be exhausted before the new crops could be harvested, though the elite of the Powhatan culture (priests and chiefs) would have access to stockpiles that were not available to the commoners.4

Corn grown by the Native Americans in Virginia was a major food source for the English colonists, as well as the Native Americans. Powhatan controlled access to food as a key part of his foreign policy with the English. To bypass his control, the English extended their explorations beyond his territory, starting with John Smith's explorations of the Chesapeake Bay and Potomac River in 1608.

In 1613, Pocahontas was captured by Captain Samuel Argall as he negotiated for food supplies with the Patawomeck tribe at the mouth of Aquia Creek. Of course, the English also used food as a weapon in the Anglo-Powhatan wars. They seized mature corn and destroyed immature crops in Native American towns, denying food to their enemies.

As the English settled Tidewater, then the Piedmont and west of the Blue Ridge, they planted more fields of corn. To convert the kernels into corn meal, the colonists built grist mills with stone wheels that ground the grain. Most Virginia mills were powered by water in local streams. Corn was ground for local consumption, while wheat was exported to the Caribbean, Europe, and other markets.

In 1702, Frantz Ludwig Michel visited Virginia from Switzerland. He described how corn was grown by the colonists:5

colonial-era exhibit at Williamsburg shows wide spacing between rows, while modern corn rows are planted in rows 30" apart

harvesting corn in the Shenandoah Valley, 1941

Source: Library of Congress, Scenes of the northern Shenandoah Valley, including the Resettlement Administration's Shenandoah Homesteads (by Ben Shahn, 1941)

cornshocks in farm fields

Source: Library of Congress, Cornshocks in the fertile Shenandoah Valley, Virginia (by Marion Post Wolcott, November 1940) and Cornshocks and fences on farm near Marion, Virginia (by Marion Post Wolcott, October 1940)

Today, corn in Virginia is grown for livestock as well as human consumption.

In 2011, Virginia farmers planted 490,000 acres of corn, including corn intended to be used as silage (with stalks and ears harvested together, fermented, and used as winter food for livestock consumption). 340,000 acres were harvested for grain, most of which ended up as livestock food, and 130,000 acres were harvested for silage. Statistics are not perfect, but it is possible that farmers decided 20,000 acres of corn fields were not growing successfully and chose to plant another crop rather than wait for their corn to mature.6

A "Corn Belt" was well-defined by 1850

Source: Baker, O. E., A Graphic Summary of American Agriculture, Based Largely on the Census of 1920,

Publication 878, separate from Yearbook of the Department of Agriculture, 1921, p. 10, Government Printing Office, 1922

In 2022, 25% of farmland in the United States was planted in corn. There were almost 200 facilities stretching from South Dakota to Indiana converting corn into ethanol for use as a fuel, such as 10% of E10 gasoline. Federal subsidies are key to the conversion of corn into a substitute for gasoline, since more energy is required in planting/harvesting/processing/transporting the ethanol than it delivers inside an internal combustion engine.7

Biofuels offer increased potential for corn production in Virginia. However, the largest biofuels plant, in Hopewell, was designed to process primarily barley. A plant proposed for the City of Chesapeake, to produce ethanol from corn, was blocked by a local decision in 2007.8

Potential impacts on the Chesapeake Bay are major concerns with raising more corn for fuel. Corn requires fertilizer, and runoff from agriculture is a major source of the excess nutrients that are damaging the bay.

Modern corn varieties include genetically-modified varieties with resistance to disease and insects. Most corn in Virginia is grown without irrigation, and water stress during droughts can affect yields substantially. Corn plants typically produce 15 leaves and one ear. Emergence is categorized as VE stage, first ear is V1 stage, and 15th ear is V15 stage. Length of the ear is determined primarily in the V7-V12 stages, and length of the stalk is most sensitive to environmental conditions during V9 and V10 growth stages.

modern corn harvesters come in small as well as large sizes

Corn plants start to grow when temperatures reach 50°F and grow faster until temperatures reach 86°F. Farmers calculate growing degree days (GDD) or "heat units" to evaluate status of their crop. If the plants are not growing as expected, then that is a clue that additional fertilizer or other management action might be appropriate.9

Pollen is shed from the male flowers of a corn plant and distributed by wind and gravity. If a pollen grain lands in the right place and fertilizes the female component, one kernel of corn will grow on an ear. Many successful pollen grains are required to produce the full set of kernels on a single ear of corn. Each single pollen grain has to fertilize the egg within each future kernel.

First, a pollen grain needs to land on the tip of a strand of corn "silk" that is attached to what will become the kernel. Silks are receptive for about five days. If pollen ripens and then drops during excessive heat or storm when the silks are ready, fertilization may not occur. In that case, a farmer will end up with fewer bushels per acre.

corn pollen is produced in male flowers (red circle) and, after landing on a silk thread, grows a tube down to fertilize the egg

Source: US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Corn grows on Goldpetal Farms in Chaptico, Md

A pollen grain that lands on a receptive silk will grow a tube through the silk all the way down to the egg nucleus within the future kernel, which is next to the corn cob. That growth can require 12-24 hours. Two cells with male nuclei then migrate down the pollen tube inside the silk. One cell fertilizes the egg which ends up producing the seed. The other male nucleus fertilizes two nuclei that grow the starch which surrounds the seed and forms the bulk of the kernel.

After fertilization, silks dry up. People who eat corn on the cob peel the husk and then the dried silk away from the starch-filled kernels that contain the seed.10

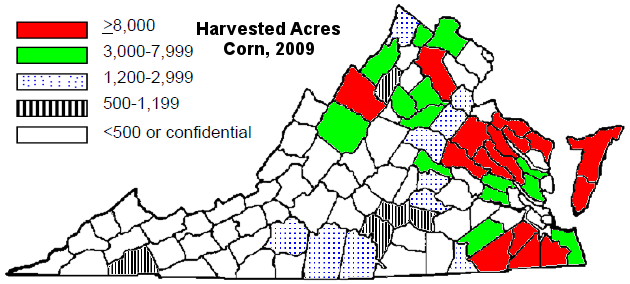

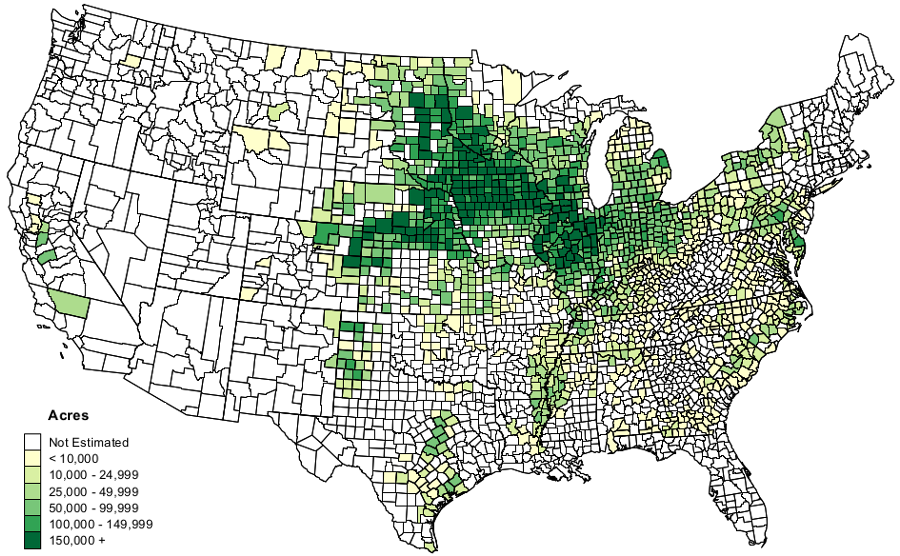

in 2009, corn production in Virginia was concentrated on the Coastal Plain, the northern Piedmont, and the Shenandoah Valley west of Massanutten Mountain

Source: USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service, Corn and Soybean Distribution Maps

Fig. 24. "Over two-thirds of the corn acreage of the world is in the United States, nearly all east of the line of 8 inches mean summer rainfall and south of the line of 66° mean summer temperature. Nearly 90 per cent of the acreage of corn for grain in the United States is in the Corn Belt, the Corn and Winter Wheat Region, and the Cotton Belt. In these three regions corn constitutes about one-third of the acreage of all crops. In the Corn Belt it is dominant, contributing nearly two-fifths of the acreage and half of the value of all crops. Hay, associated with spring oats in the northern portion and with winter wheat in the southern portion, are the other important crops in the Corn Belt."

Source: Baker, O. E., A Graphic Summary of American Agriculture, Based Largely on the Census of 1920

Virginia imports corn grown in the Midwest to feed chickens and turkeys

Source: US Department of Agriculture, Corn - Planted Acreage by County

many Piedmont farmers raise corn

rolling hills in Fauquier County support pasture and corn for raising horses